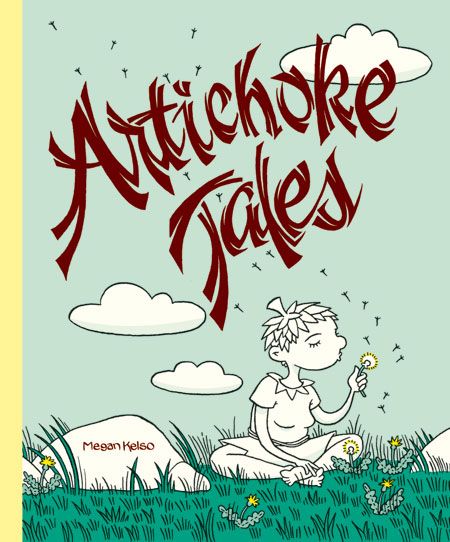

What does it take to make a story just right for some creators? As revealed in this interview with Megan Kelso, with her latest book, Artichoke Tales (released by Fantagraphics a few months ago and praised by Brigid just yesterday)--it took 10 years. Not every storyteller takes the time to indulge my questions in the manner that Kelso did, an effort for which I'm extremely grateful. Here's the scoop on the book: "Artichoke Tales is a coming-of-age story about a young girl named Brigitte whose family is caught between the two warring sides of a civil war, a graphic novel that takes place in a world that echoes our own, but whose people have artichoke leaves instead of hair. Influenced in equal parts by Little House on the Prairie, The Thorn Birds, Dharma Bums, and Cold Mountain, Kelso weaves a moving story about family amidst war. Kelso’s visual storytelling, uniquely combining delicate linework with rhythmic, musical page compositions, creates a dramatic tension between intimate, ruminative character studies and the unflinching depiction of the consequences of war and carnage, lending cohesion and resonance to a generational epic. This is Kelso’s first new work in four years; the widespread critical reception of her previous work makes Artichoke Tales one of the most eagerly anticipated graphic novels of 2010." Fun aside, in clarifying a detail about this interview, I learned that Kelso created a iGoogle theme, which can be accessed here. One last item, Fantagraphics posted a 16-page preview here.

Tim O'Shea: Creating Artichoke Tales represented more than six years of your creative life--can you describe how relieving (or what emotion you felt) when you finished the tale?

Megan Kelso: Truth be told, it was more like a ten year project. I think for some reason my publisher wanted to down play how friggin' long it took me to finish this book. It was very protracted because I took a lot of breaks to do other things; freelance work, a wedding, moving, having a baby, moving again. I actually finished pencilling the last two chapters in 2005, which is really the heart of the creative work. I pushed myself on that because I wanted to be done with the storytelling part of it before I was pregnant. But then the final denoument, the inking, the computer shading, the corrections - I didn't begin that work until two and a half years later. It was kind of excruciating doing all the final work on the book after it had been completely drawn - I think because the urgency and excitement of getting the story out was over. Then it was just drudge work. I finally finished all the work just before Thanksgiving of 2009 and I was 100% thrilled and happy about it for months. The let-down, "nothing left but doubt" part of finishing a huge project did not set in until I recently saw it in printed form. I am totally happy with how the printing and production came out, but even still, there's a bit of a void. I think I'm fending off a bit of a mid-life crisis.

O'Shea: On page 24, as the two characters are intimate, I was curious at your use of candlelight to convey the scene in silhouette--is that how you had always viewed that scene or did you have a few failed drafts before settling on that manner of executing it?

Kelso: I think this is pretty much how I pictured the scene in my head. I did a lot of backpacking as a kid, and always loved the shadow-play effect that a camping tent lit from within has. Of course in reality you would never see such crisp silhouettes. When it came time to do the shading though, I do remember re-doing that a bunch of times. What looks good, what is realistic, and what is clean and simple are not always the same thing with shading!

O'Shea: Rather than opting for black and white or full color, the book is done in a light blue-greenish tone, how did you arrive at that look for the pages?

