Reading about all the news out of San Diego, it amazes me all over again how it's okay to be a superhero fan today. For crying out loud, as I write this Julie is watching Comic-Con television coverage in the other room.

It sure didn't used to be that way. Once upon a time, it could get you beaten up.

Thinking about that reminded me of the first time I ever met a real-life superhero. In the sixth grade. It happened like this.

*

I never needed the X-Men explained to me. I completely understood the concept of mutation. I was a book nerd that was born to a jock and a cheerleader.

I got picked on, harassed, and occasionally beaten up for it. A lot. But the worst part was, when the bullying started for me in the second grade, my own mother and father dismissed it with the clear indication that they thought I had it coming. Every time I tried to talk to them about it their advice was always some variation on, “Well, do you have to be so weird? Couldn’t you try to fit in more?”

Of course I had tried. (What an idiot question. Had they never MET a school-age child?)

But fitting in would have meant being good at sports– which would have meant, well, having a whole different set of reflexes. Actually, it would have meant having a whole different body. And that ship had sailed.

Moreover, reading and books were the only thing I had that brought me any joy. Classwork was the only place I was ever allowed to feel successful at anything. The library was the only place at school I felt comfortable. At least there I could get away for a while... and Mrs. Hunter, the librarian, was a thoughtful, gracious southern lady who always had time to talk about books or suggest one I might like.

So, yeah, giving up my ‘bookworm’ ways wasn’t happening either.

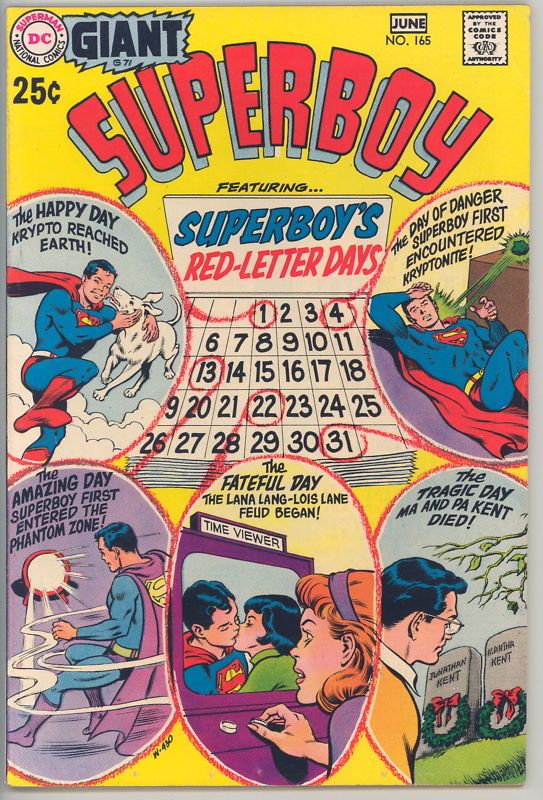

Far and away, though, the most despised thing about my 'weirdness,' as far as I could tell, was reading comics. My mother hated that I loved them so much. (I documented that already in this space, here.) She would let me spend my money on them, but it was always with reluctance; she would try to divert me with other suggestions first, and then would come the exasperated sigh and the head-shaking about how they were so trashy. "Trashy" was kind of Mom's bête noire, and the idea that other people might think that of us was something that kept her awake at night.

Of course, I was not to be diverted. I suspect if you are here reading articles on CBR, you probably already know how hard it is to divert us fans from the comics we want.

But the battles over comics at home were nothing compared to the hell that would rain down on a kid who owned up to liking superheroes at school, back in the late sixties or thereabouts.

See, here's the key difference between now and then. Today, if you bring up Batman or the Joker to non-comics people, they're likely to reply with something about Christian Bale or Heath Ledger. Maybe some will mention one of the animated series, or how Nicholson's Joker was better than Ledger's. (Of course, if you are here on CBR reading this, you know that Mark Hamill's was better than both.) But I digress. My point is, today you'd just get conversation.

But from 1969 to at least 1985, you would almost certainly get this response--

"Oh, yeah. Na-na-na-na-na-na-na-na-- BATMAN!" Then snorts and guffaws.

Seriously. It was inevitable. A conditioned reflex.

You may have noticed that comics fans of a certain age-- pretty much anyone who came to superheroes before the mid-1980s-- have almost a pathological hatred of superheroes that are Not Serious. I can't prove it, but I'm pretty sure you can trace a lot of this to people jeering at them about the Adam West Batman.

