Ted McKeever has had a long and impressive run in comics, with work that's spanned Marvel's Epic imprint, Vertigo, DC Comics and Image Comics. As an artist, he's collaborated with a wide range of writers over the years including Joe Kelly ("Enginehead"), Peter Milligan ("The Extremist"), Rachel Pollack ("Doom Patrol") and Lydia Lunch ("Toxic Gumbo"). He worked with Jean-Marc & Randy Lofficier on a trilogy of graphic novels that mashed-up DC's superheroes and classic films, starting with "Superman's Metropolis."

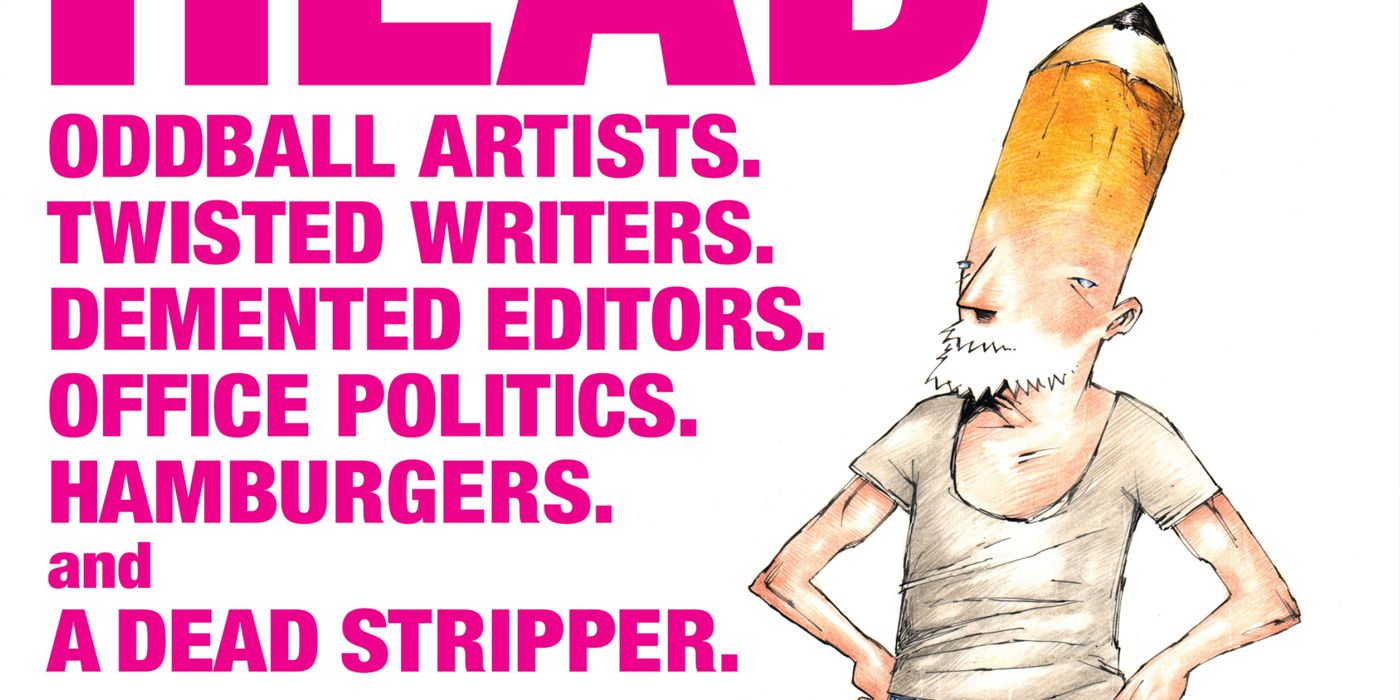

For many people, his most beloved work remains the comics that he wrote and illustrated. From the beginning of his career with "Transit" and "Eddy Current," to "Plastic Forks," and "Industrial Gothic," to the just-wrapped Image series "Pencil Head," McKeever established himself as not a unique artist but a daring storyteller whose artwork was not realistic but was always deeply emotional, which rooted those stories and characters no matter where he went with his artwork and designs.

