1.) It seems appropriate to begin a discussion of Alison Bechdel's Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama with an anecdote about myself, rather than something about the cartoonist, her book or its subject matter.

I used to work at a library that was in the midst of reorganizing certain sections of its adult collection along a more bookstore-like model, with books of certain genres being grouped together to be more browsable than the previous, more standard set-up, which had all the non-fiction shelved according to the Dewey Decimal System and fiction by the author's name.

One day I and another librarian were pulling memoirs to put in the newly designated memoir section, and she mentioned something about a "Mommy Didn't Love Me Enough" books, which I didn't quite catch. "Oh," she explained, "That's what I call some of these memoirs, 'Mommy Didn't Love Me Enough Books.' Once you get past the particulars, that's what a lot of them boil down to."

Are You My Mother? is Bechdel's follow-up to Fun Home, her 2007 memoir about her father, and focuses on her other parent. As I was reading, I suddenly recalled that conversation from a few years ago, and wondered what my former co-worker would have made of this book, provided she would be able to read all that much of it before giving up.

I have to assume she would regard it as the nee plus ultra of "Mommy Didn't Love Me Enough" memoirs.

Only in comics instead of prose.

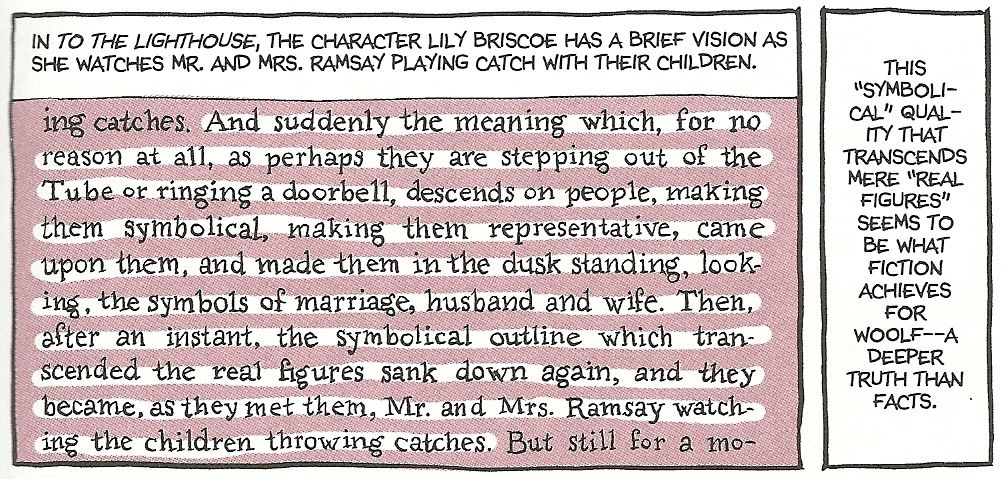

2.) I mention how difficult the book might be to read for that co-worker not merely to reflect its quality, but because of its subject matter, which that particular person didn't find terribly appealing, and also because it is told in a graphic novel format, which a lot of folks not used to comics can find challenging. It's a particularly dense and textured form of comics, too, with a lot narration boxes, often super-imposed over close-up panels featuring drawn reproductions of pages of books Bechdel is reading within the narrative, with particular passages high-lighted.

While the artwork is a great deal more accomplished than that of Fun Home, I found it an inferior book in almost every other regard. The word "sophomore slump," which I hear applied to popular musicians who exploded into public consciousness withe successful, well-regarded albums releasing disappointing second albums more than I hear it referred to comics or the works of other media, came to mind, and it hung there while reading Are You My Mother? It hangs there still.

Looking at Bechdel's career as consisting of exactly two original graphic novel-format books, it seems appropriate ... at least until one remembers Bechdel's a cartoonist who produced the strip Dykes to Watch Out For for 25 years. She might be relatively new-ish to books, but she's got writing and drawing comics in general down pat.

