THE COLOR BARRIER is a "magazine" spotlighting discussions on diversity in comic books, graphic novels and popular culture.

The interviews, profiles, and subject matter featured focuses on men and women whose accomplishments serve to create a more informative and culturally diverse landscape of entertainment.

THE COLOR BARRIER: Easton & Underwood on the Challenges of the Comics Industry

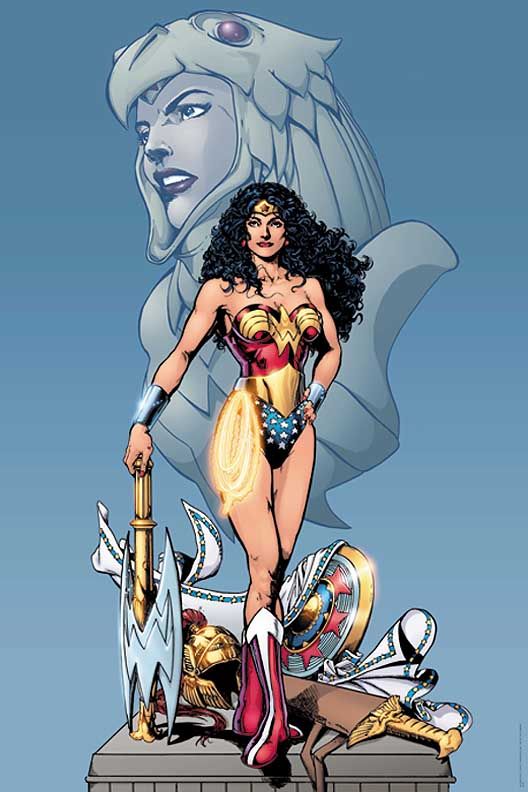

Phil Jimenez broke into the comic book industry as a penciller at DC Comics in 1991 and has been a fixture at both DC and Marvel ever since. His resume includes runs on "The Invisibles," "Tempest," "New X-Men," "Infinite Crisis," "Amazing Spider-Man," "Astonishing X-Men," "Adventure Comics" and most recently "Savage Wolverine." But he is perhaps best known for his work on "Wonder Woman," including a two-year stint as both writer and artist on the series that introduced Diana's first Black love interest, as well as co-authoring "The Essential Wonder Woman Encyclopedia" with John Wells. Jimenez publicly came out as gay during his work on DC's "Tempest," and much of his work has featured progressive storytelling and diverse characters.

Today Jimenez joins THE COLOR BARRIER for the first installment of a two-part discussion about Wonder Woman's sexual awakening on an island inhabited only by women, the stories he never had the chance to tell with the character and the secret origin of Diana's first interracial relationship. The writer/artist also reflects on the delicate issue of racial inequality when masked by the guise of progressive stories dealing with other issues.

In the PBS documentary "Superheroes: A Never Ending Battle," you spoke at length about DC Entertainment's Wonder Woman character. Anyone who's in the know in comics knows you're an expert on Diana.

Dealing with the quintessential Wonder Woman mythos, Diana grew up on an island of women until her early adult years. It occurred to me that DC Comics missed a great opportunity to explore the idea of Diana's first romantic love being a woman. Do you think Wonder Woman is an ideal character through which to examine love and sexual lifestyle?

Phil Jimenez: Yes. I think sex is part and parcel of Wonder Woman's creation. I think she and the Amazons were very much intended to explore all sorts of themes surrounding love and sex, sex and gender, and sex and power. The tragedy, of course, is that over the decades, this aspect of her character has been minimized considerably; it's been touched upon here and there, but now the character has been refocused into a goddess of war instead of a symbol of love. Again, there are commercial and historic reasons for this ("Seduction of the Innocent," anyone?) as well as creative ones but I agree with Mark Waid, who lamented (I'm paraphrasing) that by stripping the sex from Wonder Woman, you've stripped something really essential from her character, and really, the most interesting thing about her. Heck -- this is my argument for the "bathing suit" costume -- that costume is all about sex, sexual power, sexual defiance, body freedom and absence of shame. Of course it's not "practical;" no superhero costume is. It's a symbol of something else. Thus, the constant need to modify it, to make it battle-ready, to make it "practical" rather defeats the whole purpose of the original costume. This was, originally, a character that was full of fun and light; who saw crime fighting as an adventure; who had no shame about her body; who was a skilled enough athlete and fighter she'd never need armor in the first place (and while she used a sword here and there over her first few decades, it was rare with her, because really, with her power and speed, wouldn't that just be cheating? Where would the fun, and self-betterment be in that?).

