Stuart Moore is a writer I've known and interviewed for a number of years. In the past, we've typically focused on near-term/upcoming project discussions in our interviews. But more recently, for nearly a year, he and I have been working on a series of email interviews trying to cover the scope of his career to date. This process started in mid-2009. Moore and I realized earlier this summer it would be best to get this interview finalized on the eve of Namor: The First Mutant 1's release (which comes out from Marvel this Wednesday, August 25) . My thanks to Stuart for his time and patience on this fun and hopefully thorough examination of his work. The first installment of this two-part interview will focus upon his work as an editor. Tomorrow, in our second part, we will focus on his freelance writing. (My thanks also to fellow Robot 6er Tom Bondurant for giving me some feedback on the early stages of this interview and suggesting a question of his own.)

Tim O’Shea: You got your start at St. Martin's Press, back in the mid-1980s, how did you get that job?

Stuart Moore: I graduated from college, not sure of what I wanted to do. Spent the summer in California, then came back east and started looking for a job. Book publishing at that point was very partial to Ivy League graduates -- probably still is -- so I got the referral through Princeton's career services center. I worked for about 2 ½ years as assistant to a brilliant woman who edited craft guides, child care titles, and etiquette books. It wasn't exactly my field, but to this day I still know that you say “Congratulations” to a groom and “Best wishes” to the bride.

O’Shea: While at St. Martin's, you edited a variety of science fiction, mysteries, pop culture nonfiction projects--as well as a few comics-related titles, such as Ron Goulart's THE GREAT COMIC BOOK ARTISTS. The book covered around 60 artists, some of them fairly obscure--did you find yourself learning a great deal while editing it? For example, a search of the name "Dirk Briefer" turns up nothing on the Internet, but apparently he warranted a mention in Goulart's book. Talk about what you recall of that editing work (and please toss me a bone and tell me who Briefer was?

Moore: Ha! It's Dick Briefer -- try running the search again. He's best known for a run of Frankenstein strips, some of which were serious and some comical.

I learned a bit, yes. But I already followed the comics field closely, and back then it was a lot smaller. You could keep up with everything much more easily.

O’Shea: As a kid, I fondly remember reading the late Jeff MacNelly's SHOE comic strip (no really, I own 1978's The First Shoe Book and 1980's The Other Show). So to find out you edited a SHOE collection while at St. Martin's caught my attention. Did you get to work directly with MacNelly on the project. In compiling the collection, were you working directly from his originals?

Moore: I did two or three SHOE books, actually -- maybe four. No, I barely dealt with Jeff MacNelly at all; everything went through the syndicate, and they provided stats of the strips. I had one or two very nice phone conversations with him, but I got the impression he was happy enough to let the syndicate handle the book collections. The fun part of those books was choosing the strips and the titles. Everyone liked TOO OLD FOR SUMMER CAMP AND TOO YOUNG TO RETIRE, which was taken directly from one of the strips. I think I still have a promotional t-shirt with that phrase on it.

O’Shea: Another project you worked on while at St. Martin's was a large Dick Tracy compilation spanning the strip's history, what are your recollections from that effort?

Moore: That was a great book -- Max Allan Collins was terrific to work with -- but a hell of a lot of work. In a way, it was typical of what I did at that company; I had a small budget, so I had to jump on trends and projects before other people noticed them, and acquire the books as cheaply as I could. In this case, the Dick Tracy film was coming up, and it was positioned as the summer's big movie. There were all kinds of direct tie-ins in the works, but no one had put together a big collection of the strip for many years. I already had a relationship with the syndicate, so I pounced on it.

Unfortunately, the syndicate's proofs were of very spotty quality. The early '60s material was particularly weak; it looked like it had been shot with a Polaroid from across the room. I learned how to work an old stat machine specifically in order to clean up those proofs, because we didn't have a comics-style production department and I couldn't ask the art department to spend a whole weekend doing it. (This is all pre-Photoshop, of course.) I did the best I could, and came home smelling of chemicals. But I was learning as I went, so that section of the book still doesn't look too great.

