Here's what we talk about when we talk about comics.

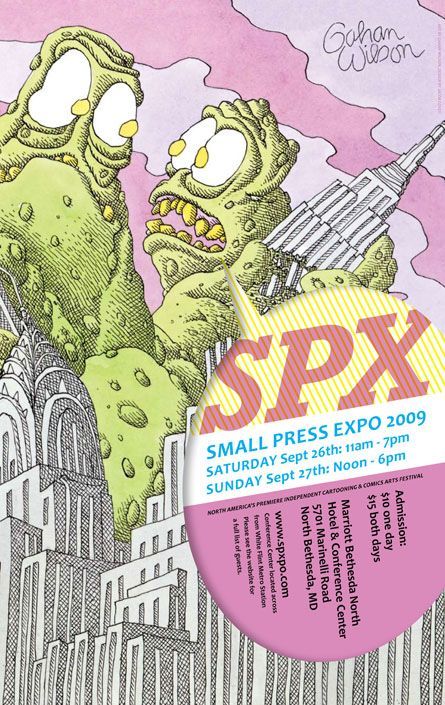

In front of a packed house at September's Small Press Expo in Bethesda, Maryland, a group of critics from around the comics Internet and beyond talked shop at the annual Critics Roundtable panel. Moderated by Bill Kartalopolous, the panel featured Comics Journal founder Gary Groth, New York Times critic Douglas Wolk, bloggers Joe "Jog" McCulloch, Tucker Stone, and Rob Clough, and a pair of Robot 6ers, Chris Mautner and myself. I'm happy to present a transcript of the panel below.

Sure, I'm a little biased, but I think it's a fascinating discussion. The topics include the differences between print and online criticism, the notion of "the critical discourse," negative critiques and much more. For some panelists, things have already changed since the panel took place: Groth, who gets quizzed on why he isn't a bigger contributor to the comics Internet, is getting ready to jump in with both feet with the relaunched Comics Journal, of which Clough is going to be a part; while my membership in Robot 6 wasn't even a glimmer in JK Parkin's eye yet. And with a good deal of familiarity between the critics -- I believe seven out of eight have written for the Journal and half write for The Savage Critic(s) -- the back-and-forth was fluid.

If you'd like to listen along, you can download this mp3 recording of the panel. It's worth it just to hear the chaos surrounding Tucker's bathroom break.

Click the jump to read the transcript. Now, without further ado...

Bill Kartalopolous: Look at this crowd! And I mean the panelists. [Laughter] Ba-dum-bum-bum. Okay. Hi, my name is Bill Kartalopolous. I'm the programming coordinator here at SPX. I also teach classes about comics and illustration at Parsons, and write about comics for Publishers Review and Print magazine. Publishers Weekly is actually what it's called, isn't it? It could be called Publishers Review. I just look at the number on the check. Then I cry. [Laughter]

Rob Clough: Is it a handwritten check?

Bill: Yeah, right. I don't think the signature's even handwritten. Okay, so, this is our annual Critics Roundtable. I'm very, very excited that there's so many notable critics here at the show this weekend that I just had to invite everyone on to the panel. I'm really briefly going to introduce everyone and mention one or two of the publications they write for. Some of them write for many, many publications, but it would take probably the remainder of the panel to communicate all of our CVs collectively. But going in, I think, alphabetical order, as I have them here: Rob Clough [prounounced "claw"]...

Rob: "Clow." [rhymes with cow or Mao]

Bill: "Clow." Sorry, I always do that.

Rob: And I always correct it.

Bill: Frequent comics reviewer for the seems-to-be indefinitely on hiatus Sequart website --

Rob: Coming back soon!

Bill: Coming back soon to a computer monitor near you. But now reviewing on your own High-Low blog, and writing many many reviews, as many as three a week it seems, very very frequent reviewer. We have Sean Collins, Sean T. Collins -- I always do that too... [Laughter] ... who maintains his own blog called Attentiondeficitdisorderly All Too Flat... ?

Sean T. Collins: Close enough.

Bill: What did I get wrong?