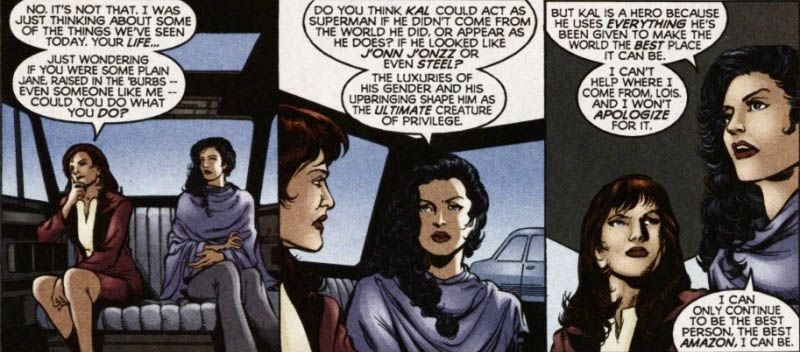

Without the sex, gender and love stuff in Wonder Woman, you're left with, essentially Xena-lite or the DC version of Lady Sif; a generic warrior maiden who doesn't represent all that much except strength through war, honor through violence, victory by the blade of a sword. Obviously, this imagery is powerful to some and incredibly effective in its way. It says a lot about how we feel about violence, war and its value. The shift also suggests something about what we think about sex, our comfort level with sex and sexual power, and a general, cultural sexism that suggests most things feminine are weak, and the way to really prove one's value (literally and figuratively) is shedding the feminine (especially if its sexual, but not sexualized) and embracing the masculine.

RELATED: Jimenez Enrolls in the Legion Academy

I've mentioned in other works that I believe Diana is the ultimate "queer" character -- meaning "queer" in its broadest sense -- defiantly anti-assimilationist, anti-establishment, boundary breaking. Looking back at the early works of the 1940s, sifting through all the weird stories and strange characters, you can find a pretty progressive character with some pretty thought provoking ideas about sex, sex roles, power, men and women, feminine power, loving submission, sublimating anger, dominance in sexual roles, role playing and the like. This stuff is far crazier and far more progressive than anything we've seen in "Wonder Woman" since. Later incarnations might have a more serious, "realistic" bent to them -- as "realistic" as a character born of the Greek gods can be. The genius in William Moulton Marston's work was taking a traditional myth, that of the Amazons, and totally upending it -- transforming it not into a warning about women but a celebration of them and their sexual and feminine power, transforming it into an entirely new myth by spinning it in an incredibly fanciful, progressive direction.

I've often wondered how I'd play Wonder Woman's first sexual experiences, especially on Paradise Island. My initial reticence has always been with the idea of Wonder Woman falling in love with any of the Amazons -- since they raised her, it was like an extended family of a thousand aunts, cousins, and sisters, as it were. The Amazons all knew Diana in such a familial way I wondered how their feelings for her could grow into something romantic. And Diana was young, compared to the other Amazons! I wondered if there wouldn't be a student/mentor angle to Diana's relationship with another Amazon; how even-planed their love could be, given the nature of their varied experiences (Diana was raised in isolated utopia, after all -- the only men in her life were the gods, which has to mess with one's head). And then, of course, there was her overprotective mother, Queen Hippolyta; can you imagine the Amazon brave enough to stand before the queen and declare her love for her daughter? Or can you imagine Diana bringing that Amazon to the palace and announcing her as her girlfriend?

Rethinking it years later, I absolutely can imagine such a thing. All of the above, actually! That stuff doesn't even feel like a hurdle anymore. What feels like a great obstacle, because of the brand Wonder Woman's become, are her typical love interests Superman and Steve Trevor. Any sort of relationship Diana might have with another Amazon ultimately seems doomed, because history tends to find her in the arms of one of these two men.

And then, of course, one must consider the exploration of romantic and sexual love in an enclosed, same sex society. How much of that attraction is genetic or natural? How much of it is exposure? How free were the Amazons sexually? How do the rules of sex and gender apply in a world closed to ours for 3,000 years -- so it's been allowed to develop in entirely different ways?

Regardless, I think Wonder Woman is the perfect character to examine love, sex, gender, and power. I wish there was more of that, and less of the war stuff. I'd rather see Diana become the goddess of love or the goddess of wisdom instead of the new goddess of war; I think the former roles suit her more, and cover far more provocative ground.