I also did a preliminary design on the book, suggesting visual “running heads” showing head-shots of the villain of each story. I still like those. Ultimately, the film didn't do terribly well, but the book still sold well enough that they published a sequel after I left.

O’Shea: After St. Martin's, in 1990, you joined the editorial group that became Vertigo two years later. Before getting into your Vertigo years, can you talk about the period leading up to Vertigo?

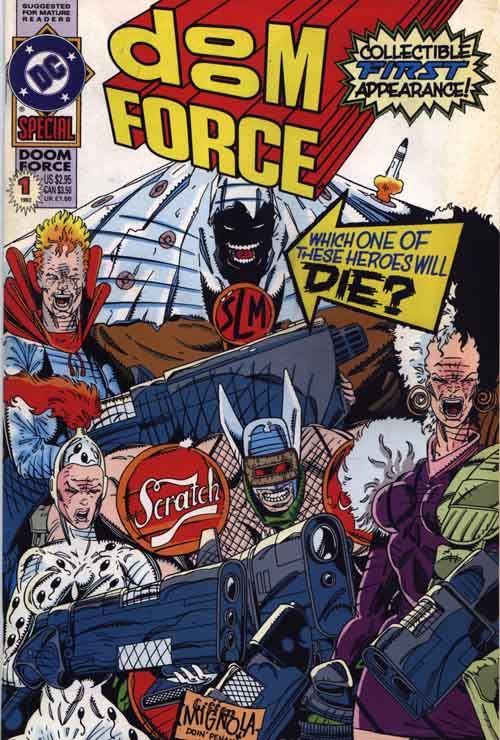

Moore: It was exciting and a bit chaotic. I'd been hired to work in Karen Berger's group, which handled SWAMP THING, HELLBLAZER, SANDMAN, DOOM PATROL, ANIMAL MAN, and they'd just launched Pete Milligan's SHADE around the time I started. But we also did some superhero titles, too. The lines weren't as firmly drawn as they became when we launched Vertigo, which gave us room to do something like Bill Loebs's DOCTOR FATE or Grant Morrison's DOOM FORCE.

During that time, I hired Garth Ennis to write HELLBLAZER and Nancy Collins for SWAMP THING. The job was a big change for me; I had less autonomy than I'd had as a book editor, but more prestige and a better budget. I immediately took to the comics community...I've always loved the people. I know that sounds stupid, but it's true.

O’Shea: How hard was it to get DC to approve Doom Force, a satire of Rob Liefeld's/Image style storytelling? Were you involved in recruiting the line-up of artists on the satire, which included Walt Simonson and a cover by Keith Giffen and Mike Mignola?

Moore: DOOM FORCE was Tom Peyer's baby, as editor. Tom and I came up with the title at lunch one day, while playing a silly game of putting together tough-sounding words to form comic book titles (a popular sport of the day -- remember FORCE WORKS?). Tom called Grant, who jumped all over it. I might be wrong about this, but as I remember, Keith Giffen came up with the cover gag -- a blurb reading WHICH OF THESE CHARACTERS WILL DIE? in an arrow pointing, very clearly, to one particular character.

[In sharing the initial email exchange with my fellow Robot 6ers, Tom Bondurant had the following question] Bondurant: Of the titles you mentioned [SWAMP THING, SANDMAN, etc.], Bill Loebs' DOCTOR FATE (drawn mostly by Peter Gross, I think) sounds like the most conventional superhero title. I know you had to deal with at least one big crossover (WAR OF THE GODS), but otherwise how free were you to do what you wanted?

Moore: That book was handed to me right when I first started at DC, and I had a pretty free hand. WAR OF THE GODS was coming out of our editorial offices, so that wasn't too hard to coordinate. Bill and I worked most of it out between us.

DOCTOR FATE was one of those titles that never sold big, but people still mention it to me from time to time. It was a pretty charming book, I think.

O’Shea: On to Vertigo, you edited a slew of books, including PREACHER, HELLBLAZER, SWAMP THING, THE INVISIBLES, BOOKS OF MAGIC, JONAH HEX. Which one should we discuss first--and then just go down the line with your recollections.