Sean: The "All" isn't in there. The "All" is silent. [Laughter]

Bill: Okay, Attentiondeficitdisorderly Too Flat. Right. But you also write for The Savage Critic group blog, and you've written for a number of publications, from Wizard to Maxim to many others I'm flaking on right now. A very frequent writer for all of those venues and more. Gary Groth all the way at the end, a person probably without whom many of us would not be in this room. The co-founder of The Comics Journal, co-founder and co-publisher of Fantagraphics Books, longstanding editorial director of The Comics Journal, the writer of many pieces of savage criticism that we've all admired over the years, setting a real standard for everyone else.

Gary Groth: Not all. [Laughter]

Bill: Not all. But someone who we're always happy to have on this panel. We have Chris Mautner [pronounced "Mawtner"]...

Chris Mautner: "Mowtner." [rhymes with cow-tner or Mao-tner]

Bill: "Mowtner." It's gonna be one of those panels. [Laughter] He's frequently reviewed comics for the Patriot News in Harrisburg?

Chris: In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. I had a column there.

Bill: And also a frequent writer for the Robot 6 blog at Comic Book Resources. And most of what you do for that is reviewing.

Chris: Reviewing, and we have some column features, regular features, and kinda daily blogging. And I also do reviews for The Comics Journal.

Bill: And immediately to your right, Joe McCulloch?

Joe McCulloch: Yes. Perfect.

Bill: Phew! AKA Jog?

Joe: Yes.

Bill: Author of the blog Jog Likes Comics?

Joe: Yes.

Bill: Okay. Also writing for Comics Comics magazine, The Savage Critic, Bookforum, among many other venues. Also recently started writing a comics column, a kind of comics and movies column, for the ComiXology website called... "The Watchman."

Joe: [Laughs] I inherited that, yes.

Bill: I should hope so! [Laughter] Immediately to my left, Tucker Stone maintains the Factual Opinion blog, featuring many comics reviews by yourself and also by your significant other. I think those are the only two contributors, or do you have any other...

Tucker: No, we have a couple other people, but for comics it's just my wife and I.

Bill: And you've also recently started doing a series of video reviews for the ComiXology website.

Tucker: I guess you could call it that.

Bill: In which you sort of performatively communicate opinions about comics and the comics industry and culture...

Tucker: Okay. [Laughter]

Bill: Okay, something like that?

Tucker: Yeah, that's accurate.

Bill: And right over there, Douglas Wolk, a man we all know and love who writes for many many publications, including Publishers Weekly, or if you prefer, Publishers Review. [Laughter] Very frequently recently writing for The New York Times, very long pieces of comics criticism. Also the author of the book Reading Comics

, and you've been in 8,000 other magazines, newspapers, websites, also The Savage Critic, et cetera.

So I think we've covered everyone, basically. And that's about time... [Laughter] There are a lot of issues we could start with, and there are two that leap to mind the most. I'm not actually sure which one's better, but they're both related. One of the things I'm interested in, because so many of the people here on this panel write most frequently on the Internet and often for their own fora, their own blogs, or at least websites that are written collectively by a small group of people. So I'm interested in the question of how the Internet has affected comics criticism in good ways and in bad ways. That's a very broad and general question. Since many of you are writing for the Internet, maybe the easiest place to start -- anyone can jump in on this -- is what you perceive as being one of the advantages of this new, pretty much dominant mass medium in our lives that's leeching the life out of everything else. Joe, do you have any thoughts on this?

Joe: Yeah, well, one of the plus sides of the Internet, definitely, is that you can respond quickly to something -- not necessarily a new book that's come out, but something that you're interested in and studying, so to speak. I tend to study things after I read them. So you can get things out there quickly, and then they're out there. You could find them on search engines. Whether they could be found, or whether they're permament, is another question, but the potential is there to access them easier than you can something that's, say, in a bookstore, or in a magazine longbox. I think that's a good plus. And of course this is a minus too, but you can write how you want, you can address works the way you feel like you want to, you can just change topics if you want to, you don't have to feel constrained to write about only new things, about only a certain genre, about only a certain format.

Douglas: It enables conversations, too, which is what's most rewarding for me -- not just seeing the article but seeing the responses to it and the comments and the things that people write in response to it and other responses to that. But the conversation happens much more quickly and much more broadly than it was able to in the past, and I love that.

