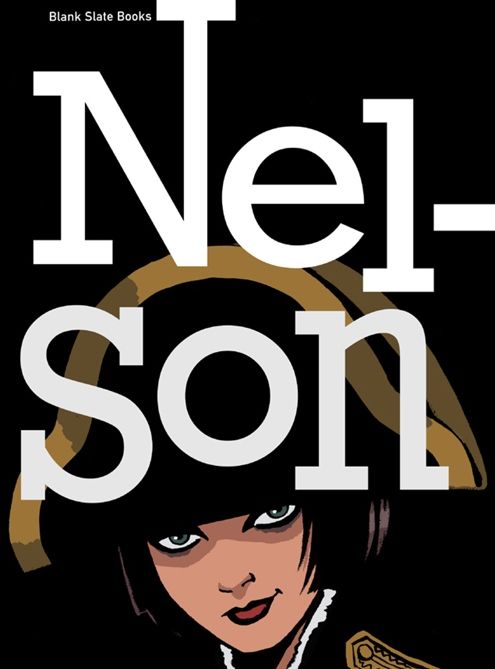

The concept behind Nelson is quite unique: A 43-year old tale about the life of Nel Baker, born in 1968, as told by 54 British creators, published by Blank Slate Books, in a 252-page collaborative graphic novel. (Is that enough numbers for you?) Did I mention that all profits from the book go to Shelter, the housing and homelessness charity? To mark the book's recent release, Woodrow Phoenix (who co-edited the project with Rob Davis) took the time for a recent email interview. Once you've read this interview, be sure to enjoy CBR's Mark Caldwell's interview with Davis, as well as CSBG's Greg Burgas explaining why he ranked this book as one of his best graphic novels of 2011.

Tim O'Shea: In the afterword for this book, you noted that there is "an invisible jigsaw in this book that you could put together if you knew where to look for the pieces. A secret history, a kind of group autobiography, comprised of memories and reflections from each of the creators of Nelson." Did you always see the jigsaw pieces, or did the pieces reveal themselves to you as you compiled the book?

Woodrow Phoenix: Those pieces gradually made themselves apparent as we put the book together, really. Because the idea with the story was to ground it in recent history through the eyes of Nel, our protagonist, many of us used bits of our own lives. Things that we remembered, that we had seen or been told about, personal family history or items that had been in the news at the time. We based our stories on them or did ‘what if’ fictional riffs with them and Nel. You’ll notice a lot of real events are alluded to in the backgrounds of strips. There are a lot of pop music references, for instance. Before the late-1980s and cable & satellite TV, songs that were in the charts were the only music you’d hear on local or national radio and everybody had to listen to the same three or four stations because that was all there was. So they are a really good indicator of moods and styles in 1970s and 80s Britain, and most people used them for texture in their stories.

As the book progressed we saw what a good narrative engine the episodic chapter idea was. Because you could build an event into a story without having to explain what happened before or after it, creators could start anywhere. But they could ‘comment’ in their chapters on events that were significant to them from previous chapters. So by the time we got to the end I’d found out a lot of fascinating things about my fellow contributors!

O'Shea: Speaking of the book, you are one of its co-editors. How did the co-editing duties break down (who did what?) in terms of the collaborative editing of the book?

Phoenix: We shared the story editing equally, talking through every decision before we asked anyone to change anything. We asked everyone to follow the same process: read the story so far, then deliver an outline or script within three days. Rob and I would read and discuss it, then one of us would give the creator any notes or feedback necessary. They had another three days to come back with rough layouts which we would again discuss and comment on. Once we’d okayed them, the script and roughs were passed onto the next person in line to start them working. This way people could work on their final finished pages without feeling pressured to hurry, but the book kept moving, a chapter a week.

I had the extra responsibility of the design and production too. One of the main problems with anthologies is how the differing styles of many artists can easily make a book feel random and unfocused. So I knew a page design that framed all the artwork in the same way was going to be crucial to tie everything together. The running heads and no top or bottom bleeds give a consistency that makes Nelson feel directed and curated; no matter what’s going on within the page it’s all visually and thematically connected.

