The chemical box was a podcast between Joey Aulisio and myself. It took us four years to record 25 episodes.

With that track record, we can't begin this column by promising anything, really. No set schedule. No overall mission. Joey and I just work in a way that's momentary, grabbing what we can when we can. The spontaneity is energetic, but admittedly it makes for limited workflow. You may get more of the chemical box here, in this form, but who's to say? You may never hear from us again.

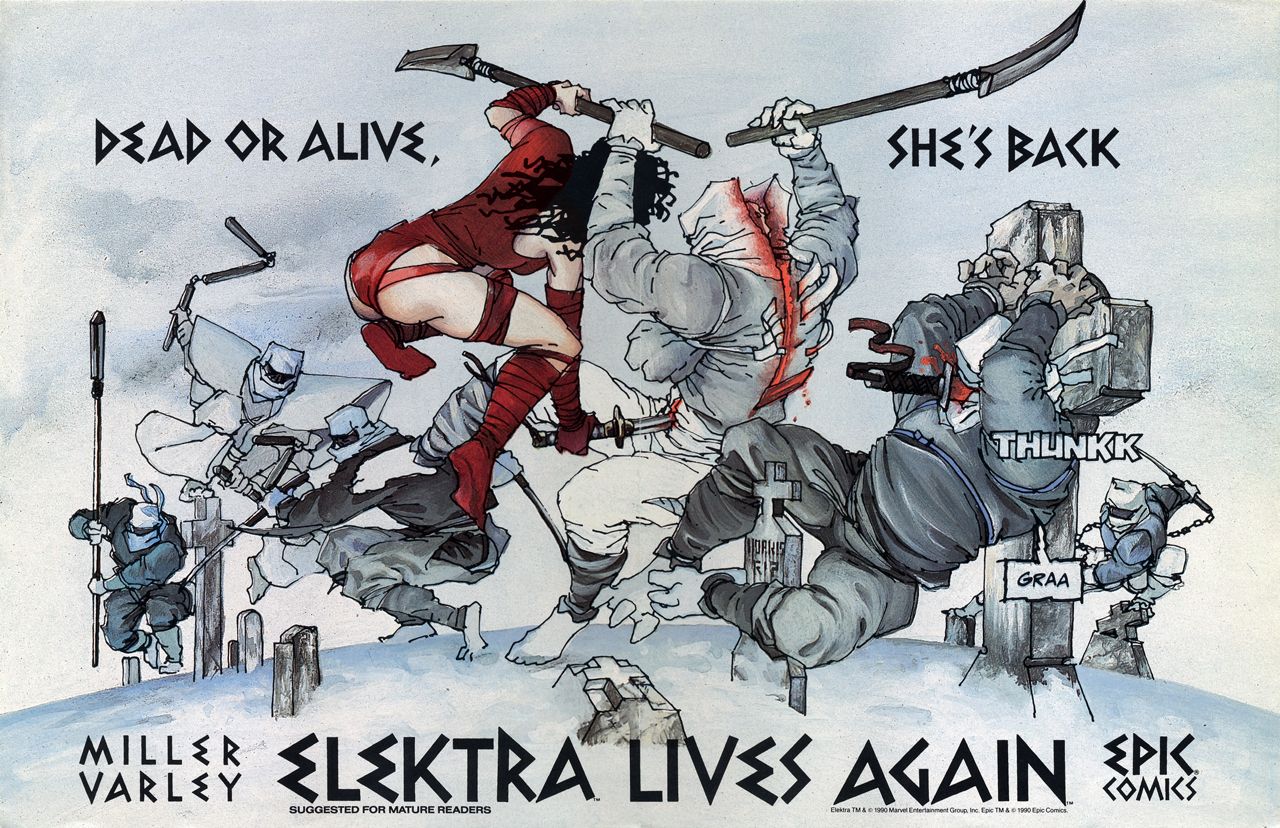

For now, just take the time and read these notes on Frank Miller's Elektra Lives Again, and see this as a singular piece of content produced because the time felt right.

---

Alec: So this is Frank Miller’s goodbye to Marvel, and for a time to superheroes. The genre with which he cut his teeth. Though elements of superhero fiction would follow Miller and grace his work past this departure, Elektra Lives Again makes it clear he’s ready to move on, presenting Matt Murdock as a seeming analog for the author, and as someone plagued by a lost love (a character Miller created). It reads very much like a letter sent to an old friend, years after the actual friendship, that intends to summarize (with some perspective) what happened between the two.