Sean: I guess this is a little bit obvious, but there's no gatekeeper, there's no editor, there's no publisher to answer to. So, speaking for myself, and I think Joe, and probably Tucker, the Internet is where I first ever wrote about comics -- I think probably, maybe on the Savage Dragon message board, and then on the Comics Journal message board, and then on my blog. Then a few years ago, Dirk Deppey, when he was managing editor of The Comics Journal, brought a bunch of people who were primarily bloggers aboard. And that still happens. I never would have dreamed of submitting anything to The Comics Journal. It was just way beyond my ken, I thought. And then all of a sudden I'm writing for it, and that never would have happened if I hadn't started a blog on my friend's humor website and started writing about comics.

Chris: I do think there's some kind of promotional aspect to the Internet and writing on the Internet that allows you -- and it's part of that direct conversation -- that you can... I think if I'd just been writing for the newspaper, I don't think I would have met these people or have access. Unless I'd put it up on a blog, I wouldn't be doing the work I'm doing at Robot 6. So there is that self-gratifying notion of being able to, I don't want to say call attention to yourself, but at least the reward of people paying attention, which can lead to other things. It can lead to greater writing rewards down the line.

Rob: The thing about it for me is that there's potential there... When you're writing for a publication there's space constraints, there's editorial constraints, but there's a real possibility to write long, thoughtful, critical pieces, and really engage something. And unfortunately, on the Internet, that doesn't always happen. Too many online critical spaces are just shorter reviews or short excuses for snark as opposed to really trying to engage the work, both for its positive and negative qualities. To me, that's the greatest possibility there for the Internet, for those who are really willing to engage it, is that a lot can be done that can't sincerely be done in a publication.

Bill: I talked to some of the panelists ahead of time to see what kind of topics they were interested in or questions they might be interested in, and Sean directly wanted to know, Gary, why you don't have a blog or haven't participated in online fora or some kind of writing of that nature, beyond the fact that you're obviously a very busy publisher.

Gary: Yeah. Well, I don't know. People bug me about not having a blog all the time. First of all, I'm generationally challenged in terms of having a blog. I mean, I'm just not suited to writing every two days. I'm from the tradition where you sit down and you spend several weeks honing some piece. So I haven't been able to get into the rhythm of blogging. Plus, in terms of criticism, the criticism I write has been somewhat dilettantish because of my position as the publisher of The Comics Journal, and that's only gotten more acute over the years. So I don't feel like I can really whale on a lot of books, because it would look immediately like this is obviously a conflict of interest. So I feel somewhat compromised in terms of writing about specific books. Then I also don't necessarily want to write only about the books that I love, because there a lot of books that I read that I don't think much of that I'd love to write about, but I just feel like I'm in a difficult position to do that. I don't know if that sort of incoherent rambling answered your question.

Rob: You felt your position has changed? I mean, you've been the publisher for a long time.

Gary: I think it has, because the Journal has shrunk as a proportion of Fantagraphics over the years. As we publish more and more books, more graphic novels -- we publish something like sixty graphic novels a year. So in 1986 or 1988 we publish eight books a year, and The Comics Journal was a much more prominent part of our company, and I was much more involved in it, and now I'm much more involved in publishing the books. So I think it has changed somewhat.

Bill: And that thing you pointed out as well, I think, is sort of the other side of the coin from the networking aspect of blogging and writing online, which is that often, in order to be a presence, as Gary suggested, it's helpful to be generating content on something resembling a regular schedule, which maybe works against the kind of writing you were talking about -- spending two weeks trying to write your definitive statement on X, Y, or Z. Is that something any of you have felt? That there's some sort of pressure to publish regularly in order to keep an audience? Or are there strategies to maintain your momentum without impinging upon the quality of your writing?

Joe: Well, I think there is an expectation that websites should be updating frequently, like every day. I personally, as I've gone along -- and I think it's more difficult now, because the comics Internet has gotten a lot bigger in the last five years since I started writing on the Internet. It's easier to get lost, I think, now, writing about comics on the Internet -- to disappear into the crowd. So I think there might actually be more interest in writing more frequently. I've personally found myself slowing down, actually. I do write pretty quick, but I'm always writing something. I just don't stop, 'cause I don't want to. But some pieces, they overlap. I can spend two weeks working on something, and y'know, when it's posted it just appears, and it might as well have been made yesterday, 'cause I don't talk about how I write it. But yeah, those are factors at work.

Douglas: If you don't care about hit counts, though, it doesn't really matter. Once you publish something on the Internet, as long as you're paying for the website, it's there for good. You don't have to worry about distribution, you don't have to worry about it going out of print. If you have something to say and you publish it when you're ready, if you don't care about either hit counts or being supported by ads, it doesn't matter.