"Pencil Head" concluded in June and McKeever has announced that he's retiring from comics and pursuing other projects. He's written at length about his decision on his own blog -- writing that the current comics industry "has become less than enjoyable from a creative standpoint" -- and sat down with CBR to look back on his career, starting with its beginning.

CBR News: How did your art style develop? Because it changed over the years, but from the beginning you seemed to have this idea of how you wanted it to look and feel.

Ted McKeever: As far back as I can remember, I've always drawn. My mom had come back from the drug store one day, when I was around five years old, and she bought me this "doodle pad," filled with blank newsprint pages. I can still remember sitting by the window, and just drawing for days with absolutely no idea what I was doing. But I drew, and learned how to draw with each completed page, filling it with some awesomely funky stuff. I know, because I still have that pad -- haven't looked at it in about 20 years though. But the first drawing I ever did is in there.

Anyway, that's how I've always approached drawing. I jump in, start on whatever it is I have in my head, and then basically, make it up as I go along. It's kind of like cooking. You know, taste as you go along. Add a bit more salt, hold back on the butter -- art's the same for me. I have an idea of what I want to do; what I want the finished piece to look like. Then I jump in. Whether it gets there exactly, or not, depends on how focused I am on it. I've always maintained the same basic structure of how I work, along with the philosophy to never use another artist's work to copy off of. I've always felt that if art doesn't come out of your own head, then it's not truly your own.

The bottom line is, I'm constantly developing a style that is, at its core, that five-year-old sitting at the window, scribbling down on blank sheets of newsprint, whatever comes into his head, trying to figure out how to make it look, and work best, with absolutely no idea why, or how. But to just do it.

Your first series was "Transit" which was published in the late 1980s. What interested you in making comics?

I had spent years working in news. First for ABC television as a courtroom artist, and then at the Miami Herald as an editorial artist. During those years I'd seen a lot of stuff, some of it seriously horrendous. Having to then translate what I'd seen into images that were palpable to the general public became second nature. During those years, I started developing ideas in my head to misdirect the impact of what I'd seen, into stories that combined and expanded on those images and situations burned into my head. It was then that I got chicken pox, and had to stay indoors for three weeks.

Like I'd said, I'd always drawn. So, I started putting down all those stories onto paper, and by the end of the three weeks, I had the first issue of "Transit" written, and partially illustrated. I took those pages to a con in Atlanta, where I met Archie Goodwin for the first time. I'd known of Archie from his brilliant contribution to the Warren publications that I read religiously as a kid growing up. His opinion was what I went to Atlanta for. He took one look at what I had done, and simply said "Finish this. Then send it to every publisher you can think of." That's when I knew I had something worth pursuing.

So, I did. I quit my newspaper editorial job, and ended up going with Vortex Comics. They hooked me up with editor, Lou Stathis, and I was off and running. Five issues later, the wheels came off, and Vortex went under. But, by then, I had already started working on "Eddy Current," so I just jumped onto that full-time, and kept going.

One of the things that always impressed was that you had a style, but you were making new books with new characters frequently. Was that always what you wanted to do, make something, then make something different as opposed to say drawing 100 issues of the same series.

Yeah, it was a conscious decision to tell stories. Not "a" story. I like peaks and valleys. I like ends of stories. An end to a story can either make or break it. I've seen films that sucked through most of it, and then had a killer ending that made it decent. I've seen good movies that were totally ruined because of a crap ending. The same with books. And with comics. So, I've always created with the idea of visiting a place, telling its tale, and then wrapping it up.

To do the same characters for that long, year after year -- no thanks. Sounds to me like a nightmare of creative stale.

After "Transit," you made two series with Marvel's Epic line, "Plastic Forks" and "METROPoL." What was it like working at Epic? Who were you working with there?