Moore: SWAMP THING had suffered a wrenching shift when Rick Veitch resigned over content issues, just as he was building up to the conclusion of his run. When I came on, there was a creative team that wasn't quite working out. Karen Berger had been editing the title for a long time, and decided it was time for another editor to see what he could do with it. I brought Nancy Collins on and we managed to revitalize it, enough to stabilize the book. Later on, Mark Millar and Phil Hester took over, and that was a little wilder, more chaotic and fun.

HELLBLAZER: Jamie Delano was just leaving the title after forty issues or so, and I was handed that one too. Garth Ennis, who was quite young at the time, had written an inventory issue for Karen, which got folded into his initial plotline and became the second part of "Dangerous Habits." He was the obvious choice. Will Simpson drew the book for a while, with some fill-ins, and then Steve Dillon took over and that team really gelled.

JONAH HEX was a bit of a game-changer in a couple of ways. I think it really shifted Vertigo in a "men's fiction" direction, for want of a better phrase, away from the fantasy/horror that had dominated it up till that point. That led, in turn, to books like PREACHER and 100 BULLETS. Joe Lansdale and Tim Truman were a great team, and Sam Glanzman's inking was gorgeous too...it all came together, with the painted color. I was on-the-ball enough, early on, to realize that the pacing of this book would require more than 22-24 pages per issue, so I ran numbers and got the first two minis published in a no-ads 32-page format. I had a big hand in designing that book, too.

BOOKS OF MAGIC: Neil Gaiman's miniseries was enough of a hit that we wanted to do something more with the Tim Hunter character. We poked around with it for a little while and finally introduced the character in the CHILDREN'S CRUSADE event, which had its flaws but also produced some nice work. I edited the start of the ongoing series and then passed the editorial duties to Julie Rottenberg, who's now an acclaimed TV writer. I came back to it as John Rieber was wrapping up his run, and pushed for Peter Gross, the artist, to take over as writer too.

THE INVISIBLES was positioned as Vertigo's next big title; I think everyone was getting a little nervous because the end of SANDMAN was in sight. You have to realize that no major American comics company had ever had an imprint like this, where a good deal of the material was creator-owned and most of the franchises were built to end at a finite point. That makes projections difficult -- you can't just say "Well, we'll have sixty issues of assorted Superman titles out next year, and they'll sell a rough minimum of X copies apiece." You have to keep starting over.

So we poured a lot into the launch of THE INVISIBLES. I'm glad we did, and I think I still have a pink hand grenade wall-cling around someplace. But in retrospect, I don't think the book was built for that. It was brilliant, eclectic, and required a lot from the reader. Grant can pack the room with something like JLA or FINAL CRISIS, but INVISIBLES was more of a refined taste. His proposal for it, incidentally, was sheer genius.

O’Shea: What was it about Morrison's Invisibles proposal that made it sheer genius?

Moore: He analyzed superhero comics, Vertigo/Sandman, and what he wanted to do in comics all in one brilliant introductory page, then told you exactly how INVISIBLES was going to work. It was very funny, too.

PREACHER was Garth and Steve's followup to HELLBLAZER -- they went straight from one to the other. I always knew it would be a hit. I edited the first year and then passed it along, because I was starting the Helix imprint and because the book honestly didn't need me...those guys knew exactly what they were doing. When it became a success, PREACHER really wrenched the focus of Vertigo away from SANDMAN-style dark fantasy, for a while at least. I purely love PREACHER...every page, every panel. When I left DC, it was the first book I'd buy at the comic shop.

O’Shea: How important was Preacher in showing the corporate parents that Vertigo was an important imprint beyond Sandman?

Moore: Well, DC already knew the imprint was important. Books like HELLBLAZER, SHADE, and SWAMP THING all had their followings, and sold reasonably well. The trick was to find a flagship title, a book that sold better and had a higher profile than the others -- like FABLES does today -- and PREACHER pulled that off. I can't really speak to what the higher-ups at Time Warner thought of it all; we were fairly isolated from that.