Sean: In my case, my blog is hosted on a site that was designed by a friend and some of his college buddies from Cornell to practice coding. So the hit count, y'know, the thing that monitors traffic is so rudimentary that it's useless. So I literally couldn't find out what my traffic was even if I wanted to. And that, over the years -- I really have never thought about having an audience. I've been blogging regularly, particularly over the last two years or so. I've been reviewing three comics a week, pretty much non-stop, and that's more for my own fun and benefit. I feel much worse about how rarely I contribute to Savage Critic(s), which I think...

Tucker: Yeah.

Sean: ...Tucker is part of and Joe and Douglas, because that's somebody else's site, and I know that they would like to get some traffic, and I just, I don't have it in me, for some reason. That I feel bad about, but on my own site, it doesn't really register.

Tucker: I don't know how anybody else comes at it, but I -- I mean, I haven't been at this but for maybe a couple years, and I always kinda treated what I do at my blog, at the Factual, as just like, it's my own school. I don't really know anything, I didn't take any classes in writing or anything -- it started as a hobby. And then other people... basically, Dirk Deppey linked to it, and then Tom Spurgeon linked to it, and then all of a sudden there was an audience, and it wasn't something that I really expected. I do try to follow a deadline, but that's basically because in my head I think, "Well, that's what writers do. They have deadlines to turn in pieces," or "They have deadlines to turn in columns." Then when ComiXology actually gave me money to write something, then I did have a real deadline. In my head, I'm like, "Well, if you have a deadline, then that's gonna... " It makes me write, it makes me do it. Like Joe, I just write about stuff all the time anyway, now that I do it and it's a hobby and it's fun. But it's kind of also a way to go, like, "Well, if you're gonna be a writer, you have to get stuff done by... " When I do my weekly comic thing, I do that every Sunday. That's what I do every Sunday night -- it has to go up. And there's an expectation there. But also, I just had an education this week: The most popular thing on my website, by far, is a review that my wife wrote, which is not really much of a review, it's just a personal reaction to Achewood, and that's because Chris Onstad linked to it. And if Chris Onstad links to something, then obviously that immediately becomes more popular than any review you write about any superhero comic or anything else, because a lot more people read Chris Onstad than read Tucker's jokey reviews of comic books. That's just the way it goes. So hit counts -- I don't even have ads, so I don't really care. It's like, "Whatever, that's not important."

Rob: For me, I only have a very vague idea of what audience I may have. But I read something, I think about it, and then I just feel a compulsion. I must write about it. And until I have written about it, the feeling doesn't go away. It's a very intense thing. And when people start sending you a lot of comics, just out of the blue [laughter from the panel], it's like, "Oh my God." All I think about is the backlog, thinking "Now it's time to read this." And then once I've done it, it starts the process, it starts the chain reaction until I've finished the review. And some books are harder to approach than others. I've been working on a review of the second Ivan Brunetti anthology thing for the last three months, and it's just not quite ready yet.

Gary: Can I ask you guys a related question to what Bill asked? I know most of you write for both print and the Internet. Maybe all of you do, but I know most of you do. Do you write differently when you write for print than when you write for the Internet?

Chris: Absolutely, yeah. Doug and I were just talking about this. I think you have to consider your audience and who you're writing to. When I was doing my column for the newspaper, it didn't matter if I was writing about Kazuo Umezu or Robert Crumb, I had to assume that most of the people who were gonna pick up that column were gonna have no idea who those people were, and I was gonna have to introduce them to this person. So half the column was easily going to be "Robert Crumb was this person who started in the '60s and did Zap Comix and now he has a new book out and it's good, the end." Whereas if I'm writing on Robot 6 or on my own blog or what have you, I don't really have to worry about that. I can assume that most people are all speaking the same language. I might, depending on the obscurity of the artist or the writer, I might do a little hand-holding sometimes for something like the "Collect This Now!" column that I do, where I kind of forge... I don't probably go into as much detail as I really should, usually 'cause I'm doing this late and night and I'm tired. But I do definitely consider who I'm writing to. The way I write for the Journal, for example, I bring probably a different attitude and way of writing than I do for some of the other reviews I do.