Granted, that’s a particular reading of this work, but it’s obvious, right? Elektra Lives Again tells its own story, and it can entertain a general reader browsing it by chance without any context of Frank Miller’s Daredevil, but if we’re going to read how we usually do, Joey, I assume this is our discussion. Maybe you don’t even see it this way?

There are details to this goodbye, though. Goodbyes are not simply about letting go, but coming to terms with the fact that what you are wishing good bye will carry on in your absence. Especially when it’s a character in a shared, corporate superhero universe (That’s where the title comes in!). This doesn’t sound like a farewell. It’s more like Miller is giving her away, saying it’s OK for someone else to interact with her because his time is up. After all, he kept her dead. Marvel wouldn’t let any other creator touch Elektra after Miller killed her. It has that in common with Animal Man. This metafictional touch in which the author confesses his absolute lack of power over his fiction.

Miller is possibly the guilty party. He could have left Elektra dead, but asked Bill Sienkiewicz to do Elektra: Assassin and kept the story going, forcing her importance on anyone who would read. When Elektra confronts Murdock with a similar conceit, that he is in fact “haunting” her, it feels true of Miller, too.

Elektra represents Miller’s time with superhero comics. She is his key, clear, tactile creation up until this point in his career with Marvel and DC. It’s arguable that he changed the genre these publishers publish by utilizing a particular tone/structure/pace previously unseen in this material, but Elektra is something Marvel can actually attribute a credit to. And that means something. Something Miller knew when making Elektra Lives Again. And that may be why he had to let her go. He needed to be removed of this elephant in order to do Hard Boiled, Sin City and Martha Washington. Because without her, he has nothing, and must start again.

I want to talk about the size of this book, and what’s actually on the page, but it felt right to start here, so to get it out of the way.