Kelso: Artichoke Tales started as a black and white minicomic in 1999 with very minimal gray shading. But long about chapter 3, some colleagues who I respect a lot started suggesting that it would be awesome if Artichoke Tales would be in full color. Color printing was getting cheaper and cheaper, and I had started doing more color work for various anthologies and magazines, so I started experimenting with the idea of coloring it. I tried a lot of different palettes and approaches and really agonized over it, but I couldn't find a color scheme that I thought really worked and gave the world the look that I had in my mind. But once the idea of color for Artichoke Tales was in my head, it was hard to go back to accepting black and white. I have been very influenced design-wise by Tom Devlin and Jordan Crane who have used a lot of single pantone colors for printing black and white stories. Tom Devlin and Brian Ralph did Brian's book "Cave In" that way. Jordan did Non #5 that way. So after giving up on the full color idea, I hit upon their method of using one pantone color with a couple different percentages of shading. It was a little nerve wracking picking the color, but I got a lot of advice and support from Jordan Crane and Jacob Covey, who is the book's designer at Fantagraphics.

O'Shea: Was the story always going to be about three generations or did it grow to three generations as you worked on it?

Kelso: The original plan was a three chapter story, but as I started thumbnailing those first three chapters, things quickly got more complicated, and I realized I needed to have 6 chapters in order to have this symmetrical structure I wanted of 1.present day, 2.old history, 3.recent history, 4.recent history, 5.old history, 6.present day. So that structure of three generations, 6 chapters was in place before I completed the first chapter. Though the structure was in place early, the specifics of the family tree and the events changed quite dramatically over time.

O'Shea: While the book is able to cover a great deal of ground, literally and figuratively, were there aspects that you had to leave out to allow the overall story to breathe?

Kelso: I puzzled over the family members quite a lot. There were some aunts, uncles and siblings that got jettisoned. It was challenging to strike a balance between having a family that was populated enough to seem like a real family, but not so big that it would be impossible to keep the characters straight. I was further handicapped by choosing to have everyone have the same hairdo! It never really dawned on me until I was well into Artichoke Tales that hairdos are the major signifier that cartoonists use to distinguish different characters from each other. I also had a lot more information in the "old history" chapters about the Queen that I wound up not using, because I didn't want to get into that whole Lord of the RIngs thing where Tolkien had all these appendices to add in the extra backstories he'd invented. I didn't want the book to be overly dominated by the backstory.

O'Shea: I expect you have an affinity for all the characters in the story, but as you juggled the various players over time, did any of them grow on you more as you went along--and in fact grew (in character dynamics) beyond your initial intent?

Kelso: Definitely. Dorian is the best example. He started out as a peripheral character, and then eventually became Brigitte's father. It was one of those situations where it felt like he asserted himself independently of my plan for him. And I liked him, so he got a bigger role. In fact, the only significant re-drawing I did after finishing the book was in Chapter 1, because that was done before I knew Dorian was Brigitte's father. I had to go back and re-draw him so the difference in their ages was more apparent.

O'Shea: In building the artichoke world and the Quicksand family, how did you arrive on those aspects--why make it an artichoke world, as opposed to say a celery world? This is not meant in jest, I'm genuinely curious.

Kelso: The artichoke people started as a casual doodle. I think I was riffing on The Jolly Green Giant's sidekick, Sprout. So I just started drawing these people whenever I was on the telephone, or just playing around in my sketchbook. The more I drew them, the more ideas I had about their world, and I just slowly started to build a story about them. This was the first time since starting to make comics, that I generated a story from a drawing rather than from an idea, or from something I'd written. It was excitng to me because it seemed more like "pure comics" to me, coming from a drawing. I think it was the beginning of me taking a more intuitive approach to coming up with stories, rather than nailing it all down ahead of time with a script. I think for that reason the artichoke people have a special place in my heart because they came to me in this rather mysterious muse-like way, rather than the more cerebral, "I want to do a story about X" way, which was how I'd worked before. The first artichoke story was called "Pennyroyal Tea" and it ran in my comic book Girlhero #5 in 1995 I think. After I did that story, I just knew I wasn't done with them. The short story suggested a larger world to me. In 1996, I roughed out a 3 chapter story that was kind of the skeleton of Artichoke Tales. I set it aside for awhile to finish the last issue of Girlhero, and then to do some stories for my first book collection Queen of the Black Black, and a 24-page educational comic about recycling. I didn't take up Artichoke Tales again until 1999 - and by then, I decided it was an even longer story, and expanded the roughs to the 6 chapter structure. I got to work on it in earnest in the spring of 2000. I finished the first chapter by the end of the year, but I didn't put it out as a minicomic until 2001.