Joe: Yeah, and on an even more basic level, the Internet tends to be kind of a free-for-all, actually. So when I'm reacting to a book on the Internet, some of these things run upwards of four thousand, eight thousand words. In print, you just don't have that much space, and to make the thing read correctly, to get your ideas across properly, I've found that because I started on the Internet, I have to temper myself in order to get things within a certain hit count. Plus, I'm interacting with an editor who's looking at what I'm doing and sometimes will tell me, "Yeah, no one's gonna understand this." So I react to that, I interact with my editor, and that inevitably changes things, 'cause [when] I'm writing for my own site, I'm my only editor.

Sean: For me, it can be a print-web dichotomy, but it's also just the audience. The writing I do for the Journal, when I was reviewing for the Journal, obviously was a lot closer to my personal blog than if I'm writing online for Marvel.com or whatever.

Gary: I should hope so. [Laughter]

Sean: I'm not really doing criticism for them, but yeah, it's different. I also think that --

Gary: But the media themselves don't necessarily change how you...

Sean: Not really. Well, I mean, it really depends on the venue and their target audience. Douglas may be the only one of us who has the clout, in print, to write a bad review. In my experience, when I'm writing for a general-interest publication, they ask you, "What are some good comics coming out that we can cover?" So I'll pitch them stuff that I actually like, or think I'll like if I don't have a copy yet. So 99 times out of a 100 that I've written for Maxim, it's been about something that I'm excited about. I've barely ever given a bad review in print, except in the Journal, for that reason. Because they're not really... you know, usually the editors at general-interest publications who are running comics reviews are comics fans who are sort of boosters of the medium, to a certain extent, and they don't really want to waste real estate telling the audience why they shouldn't buy something.

Gary: So you're actually saying you need clout to get a negative review published?

Sean: I guess? I mean, I don't... [Laughs] [Douglas] is writing for magazines and publications that are a different kettle of fish than the ones I'm writing for.

Joe: It kind of depends on the forum. The general interest newspapers and magazines, they tend to take more of an advocacy position. I have written negatively for Bookforum -- they're a literary newspaper, though, so I think they're more inclined to treat comics like the rest of the books they'd review.

Douglas: Right. If you're writing for a large general-interest non-literary sort of magazine, if you're not writing about something that you're giving a positive review to, they're going to ask, and very reasonably, "Then why should our readers care?" I think, addressing your point about print versus online, one thing that is useful to keep in mind when I'm writing online is that print is maybe more suited to rendering some sort of judgment; writing online is maybe more suited toward opening a conversation, giving people something to respond to where I actually care about their responses, and they may actually care about each other's responses. I don't always manage that, though.

Gary: Does that change the way you approach the review itself?

Douglas: Um, it can certainly change the way I approach writing it. There's also the matter of the audience. If I'm writing for The Savage Critic, I'm writing for the people I saw in the comic store on Wednesday, and now it's Friday, and we're talking about what we saw on Wednesday.

Bill: That's interesting too. It does point out the value of venues like either The Comics Journal or Bookforum, in that if print is more suited towards rendering definitive judgments, and nine times out of ten print is also a positive advocacy slot, you're not going to frequently find in print the kinds of really thoughtful criticism that can actually maybe change the way that you think about things, necessarily. Right? I mean, [Douglas has] a lot of latitude at the Times, for example, and I think Joe and Dan [Nadel] and everyone else who's written for Bookforum has a certain amount of latitude there, and the Journal is all about critical latitude, I think. It's interesting, because someone wrote -- and I wish I could remember the writer's name... Well, Ng Suat Tong wrote a separate post on a similar subject, so I'll mention this one just because I remember the name, about Bottomless Belly Button, saying that he had read this book -- and he's someone who's written criticism for the Journal and other places. But he was responding more as a reader, saying that he had read this book and he wasn't entirely sure what he thought about it having read it. He went out looking for criticism that would help him refine his thoughts about it, expose him to other points of view, and found very little, even though there were many many reviews and things to link to. If that is a problem to some extent -- well, does anyone agree that that's a problem, that there isn't enough of this kind of thoughtful criticism out there for a reader who might be looking for this kind of material as a way to navigate the terrain? Or was it just a book that was underreviewed, or he wasn't finding it?

Chris: No, that was definitely not a book that was underrreviewed. [Laughter] I think that what you're getting is...

Bill: Well, maybe under-criticized, in a non-pejorative sense.