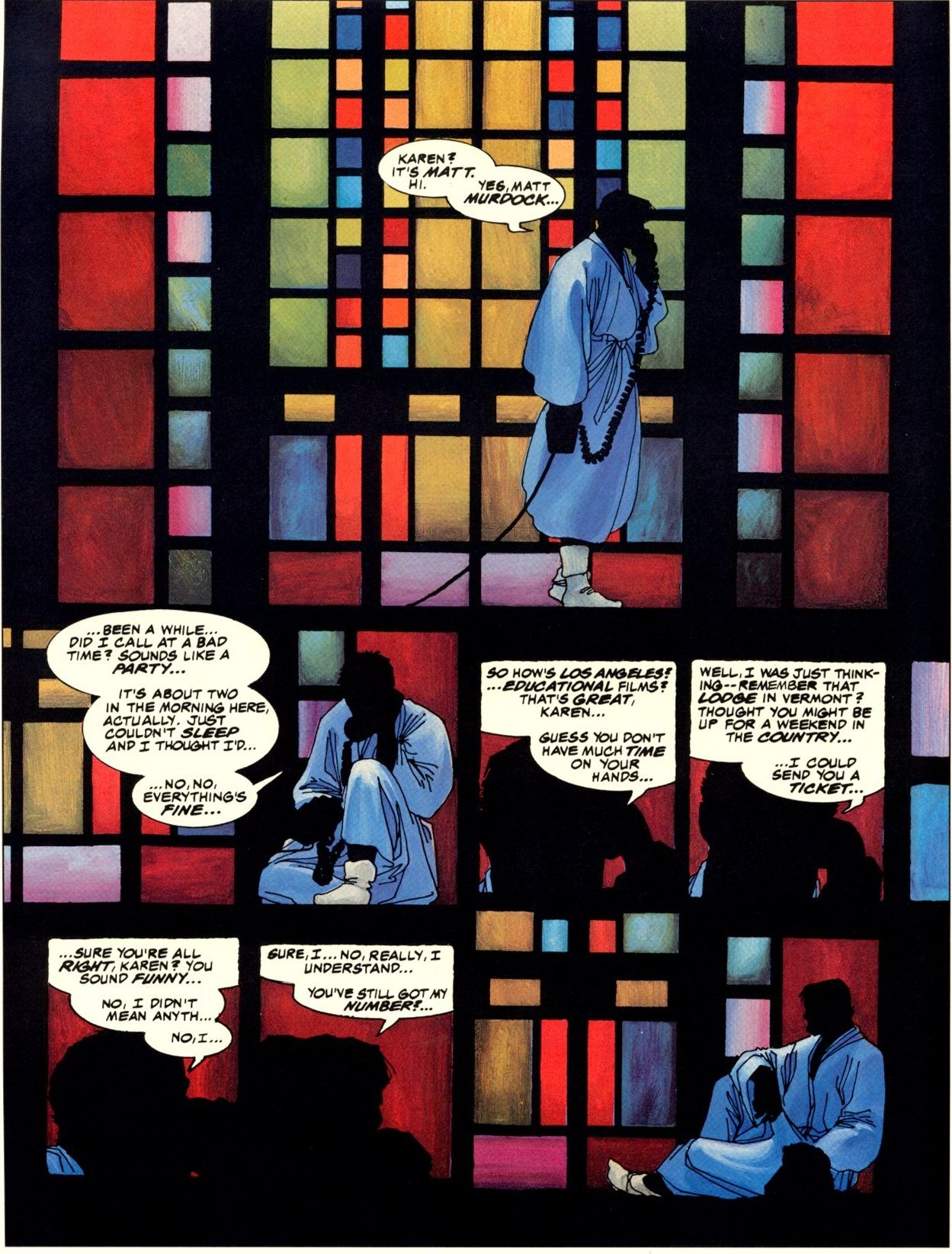

Joey: I think your reading of the story is pretty spot on and i couldn’t even imagine really looking at it any other way. I think it’s all the things you are saying too, it’s Miller saying goodbye to his one true creation in Elektra, the superhero genre of where he spent his 20’s creating some of the best comics ever published, and i’d take it one step further and say this is him deciding if he’s even going to draw comics anymore. This is a tale of transition, and in that process you re-assess if you even have the chops to still do it in the first place. Keep in mind this is the first sequential comic Miller had drawn since The Dark Knight Returns, a high pressure follow-up if there ever was one. Miller had been away from the drawing table for a long time having only written for others masters like Mazzucchelli and Sienkiewicz, drew some covers and pinups, and then took 2 years off of comics altogether to work on the Robocop 2 movie. It was obvious to him Hollywood didn’t really want him, so it’s back to comics, it’s fitting he would return to Elektra at that point. That insecurity and desperation is felt in the writing really nicely in my opinion. Scenes of sleepless nights with Matt calling up Karen for a late night hookup or Matt just clenching that briefcase as he hustles through New York City feel so much more real in this book than even Miller’s other Daredevil work.

The art on the other hand feels much more open to experimentation, and much more confident in it’s own skin. Miller in collaboration with master colorist Lynn Varley attempt something new on almost every page, whether it’s a layout or framing or a color choice. Miller’s art had changed a lot since he started Daredevil and it would change a lot again after this book, but it’s cool how you can see him almost revisiting all the styles to that point and giving a taste of what was to come. This new format, this new “mature readers” tag, this new imprint, they feel free.