And his brethren. There were a lot of silly, not-serious superheroes between 1966 and 1970 on television.

Why not? Batman was a hit. Hits get imitated. For about a year and a half there, we were inundated with silly slapstick super-people. Now, some of these were pretty good-- The Mighty Heroes was a great show and I'd be all over a legitimate DVD set of that series-- but they also provided great fodder for people to sneer at the whole IDEA of comic-book superheroes. The content was secondary; after sixteen months of Batmania, the damage was done. The public perception had cemented in place. To most people, Adam West's version was what superheroes were.

And once it got out that I liked that stuff... well, that was it. Only once did I make this mistake, but once was enough.

I had brought a comic with me to school, in the third grade. I'm not sure why I'd brought it-- I mean, I kind of knew which way the cultural winds were blowing, even then-- but I probably just wanted to read it. (I vaguely remember that the teacher had suggested to bring along extra reading if we finished early, or something. And I always finished early in the third grade; it wasn't until midway through high school that I learned to be a slacker.)

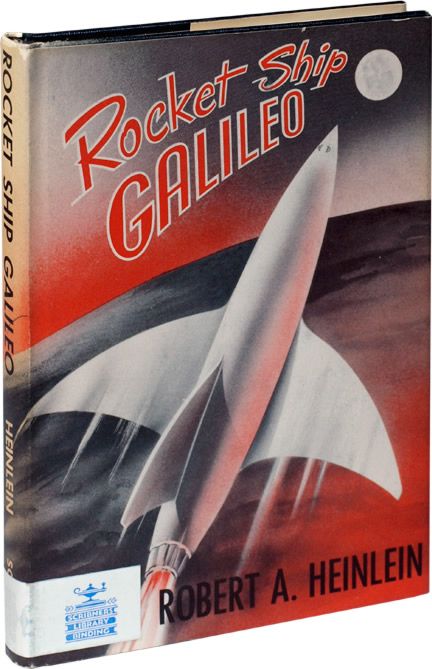

I don't remember the reason for bringing it, but I remember the comic. Vividly. It was Superboy #165.

When I pulled it out for extra reading time, though, the teacher had frowned and said, "Superboy is not appropriate," and that quickly, my life at school took a nosedive. That's all it took-- the damage was done. A ripple of giggles and sniggering went around the room. Superboy. NOT APPROPRIATE. Hee hee hee!

At recess I knew better than to try and socialize. I'd already been a jock piñata for the last year or so, for the great crime of being good at books and bad at football. Now Inappropriate Superboy had assured that I would be their favorite one for the remainder of elementary school. Unless we moved away... ideally, by going into Witness Protection.

So I'd found a remote area of the playground, back by the trees, with the vague idea of hiding out. I had the comic with me, thinking, well, I wouldn't get told to put it away at recess and I could at least read the thing and salvage that much. (Despite the day's earlier public shaming, I still loved reading about Superboy.)

But a posse of my usual tormentors showed up -- about six of them appearing out of nowhere all around me, like ninjas. "Tell us about Superboy, Hatcher."

Today I'd be able to snap off a one-liner like, Superboy? He's busy screwing your sister, because he's invulnerable to the VD she gave everyone else. But at the age of nine, all I could stutter was, "Well, he's-- it's when Superman was a boy."

"NOT APPROPRIATE!" they chorused, and went into paroxysms of laughter.

Then Andy, the largest of them, said, "Let me see it," and grabbed the comic out of my hands.

Instantly it was a game of keep-away. I tried lunging for it and got shoved to the ground. Then for me it was about not crying, not saying anything, not giving them any more ammo to work with... just somehow take it, outlast them before the tears came.

Andy leaned down where I was sprawled and thrust the Superboy forward. "Here."

I grabbed for it and Andy yanked it away. The cover tore.

"Aww," Andy sneered, and dropped it in the dirt.

I lay there, glaring, everything I had put into NOT CRYING, though I desperately wanted to. I could feel it welling up, choking in my throat.

I was literally saved by the bell... the one signaling the end of recess. Andy and the others, still laughing, started back towards the school.

I put my torn comic back in my bag and got up and brushed myself off. At that point, nothing short of time travel could have saved me at school.

One comic. Out in the open. That's all it took, back then.