You are one of the few creators to both write and draw "Wonder Woman." Were there any themes or topics you wanted to write about, but didn't get a chance to tackle?

My initial goal during my Wonder Woman run was to "streamline" the character, taking the best bits (to my mind) of the previous runs and amalgamate them into a more cohesive vision of the post-Crisis Diana, with far more hints of her pre-Crisis counterpart added to the mix. But, as many know by now, I got the character in transition; during the first year of my run, I had three different editors on the book; the character was a part of two major crossovers which resulted in the death of her mother and the destruction of her homeland (two integral parts of my original pitch); 9/11 occurred during the middle of one of those events (and a crossover of my own); and I was reminded multiple times by the then EIC that I was simply the "fill-in" creator until the next one was ready to take over the book, which prevented any kind of long term plotting ( I think was scheduled to depart at least three times before I finally said enough). And that was just the first ten issues!

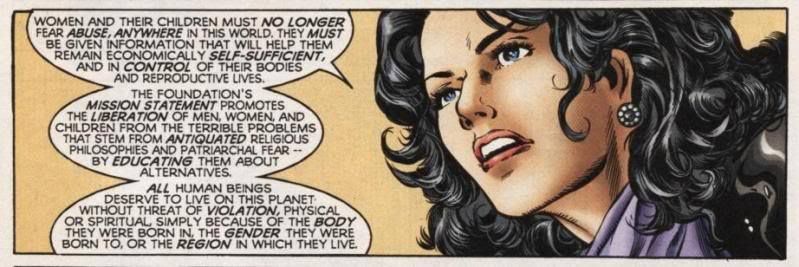

I was able to introduce a few ideas -- giving folks a taste of who Diana was as princess, ambassador, superhero, and woman; restructuring the political nature of Paradise Island (and ultimately transforming it into something far more interesting); getting to jigger with her villains, and crafting the "Day in the Life" issue I co-wrote with Joe Kelly -- one of the best comics I've ever produced, and one of the best working experiences I've had in comics (the story remains one of "the Greatest Wonder Woman Stories Ever Told" and a Top 10 WW issue in most lists, a fact of which I remain hugely proud).

RELATED: CCI: Phil Jimenez Spotlight

All of this is to say, I was able to tackle many things I wanted to in my run -- I just wasn't able to do it cleanly, without lots of changes and concessions and editorial intrusions (that "Joker's Last Laugh" crossover was nearly the straw that broke the camel's back). If I ever get to tackle the character again -- which I hope to do, since I have one or two last big stories to tell, tackling several iterations of Wonder Women -- I hope I have the opportunity to do so with some freedom and without the obstacles I faced the first time around. I think DC would get a Wonder Woman unlike any they've seen before... including my run from ten or eleven years ago.

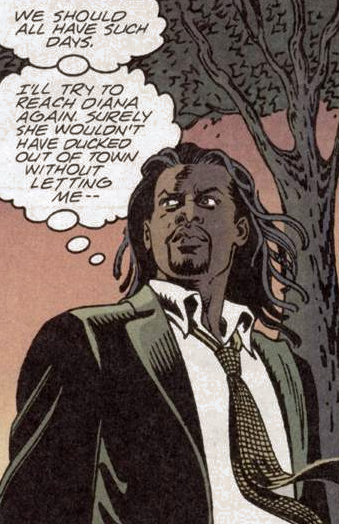

In your "Wonder Woman" run, you broke ground by creating a Black character as a romantic interest for Diana. Why did you make that decision, and what kind of feedback did you receive from the fans?

I made this decision for a couple of reasons. One, the character, Trevor Barnes, was an amalgam of two or three of my closest friends -- all black men, and all comic book fans -- and I wanted to create a character in the Wonder Woman universe that could represent them. And one of them is named Trevor, and I thought it was a nice play on the old "Steve Trevor" name, considering I'd planned him as a romantic interest for Diana.

I also wanted to introduce an African-American character from "Man's World" into the Wonder Woman universe. George Perez had done so in his early run -- Steve Trevor's superior, General Hillary -- and there were a few others since, but the most notable black character in the title had long been Phillipus, the Amazon captain of the Guard.