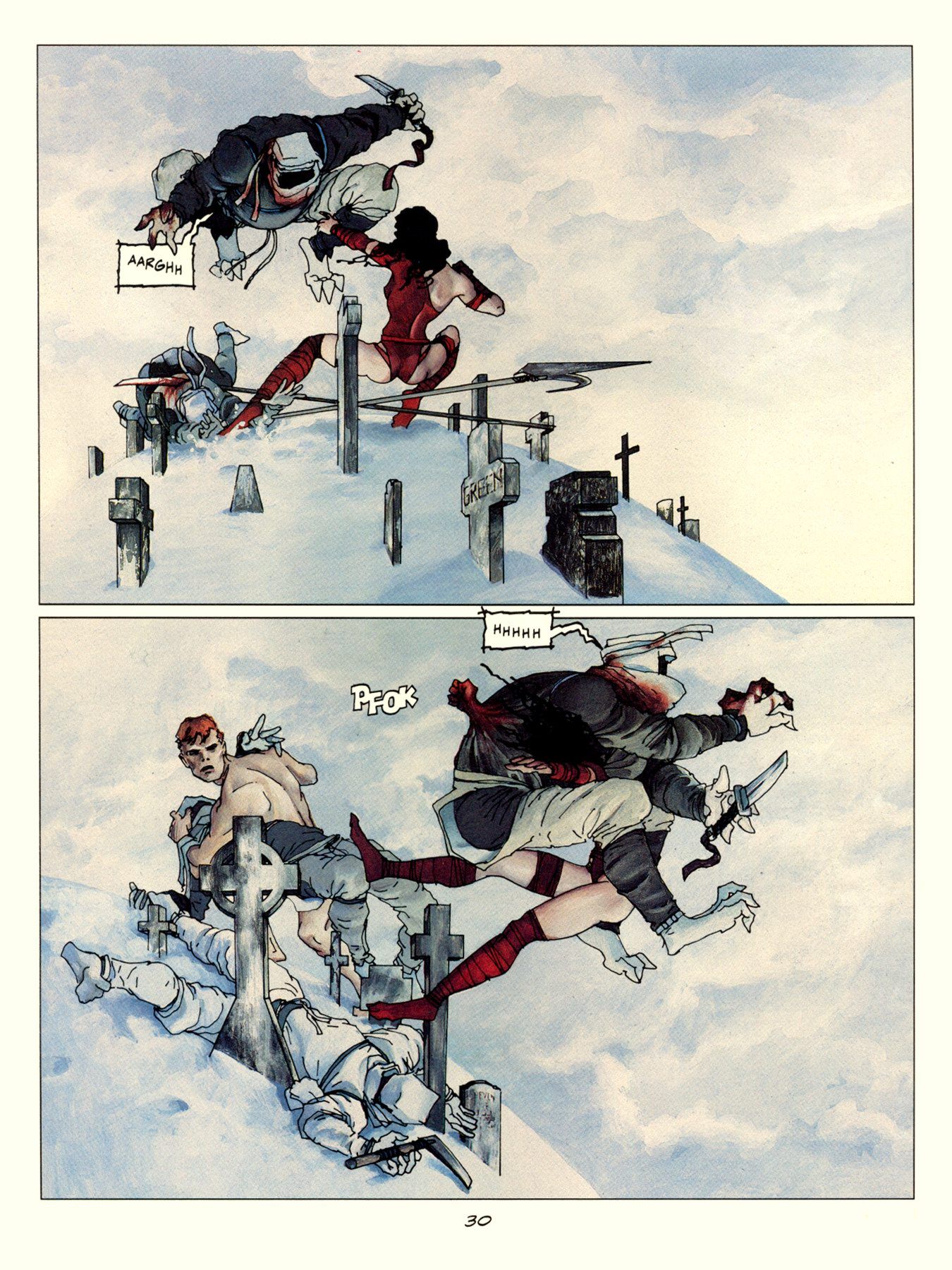

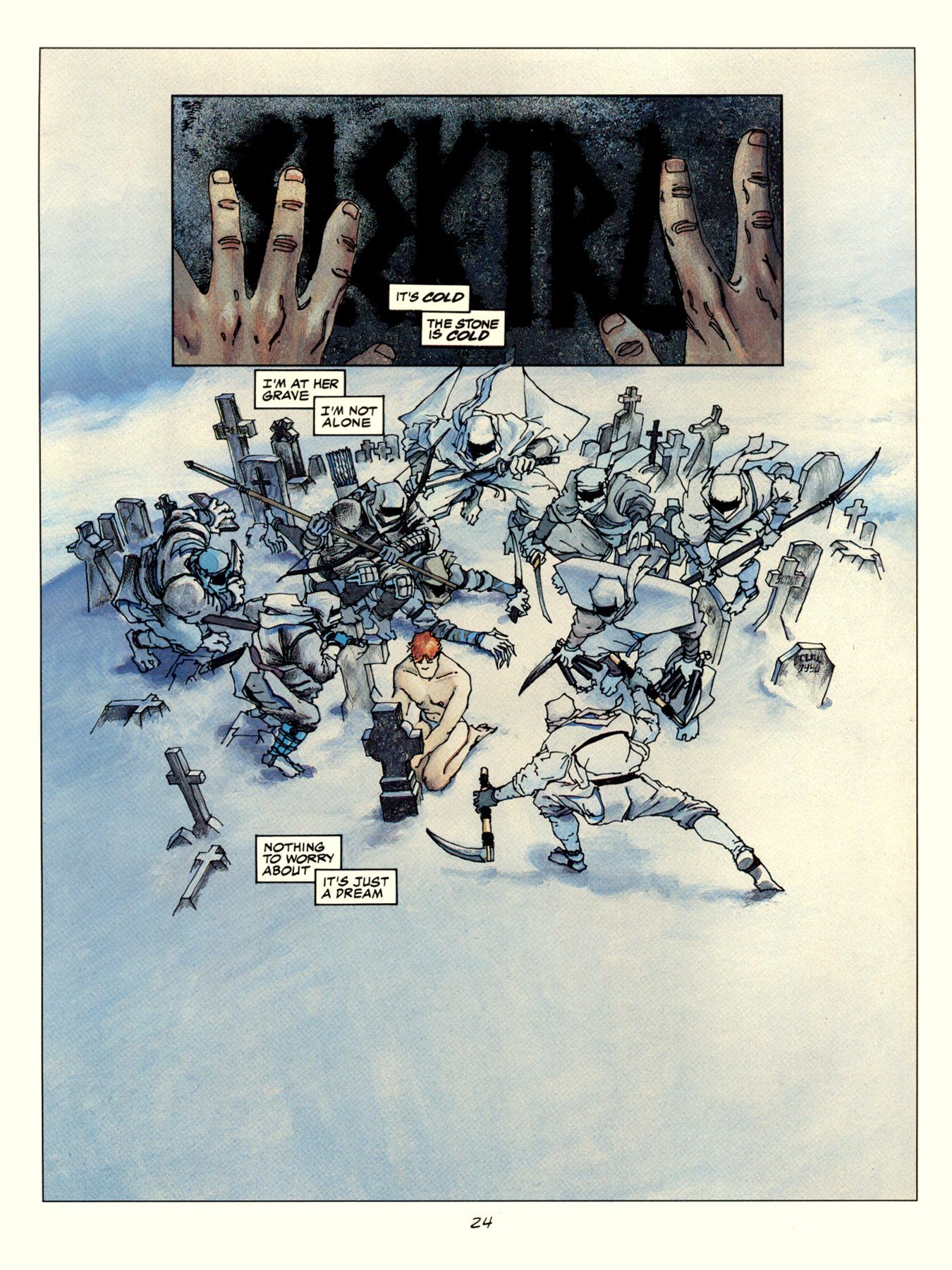

Alec: This book really wants to be beautiful, and sort of is at moments - right before darting back to what we would expect of Miller. The fight sequence in the graveyard is a clear example. He splits this scene two panels per page into wide, horizontal frames, so that the reader lingers on these images like they’re paintings in a temple. It’s not a case of moving a pair of eyes through a set of actions as when, like later in the book, his panels are small boxes littering the page, broken down to show the details of a fight. That’s classic Miller! Those graveyard images want to be something else though. They’re about the fight, but not entirely. They’re about those characters - Matt and Elektra - and how they move through space and the nature of their relationship. That sequence encapsulates this book, for me. Because the ninjas in it aren’t a threat. They do not present any oncoming force that will alter anything we know. They are just traffic cones left out for cars to hit, to showcase something about the car.

The question is, is the car really showing us anything we didn’t know? I like this book - mostly as a document of Miller’s career transition - but it’s really just a pretty summary of previously dealt information. And that’s fine. It serves that purpose (mostly well). But this doesn’t have the drive of earlier work. Again, not that it needs to. This is a different kind of project. It’s just something I notice about Elektra Lives Again.

It makes sense for Miller to take this pause and reflect and attempt to write some poetry around Marvel comic book heroes he built a career on. And that’s interesting. But there’s also another part of me that’s just like “yeah, man, that’s something, but what about the stakes?”. You could argue the “stakes” are Miller putting this period behind him, sailing into unchartered territory. It’s not nothing. But for the story itself, there isn’t much. We’ve already seen Murdock lose his shit under Miller’s pen, so the ending (despite that great image of Matt holding her body) comes with little zing. It just feels like an inevitable outcome.

I do kind of like that this book takes writing turns sort of similiar to Ronin, in that it just leaps with little explanation. Like the end battle with whom (I assume?) is the Devil. That move has some tie to the story Miller’s told (that Elektra has returned from the underworld, and the underworld wants her back), but the fact that it’s probably the fucking Devil is awesome.