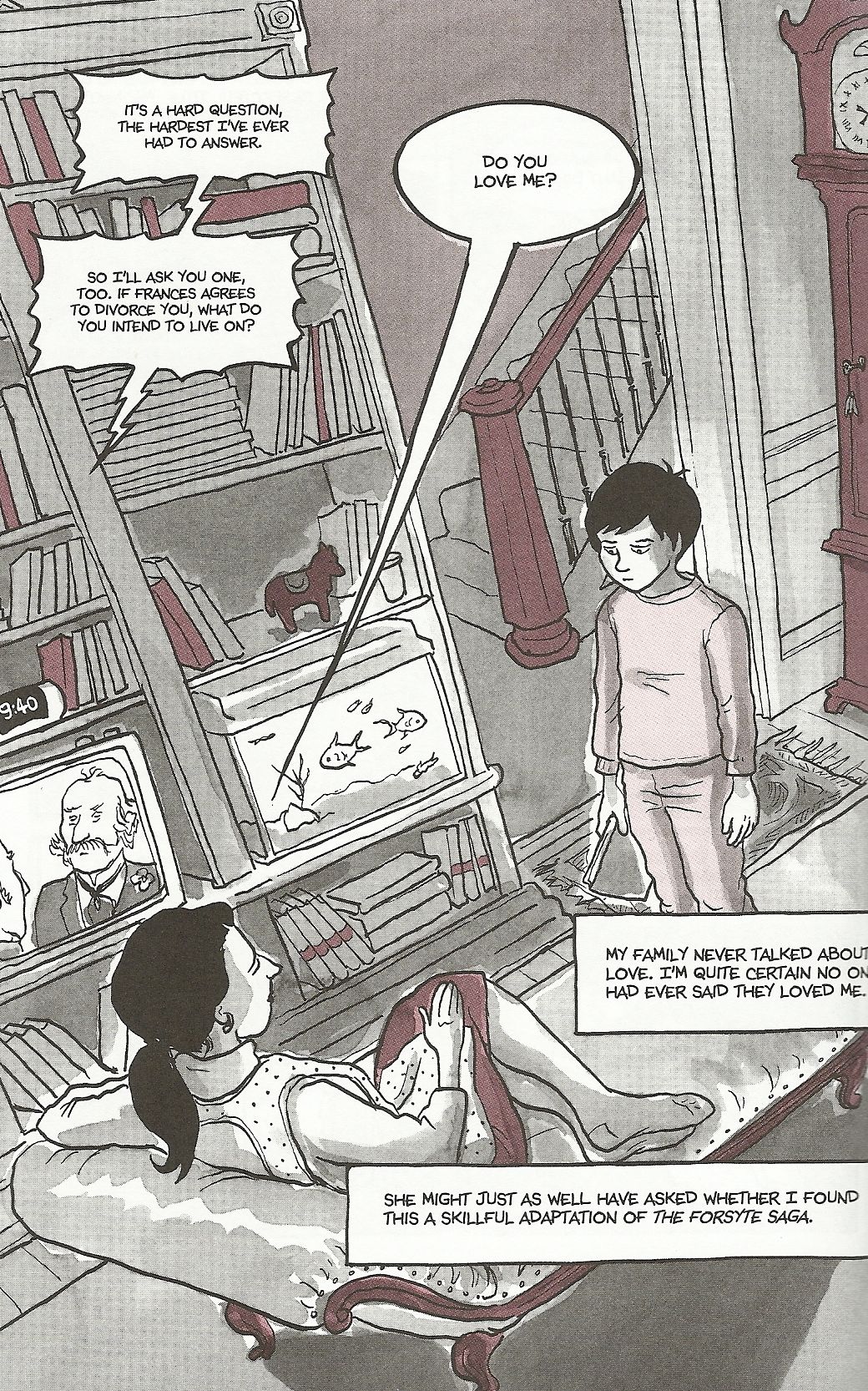

3.) Despite the title, despite the temptation to view it as a companion to Fun Home, as a book about her other parent, it's not really about mother — at least, it's not about Bechdel's mother as much as it is about Bechdel, and it's not really about Bechdel as much as it is about Bechdel's relationship with her mother.

