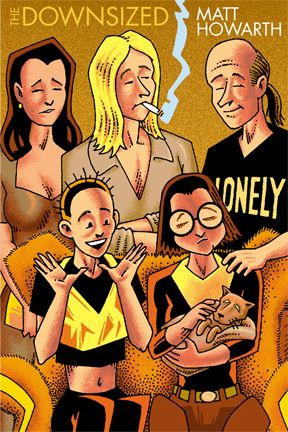

Years ago, my first taste of independent comics came via Matt Howarth's Those Annoying Post Bros. And since then, I've always found myself attracted to Howarth's visual style. So when my pal, AdHouse big chief Chris Pitzer, offered me a chance to email interview Howarth, regarding his new book The Downsized (set to be released in March) I was borderline giddy. This is an interview where I went in thinking I had done an adequate amount of research about Howarth's career, but I was pleasantly surprised to learn there was a hell of a lot I did not know about. After reading the interview, be sure to check out the seven-page preview of the 80-page book (described as "A parent's 50th wedding anniversary gives old friends a reason to reunite and take stock of their lives."). My thanks to Howarth for tolerating some of my ignorance to make for a solid examination of his creative interests.

Tim O'Shea: My first question is not uniquely about The Downsized, per se--but rather your work as a whole. How did you come upon the way you draw people's hairstyles? No one else (with the possible exception of Art Adams) draw hair in quite the unique way that you do (and I mean that as a compliment).

Matt Howarth: Years ago a friend remarked how weird my characters' hair was, forcing me to analyze why. I'm afraid the reason is more a limitation on my part than any stylistic choice. I've never been very adept with a brush; technical pens are my preferred instrument because they afford me more control over the lines. So instead of inking hair with supple brush strokes, I resort to dotted lines. As far as the overall shape of my characters' hairdos, I don't perceive hair as a collection of strands but as a mass, not unlike a piece of cloth draped atop someone's head. All rationalization aside, I'm afraid I draw hair the way I do because that's just the way it comes out.

O'Shea: I was really struck how the first panel of The Downsized took a point of view that features dialogue, yet with no characters shown. What promoted you to go with that shot--and did you hesitate to try it that way?

Howarth: That's purely a cinematic thing. Set the scene first, then have the characters enter from the wings. It was a way to deal with someone answering a door. I fret over details more than over settings, the latter comes instinctively, leaving me to agonize over the little things...like the open suitcase sitting there--implying that we're in a hotel room.

O'Shea: As you note yourself, this book is a departure from your typical work, in that it is a modern day, slice of life story. Has this been a story you've had developing in your mind over a number of years? Any interest in doing more slice of life tales, or are you satisfied with that genre after this one spin?

Howarth: Technically, this is my second slice of life tale; the first was "Magnesium Arc," a oneshot comic back in the 90s that told the story of fledgling electronic musicians as they progressed from practicing in their basement to their ultimate career goals. There was one chapter that deviated from reality in that it depicted an episode of a sci-fi cartoon series for which the band did the soundtrack, but the rest of the story was totally conventional. The same holds true for "The Downsized," with the exception of a subtle twist at the end, the entire story occurs in the real world.

My mind is prone to pursue strangeness when it comes to storylines, and in the real world there are strict guidelines (i.e.: laws of physics or social conventions) that act as limiting parameters. In storytelling, the writer is supposed to focus on an aspect of humanity as the crux of the tale...but my personal inclination is to get lost in the weird trappings that surround the characters, whether it be an alien world or a completely unrealistic scenario. I struggle to guide humanity back into the story, but often find myself constrained by the indigenous situations. Political or theological ramifications of our time have little bearing on a character's motivations if they live on a gas giant planet halfway across the galaxy a few hundred years in the future.

"The Downsized" gave me the opportunity to explore a story where the characters were the central issue. While it's a tale of people surviving off-the-books, the real focus is each character's perspective--not how they survive, but how that survival has changed them.

Initially I was inspired by the 50th wedding anniversary gathering of the parents of a friend of mine. I was fascinated by the idea of a bunch of family members reunited for such an event and how it enabled them to catch up on each other's lives, how people from a central unit could evolve in different directions, emotionally and careerwise, and how the economic crunch could crush those aspirations. Actually, there's very little autobiographical about the story. All of the characters in the book are concoctions of my own mind created to illustrate various points. Any aspects that might have been derived from real life were scrambled and mutated to fit the story's purposes.

While my forte remains tales of the weird, I am not adverse to doing more slice of life works. In the old days, I tended to do whatever stories occurred to me; these days I find myself tailoring the work to fit the needs of potential publishers. If somebody approaches me to do more slice-of-life stuff, I'll do it.

O'Shea: A cat plays prominently in the story. How early in the development of the plot did you arrive on the use of the cat as one of the story's focuses?