We were determined to make this book accessible to people who had never read a comic before. People new to comics struggle with figuring out reading order and what to look at first. So the other key thing I did to help consistency was to go over everyone’s lettering and balloon placements, making sure that all the creators were using the same “visual grammar” even if their styles weren’t remotely similar. Lettering is often the most neglected part of comics but speech balloons are the way that people connect with your narrative. Bad lettering will confuse and annoy your readers and destroy your comic. So it’s crucial to do it systematically and logically; even moreso on a large project like this. I did a lot of tweaking.

O'Shea: How did it come to be that certain creators landed certain years in the project, were they selected because "Hey creator A's style is best suited for that year." Or what was the criteria?

Phoenix: Some people really wanted a particular year, so they got it - but mostly it was about fitting styles to a time period, and putting the right people next to each other to get the most interesting transitions going. Rob had a idea of what style would fit a particular time in Nel’s life–childhood, teens, early adulthood, etc–and he decided who should go where. There was a little shuffling later on but 70-80% of the creators were happy with their position in the lineup and as you can see, the progression worked out really well.

O'Shea: I am not going to ask you for favorites, of course, but can you mention a few contributions that were far different than what your expectations were for a particular creator?

Phoenix: Almost no-one did what I expected they would. We picked people who wrote or wanted to write as well as draw. Few of us did literary naturalism, so it was definitely going to be pushing most contributors into new territory. Jamie Smart surprised me with the depth of his characterisation of Nel and her parents in just two pages for 1971. He managed to get so much personality and quirkiness into them so deftly and economically, it was an amazing gift to the book right at the beginning. There’s a three panel sequence in Sean Longcroft’s 1975 chapter that is just breathtaking in its appallingly casual depiction of a near tragedy. I keep going back to it. John Allison did some beautifully subtle character studies with just enough slapstick to throw you off the scent. Simone Lia captured the random madness of teenage (il)logic wonderfully well… I could go on. Nelson is packed with great moments.

O'Shea: In editing these various creators, were there any storytelling lessons you took away from the experience?

Phoenix: It’s a strange (but very telling) quirk of the industry that generally comics editors are not artists. They come from print media, publishing or even TV backgrounds and it isn’t considered important or relevant for them to know anything about drawing. I discovered that when I gave very specific art notes to creators–move this character up and put the speech balloon over here so that in the next panel your eye will go here, break this action into two panels, this should be an up-shot, move the horizon line down in this panel, etc–they were usually amazed and delighted to get storytelling advice that made sense and fixed narrative problems that they might have been stuck on. One person said that the total amount of useful, targeted feedback he had received in twenty years of drawing comics was less than he got from Rob and I in two weeks.

Rob and I have opinions and we aren’t shy about voicing them, which is the main reason why we did Nelson, to make a book that we thought needed making. But as a result of working with 53 people on this book and listening to what they have to say I think the low standard of basic narrative skills in comics and graphic novels today is due to inadequate editing as much as to artists having to learn as they work, with nobody correcting their storytelling problems or fixing odd tics and habits.

O'Shea: Any chance if response is strong enough, would you be willing to embark on a book of this scope and logistics again?

Phoenix: I really don’t know if I would do this again because it was hugely demanding both technically and emotionally. I had to keep the overall structure of the book in my head so that I could see where each story fit or didn’t fit Nel’s evolving narrative; that was easy for a while but thirty chapters in, the number of events and character arcs to remember were immense. I had to tell people their ideas didn’t work and deal with the fallout, which was sometimes sheer misery. Chasing copy, explaining rewrites, making suggestions and ensuring everyone was happy with what they ended up submitting. I had to juggle deadlines and corrections and check everything fit the design templates. There were some weeks where it left no time for anything else. Combine all that with the stress of living with a big cloud of uncertainty over my head about whether it was all going to fall apart in a huge embarrassing mess before we got to the end. My girlfriend Bridget deserves many fine dinners for proofing the final pages and helping me pull it all together.