O'Shea: As an afterword in the book, you explain that "'Place' is not a character in this book.I dislike that conceit." There's a passion to those two lines that surprised me (but given the quality and nature of your work, I should not have been surprised [that is a compliment]). Why do you so passionately "dislike that conceit"?

Kelso: I dislike the conceit that place can be a character because I think its reductive and human-centric. Places are hard, unforgiving, unfeeling, kind of the opposite of human attributes - that is especially apparent in wild, harsh places like mountains and oceans. They don't have feelings or personalities. They can be beautiful and sweet, but also violent, destructive and fatal. It is all completely amoral; the beautiful landscapes are not here to reward us, nor do natural disasters happen to punish us. They simply exist. And so to suggest, even in a metaphorical way, that place can be a character, is to miss the point; the existential bleakness of relationships between people and places. Our love for them is completely one-sided. I find our human connection to and love for places so mysterious and kind of tragic. I think an example of this is how reluctant people are sometimes to leave a place during a natural disaster. I think of the few people who died during the eruption of Mt. St. Helens because they wouldn't evacuate. This happens in almost all natural disasters - some people just won't leave. Why? And another question, why do people keep re-building in places where disaster is bound to strike again, flood plains, earthquake fault lines, etc.? We love places and feel like we know them, understand them, BELONG there, and then, whoops! tidal wave, earthquake, volcanic eruption, forest fire, flood. Dead people.

O'Shea: I love the pages in the story where you allowed the art to speak for itself and avoided any kind of dialogue or internal monologue--how important was it to you to have a good chunk of pages without dialogue--and how challenging was that to pull off for you?

Kelso: I've always been drawn to silent passages in comics. One of the masters of silent comics is Brian Ralph. And Mat Brinkman. Those guys had a huge influence on my work when I was doing Artichoke Tales. I have a fair amount to say as a cartoonist, and could never pull off an entirely silent comic that was any longer than 4 or so pages, because eventually, I want to SAY some shit, but I think silent passages in comics can be enormously effective, in allowing the reader to have their own thoughts and interpretation of events, and to serve as contrasts to especially talky passages. I love doing silent passages in comics because its a different kind of problem solving, figuring out how to convey things visually, how to employ atmospherics and rhythm to communicate. Also, it can be kind of a relief not to have to figure out where to put word balloons, and to just let the art open up into the whole panel.

O'Shea: Back in 2007, you created Watergate Sue for the New York Times. When doing different projects that took your mind away from Artichoke Tales, did taking that creative shift allow you to step away to a certain extent and get a fresh look at aspects of Artichoke that may have been challenging you?

Kelso: Over the years of working on Artichoke Tales, I set it aside numerous times to work on freelance jobs. Usually the breaks were about 6 months long, and every time I'd come back to Artichoke Tales, I'd sit down and read through all of what I'd done already and think hard about if I still liked the story, still liked where it was going. Those breaks usually did help in terms of getting perspective on the book, and finding ways to solve problems with it that had been bothering me. But I'm afraid the last break I took from it wound up being too long. What with having a baby, doing Watergate Sue, and moving, there was a two and a half year gap between finishing the pencilling and doing the final inking and production work. When I finally got back to work on it, I really struggled to re-engage. It wasn't that I didn't still like the story, it just felt separate from me. Old concerns. It wasn't til I got into re-drawing some panels, fixing some continuity stuff, that I finally re-connected with the book and felt my old love for it come back.