I had originally signed with Comico to do "Plastic Forks" as a 12-issue miniseries. I had the first two issues, and the first three covers finished, when Comico went bankrupt. Having no idea what I was going to do, or where to go, I ended up talking with Archie Goodwin, who was EIC of Epic at that time, about a series I had started, and the situation at Comico. He said he wanted to see what I had done so far. So, I brought in the first two issues of original art, and the three covers, to his office at the Marvel building in New York. He went through every page, and said, "I want this. Only instead of 12 issues, it's going to be five issues, 64 pages each, and fully paint every page." And that was it. I signed the contract that week. Never once did he, or anyone there, tell me what to do, how to work, change the title, or alter a word. I was just given the keys and let loose. It was an awesome time for me.

Then, after the completion of "Plastic Forks," I approached Archie with "METROPoL." And once again, he took a look at what I had, and gave me the green light. Twelve issues later, I decided to take a brief break, and get the next three-issue "epilogue" of "METROPoL A.D." in the can, so they would come out consecutively, with no delays. But, it was around this time that Archie had left Marvel/Epic and moved over to DC. And, that's when the whole ball of yarn started to unravel. With new editors stepping in, all my previous established plans with Archie were thrown in the toilet, because these new editorial "heavy hitters" came barreling in like a wrecking ball, with absolutely no intention of honoring what Archie had worked so hard to establish. Not only with me, but Epic in general. So, needless to say, "METROPoL A.D." turned into an aggravating shit-show, where the new editor and his lackey assistant, made working there a miserable experience, and the sole reason why I walked away from Epic.

I first got to know your work shortly after that when you began being published by Vertigo and DC. The first project there you did was "The Extremist" with Peter Milligan. How did you end up working at Vertigo?

Right around the time after the "Metropol A.D." fiasco, I got a call from Karen Berger, whom I had met some years prior at a con we both attended in London, asking if I'd be interested in illustrating a series for Vertigo, written by a writer named Peter Milligan. She said that Peter had sent her a plot outline for this series called "The Extremist," that the original artist, Brendan McCarthy, didn't want to do it, and Peter had asked her if I would be interested.

Of course, I said yes. I mean, I read the plot outline, and I immediately started having a clear vision of the lead character's outfit. I put a cock ring as the centerpiece of his face, to see how far they'd let me go. When both Karen and Pete gave their collective thumbs-up, I knew it was going to be a blast.

And it was.

After that you drew "Doom Patrol" for a year when Rachel Pollack was writing the book and I know her run has many detractors, but this was one of the longer-term projects you did. What was it like for you?

Working with Rachel was fantastic. She's such a visionary, that I couldn't wait to get each issue's script. There was nothing she could write that would've been too far for me to draw. And she pushed the envelope big time! Seriously. Menstruating volcanos. Sex ghosts. A talking head in a tray of ice. C'mon, it doesn't get much more fun than that. It also was probably the most prolific time of my career. I was pencilling a pretty tight eight pages a day, then when I got to inking, I was completing an average of three fully inked pages a day. It was exhausting. But, hell, it was a blast. I remember one time I had called Rachel after reading that issue's plot, and leaving a message on her phone, asking her if I could give Cliff, the robot character in "Doom Patrol," a robot penis. She called me back with complete approval, and a few laughs.

That's the time Karen had hired my "Transit" editor, and pal, Lou Stathis. With him on as editor, Rachel writing some awesomely whacked-out scripts, and Karen giving me the freedom to go nuts, and do whatever the hell I wanted to visually, well, that was a damn good year.