I'm of the belief that diverse characters have to be introduced, sometimes with quite a bit of zeal, onto consumers, who tend to be fairly conservative and attached to pretty specific iterations of their favorite characters. This is not always the case, but I find that diversity is only welcome as long as it's introduced by the hegemony in charge; that is to say, if a straight white guy does it, it's cool, and without agenda; if a creator of color, a female creator, or a gay creator introduces said diversity, it is often seen as full of agenda, and an obvious attempt at subversion. This is not always true, mind you, but I find it often is. It seems many readers are distrustful with sudden demographic shifts in their books, especially when it seems other, pre-established white characters might be shunted aside, and this situation was no different. (Ah, the sandbox of white privilege! You go play in your box with your own characters, because this one is ours!) Ultimately, my interest in introducing such diversity comes from two places: One, a desire to see my friends and the world I live in more properly represented in a medium I love, and two, the thousands upon thousands of new stories creators get when they have a diverse cast of characters and cultures to play with.

Reaction to Trevor Barnes was mixed at best, and hostile at worst. We got calls saying, "Get that Black monkey out of my 'Wonder Woman' comics" (Yes, seriously); and one fan reacted by saying he couldn't relate to Trevor like he could to Steve, because Steve was "blond and blue eyed like him." Many fans loathed the idea that Trevor might be the one to have sex with Diana (then, a virgin) before Steve himself did, even though the post-Crisis version of Steve was significantly older than Wonder Woman and married to another woman. Further, the fact that, in his first introduction, Trevor said "No" to Diana when she asked him out on a date made fans go ballistic, even though they had no idea why he said no (It was explained sometime later).

You and I, and Devin Grayson, had the pleasure of being speakers at Purdue University's Diversity in Comics Conference a year ago. The next day, the two of us had a discussion in which you made an astute observation about gay male interracial couples in mainstream comics.

In the cases of Archie Comics' Kevin Keller and Marvel Comics' Northstar from the X-Men, their Black husbands are the least "powerful" member of the couple, not on equal terms with their Caucasian partners.Do you think this is becoming a new archetype in mainstream comics, which displays racial inequality within the envelope of progressiveness?

I hope not -- that is to say, I hope it's not becoming a new archetype, a "perfect" representation of a particular type. I do believe these couples are intended to be progressive, certainly the Kevin Keller/Clay relationship, were incredibly progressive, considering the conservative nature of the medium (mainstream superhero comics and their ilk). I suspect the same is true, too, of the Northstar coupling -- while it's a bit of diversity upon diversity layered upon more diversity, I think it was born entirely of the best intentions of its creators, while creating material that a primarily White, straight male readership could still feel comfortable buying and collecting.

RELATED: Jimenez's "Wolverine" Savages the Poaching Trade

Ultimately, my hope is that, like all groundbreakers, these early, well-meaning couplings lead to all sorts of new permutations depicted in comic stories, and break free of the "super-powered white man straight-acting" lead, minority man powerless but appropriately loving husband-type you describe: same race, same sex couples; interracial couples where the white character is the powerless boyfriend/husband; couples where both gay leads are less "alpha" and perhaps a little less "straight-acting," for lack of a more evocative term; couples that defy typical heteronormative marriage molds and are involved in threesomes or open relationships, etc. And, of course, the gay playboy character, who may have more than one sexual or romantic partner. My guess is this will happen, but it will take time -- and initiative. I long for the day a mainstream superhero comic might feature two non-white gay characters as their leads, and see that book's sales soar.

One unfortunate side effect of the "straight to marriage" model of these kinds of relationships is that it sexually neuters them; it tidies them up, makes them safe and consumable for the masses. And no, I'm not disparaging those who choose to get married in real life; I'm suggesting that, in mainstream superhero comic book storytelling, gay marriage has had a way of compartmentalizing gay characters in a way that's romantic without being overly sexual. It's safe, and more easily digestible by most consumers (some of whom are gay) who still remain on edge about giving same-gender couples a sexual/romantic life that doesn't mirror the most traditionally upright models that many value for social and often political reasons.

I think another factor to consider here is heterosexism and misogyny. As long as there remain some very hard-edge parameters for gay characters to be "okay" -- white, muscle-bound, almost-straight except for their sex/romantic partners, I wonder how long -- if ever -- it will be before we start seeing this paradigm mixed up. The intersection of depictions of men and masculinity is a long and complex one, and, it seems to me, especially in minority communities. As long as there are "rules" for these characters to follow to be consumable, I wonder just how long it will take to break barriers down for truly diverse representation of same-sex couples in comics, and especially ones that feature minorities in one or both (or all) roles?

Stay tuned for the second part of Phil Jimenez' discussion with THE COLOR BARRIER tomorrow on CBR.