*

I settled into a sort of furtive, fugitive existence, my books and I. I had the school grounds mapped out in my head as SAFE and NOT-SAFE… if I stayed by the steps with my library book, I was in clear view of the teacher on playground duty; if I waited in the classroom at the end of the day as long as possible and then bolted straight out to the school bus, I had a pretty fair chance of getting through unscathed. Take the back stairs at the end of the hall to the cafeteria, not the front. And so on. Workarounds.

From the third grade to the sixth, I lived in a constant state of terror at school. It wasn’t that I was scared and shaking all the time… but I was always tense, always ready. I knew that at any moment, from any direction, Andy and his crew of other big jock kids might materialize and amuse themselves by shoving me, grabbing my book away and tossing it back and forth to one another, or just dropping it on the ground and grinding it beneath a foot. Sometimes the shoving turned into hitting.

The worst thing about it, though, was that I didn’t have anyone to confide in, because my parents had taught me that somehow, my "weirdness" meant that I had it coming. I’d come home with torn clothes or a damaged library book we had to pay for or– this was the worst– broken glasses, which were expensive. And Dad would grunt in disappointment that I somehow wasn’t tough enough to dispense a beatdown, and my mother would anxiously inquire what I’d done to make them mad.

I learned from them that there was no point in telling an adult because nothing would be done except I’d be told to just fit in better, be more athletic and popular. You know, like I was somehow able to just do that. So I hunkered down with my books as best I could and tried to block it out. You get to where you just learn to live with it.

So what changed?

Towards the end of my sixth grade year, Andy thought of a new trick. He would come up to me at random moments during the day– recess, lunch, P.E., in the hallway– and deliver a whipcrack slap to the face.

It wasn’t like getting hit with a fist, but it hurt, and it often knocked my glasses askew. I had a terror of them getting broken (actually broken again, because bullies are hard on horn-rims and I'd already gone through a few) because I’d get in trouble at home for "not taking care of my glasses."

And it was humiliating. What delighted Andy about this new diversion so much was that this clearly implied I wasn’t even man enough to rate a fist. Just a slap.

A kid I knew named David witnessed this once– I guess you’d call him a friend, we didn’t hang out anywhere outside of school, but we could have a conversation without him jeering or trying to shove me. We were on the front steps waiting for the school bus to take us home and Andy brushed by and grinned, "Hey, Superboy." Slap. Then he waited to see if I'd say anything, but I just shook my head and Andy went on to the bus, looking disappointed.

David said, “Dude, why do you let him do that?”

I stared blankly. What could I possibly do?

David said, “Seriously. I’d nark him out. Tell the principal.”

We were outside, about to get on the bus. I saw our principal, Mr. Pokarney, standing by one of the other buses– the one I rode had yet to arrive– and I was ready to try anything. I ran up to Mr. Pokarney and blurted, “Andy N___ has been picking on me for years and now he’s hitting me in the face, can you make him stop?”

I was almost crying but not. I must have looked ragged and desperate and crazy. Mr. Pokarney, who was a grim-looking, hatchet-faced man with a very scary voice, knelt down and took me by the shoulders. I thought Oh shit I’ve had it. Now I'm really in trouble.

He said, “Andy is hitting you?”

I nodded.

Mr. Pokarney looked at me for a moment. Then he said, “Greg, I will get to the bottom of this. It’s the end of the school day now but tomorrow morning you will come to my office and we will talk about it.”

I went home, wondering. I didn't think I was in trouble, exactly, but usually that's what it meant when Mr. Pokarney swore to a kid that he was getting to the bottom of something. It was hard to tell with Mr. Pokarney because he wasn't exactly a friendly, approachable guy. My memories of him are that he was a great, gray monument of a man. His head looked a little like one of those stone heads on Easter Island but with black hair on top slicked into place with Brylcreem, and silver thickly-framed spectacles parked across his nose, looking more like a windshield for his eyes than actual glasses. You could tell he cared about all of us kids, but it was in a patriarchal, no-nonsense kind of way.

The idea that he had actually meant Andy was in trouble? I didn’t dare hope. To have it just end? Could Mr. Pokarney do that? In Sunday School I had prayed to God about it and begged Him to stop it and HE hadn’t. I figured that meant nobody could.

The next morning– first thing– I was called to the principal’s office. There was a murmur of giggles in the classroom, because that always meant you were In Trouble. I went, not at all sure I wasn't.

In the office, Mr. Pokarney's voice was tough and gritty like it always was but it was lower, and he looked me right in the eye. The first thing out of his mouth was, “I am sorry. We didn’t know. We should have. How long has this been going on? With Andy.”