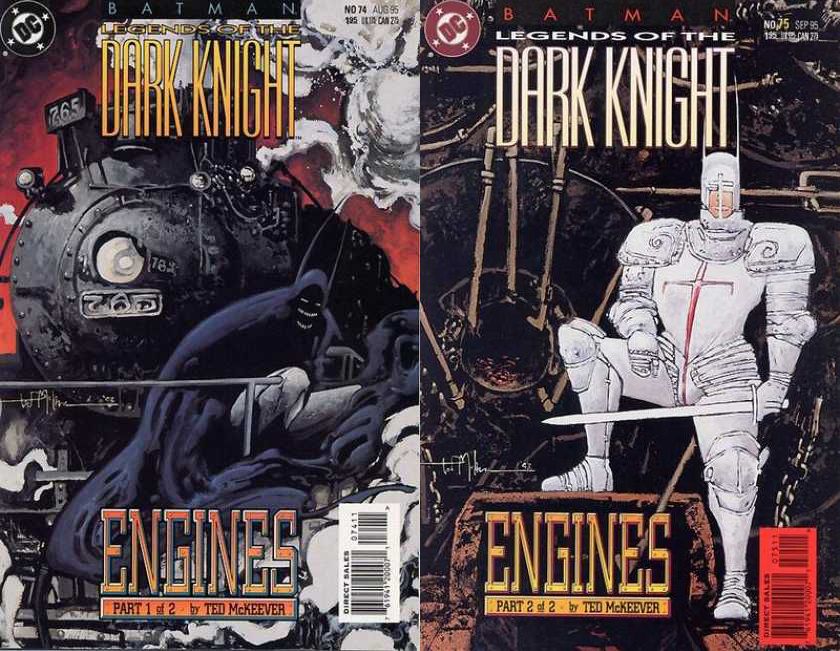

You wrote and drew a two-part story for "Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight," titled "Engines." Archie Goodwin was still editing the series at that point, right?

Yes. Archie was one of the industry greats. That man had so much knowledge of the craft, that working with him was like getting paid to learn the meaning of life from the Dalai Lama. Since we had a sort of unfinished history at Epic, he asked me to contribute a story idea for his "Legends" title.

Having absolutely no in-depth knowledge of the Batman character, I decided to write a plot about a guy who bases Batman on his appearance, rather than who he actually is. I mean, if you look at Batman visually, he looks like he's a bad guy. But, as we all know, he's obviously good. So, I played off those two elements, with the protagonist's inner monologue, slowly understanding who Batman really is. I also figured that if I had Batman say something, the die-hard fans would know I had no idea about their beloved character. So the one time he speaks, I had a train go by, and drown out his voice. Archie gave me the go-ahead based on that plot-point alone. He then once again backed off, and let me run with it.

Around the same time that "Engines" came out, you wrote and drew a miniseries for Vertigo, "Industrial Gothic," which was the first of a few miniseries you wrote and illustrated there. Were you mostly working Stathis at Vertigo or did you work with a lot of people?

I worked with a few editors during my time there. But for the most part, I worked with Lou Stathis. He was my editor on two of my longest running series, "Doom Patrol" and "Industrial Gothic." Those were probably my favorite years working in comics. Mainly because I was working with my good friend.

Lou was a genius. He truly was, in every sense of the word. And "Industrial Gothic" is one of my personal favorites of what I've done, mainly because of Lou's editorship, input and support.

Can you talk a little about your collaboration with Lydia Lunch, "Toxic Gumbo"? I didn't know much about Lunch back then, but it really felt like a good book for your sensibility -- but it also felt different from the books you wrote.

Lydia and I had been friends for years before that book. We'd spent some time talking about how since we both were creators, that we should do something together. And since I wasn't a spoken-word performer, me on a stage didn't seem like a good idea -- to me, at least. But her coming into my field, now that was a better possibility.

So, one day, we were walking down the street in New York, and I said I have an idea for a story that she should write. It's about a woman who has ingested so many chemicals, legal and otherwise, that her body has become a vessel filled with toxic bodily fluids. Lydia stopped walking, pauses, then turns to me, grinning, and said, "Her vagina can literally kill a man." And that was it. She went off and wrote the full script. As I started working on the layouts based off her plot outline, I suggested that we should make it a multi-media project, combining painted and traditionally colored comic pages, along with three-dimensional aspects, to fully utilize the medium. So, I had this fantastic artist, Maria D'Agostino, create these beautiful pieces that were then incorporated into the storyline. The end result is, in my humble opinion, exceptional.