I also like the touch of dressing her as a nun, to insinuate something about Murdock’s mother, saying something about the women in that man’s life all together.

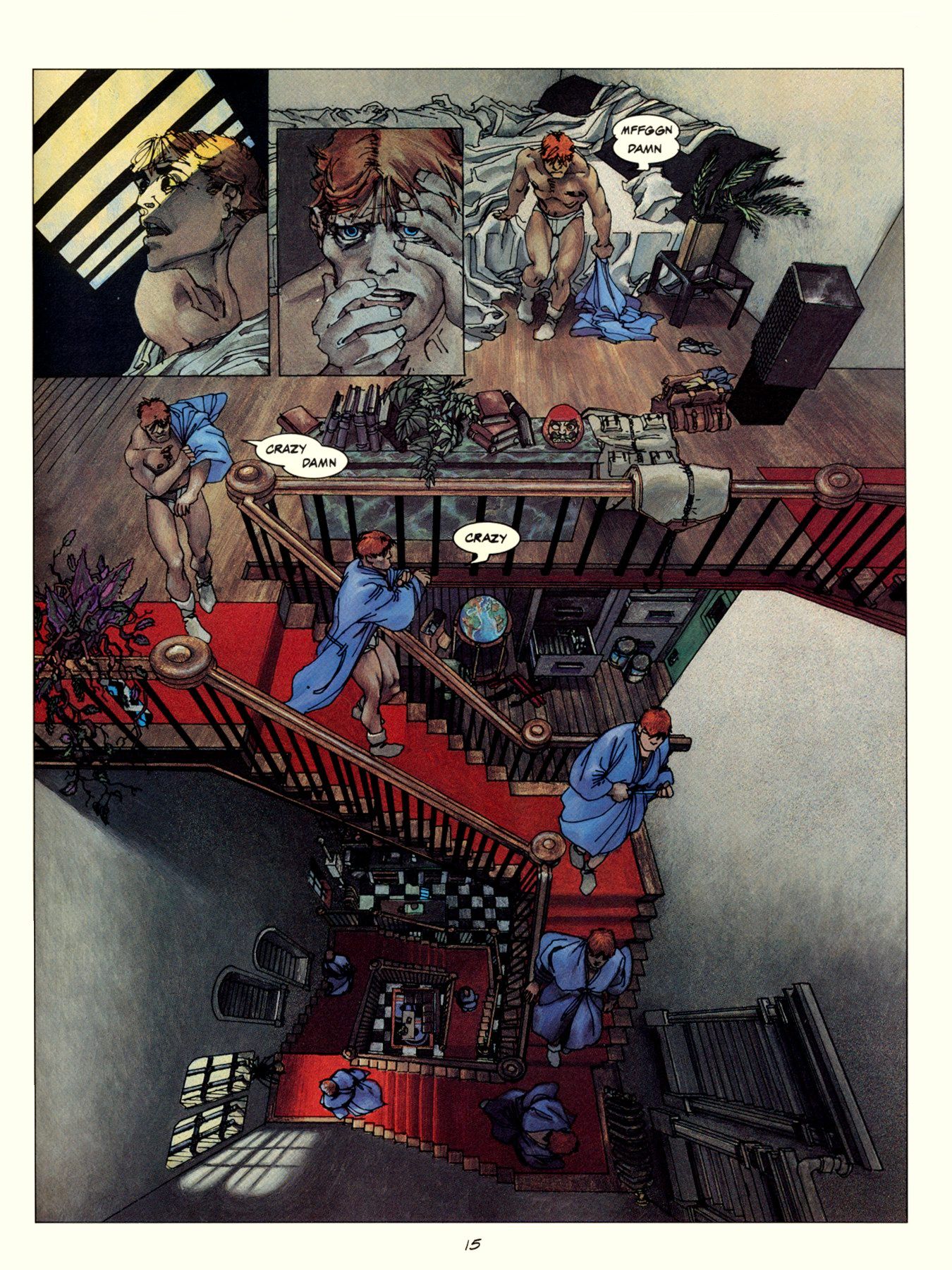

Joey: You say there are no real stakes, but do you think anything in this story is actually happening? It’s really more of a meditation if anything, so the idea that there isn’t a conventional plot moving things forward isn’t an issue for me. I am sure the feelings that Matt has in this story are real but it’s very obviously taking place within his mind (the Escher staircase might be a giveaway).