O’Shea: How hard or easy is it to edit a strong writer, like a Grant Morrison or Garth Ennis?

Moore: You develop relationships. It really helps if people trust you, which is a mixture of (a) liking the work you've done and (b) knowing you're not lying to them. It sounds simple, and in a way it is. But then you have to follow up and make sure the end product all comes together.

As far as strong writers: You look at every situation and decide whether you're going to do more harm than good by jumping in. I barely edited a line of THE INVISIBLES, because the whole thing was like a giant fractal hyperspace crystal or something -- throwaway lines of dialogue would recur, with greater meaning, two years later. If you pulled out a straw, the whole house might come down. But I've worked with a lot of creative teams, and everybody's different. You feel things out, you step in when you think it's important, and don't act like a dictator. My training in book publishing helped with that.

O’Shea: Can you tell me the origin of the Helix, the DC Comics imprint that ran from 1996 to 1998?

Moore: DC Publisher Paul Levitz had wanted a science fiction imprint for some time. I originally pitched something oriented around a high-profile licensed property -- sorry, I can't say what it was -- but that was too expensive and difficult to get. It probably would have been a better commercial hook, though, with original properties launched around it.

I really didn't see the point of using Space Cabby and Ultraa the Multi-Alien; the DC space characters are fun, but they're mostly kind of silly and I didn't see them having any huge following, with the exception of Adam Strange, who wasn’t available, as I recall. So we went with all original properties, which was more interesting to me, but which made it a tough sell.

O’Shea: The imprint lasted two years, but I'm curious--at the outset, was the plan "we'll give this a two-year trial run"?

Moore: No, it wasn't that sharply defined. I kept asking if they wanted to keep it going, and they did, until they didn't.

O’Shea: All the titles ended, with the exception of Warren Ellis' Transmetropolitan, which was folded into the Vertigo line. What hamstrung success for the various titles, in your opinion?

Moore: Well, like I said, an imprint without any ties to existing properties or franchises is always a hard sell. You have to remember, too, that most of the Helix projects were miniseries, which ran their course and then ended.

The market was also in a period of contraction at that time, following the speculator boom. Stores were hurting a bit -- they were ordering pretty conservatively. I remember a DC marketing exec saying to me, "I think we should wait until the market is healthier." I didn't say this aloud, but I thought, "That's going to be a while." And I was right. In the end, we just rolled the dice and launched the line.

A lot of the initial books were dark in tone, too, which made the imprint look a little too similar to Vertigo. That was mostly an accident of scheduling. More adventure-oriented titles, like Chris Moeller's SHEVA'S WAR, just took longer to produce.

A larger point, though: Pure science fiction has always been a hard sell in comics, for whatever reason. Even back in the EC days, horror books sharply outsold the sf titles. I don't know exactly why that is, and I don't think it's an insurmountable barrier, but so far it's always held true.

O’Shea: Of the titles that were created, after Transmetropolitan, would you say Gemini Blood was the most successful series from the imprint or does that designation belong to another Helix series?

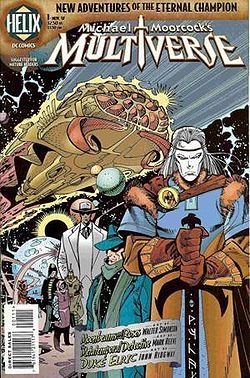

Moore: Well, Garth Ennis's BLOODY MARY probably sold best. MICHAEL MOORCOCK'S MULTIVERSE had the benefit of his fan base, though a lot of people found it confusing. I loved it, but I understood the mixed response. I thought people would just get into it and let it flow over them, the way people used to read HEAVY METAL, especially with Walter Simonson's trippy art on the lead feature. But I neglected to consider the one big factor in HEAVY METAL's success: nudity. (MULTIVERSE does feature Walter's first and, as far as I know, only portrayal of a topless woman, however. And it's very nice.)

What were we talking about again?

O’Shea: Did you take some level of Helix-related pride when Transmetropolitan was included in the DC's 'After Watchmen, What's Next?' promotion?