It probably feels different, because the process creating "Toxic Gumbo," was unlike anything I had done, or have done since.

How did you get involved with "Superman: Metropolis," which was a really interesting Elseworlds book?

That's one of the stories I put in "Pencil Head" because it's just so damn ironically funny.

Mike Carlin, EIC of DC at the time, had previously said to me that I would never do anything with their Superman character. Then, some time later, he tells me about this script he's gotten, that adapts Fritz Lang's black and white masterpiece "Metropolis" using Superman's character lineup as the cast. He thought my style would be totally suited for it, especially if I hand-painted the entire book. And then came the "but you're only getting to do Superman for this one and only project." But my decision wasn't based on it being Superman, but because I'm a huge fan of that fantastic film. It was a chance for me to do something outside the norm. Plus, I got to draw those giant clocks, and steam piston machines, and that cityscape. Oh, hell yeah.

I liked the book, and after it did well, how did the idea develop to do more books that would combine DC superheroes with old films?

From what I know, the writers, Jean-Marc & Randy Lofficier, always intended it to be a trilogy. But when I first signed on, it was for only the "Metropolis" chapter. Then I heard afterwards that there was going to be a "Batman: Nosferatu" chapter. So, I definitely agreed to do that one. After that there was a long silence, until I got a call asking if I wanted to do a third installment, "Wonder Woman: The Blue Amazon."

Now, the only reason I agreed to do that book, was because they kept saying they wanted to collect all three into a trade, and the only way that was going to happen was if I did it. So I figured, why not? What a mistake that was, because none of it mattered anyway. DC's newly installed Editor in Grief, Dan DiDio, stepped into the vacating shoes of Mike Carlin, and took a huge ham-handed dump all over everything Mike had previously established, and "decided" not to collect the trilogy.

Anyway, I heard that Jean-Marc had even written a fourth, and final chapter, to that whole series. But, good ol' DiDio probably shot that down as well, because it never came to be.

Over the years you were drawing a lot of fill-in issues and short stories and different projects. Do you have any favorite experiences or projects among those?

Yeah, one in particular. I usually keep a page, or two, from every project I've ever done. Rarely do I keep the whole shebang. But the story I did for the "Mystic Hands of Dr. Strange" anthology, was one such project. All the other fill-in's were enjoyable, but that one in particular -- I won't part with a single page from.

You mentioned working really closely with two editors over the years, Lou Stathis and Archie Goodwin, both of whom died in the late '90s. I know a good editor can really make a difference, but is having an editor who knows your work and likes your work vital in terms of having a career, especially at a big publisher?

Well, it doesn't hurt.

I don't know if I'd say it's vital to having a career. I've worked for some editors that my work never really clicked with on a personal level. But even they had the sensibility to know that diversity in comics was vital to keeping the whole thing interesting. And so they'd hire whatever artist brought to the table something that was uniquely fitting for that specific project. And they would push it properly.

But, then again, if they knew your work, and liked it personally, what that did, for me anyway, was add fuel to creative fire. Which in turn made for a better end result. It also helps when they go to bat for you, that they personally like your work. For instance, Karen Berger green-lit two projects, "Black Orchid" and "Doom Patrol." For whatever reason, she felt that I should be the artist on "Black Orchid." Lou Stathis, knowing me so well, knew that me on "Black Orchid" would be a huge mistake. Of which, I completely agreed. And so, he fought to get me on "Doom Patrol," and eventually convinced Karen. That's the best example I can give as to the benefit of an editor liking your work and it's benefit.

Let's talk about working at Vertigo in the '90s, because I don't know if people appreciate what a creative and experimental place it could be. When Stathis was there he edited books by Peter Kuper, Terry LaBan, Ilya, Nancy Collins, Ed Brubaker, Eric Shanower -- just to name a few. I'm hard pressed to think of a comics company today that would publish that lineup of creators.

