In "Starve" #2 by Brian Wood and Danijel Zezelj, Gavin Cruikshank -- a washed-up chef with a mouth and a strut like a debauched rock star -- continues to be the main attraction. In the first issue, Wood all but admitted that the character is based on Anthony Bourdain by describing how Starve used to be "a hip little show where I roamed the planet," just like Bourdain's "No Reservations." Now, the show's degenerated in the love child of "Iron Chef," "Fear Factor" and "Real Housewives." Now, it's more about competition, status and titillation than talent, sustenance or community.

Wood expands on Gavin's character through a personal reference and a declaration of war. Gavin visits the only other "honest, legit old school chef left in this city," Dina Stern. Zezelj's spectacular pacing and dramatic tableau complete with a pig's head make Dina's introduction unforgettable. Her frankness and toughness impress, and thus her willingness to do Gavin a major favor counts. On the battlefield of the show, what started Gavin's simple quest to get back on track with job and family twists into something more. By the end of the issue, whether he intended it or not, Gavin demands to be redeemed as a chef and a citizen. Like Gavin, "Starve" has got a revolutionary bent along with all the swearing and booze.

Wood makes his targets clear: reality TV and the 1%, who represent greed, denial and the twin pacifiers of spectacle and consumption. Like Rucka and Lark's "Lazarus," "Starve" takes a dark view of a world dominated by the 1%, but the two dystopias have different forefathers. Wood's nightmare of the lowest common denominator is closer to Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World" than to George Orwell's fear of fascism in "1984." As cultural critic Neil Postman wrote, "Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy and the centrifugal bumblepuppy."

"Starve" has been meat-centric so far in its food-as-commentary symbolism. Historically, meat's been the most costly foodstuff for our wallets and consciences. Gavin strategizes like a general, thinking over his opponents' predictable choices. In the end, his own choice is also predictable. I knew even before Gavin plated his dish that it would have to be sashimi. In the food world, applying heat to the best sushi-grade fish is a crime, perhaps even worse than the more common crime of asking steak to be cooked till well-done. Gavin would not dishonor Dina, himself or the fish by anything less than serving it raw. Dave Stewart's colors the sashimi a perfect pink, giving Gavin's dish an aura of lightness and purity, foreshadowing Gavin's victory.

Despite strong characterization, the stakes remain melodramatic -- Gavin could lose access to his kid if he doesn't win! -- and Wood is too eager to make his philosophical points. Through Gavin's textbox voiceovers, Wood tells the reader how to feel and what to think, connecting the dots instead of just evoking outrage and letting both audiences draw their own conclusions. The result is a couple shades too preachy and simple-minded, and this detracts from both story and message.

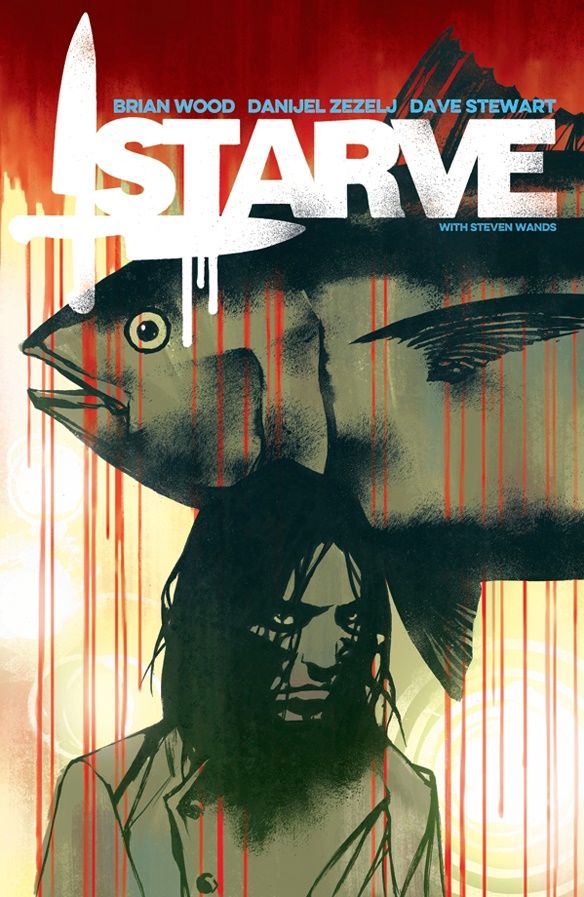

Zezelj's style is unusually strong and distinctive, and he builds pages around the angles of jaws, strands of hair, heavy outlines and charcoal-like shading. It won't be to everyone's taste, but his swirling, liberal use of black ink has intense emotional energy, leading the reader's eye around the page like a graceful but imperious dance partner. The results can be gorgeous, like the hazy shadows and fisheye composition in the issue's first interior. His transitions and facial expressions are fine, and he can make meat and blood look pretty without removing their horror.

Stewart's colors are a great partner to Zezelj's ink. Most of the "Starve" #2 is a little too dark, but that's probably intended to reinforce mood. His palette is rich and warm, with hues that look like dirty stained glass in Zezelj's frames. When Stewart uses more light, his work in "Starve" #2 becomes extraordinary. In particular, Roman's apartment and the city at night are beautifully dreamlike, looking almost blurred by their illumination. The graffiti and cats in the scene in which Gavin carries the bluefin are unforgettable. Zezelj and Stewart pair a light-over-dark sky with traditionally dark-on-light figures and foreground to make an ordinary exit look epic, as if Gavin was a hero out of myth, carrying a sacrifice home to his gods.

"Starve" #2 has good ingredients that are overseasoned with didacticism, but if Zezelj and Stewart's art is to the reader's taste, they'll still be hungry for more.