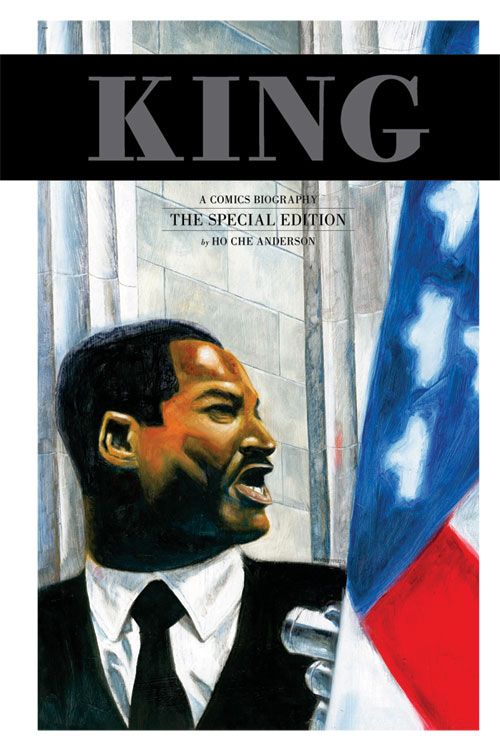

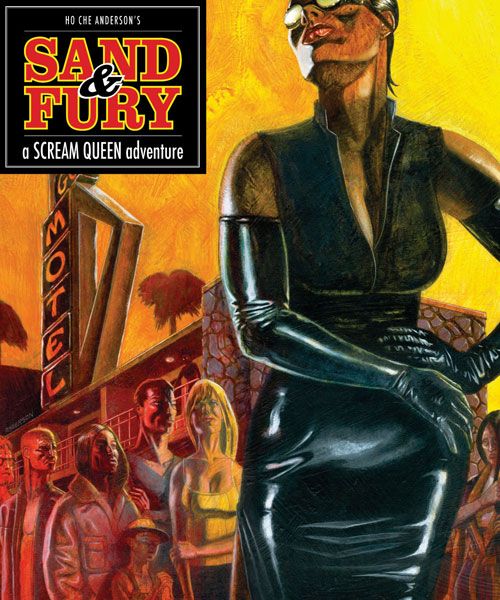

My Robot 6 associate Tom Bondurant praised Ho Che Anderson's Sand & Fury yesterday. It's just one of the two books that is coming from Fantagraphics and Anderson this year. The other book is the collected edition of Anderson's (originally released from 1993-2002 in three volumes) biography of Martin Luther King Jr, King. We got a chance recently to discuss both works, via email. And I also was fortunate enough to find out what his creative plans are for the future--and to my surprise, it does not involve graphic novels. Anderson's two works gave me the opportunity to go in a lot of different directions in this interview, and fortunately he was willing to play along in the discussion. My thanks for his time.

Tim O'Shea: How much did you research MLK before embarking on such an ambitious project back in 1991?

Ho Che Anderson: I sat in my parent’s basement for something like six months and read a bunch of books and watched a bunch of videos. I read King bios, stuff about the general time period, stuff about the civil rights movement and it’s more militant ancillaries, and I watched much documentary footage. I had a lot of fun doing my research, I wish I could have gone more in-depth but eventually I had to pull myself out of it and just get to work writing and drawing the comic.

O'Shea: While compiling the previously released issues into this collected edition I know that you deleted some scenes (included in the book, as a variation on DVD extras). Am I correct in thinking you re-lettered the whole story? Were there other major changes you were able to make?

Anderson: Yeah, me and Paul Baresh re-lettered the entire thing. No one was ever satisfied with the cheesy computer font I choose for other editions of the book, myself chief among them and when they proposed this latest and probably last edition the first thing I knew we were going to do was redo that font. Other alterations were changing the shape of the balloons in the last chapter from rectangles to the ellipses used in the first two chapters and re-writing some of the dialog. That’s one thing I wish I could have done more of, slashing dialog, rewriting more of it, but at a certain point you gotta let it go. (Yes, George Lucas, I am talking about you.) The other changes from the original mini-series were made in the first collected edition a few years ago, where I dropped some old scenes and added some new ones. The deletion of the entire childhood sequence that originally appeared in 1993 was one major change from mini-series to collection, and the story is the better for its not being there as far as I’m concerned. We definitely had DVDs in mind when we added all those extras at the end. I wanted to do the Lord of the Rings of comics in terms of behind-the-scenes extras.