Howarth: The wedding anniversary gathering was my first building block in constructing the story, but the sick cat was a close second tangent. This part does come from my own life. Back in the 90s, my wife's cat had a stroke. Since Stasy had a 9-to-5 job, the task of caretaking the sick cat fell to me. I arranged a special spot in my studio where I could keep an eye on the cat while I worked. We didn't do much socializing during this period, since we needed to be around to watch the cat and tend to her needs. Going to our friend's parents' anniversary gathering was one time we "dared" to leave the cat alone for a period longer than an hour. We set the cat up on some baby-pads on the bed and hoped for the best. When we returned home, we found the cat in the living room. Although paralyzed by the stroke, the cat had managed to climb off the bed, down a hallway, down a flight of steps (ouch!) and over to the middle of the living room. She not only survived this journey, she began to regain her capabilities. I was really impressed by the cat's resolve to overcome adverse conditions and resume her normal existence. The synchronicity of this linked the anniversary gathering and the sick cat in my mind, so they became the central lynchpins of "The Downsized."

A lot of times this is how I build stories: starting with a concept or aspect and concocting the story to accommodate the parts I feel like dealing with. It's not a very professional way of going about crafting a story, but luckily my mind seems to go with the flow, devising connections and progressions as I move along.

O'Shea: In my mind, one of your greatest abilities is to create characters that stand out in a story and stick in readers' minds long after the story is read. For The Downsized, one of those characters is Uncle Marty. I have to know, do you have someone like Uncle Marty in your family or in your life?

Howarth: Nope, sorry. Being a lifelong smoker, I've come into contact with a lot of people like Uncle Marty--those who disapprove of other people's habits and those who feel compelled to force their own choices on others. I'm very intolerant of well-intentioned advice, especially when it's just a reason for people to try to force their own beliefs on me. I'm very comfortable with my vices and if the time comes for me to shed them, it'll be my choice.

O'Shea: Most of your work has been self-published, and yet in the case of the Downsized, it's published by AdHouse, how did it land there?

Howarth: It's a misnomer to think that the majority of my work is self-published. During the 70s, I started in self-publishing, but I swiftly spread out to working for a variety of publishers. This diversity has continued throughout my career, doing work for Fantagraphics, Dark Horse, Heavy Metal, DC Comics, TMNT, Aeon, Rip Off Press...ah, the list goes on and on, including a six year stint doing comics for a local newspaper during the late 80s. I even find time to squeeze in some commercial jobs. Yet all along I continued to self-publish things--mainly because my output is far more than any group of publishers could possibly handle. Since 2000, I've adapted my work to computer technology, which allows me to self-publish in digital form and avoid printing and warehousing costs. But during the last decade, I've still done numerous series and oneshots for a variety of publishers. I'm like a water faucet that's stuck and can't be turned off; things just keep on gushing out.

As to how "The Downsized" ended up with AdHouse...like so many things in my life, circumstances just come out of the blue and fall into place. Chris Pitzer had ordered some of my mail order stuff, and I noticed the company name on the envelope. I Googled AdHouse and then inquired if he might be interested in publishing something by me. Despite the plethora of material I produce that sees publication, there remains a wealth of unpublished work waiting to find a home. Interested publishers are welcome to inquire about this stuff.

O'Shea: A majority of your stories are black and white comics, is that a fiscal necessity or do you prefer working in b&w with most of your stories?

Howarth: For the first thirty years of my career I concentrated on the B&W medium for a variety of reasons, the strongest being that most independent publishers weren't interested in wrangling with color expenditures. I'm completely self-taught, so I never really had an art teacher to urge me to expand my techniques. I dabbled in color, mostly with magic markers for covers, but frankly I was never pleased with what I did. My work tends to be very precise, and markers are just too bleeding hard to control. The introduction of digital technology to my studio changed all that; it afforded me the ability to work in color in a means I could more effectively control. Since then, a lot of my self-published material has been full color (among them four Keif Llama graphic novels). Color has drastically altered the way I ink things, too, for all that dotwork and those thousands of tiny lines can get buried by color, so I've stopped wasting my time and now I rely on color effects to compensate for those missing elements. Which doesn't mean that I've stopped doing all the detailed inking for B&W work--it all depends on how the thing's going to be reproduced. An example would be the "Stalking Arr" strip which was done in B&W, but Heavy Metal wanted the art colored--so I colored it. Doing so was somewhat problematic since the inking was quite dense in parts and all that detailing got buried by the colors. Fortunately my color sense is somewhat garish, so the bright colors didn't entirely swamp the details.

O'Shea: I would be remiss if I did not ask, do you listen to music as you work? If so, what was in heavy rotation while you worked on The Downsized? On the other hand, is there any music that you would recommend folks listen to while reading the story?

Howarth: Music has always been an integral part of my work process. And it often creeps out of the inspiration department and right into the stories, like with all the musicians who appeared in my Savage Henry series. It's pretty obvious that I'm obsessed with fusing music and comics.