You mention how Miller frames the scenes like paintings in a temple which is interesting to me as it kind of ties into that whole Catholic motif that runs through the book. Catholic imagery can be found on almost every page in this book whether it’s literal or homage. Starting with the church walls that adorn the first few pages which is mirrored in the layout of pages 16-17 with that stained glass effect while Matt is on the phone and echoed later in the blankets of his affair with his client on page 23. Even the bedroom layout in that sequence mirrors the cathedral layout from earlier in the book, right before Matt does a version of Miller’s signature hero running on the wire scene where he coincidently walks on water. Dante’s Inferno comes to mind as well as Matt descends down the Escher inspired staircase into his own personal layers of hell. Not to mention even the idea of resurrection is very tied to that particular faith. Catholicism is nothing if not guilt and forgiveness and this book wrestles with those concepts at every turn, “Downwards is the only way forwards” after all.

It’s also fitting that a book that is so entwined in catholicism would feel so European. Miller made no secret of the fact he was influenced by the likes of Hugo Pratt, Moebius, Bilal, etc. but you really feel it in this book full on, and the format really drives that home. Miller starts out the book with his usual more crowded paneling but around page 15 he really starts letting the images breath. The overbearing white of the snow in the cemetery on pages 18-19 really hits you more than it would in a single issue, it just engulfs you in this format.

Alec: Whether it’s happening or not doesn’t matter because both scenarios lead to the same, inevitable outcome of Matt giving up the ghost. I’d prefer to see this story as more than just a nightmare, though, because that creates something interestingly unhinged in its delivery versus just a dreamscape where leaps are easily taken. But as you point out, it likely isn’t. It’s just a trick of the mind.

And as we both mentioned, the cause for this project excuses any need for stakes, but I still missed Miller’s forcefulness and energy while reading it. It’s not bad because it lacks a lot of that. It’s just a different thing. But personally, I always invested in the sense of motion much of Miller’s work puts forth, but (as I mentioned before) this book exists to restate and finalize much of what someone reading his Daredevil work knows. Elektra Lives Again is well-practiced, not like his other work where it seems he’s chasing something. It’s more about images settling into their frames than working against them.

Joey: You had mentioned to me that this book reminded you a little of The Dark Knight Strikes Again, was that in reference to it just being a kind of transitional work or did you feel there were deeper connections? The idea of freeing a creation from an interpretation of the author certainly runs through both, so that’s not really an off base comparison.

Alec: There is a Dark Knight Strikes Again comparison to be made between it and this book. Surely, the mission of freeing creations from their makers and owners is a commonality, but both also reflect on previous efforts and their lasting effects. We’ve covered how Elektra tackles this. With DK2, the past haunts by association of its precursor, The Dark Knight Returns (a book with a legacy I’m sure anyone reading this knows), and by Dick Grayson’s fate long after his time as Batman’s faithful sidekick, Robin.

It’s an essay in itself to go into particulars on this argument, but according to the basic plot of DK2 it’s pretty clear Grayson is the ghost causing trouble in Batman’s world, and he likely came to this state position because of the Batman’s influence (see All-Star Batman and Robin, the Boy Wonder). DK2 positions Grayson as the Dark Knight’s big failure, the son he failed to raise. That’s streamlining it, some, but that’s it. Rather than mold Grayson into a positive force on the world, he mislead him to become a twisted, chaotic force of bad, showing that the Batman’s life mission might be his alone, and not teachable to others. This connects to The Dark Knight Returns in that it swept up the comics form and influenced people to consider the medium in a certain, superficial way (see the dark, gritty superhero comics of the late 80s). Where Miller may have wanted DKR to encourage people to test the medium’s potential in their own way, he actually overpowered them. Another failure, of sorts. You may even read DK2’s post-9/11 concern as a way of processing a tragedy brought about by a terrorist group who was sickened by the West's own, overbearing influence. That event spawned its own long-felt, world-changing repercussions, obviously.

All efforts with lasting impacts. DK2, like Elektra, is a means to somehow free one’s self of those old commitments and shackles. The difference is that DK2 actively confronts these ghosts while Elektra mythologizes them.