O'Shea: The first third of the tale is told predominantly in black and white (with some stellar exceptions, such as the transition of MLK's lit match for his cigarette to a firebombing of MLK's house), but as the story goes on it shifts into predominantly full color, can you explain what your thinking was in doing this?

Anderson: As is often my answer, it just evolved naturally. When I started the comic it was always a black and white book and that was fine. Eight, nine years later and I’m working on the final volume, and I was just feeling like doing it in color. In fact doing the book in color and using the computer to composite and finish the pages is what got me excited about completing the book in the first place so I just decided to go with my gut even though it violently contradicted what had come before. In some ways I think it almost works in that as King’s life becomes more strife-filled we introduce more and more color but if indeed it does sort of play that way it was an afterthought and not part of the book’s original DNA. What’s ironic is that if I were to be tackling the third and final volume today it would look a hell of a lot more like the first two volumes. My drawing style seems to have cycled back to where I began—just as I’m finally ready to step away from this crazy medium.

O'Shea: How early in the development of this biography did you realize you wanted to make the music of the period a major prop/element of the tale?

Anderson: From day one I would suspect. The thing is, I’m a frustrated filmmaker, and I’ve always envied the vast array of tools available to filmmakers, one of which of course is music. Having music inform a period tale is a natural, to set the mood, to orient the reader to the time period, and even though I couldn’t use the actual music, I could at least use song lyrics to suggest music. A lot of the stuff that made it into the book was stuff I was listening to a lot while working on the book to set the mood for myself so it pretty naturally worked its way onto the finished pages. Also, I was highly influenced by the work of Howard Chaykin at this point who used a lot of typography as a graphic element in his work and I’m sure that played some part in the decision to go that route. I think part of me was hoping the reader might identify some of the songs and play them as they read the book, but I’m sure that’s never actually happened.

O'Shea: You give folks an amazing glimpse of the creative process in this new collection, this particular snippet really caught my attention: "After eight years I finally finish drawing King 2. I always think there will be some catharsis when I finish a project but there never is. The day I finished King 1 was just another day, distinguished only by its sameness. I expect there to be a glow around me, the feeling of a weight being lifted. There isn’t." Do you think the weight will ever feel lifted—and if it is, are you afraid your creative drive will disappear with it?

Anderson: Not at all. The creative drive is innate, not to be dampened merely by any relief I may experience in completing a project. I sometimes wish it would go away to be honest, my desire to be a storyteller has brought me much more pain than it has ever brought me pleasure. This whole endeavor has and continues to feel like a weight, only it’s the weight of failure. Sadly, my career as a cartoonist has always been something of a non-starter.

O'Shea: Was there any pushback editorially to including Black Dogs in the collection, or was it always known that had to be part of the collected edition?

Anderson: If there was any pushback it was from me, because that story is impossible for me to read at this point. It’s so naïve and shrill, I just can’t take it. It was my idea to include it, it just seemed like a natural, and I suggested it to Gary Groth and he thought it was a good idea and we left it alone. Then a few weeks later I actually picked the thing up again for the first time in like, ten years, and it was even worse than I remembered it. I suggested we should maybe not include it at that point but GG still thought it was a good idea, and well, it made it into the book so I guess he won out. I’m not entirely sorry it’s there, but it’s still a painful thing to look at. I just was not good at my craft in those days.

O'Shea: I'm fascinated by your lettering style in both King and Sand & Fury--how did you end up with such a unique style?

Anderson: I think I’ve retired that lettering style but it seemed to work for those two stories. As I worked on King, especially the last chapter, my style seemed to be getting more and more blocky, for lack of a better word, more chunky and expressionistic, and I wanted to create a lettering style that complimented that look. I designed a title font in that style (used on the original King Vol.3 cover) and liked the look of it, and it evolved into a balloon lettering style as well. It has a baroque quality I like, kind of jagged and tough, like some of my stories. I used a computer font based on my letters for King whereas Sand & Fury was actual hand lettering on boards, which I can guarantee is the last time I’m ever going to do that.

O'Shea: With Sand & Fury--what made you want to tackle a story that is a mixture of horror and eroticism?