Chris: Yeah, well no, I don't even know if it was that so much as I think you're getting a lot of people who are coming at it with just that initial review. They're getting the book for the first time, and there's not a lot of going back to the book and reexamining it, or considering it on a deeper level. There's a lot of just that initial "Is this book good or not?" More review-ish.

Gary: But by the time he did that survey, the book had been out for about nine months. It wasn't like he did it three weeks after the book came out. It was pretty scary survey, I thought.

Bill: You saw this thing that I'm talking about?

Gary: Yeah.

Sean: But even online, you don't get a lot of... after the first couple weeks that the book comes out, nine months could go by and you don't get anything after that first wave. I mean, I'm skeptical about [Ng's] thing, but I'll...

Joe: That speaks to, I think, a potential downside of the Internet. Personally, I think there's an inclination, since there is no word count, there is no editor, to write short, to just get your impressions out, to just summarize, give what you think immediately about a book, you know, in five hundred, eight hundred words. Furthermore, there's no industry surrounding the Internet.

Douglas: The other thing there isn't is money. [Laughter]

Joe: Yeah.

Gary: But since there isn't any money, why wouldn't more thoughtfully considered reviews be just as good as a glib summary?

Chris: I think time.

Sean: Spending a lot of time for no material [gain], y'know, other than just the satisfaction of a job well done. And if you have to make a living as a writer, a lot of the time -- I mean, there's been times where I've been just like, "Well, I can do a freelance assignment that'll give me $100, or I can review a book." I've tried to keep reviewing books for free, but there's times when it's tempting just to take the $100 and run.

Joe: I agree with you, yeah.

Gary: This may sound like a preposterous question, but do you guys get paid for blogging about comics?

Chris: Yes.

Rob: No.

Tucker: No.

Joe: Sometimes. [Laughter]

Douglas: I think the Savage Critics have split ad revenues that have come in, and over the past two and a half years, it's amounted to maybe $18? [Laughter]

Bill: What did you get with it?

Douglas: I got a Diet Coke. [Laughter]

Rob: One of the downfalls of the Internet is a problem I had: I wrote something like 200 colums for Sequart, and then it died.

Bill: Yeah, and they're not there.

Sean: [gasps]

Rob: And they're not there, and you can't get to them.

Tucker: Gotta back it up! Back it up on the hard drive.

Rob: Yeah, I should have.

Sean: I don't even wanna think about that. Oh my God! [Laughter] It just occurred to me that that could happen! Oh my God! [Laughter]

Rob: The guy who runs the site says he's going to get all my old stuff and give it back to me. But I wrote a 3,000 word review of Bottomless Belly Button that I would have loved to have given to [Ng] and said "Yeah, I really thought about this book for a long time." But things can just disappear like that.

Bill: Tucker, you were about to say something?

Tucker: Part of it -- and I don't want to steal anybody's words, but this did come up when we were driving down here, because I rode with two of the people on this panel. [Laughter] It's part of the thing with Bottomless Belly Button, and I'll out myself for it: If you really really hate something, yeah, you might write some thoughtful piece about why you hated it and what's wrong with it. And if you really really liked something -- and I agree that maybe Bottomless Belly Button didn't get that treatment -- you might write something thoughtful. But if you're middle of the road, like, "I read it! I don't really give a shit! [Laughter] I don't hate it, but this is not gonna knock any of my 'Oh my God, this is what comics is to me' kinda stuff off the shelf."

Gary: But you shouldn't even be writing about something you're ambivalent about.

Tucker: Well, that's it -- then you don't. I don't write about Bottomless Belly Button.

Rob: Do you feel an obligation to write about...

Tucker: I think if anyone says they feel an obligation to write about something, that's totally self-imposed. Unless there really is an editor who's telling you what to put on your blog, there's no way, other than self-imposition, to write about something. Like, "Oh, I've gotta write about Asterios... " No you don't.

Sean: Yeah, Asterios Polyp.

Tucker: You don't have to write about Bottomless Belly Button, you don't have to write about David Mazzucchelli, you don't have to write about the latest development in Superman, you don't have to write about anything other than what the fuck you want to write about. It's not print...

Rob: I agree with you, but does anybody else feel like they need to be part of the critical discourse on...