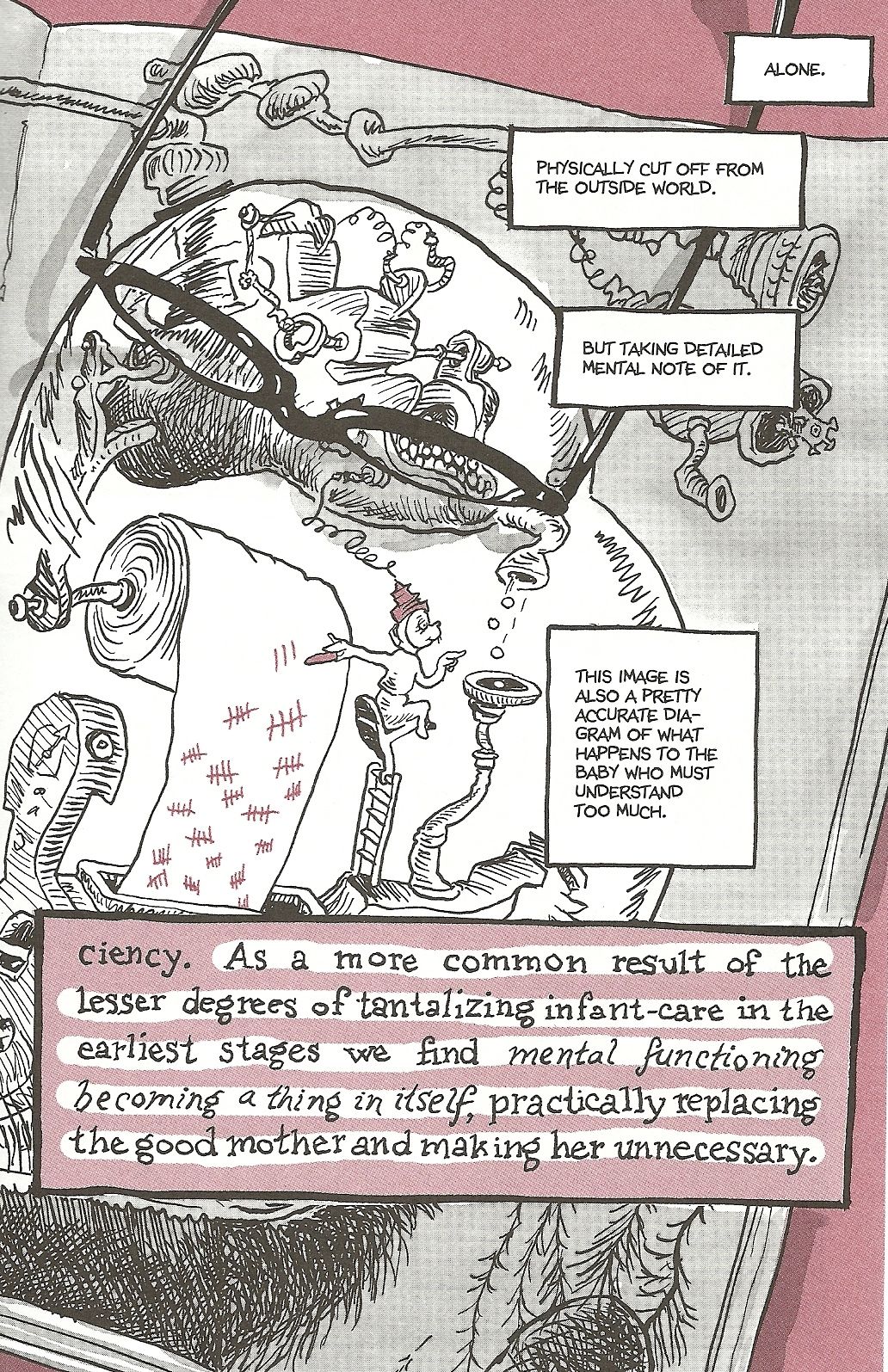

Or, to try and put it as precisely as possible, its Bechdel's analysis of her lifelong analysis of her relationship with her mother, which she's sought to accomplish through years of therapy, self-driven biblio-therapy in which she reads sometimes-heady and fairly dated psychology texts and looks for herself in them and through conversations about their relationship with her mother herself.

Each chapter opens with a dramatization of a dream of Bechdel's, and then cuts to a series of often non-linear anecdotes ranging through time and space from Bechdel's childhood to her mother's life before Bechdel's birth to the work and life of early-20th century pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, whose books provide springboards for much of Bechdel's thinking on the subjects of a child's relationship to her mother (and her own relationship to her mother) that make it to the pages of this particular comic book.

That said, "Alison Bechdel's memoir about her mother" sure is a much easier pitch than any attempts to formulate a more accurate description of the book's subject matter, and I suppose it's true enough.

4.) While reading, I kept imagining other books Bechdel could have created, suggestions of which appear in passages of this book. Like, perhaps, a straight biography of Winnicott. Or a straight, chronological biography of her mother, who certainly had an interesting life, and whose relationship with Bechdel is as reversed of the traditional adult child/mother relationship as to be occasionally darkly humorous. Or a history of Bechdel's relationships or experiences with psychoanalysis and therapy and mental illness/behavioral problems, all of which weave in and out of the story she ultimately tells, which is the story of...

