Avengers Arena is unfair. From the initial announcement of this book, it had everything going against it. We were going to lose one of the very few strong teen books to make way for an obvious cash grab for the Hunger Games scene and, by age discrimination alone, force young heroes to hunt and kill one another. Raise your hand if you were hoping to just get a new Runaways book? These are some fan-favorite characters here, seen in drips and drabs, and when they finally get some on-panel time, we find they're nothing more than targets in an absurd trap set by villainous joke Arcade. Arcade! Their lives were in peril thanks to low-rent Elton John with a Rube Goldberg fetish!

But the worst sin of Avengers Arena is that it's actually really good.

Yeah, I am absolutely serious. Avengers Arena has surprising potential, and it has introduced some interesting characters and developments that keep me grudgingly coming back each issue. It's hard to admit that, considering how much I really wanted to hate this book, based on little more than its Battle Royale cover. Despite the calm, honest words of Avengers Academy writer Christos Gage when he asked readers to give the new book a chance, the whole premise turned me off. When the first issue of Avengers Arena came out and we lost our first teen hero, that death proved how right I was. Why trust a book that's just going to kill everything you love? And why kids?

It seems unnecessarily cruel to put together an ongoing series promoted to us as sensationally as possible. Don't get too attached to anyone! Kids will die! They might even kill each other! The shock value of teens in terror can pull the reader right out of the narrative and forces us to look at the value of the story line than just enjoying the ride. Kids have to be killed for a reason, not just as scare tactics and and cheap heat.

So why does the death of children hit us harder than your usual comic book demise? Why is the loss of a child's life so difficult to bear in the super-heroic medium? And why in heaven's name do I keep reading Avengers Arena?

Children and comics are practically peanut butter and jelly; kids love to read them, we love to see them fight crime. Kids are adventurous, have less responsibly to jobs and security, see the world with a wonder that can set the tone for the reader and give us someone we can all relate to. After all, while we're not mutants or cosmically radioactive, we've all been or are kids at one point, right? U.S. culture has venerated youth -- from TV to movies to music, teens are traditionally cutting edge. And of course, seeing someone like yourself in the pages of a comic can generate an audience and tap into a demographic. Strong female characters theoretically bring strong female readers. On a less cutthroat note, children in comics can represent potential, the future and hope.

Which is why we kill them. The more childlike they look or act, the more shocking it is when they're murdered. These deaths affect the reader just as much as all of the points mentioned above can lure the reader in. It's a loss of innocence and can challenge the reader's values of life and death.

Getting back to the cutthroat points, killing a kid can spur the surrounding characters into action just as much as finding a supporting female character stuffed in a refrigerator can, no matter if the action is revenge or change or simple despair. All of this will result in a much more dramatic story if done correctly. If not, everyone will call you on it; if there's one thing comic fans like less than change, it's being emotionally manipulated.

There's just a wide range of ways to get this wrong, why would writers keep coming back to the dead kid well? Back in the days of Bucky Barnes, Stan Lee originally thought teen sidekicks were reckless and irresponsible for adult heroes to have along, and I can't say I disagree. Our heroes are here to protect us, and to let the innocent fall makes the whole thing seem a sham. On the other hand, if no child suffered then there's inconsistency to pull us out of the story; we're going to notice if the children in the story become Teflon. How do you manage this tightrope-like balance?

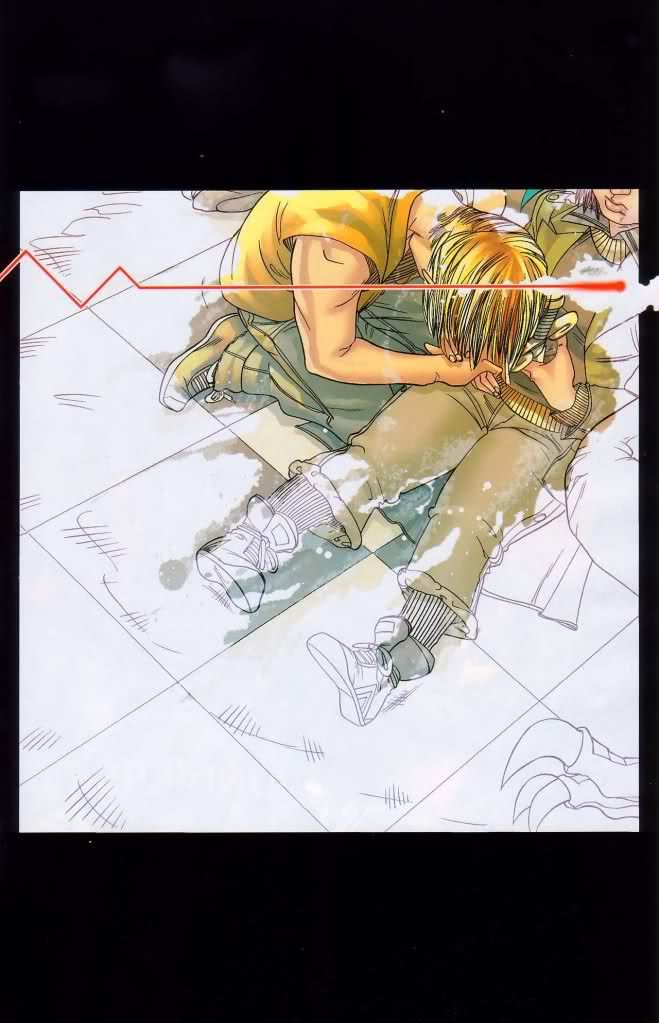

It's managed best with bravery. Let's face it, rarely are our heroes actively sending children to the front lines; more often than not, it's kids (super-powered or not) jumping into danger. In Avengers Arena #1, Mettle puts himself on the line to save Hazmat and dies quickly; on one hand, the death is used for shock value, but contextually, Mettle died to save the girl he loved, a brave act. As adults, we may have reservations on the threat of death for children, but kids won't see it the same way. In Runaways, Gertie Yorkes technically dies twice, once as a version from the future to warn her friends about an oncoming villain, the second time as her present self while rescuing Molly from the Pride and saving Chase from a killing blow. From the time the kids ran away from their supervillanous parents, they knew they would be hunted and stopped at any costs, and yet the took the chance and their lives into their own hands. Bravery in adversity makes heroes out of all of us.

The basic premise of Avengers Arena feels cheap. Without context and depth, it's a concept that lessens what our teen heroes have already gone through and cheapens what they've made of their lives and how much we've gone through watching them from issue to issue. But writer Dennis Hopeless seems to know that and is taking particular care to show these teen heroes as human, with small moments of emotion and frailty before letting them show their strengths. Five issues in and we're learning more about those involved then we are in their demise. It's not the deaths that truly matter, it's what they do about it and how they persevere through them.

All we ask as that these deaths not be in vain, but for heroism and the triumph of good storytelling.