Alas, I did "The Downsized" back in the mid-90s...so I'm afraid I can't recall whatever was used as my sonic fuel. My tastes in music tend to be somewhat eccentric. Let's see...mid-90s, I was pretty immersed in the techno scene, so it might have been: Orbital, the Future Sound of London, Spicelab, a lot of stuff on the (now defunct) Harthouse label. But my choices tend to switch according to mood or whatever I've just gotten, so who can say for sure. Some of my mainstays are: Tangerine Dream, Hawkwind, the Cure, Heldon, Bill Nelson, Frank Zappa, Wire, Magma, Gong, Miles Davis, Frontline Assembly, King Crimson, Can, Cocteau Twins, Front 242. As an audiophile can tell, my tastes are all over the place and not really centrally confined to any one genre.

As to a recommended soundtrack to read the story...I would suggest something nostalgic to the reader, for that might capture some of the tale's reminiscent nature.

O'Shea: Without giving aspects of the story away, there is an element of the narrative that goes on another plane of existence to a certain extent toward the end. I was struck at how you conveyed that with a shift in tones for the pages. Was that a look you arrived upon after trying it other ways, or was that always the way you had planned?

Howarth: What you see is how I saw it. By dealing in tones, certain aspects are immediately separated from the reality of the tale--an easy visual cue for the reader. There are a variety of ways to achieve this forced difference. In the Doctor Thirteen oneshot I did for Vertigo, I used different panel borders to mark different types of scenes. This time, gray tones seemed to better fit what I wanted to convey.

O'Shea: I know you had a new strip ("Stalking Arr") in the January 2011 issue of Heavy Metal, but what else do you creatively have coming up in 2011?

Howarth: As I mentioned before, I'm obsessed with combining comics and music, so let's return to that fixation as a lead-in to answering that question...

Most artists with strong musical interests would have been happy doing album covers, and I've done my share of them--but for a looong time I've wanted to take it further and do stories that would come as part of an album and the music would be a soundtrack for the story. All through the 80s and 90s, I continually pitched these type of projects to labels and publishers, only to be shot down. Publishers would tell me, "This is an album, you need to talk to a record label," while labels would say "This is a comic book, you should be talking to a book publisher, not us." The advent of digital technology abolished those restrictive parameters. Suddenly the comic could be put on the CD as a digital file, avoiding any printing costs. Consequently labels were more receptive to the idea.

A percentage of my work during the last decade has pursued this life-long ambition, and as a result this stuff has gone unnoticed by the comics field. I've done several of these collaborations (with Klaus Schulze, Hugh Hopper, Quarkspace, Radio Massacre International, Conrad Schnitzler, Galactic Anthems, Mental Anguish, Michael Chocholak, Syndromeda, Heuristics Inc, Bill Nelson, Arthur Brown, and more bands).

The Bill Nelson project is due to be released soon--that's definitely the most ambitious of them. "The Last of the Neon Cynics" will include an entire graphic novel, over 100 pages and in color. The process involved a lot of back and forth between me and Bill, coming up with a story we both liked and incorporating Bill's suggestions into the work. There's a scene in which the hero serenades the girl over an electric campfire--that part was left undone in the initial run-through. So Bill wrote a song for the hero to sing featuring some psychedelic guitar alongside some twangy cowboy riffs. Then I added a scene in which the hero plugs in a computer program to teach him to play guitar. This program offers the hero different guitar styles he could use, and avatars of Jimi Hendrix and Chet Atkins try to convince the hero to pick them because their music will give him more of a romantic edge. (Laughs.) "May you never hear surf music again."

Another example of collaborative interaction happened with the Radio Massacre International project. I came up with the story which was then approved by the band. While I was working on the comic, RMI came over from England and played a radio concert on Star's End on WXPN in Philly. I got to sit in my studio, working on the comic while listening to the concert on the radio. When the comic was done, the band did songs directly inspired by the story. When it came time to hand off the album to a label, the band wanted to include part of that radio gig as a second disc--did I have a problem with that? Ha--of course not. They had no idea that the gig had already been integral in the story's creation. Adding the concert to the project was just collecting all the diverse influences together.

Effectively these music collab projects are simply a revival of concept albums from the 70s, this time providing visual stories to back up the thematic music. One must keep in mind that most of these collab projects have involved instrumental music, so the connections between the story and the music rely heavily on the emotional content of the songs. And the song titles.

Other up-coming music collabs include albums with Ozone Player (a musician from Finland) and another with UK synthesist David Wright (for this one I wrote a text story instead of a comic strip).

I've also been doing a lot of writing and have produced over fifteen prose novels since 2000, most of which were self-published in digital form and are available as digital downloads or print-on-demand volumes via my online catalog (www.bugtownmall.com). Currently I have a few novels being considered by a variety of book publishers. And there's a stack of other novels waiting to find homes.

My production rate is remarkably fast. I could get killed tomorrow by a meteorite and there'd be enough finished previously unpublished stuff to keep fans entertained for another decade.