O'Shea: What were the most challenging logistics of co-editing a project of this scope?

Phoenix: We were doing this by telephone and email; sometimes it took days to co-ordinate our responses and valuable creative heat would begin to cool before Rob and I could discuss a script. Luckily there were only five or six occasions where we didn’t see eye-to-eye, but when we didn’t we talked it through until one of us convinced the other or found an alternate idea that we could agree on. We rejected a story outline for one of three reasons:

a: it had already been done

b: it was too closed and didn’t give the next person anywhere to take it

c: it didn’t make sense

It was sometimes very tough to tell people to try again, which was mostly my job, for some reason… Some contributors who weren’t used to working with an editor did not take criticism well and that meant difficult emails or strained phone calls to make them understand it wasn’t personal. But once they saw that it was about technique or logical narrative flow and not anything to do with my (or Rob’s) own likes or dislikes, most people were okay with making changes. The book went along paths that I would never have chosen were I the sole writer, but collaboration is embracing what other people come up with and making it work. Whether you like it or not is irrelevant. You just have to find the logical departure point and take it where it should go next.

O'Shea: Had you always intended the book to be published by Blank Slate, or had you considered others? If not, what is it about Blank Slate that made you want to have the book produced and released through them?

Phoenix: Blank Slate Books was central to making this book a reality. Rob and Kenny Penman, of Blank Slate, had been talking about doing a book together. When Kenny saw the initial discussion Rob and I were having about the 'collaborative graphic novel' project he offered to publish it if we were serious about it. That transformed our really cool idea into a potential book and suddenly we had no excuse not to go ahead with it. We did some quick calculations and I ran the specifications past Kenny, he was supportive and positive and enthusiastic, and just like that, we had a book to put together! By the time we had our first production meeting in January we were already five chapters in. I’m really grateful to him for being such a calm, no-nonsense, straightforward person to deal with. He saw the possibilities for something new and gave us the opportunity to create it, he trusted us to deliver it and hardly asked us to change a thing. We couldn’t have found a better person to work with.

O'Shea: How did you all first find out about Shelter? Were the charity folks surprised to find out you wanted to do a book to benefit them?

Phoenix: They were very surprised. It was Kenny’s idea to donate the profits from the first printing to Shelter and we thought it was an excellent idea. Housing in Britain is so expensive and so tilted in favour of haves vs have-nots that most of us are only a few pay-checks away from being out on the street. Nelson is not really a ‘charity book’ though - it’s a book that is also benefitting a charity, if you see what I mean. There would have been no difference in the content wherever the money went.

O'Shea: You wrote of your contribution to the book "And because my sister died decades ago, but I still think about what our lives would be like if she had lived." Was it cathartic on some level to delve into a piece that partially delved into your personal loss?

Phoenix: I’m not sure if cathartic is quite the right word. But maybe, yes. It felt like a good, important thing to introduce as a theme because we don’t have very effective mechanisms for coping with death as a society, especially the death of a child, and the lack of ways to acknowledge and deal with that loss makes bereaved people go a little nutty. It happens all the time and mostly we try and forget about it as quickly as possible, ignoring that the people it happens to are never the same again. My family went off the rails for a while in the face of that grief, though we knitted back together eventually. A couple of my friends whose children died had similarly bleak experiences.

I was surprised by the alacrity with which Sonny’s death was seized on by the other creators, actually. I had expected everyone to avoid dealing with it in favour of easier topics, but it became a dominant subplot right from the beginning. So that showed me my instincts were correct: there really isn’t such a thing as an undiscussable topic. It just comes down to how you present them.We’re all curious about how other people live, how they cope, how they feel. We only need the permission to ask the questions and we’ll be digging right in there.