For a second I could only stare in utter disbelief. He was taking me seriously. More, he was on my side.

Unless you were one of those kids that got picked on in grade school-- picked on daily, mercilessly, for years-- I don't think I can adequately put across in words what that simple fact meant to me. The single most powerful adult in my grade school knew, knew the second I'd told him, that what Andy and his crowd were doing to me had nothing to do with weirdness or comics or being a brainiac or any of that stuff. No, he just knew what was happening to me was wrong. Wrong was wrong and that was all. And by God he was going to fix it. Mr. Pokarney was looking at the situation the way Steve Rogers would have, and at that moment he had his jaw set as firmly as any Kirby Captain America drawing I'd ever seen.

I sat for an hour while Mr. Pokarney asked me questions. He asked for details. He grilled me the way a cop grills a witness. He wanted everything. We took it all the way back to the Superboy incident, even, and bless him, he did not say a word about inappropriate.

When we were done he apologized to me again. Profusely. It almost weirded me out, because Mr. Pokarney was a big scary guy and he was acting like he wanted me to forgive him.

Then he sent me back to class and told me that it would be stopped. He said it like Eliot Ness vowing to get Capone. That time, I believed him.

And it did stop. It stopped that day.

As I got back to class, Andy was called down to the office.

To this day I don’t know what happened, except Mom told me years later that according to the call she got later that morning, Andy had confessed almost immediately, and then completely broken down. Mr. Pokarney had reduced Andy, the terror of my existence, to a sobbing mess. I have no idea what Andy's parents said when they were called, but I know that they must have been. For her part, Mom always expressed shock and surprise that I'd let it get so out of control, that I had never explained it to her... conveniently forgetting all the times I'd tried to and been brushed off. (Note, even after the principal of the entire school had called to walk her through it, Mom still found a way to make it about me being weird, and somehow my own fault. That particular dynamic between us never changed, not to her dying day.)

But all that comes from piecing together secondhand stuff from other accounts years later. What I know happened is this.

That morning, after his session with Mr. Pokarney, Andy slunk back into class and whispered an apology to me.

"Hatcher... I'm... uh... I'm sorry. About all the stuff I did. Really." He whispered it because it was class and we weren’t supposed to be talking, but he couldn’t stand to wait. Andy was a beaten man and he was genuinely sorry.

Here’s the really weird thing. I could tell Andy was broken. Mr. Pokarney had destroyed that kid. He was slumped and shaken. This was for real. At that moment I owned Andy. I could have taken my revenge any way I wanted.

But I didn’t want to.

Honestly? He looked so small, so repentant, so... crushed, that I kind of pitied him. It was enough. Suddenly, I was satisfied.

So I said okay, and when he didn't leave I made some kind of dumb joke, trying to get him to laugh. It got a weak smile.

And from then on we were okay.

I didn't have the words to explain it then, and I'm not sure I do now. But I think it was something like this.

It's a comic book cliché, I know. But sometimes clichés are true. I hadn't wanted revenge. I wanted justice. Even after all those years of pushing and humiliation and torment... All I wanted from Andy was the honest acknowledgement of wrongdoing. That what had been done to me was not supposed to happen.

And Andy... I think he had been expecting the same from me that I'd gotten from him. When I let him off the hook, he was so grateful that it morphed into some kind of new respect. I still don't know why I did that. It certainly wasn't because of my innate goodness, or anything like that. In my adult life there have been many times I've been nasty to people I was angry with, sometimes nastier even than Andy ever was to me. But that day... I couldn't do it.

Mr. Pokarney was my hero from that day forward because he made all that happen. He took one look at me and knew I had been wronged. One look. After years of me trying to EXPLAIN it to my actual parents. What's more, he fixed it in less than twenty-four hours– to the point where the bully didn’t just stop bullying but HE knew it was wrong, too.

I was eleven. To an eleven-year-old, how is that not superheroic? Mr. Pokarney didn't even have powers. Well, except for his scary voice.

*

When I see news items about teen suicide, or even about school shootings, I always flash back to my days in grade school and how I would wish Andy was dead, or sometimes I would wish I was dead, and think that if I'd had a gun then, quite possibly one of us would have been. The desperate wish to somehow make it stop, the frustration when it never does... sometimes no price feels too high if it means putting an end to it. It never surprises me that occasionally kids break under that pressure. Because it's really that bad.