Well, here's the strange thing: Bechdel obviously spent years researching and collecting information for the creation of this book, which included her transcribing phone conversations with her mother while her mother talked to her in an attempt to get her voice just right, but the story of the book is that of the creation of the book. It's the story of a cartoonist who wants to do a book about her mother, and struggling to understand herself, her mother and their relationship in order to do so, all the while writing and drawing about that difficult creation process.

At the book's climax, Bechdel draws herself talking on the phone to her mother about a draft of Are You My Mother?, and her mother is trying to give her feed back. "It's ... It's a meta-book," she says, while struggling to think of something positive and encouraging to say to her sensitive daughter.

And she's right. It's a meta-book, a book-length comic about the creation of itself ... specifically, the thinking and writing process that went into it.

5.) I wonder why she went with "A Comic Drama" for a subtitle then, instead of the more accurate "A Meta-Comic." The former certainly sounds more widely appealing, and while I imagine the latter might prove something of a turn-off—depending on one's feelings regarding scenes of a writer sitting in her bed highlighting 100-year-old works of psychology or talking to her mom on the phone—Bechdel's previous work, from Dykes to Fun Home, demands a certain amount of attention from a certain segment of her potential audience. That is, whatever Bechdel publishes and whatever she calls it, those of us who read comics, and who think and write about comics, owe it to ourselves to check it out.

6.) That said, I found it really boring, and I had to put it down several times before I made it all the way through, and re-read other portions repeatedly. I'm interested in Bechdel, and I'm interested in her mother (now), and I'm interested to see a smart person wrestle with difficult questions, but it didn't cohere into a comic I found particularly interesting.

Thinking about it now, I'm wondering if it even needed to be a comic book. There is little in here that couldn't have been accomplished just as easily, if not more easily, through prose, and I now find myself wondering if Are You My Mother? might have made for a better prose book than a comic book. Is it a comic book only because Bechdel is a cartoonist?

One of my personal criteria for a truly great comic is one that does something that can only be accomplished as a comic book. If it could just as easily be a film or a novel, then it didn't make use of its medium. In that regard, this certainly isn't a great comic book and, at the risk of sounding overly harsh—my criticism comes mainly from disappointment, after all—and seems to be a waste of the time Bechdel spent drawing it.

Of course, the book's conclusion demonstrates that, whatever we readers may think of the book, its creation proved invaluable for Bechdel herself.

7.) I feel like a heel for not liking it, and even more of a heel for saying so publicly, given how much anxiety Bechdel has or has had about rejection in general, including rejection from her faceless audience of readers. One certainly gets to know the author well enough in this book to like her, to pity her, and to want what's best for her and will make her happy.

I want to have liked it, for her sake, but I didn't.

8.) Another anecdote about me: My sister saw came to pick me up one day, and as she was standing in my doorway, waiting for me to put my shoes one, she saw this sitting on my table and asked, "Why is that copy of Are You My Mother? so thick?"

My sister was thinking of the classic children's picture book of the same name by P.D.Eastman, in which a hatchling asks various animals and objects if they are its mother, the book Bechdel named hers after.

The children's picture book Bechdel references within hers, however, is not Eastman's, but Dr. Seuss' The Sleep Book, in which Bechdel recognized herself as a child ... and even as an adult. This leads to a neat page where Bechdel "covers" a Seuss illustration, one she will return to later in the book.

But why is it so thick? Well, Bechdel's not really asking the question in the title, but wrestling with her own existence and aspects of it as they relate to her mother, and those are issues more than questions, ones that simply can't be resolved with a simple "yes" or "no" like Eastman's bird's question.

I'm glad Bechdel chose that title, though. I imagine parents going to their local library's online catalogs and reserving a copy of Are You My Mother?, and clicking on the wrong entry. I imagine them going to pick the book up, wondering why it's so thick, and flipping through it, to find about 200 pages full of psychoanalysis and the occasional lesbian sex scene.

That makes me smile. So, too, does imagining that little bird hopping onto Bechdel's shoulder to ask her, "Are you my mother?" and, instead of saying, "No, I'm not your mother — I'm a human being and you're a bird," an Eastman-drawn Bechdel pulls out a dog-eared, highlighter-filled collection of Winnicott's writings and begins to explain transitional objects, false selves and Virginia Woolf.

But then, I am easily amused.