Moore: Sure, I love TRANSMET. The character was just terrific -- appalling and inspiring at the same time -- and at the beginning especially, Warren and Darick were really in sync. Issue #8 is one of the best comics I ever edited.

O’Shea: Can you recall what made #8 such a great issue to edit?

Moore: There wasn’t much editing involved! The script came in, and it was beautiful, just a gorgeous character portrait melded to a real science fiction background. The art raised it to an even higher level...the result was just heartbreaking, sad and funny and perfect.

I’ve always said that, as an editor, if something comes in that doesn’t need work, you should leave it alone. That way you get to go home early AND everyone thinks you’re a genius.

O’Shea: Can you break down what you did editorially between the end of Helix and your transition to Marvel Knights in 2000?

Moore: I went back to Vertigo for a while, taking over BOOKS OF MAGIC again when Julie Rottenberg left staff. I edited some other things there, like THE TRENCHCOAT BRIGADE, a pretty nice miniseries that unfortunately never got collected because of the wholly coincidental appearance of Columbine's Trenchcoat Mafia. Some pretty bad luck there.

In summer 1999, I left DC. I'd been there for nine years and I was a bit burned out. For the next year, I worked for a bit on a startup dot-com comics venture that never went anywhere and did some assorted freelance writing.

O’Shea: How did you end up deciding to transition over to the Marvel Knights team?

Moore: Joe Quesada approached me; I think Richard Starkings and a few other people, Mark Millar maybe, had recommended me. Axel Alonso was moving over from Vertigo at the same time. He and I are friends, and we talked about the situation a lot. It was a pretty amazing opportunity...Marvel really wanted to turn everything upside down, and the Marvel Knights office at the time operated very independently. I worked in the office four days a week and was free to write for other people, which is incredibly rare in this business. And Marvel Knights itself was a really exhilarating experience. I owe both Joe and Nanci Quesada a lot for that opportunity.

O’Shea: What did you consider to be your best editorially efforts while on the Marvel Knights books?

Moore: Bendis's ALIAS and DAREDEVIL, for sure. ELEKTRA was a tricky one, but both Brian and Greg Rucka did some nice work on it. Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon's PUNISHER. We edited so many books in such a short span of time that it's hard to remember. There was a short story by Garth and Joe Q, where the Punisher took down a sadistic dentist, that was a hell of a lot of fun.

O’Shea: You edited Captain America, a property that must have been a challenge to editorially guide in a post-9/11 climate. Did real world events make editing the fictional adventures of that nature more problematic?

Moore: Short answer: Yes. After 9/11, we postponed our planned launch story and started from scratch. The result was a very powerful first issue -- John Rieber poured his heart into it, and John Cassaday's Ground Zero stuff was really wrenching -- but ultimately we had a little trouble structuring the book after that. CAP was the only title I felt bad about leaving, because the stories still needed a lot of shaping after all the shifting around we did.

O’Shea: Looking back at the number of successful titles that you have edited over the years, and seeing the winning combination numerous times that have led to strong runs--can you think of any titles that it still mystifies you why they were not a bigger success?

Moore: My tastes can be odd...one of my all-time favorite books I edited was VERMILLION #8, by Lucius Shepard and John Totleben, a beautiful, lyrical, self-contained story that very few people read. I'd hoped the HOWARD THE DUCK revival would sell better, too; I absolutely love the final issue of that, where Howard talks to God and finally comes to some sort of peace about his life. But so many factors go into the success or failure of a title...you can't blame yourself when something just doesn't hit. Obviously popular characters are a big draw, and a new series either gains momentum right off or it doesn't -- you get very few second chances in the direct market. You just have to move forward.

O’Shea: When did you first get the itch to want to pursue a freelance writing career?

Moore: Age four? Seriously: I've always had writing projects on the side, but I wasn't really confident about it for a long time. Toward the end of my time at Vertigo, I started thinking about it, but DC wasn't structured well for editors to write (which I completely understood). In order to make it work, I had to take a leap and leave my editorial career. Which has turned out to be absolutely the right thing to do.