Anderson: To me, sex and horror or sex and violence seem to go naturally together. They seem to stem from the same twisted areas of our psyches. What scares us can often arouse us, sometimes despite ourselves, and vice versa. Sex I think can be horrifying for many reasons; being naked in front of someone and thus vulnerable physically and emotionally is scary, the idea of entering another person’s body or even more extremely, having someone enter your body, this is not an activity without significant potential for trauma. I’m not a total horror junkie the way I am about sci-fi for example, but I’ve always loved horror stories, specifically horror movies—I didn’t know that I was doing one when I started this (this story was actually largely made up as I wrote it which is a first for me, I usually plan out my stuff before writing), but when I realized I was writing a horror story I got very excited. I wanted to write a dark tale about a woman with profound secrets, and for me as a writer when I consider a character like that it always seems to go in the direction of a person with a dark sexual life; I guess I’m just a pervert by nature. That kind of thing can be off-putting for many if not most but I’ve always found people’s crazed sex lives fascinating. There are just areas of the human experience that you can explore in this kind of tale more than you can in your average story. But after this symphony of darkness the next thing I do is going to be of a considerably lighter nature.

O'Shea: In terms of your use of submissive relationships, it seems to revisit an aspect that you explored in I Want to Be Your Dog. What is it about submissive relationships that draws you to utilizing them in your fiction?

Anderson: That’s interesting, I hadn’t noticed that before. And it’s true, the submissive/dominant dynamic is something I find intriguing. I’m shocked you’ve read Dog, by the way, and I apologize for inflicting it on you, sir. It’s interesting because the main character in Sand & Fury is a very strong person in her intimate relationships, I’d go so far as to say she’s the dominant in most cases, despite her petite appearance, yet she also has a side of her as I detail in one particular scene, that wants to submit to others completely. It’s often the case that people who are powerful in one realm, work for example, have the desire to submit in their private sphere. I think I return to the theme from time to time because the human will is a compelling thing. The idea of taking someone who is strong-willed and yet having them break against the will of another and suddenly find themselves doing things they would under other circumstances find appalling, and what’s more finding themselves enjoying that appalling behavior is gripping stuff for me. I think all writers have at most three or four themes they return to again and again, and I guess for good or ill that’s one of mine.

O'Shea: As noted on the back cover, you were inspired "by the work of David Lynch, Dario Argento, and Richard Sala. Can you share which films of Lynch and Argento, as well as stories by Sala that in particular inspire this story?

Anderson: There was a laundry list of people I suggested to Gary, who wrote the back cover blurb, that inspired me on that book and he chose three of the best. With Lynch I’ve enjoyed every movie of his that I’ve seen and I’ve seen them all except The Straight Story which is on my list. But it was Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, and even a bit of Inland Empire that I drew on for inspiration this time, particularly Velvet and Inland, Velvet because of its toughness and its dark eroticism, and Inland because of its dream logic. If you examine my story based on real world logic it falls apart pretty quickly, but it’s not supposed to operate under that framework, it’s more a waking dream than a logical narrative. I’ve only seen two of Dario Argento’s films and they both inspired this, Suspiria and Tenebre. I took similar things from Argento as from Lynch, a kind of surreal narrative progression, as well as his love of blood and extreme violence, and also how gender factors into the work, which is an old trope of mine. I’m fascinated by our fears of each other, women’s fear of men but more specifically men’s fear of women, and how our physical strength lends more destructive overtones to how our fear manifests. From Richard Sala I took the joy of telling a baroque horror story in comics. My favorite Sala work (so far) is The Chuckling Whatsit, which I recently reread, and I thought about that one often while working on this book. I loved its twisty, complex storyline and, again Sala’s use of violence. In another one of his stories he’s got a character going around with masks with spikes on their inside and using a mallet to bash the masks onto and into people’s faces. That is wonderful over-the-top theatrical violence and I wanted to get a bit of that flavor in my stuff.

O'Shea: Anything we should broach that I neglected to ask you about?

Anderson: I’ve got one more publication I’m putting out next year, an omnibus book collecting a bunch of comics and illustrations done for various publications over the last ten to twelve years. And after that I’m putting the whole sorry spectacle that was my comic book “career” to a much-needed end. It was fun—at times—but it never really worked out. After years of being frustrated filmmaker, I’m finally getting off my skinny heinie and trying to make that dream a reality. I’m currently cutting my first short film, the crime drama The Salesman, and have applied to a great film school here in Toronto, which, if I get in, will be a great place to launch a legitimate film career. So please wish me luck—I am gonna need it.