Tucker: But what's that even mean? What's that even mean, though? [Laughter] Like, "the critical discourse." I mean, you go wide enough on the Internet, you're gonna find plenty of people... I mean, the classic thing for me is, you wanna see what's happens with the Internet, you go to the most popular YouTube video, and look at the comments on there, and everybody's just like, "THAT BITCH IS A CUNT!" [Laughter] That's the discourse of the Internet when you go wide enough. [Laughter] I really have to go to the bathroom.

Bill: You want to?

Tucker: Yeah. [gets up and leaves -- laughter]

Sean: Tucker Stone, ladies and gentlemen! [applause]

Bill: Tucker Stone will be returning momentarily. He's actually writing a blog post right now. [Laughter] A couple points I want to get to. Rob, I think you're coming from a very opposite position, because I think you actually make a good-faith effort to review everything that comes your way, right?

Rob: Yeah.

Bill: So you're definitely someone who's taken on an almost martyr-like constraint. [Laughter]

Rob's wife [from the audience]: As his wife, I agree! [Laughter]

Rob: When someone sends me something in the mail, I feel obligated to take a look at it and review it. What I have to say about it will vary. There were some things that were sent to me three years ago that I haven't written anything about yet.

Joe: Yeah.

Sean: Yeah.

Rob: But eventually I feel like I'll do something on it. And occasionally I'll do what I call a short-reviews column, where I'll realize, "I don't have anything more to say about this than a paragraph, or even a couple of sentences." As a critic, I feel that if someone sends me something, I should engage it as best I can, almost phenomenologically, just putting aside certain suppositions and ideas about a work. Which is why I review a fairly wide range of genres, with the exception of superheroes, which I don't write about. But I'll review minicomics, big publisher comics, children's comics, and each one of them sort of gets not a different critical response, but they're meant to be engaged at different levels, and I engage them in different ways. Yeah, I just feel a need to respond to that, to response to someone's work. And I rarely give -- what I actually rarely talk about is "Should you buy this?" I don't really care. I don't care. That's not something I ever say. Some critics even discuss, like, "This is a pretty good comic, but it wasn't worth the $20 pricetag," and that's a valid thing to say, but again, I don't care. It's not something I'm interested in. I just talk about the work, I engage it, and sometimes there's not much to engage, or sometimes there's an interesting idea but it fails in some spectacular way, and I talk about it on that level, and I go into detail, and it's a compulsion I have.

Bill: One issue that came up, too, is this notion of, "Do you need to participate in a critical discourse? Does everyone who writes need to weigh in on these big tentpole books that come out?" Obviously Tucker doesn't think so. [Laughter] And here he is. Welcome back, Tucker.

Tucker [returning]: That was off the charts, man. [Laughter]

Bill: Did you wash your hands? Okay. I think one of the things that's interesting to me about critical discourse is that criticism generates discourse, in that I don't know that it's necessarily required for every critic to write about the Crumb book, for example, but I also think it's possible for a very good piece of criticism about that to generate another piece of criticism. If a critic is identifying some quality of the book and either holding it up as praiseworthy or holding it up as a flaw, or identifying it as a virtue or the primary virtue or the point of the book or et cetera, I think that's the kind of thing that can probably generate a healthy critical discourse more than everyone feeling like they have to take a whack at the new piñata or whatever. Have any of you found yourself in that situation, where you've come across a book that you weren't necessarily motivated to write about, but some other writer's take on it motivated you to respond or reconsider something? It's probably hard to remember, so I'm asking a horrible question. [whistles]

Gary: I think that does sort of answer Tucker's question, though, which is "What the fuck is that?": Critical discourse is a public dialogue about what's going on out there, what significant works are out there, what do they mean.

Tucker: Yeah, but that's -- yeah, I agree with that. What I disagree with is -- the notion that there's a real public dialogue that comes about because a bunch of critics wanna do what he's talking about, they wanna respond to real criticism and they wanna create some criticism of they own.

Gary: You don't think that that exists?

Tucker: No, I do agree that that exists. Like, earlier this year, when, um -- like, these three right here [gestures to Sean, Joe, and Douglas], you know? When Final Crisis dropped.

Sean: Oh yeah.

