At the risk of sounding like a library poster encouraging youth literacy, reading can take you on a journey ... whether you're reading a comic book or one of those lame old books with no pictures.

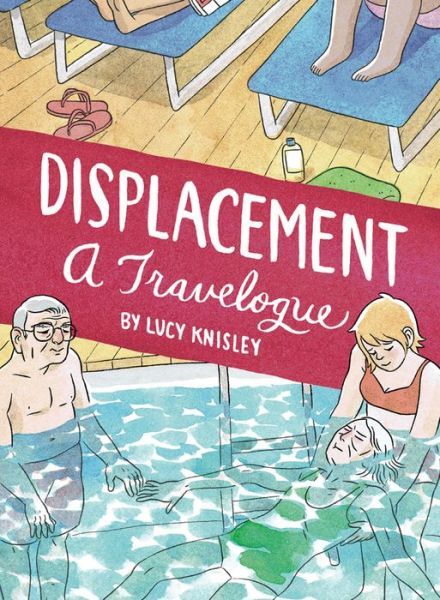

Sometimes those journeys can be quite literal, as in the case of Lucy Knisley's travelogue Displacement, chronicling the cartoonist's 10-day Caribbean cruise with her grandparents.

"Caribbean cruise" probably sounds pretty nice, especially to those of us hiding from the snow and cold, but this is not the sort of live-it-up-while-you're-young trip chronicled in Knisley's previous book, Age of License. Knisley's grands, as she calls them, are in their 90s, and her grandmother suffers from dementia, to the point where she often wouldn't recognize her own granddaughter.

So maybe they shouldn't be going on a cruise at all, one might think. But what if they had a 27-year-old loved one to take care of them during the trip? That should work fine, right?

"And hey," Knisley's cartoon avatar thinks when weighing the decision of whether to go along, "Might make for a good story."

And that it does. If you were a little envious while living vicariously through Knisley in Age of License, then you should feel the opposite here: She takes a cruise on a giant ship full of the elderly; her grands require almost constant attention and care; the entertainment isn't exactly entertaining; and her room is a windowless cell of complete darkness. The one time she does get to temporarily sneak away for something fun — a snorkeling excursion — upon her return she's unable to find her grandparents, and the cruise organizer whose care she left them in seems maddeningly blase about it.

During the trip, Knisley reads her grandfather's memoir of his time in World War II, at which point the comics format gives way to more illustrated prose, with Knisley filling the pages with transcriptions of anecdotes. Together with her own memories of the pair, these help transform the book into a chronicle of the humorous-in-retrospect hardships she faced into a sort of meditation on aging, of life as a whole thing incorporating past as well as present and Knisley's family story.

Knisley's delicate linework looks more delicate still in the small format of the book—it's 7.5 by 5.5—and it's fully water-colored, making it an at times almost brilliantly bright and colorful work (Knisley often also colors dialogue balloons and captions, too) while still-looking hand-made.

It also allows her to do an awful lot of dramatic storytelling just in the coloring of her characters' faces, as their cheeks flush with occasional bursts of emotion.

Despite the many travails she faced on her travels, it ends up being a pretty positive experience for all involved ... including, of course, the reader.

For a journey into even stranger territory — perhaps the strangest, most alien territory you can visit through comic books at the moment — you might want to try Luke Ramsey's Intelligent Sentient?.

If indeed Intelligent Sentient? is a comic book or graphic novel; it reads more like a picture book in which the publishers left out the text and mixed up some of the pages. There are no words in it at all, and no panels — other than those implied by the borders of the pages, as every page is its own discrete image (until a reader reaches the end of the book, where each spread becomes its own discrete image).

Whether one wants to call Ramsey's book comics, it's definitely sequential art, in that it's bound art in sequence, and it's telling a story, even if it's somewhat abstract, and leaves plenty of room for interpretation.

It definitely involves snakes, however. Ramsey's pages are full of snakes, of a very particular cartoon species, wherein they are basically just smooth, featureless squiggles with blank, black dot eyes. They appear on almost every page, sometimes right where you might expect a snake to be, but more often than not in unexpected places, like forming the mass of a trio of large snake-men, one of whom is dressed like an ancient South American god and another as an old-school biker stereotype, or forming a sort of hand, their long tongues manipulating a man like a marionette, and so on.

The wordless nature, and the incredible amount of detail in almost every page — details that change in style, from pieces that evoke old underground comics to others that evoke Hieronymus Bosch -- along with the impression that everything is made of snakes, may remind certain readers of a trip in the hallucinogenic drug-taking sense as much as the travel sense.

The single images are generally quite astounding, each given so much attention and detail they look like they were individually produced for a gallery wall, like, for example, the first image, an explosion of prehistoric sea life, over 100 animals, filling every available space on the page, overlapping in a blast of rainbow colors, and all streaming toward a handful of those aforementioned snakes (see the top of the post).

Prehistoric life appears in several pages/images, as does what appear to be some sort of alien or other culture that captures and performs experiments on people, and, near the end, a large, ghostly person — or race of people, if they are different individuals — who travels through insanely detailed landscapes and locales of varying styles.

It's an unsettling book in that it seems quite clear from the repeating motifs, and the beginning and ending, that there is a story being told, and while almost all of the symbols and signifiers are ones that are recognizable, their usage is cryptic. The result is a story that reads like a secret, a secret that can't be unraveled without some sort of missing key or Rosetta Stone.

Like a beautiful stranger seen in the street, I can't tell you what it's all about, but I do like looking at and admiring the craftsmanship that must have went into it (and unlike a human being, it's not rude to stare Intelligent Sentient?).