It truly was a glorious time to be working at Vertigo. When I had come over from Marvel/Epic, I still possessed that lingering enthusiasm of briefly working with Archie. And then, when I met with Karen, that same spark of anything-is-possible permeated from her. During the time I was there, it was like we were all sitting around throwing massive amounts of big sloppy plots against the walls. And whatever stuck, got done. Even the stuff that didn't stick, was fantastic, they just lacked that certain something. There were no limitations in coming up with new stories. In fact, Karen almost demanded new ideas be submitted on a regular basis. It was like a street court saying in playing basketball -- you can't make baskets, if you don't shoot the ball. So we made shots constantly. Some went in, while others missed.

Even if you were working on something at the time, and had something new in mind, she wanted to hear it. There was a period where I had two other green-lit projects, while I was still in the middle of working on the third. To put it simply, the work was there for the doing, all you had to do was want it bad enough to make it work. Karen hired Lou because he brought a sensibility of everything but comics. And with that, Lou had the freedom to recruit talent that came from outside the normal run-of-the-mill, and he ran with it until the wheels came off.

You've said that "Pencil Head" is your last comic. Is the plan still to collect the book? Will you be keeping your older books in print? Is there a chance that some of the books that have never been collected will finally get collected, and is there something that you think needs to be collected or completed?

Let me put it this way. Jim Valentino did me a solid by inviting me into Shadowline/Image. He first offered me the opportunity to collect my earlier works, "Transit," "Eddy Current," and "METROPoL," into beautifully bound hardcover, black and white editions, size based to my specifications.

He then asked me if I had anything new I'd like to do. With no demands, and no rules, he opened a door for me to create "Meta4," "Mondo," "Miniature Jesus," and "The Superannuated Man." All of which are some of my most personal, and satisfying projects to date. And then, he collected each one into a trade that reflected the individual series' specific tone, spot on.

For what's it's worth, Jim is one of the last few remaining people in the comics industry whose handshake holds more weight, than any contract I have ever signed. Jim gave me free rein to just let go, and create. For that, I am, and will always be, grateful.

That said, there is no plan for Shadowline/Image to collect "Pencil Head" into a trade. Now, I know they have their reasons why, but that doesn't take away my disappointment, or the fact that of all the series I've ever done, "Pencil Head" is probably the one series most deserving of being collected. Aside from all that, Shadowline will keep all the books I did with them, including all three library editions, in print, and readily available. But, from what I understand, once they sell out, I doubt there'll be a second printing of any of them.

As for any other books of mine that were never collected, I very much doubt that my "Doom Patrol," "Industrial Gothic," "Faith," "Junk Culture," and "Enginehead" series, will ever see the light of a trade anytime soon. That is, as long as Dictator in Chief DiDio is still in charge of making those decisions. And now that he's taken over Vertigo at DC, I can pretty much guess that it'll be a cold day in hell before he gives a green light to anything my name is attached to. Maybe one day, they'll boot his ass out of the company, and hire someone who actually knows what they're doing.

Maybe then, things will change. Maybe not.

Then again, they did just release "Industrial Gothic" digitally. So, who knows -- maybe the tide is turning.

You may be retiring from comics but you're not retiring from making art. Do you want to say a little about what you're doing and where people can find you?

Definitely not retiring from art. For me, that'd be like saying retiring from breathing.

I still love the idea of sequential art, and telling stories. But I've spent a lifetime doing those, and I just want to get back to being an artist that expresses himself through single images. Experimenting with ideas based on whatever strikes me at the time without the boundaries of a plot. So, I started painting these little 5" x 5" weirdo portraits of anything that worms its way into my head. The range of subjects is endless. And so, I'm just existing in this creative stream of consciousness. Moving from one character to the next. Some are from my creator-owned works, some are icons of products, cartoons, and/or other comics, and other characters that fall out of my head depending on whatever mood I might find myself in at the time. Which, usually, for me, is pretty far out there.

Anyway, if you want to see what I'm talking about, and purchase, head over to my store. Or, follow me on Twitter: @TedMcKeever, where I keep intermittent updates on what I'm up to.