Today the word's out on bullying, and many-- but not all, not even most-- schools have a zero-tolerance policy in place. Too often, it's dismissed as an inevitable part of growing up, some kind of rite of passage that everyone goes through, and just not that big a deal; even though there's mountains of evidence that it does terrible damage to kids and there's an actual death toll directly tied to the phenomenon. Nevertheless, there's still the shrug, the kids-will-be-kids response. It persists into adulthood, even-- how many times have you heard someone dismiss horrible behavior on the internet, even stuff like threatening violence or rape, with the comment that that's just the way it is on the net? Sissies who can't take that kind of thing just need to get over it.

As much as I appreciate what Dan Savage and various other celebrities are trying to do with their "It Gets Better" campaign, I have a huge problem with it. At its core it feels to me like just a new variation of look, it happens, get over it.

I always think, You know, the message "It Gets Better" would not have done me a bit of good when I was dodging bullies every day, for years, with no end in sight. Wait till I'm out of high school and it will get better? Really? What was I going to do for the decade before that? If it's so wrong and horrible and damaging, if your whole push is that this should not be happening, why aren't you putting a stop to it right now? Shine a light on parents and educators and youth workers that think it's okay. Make them know that it's not. Not ever.

If Mr. Pokarney had taken the attitude that the "It Gets Better" people have, that you just have to wait it out like bad weather, there's a good chance I'd be dead now, another teen-suicide statistic. He didn't. He dealt with the problem at hand, while it was actually happening. And I have never forgotten the example he set.

Like I was saying to someone on this very site the other day, no, you can't clean up the whole world. But by God you can make sure that at least your corner of it is free of bullies and creeps. You have to start somewhere, or it never will change at all.

*

Andy and I were never friends, but we were friendly from that point onward. I was still a book nerd and he was still a star athlete, so our paths didn't cross much. But if we ran across one another we'd say hi, and sometimes in high school he'd pull over and give me a lift in his car if he saw me walking.

To my knowledge he never picked on another kid again. Whatever Mr. Pokarney had said to him, it had stuck. Sometimes, in later years, I thought about asking Andy about it but our peace felt fragile to me; I think it was based on my not taking the chance to humiliate him when I'd had it. Bringing it up to him, even years after the fact, felt like it would be some sort of unspoken treaty violation.

Today, I’m fifty years old, a teacher at a local middle school, and I take a quiet pride in the fact that my classes are safe places for all the comics and book nerds who want to make their own stories. Sometimes a bully tries to get away with something and he gets taken down HARD with what my wife calls the Scary Teacher Voice. I’m not done till that kid knows bullying is wrong. Because that’s my job.

The last time I had an incident in class, early in the fall of 2010, Niko and Ciana were jeering at Connor and it was getting mean. I kept the two of them after class and gave them The Talk.

It went something like this: "Look. I don't care what you think of your classmates. I don't insist that you like everyone. I know you're not all going to hold hands and sing Kumbayah. But you will by God be civil and polite when you are in my classroom or you'll be out of here so fast you leave a smoke trail. If I ever hear anything like what I heard today about Connor again from either of you, you're both gone. And your parents will be hearing from me about what shallow and judgmental and self-centered little brats you apparently are when you think someone doesn't measure up to your precious standards of coolness. Understand this -- your ideas about what's cool are never going to matter to anyone over the age of twelve. EVER. So you might as well stop trying to inflict them on kids who have never done anything to you. It's a waste of your time. And if you ever waste my time with this crap again, I will make sure you regret it. FOR YEARS. Do we understand each other? Did I use small enough words?"

Terrified nods.

"Because if it ever happens again, that means you're lying to me now. And that will make me twice as mad, and I'm pretty mad now."

Emphatic, terrified nods. They understood.

"All right. Get out."

Connor's crime, by the way? He has a bad stutter. He was way more gracious to them than they deserved.

And that was the last of it. Ciana eventually left Cartooning, but Niko stayed and completely mended his ways.

Now, it's not a big thing that I scared a couple of eleven-year-olds into behaving themselves. But what made me smile about it, a year later, was when I was telling the kids to clean up our classroom and added, "Seriously, now, if I get scolded again about you guys leaving your trash on the table, so help me, I will come down on you like the Hammer of God."

I was kidding, of course. Well, mostly. But Niko, a few feet away, said, "Yeah, man, I've seen the Hammer of God. It's no fun."

I smiled because I knew it wasn't really the Hammer of God. No, I was channeling my childhood hero... Mr. Pokarney. The lesson had stuck. For both Niko and me.

See you next week.