Tucker: Which is like, it's a superhero masturbation-fest, but still. [Laughter] That was really fascinating, to see all these different takes, and to see people genuinely come out of the game and really put out there stuff there. But they didn't feel -- I don't think that you'd turn to Sean and be like, "Did you feel imposed upon?", like he had to respond to Final Crisis. He wanted to. Joe wanted to. When stuff comes out, it's up to the art to create that desire in people to actually go and respond to it. If it's created from some feeling of, "Well, I'm obligated to write about this, so that there will be a public discourse... " The art creates the public discourse, not --

Gary: Of course.

Tucker: It shouldn't come from some feeling of, "I'm obligated to help create this so that comics can have its own little critical discourse." It's up to the comics. It's up to them.

Joe: I think it happens with superhero comics. There tends to be a lot more, I think, discussion about those on the comics Internet because there's a certain volume of superhero comics that comes out every week, every single week. And superhero comics today are attuned to giving this impression of a shared universe that you peek into every week and see how things do or do not interact. So I think that has a way of encouraging more people to talk about these things often, and there's inevitably more dialogue about a superhero thing that a lot of people happen to want to talk about, like Final Crisis. There's more support.

Douglas: I don't think of it as an obligation, though. I think of it as a pleasure.

Joe: Well, yeah. But there's just more things to react to.

Douglas: Sure.

Sean: I see what [Joe]'s saying, though, 'cause I think Final Crisis gives you a good apples-to-apples comparison. I loved Final Crisis to pieces, and I loved talking about it, and I loved reading people talk about it even when they hated it. But Acme Novelty Library #19 came out in roughly that same time frame. It is not just the best comic of the year, in my opinion -- it's a terrific science-fiction story, it's a terrific horror story, you could talk about it in genre terms if you wanted to, which is the kind of thing I like doing. But there was none of that back-and-forth that we had going about Final Crisis. And I will defend Grant Morrison and Final Crisis until the day I die, but I would have loved to have -- and I said so, I think -- I would have loved to have that much writing, just that volume of people writing these huge impassioned posts, about Acme Novelty Library #19.

Gary: Well, why didn't that happen?

Sean: Well, I think there's a bunch of reasons. He's been so good for so long that that people run out of things to say about how good he is...

Gary: And that's not true of Grant Morrison? [Laughter]

Sean: Well, I guess -- 'cause Morrison is like "the literature of ideas," and he's beboppin' and scattin' all over the place, so there's always specific things to talk about.

Douglas: He's a lot less consistent than Chris Ware, too.

Sean: That's also true. There's stuff you can compare that you didn't like by Grant Morrison. And it's also very bleak, and Acme Novelty Library might be the bleakest thing he ever did. I feel like that turns a lot of people off, and they just don't feel like they have an "in" to it.

Joe: But I think it is a different situation, though, because Acme #19 is a serial, and unless you've been following Chris Ware's thing for however long ago he serialized this in the papers, it doesn't compare to something like Final Crisis, where it's the lynchpin of the DC Universe. I don't think it works like that, but --

Sean: But I'm not even talking about the people who just --

Joe: I'm saying there's inevitably going to be more conversation, because people are going to want to talk about it even if -- because it effects other things in the superhero world.

Sean: But I'm not really paying attention to those guys. I'm talking about people who... [sighs] They're not just being like, "What did Wolverine say this week? He would never say that!" [Laughter] I'm not talking about those people. I'm talking about people who treat comics as art, and yet don't... I'm sorry.

Douglas: If we're going to be apples-to-apples about serials, though, you might have seen more of that if, you know, Acme were monthly. [Laughter] Dream on, but...

Rob: Honestly, it's easier to talk about Final Crisis than it is to really sit down and think for a long time and think about Chris Ware's Acme #19. The other thing I've noticed about superhero comics is that it's almost akin to people talking about their favorite football team, and what has happened to their football team that week.

[murmured assent from the panel]

Sean: Yeah, Tim O'Neil had a thing about that recently.

Rob: There's this kind of weird emotional investment in it that's difficult to put apart from a critical analysis. And to me that's kind of the culture of way more mainstream superhero criticism. I know there's a lot of folks who do both, but there's also many, many, many more folks who only will review superhero books.

Sean: Yeah.

Joe: Yes, yes.

Rob: And it kind of creates a certain kind of clubby thing with their writing. Which is why it's interesting -- a question I've asked a lot of you guys is, do you approach reviewing superhero comics and art-comics any differently? How does that work for you?

Sean: I'm sure that I do, but...

Chris: I really try not to, whenever possible.

Rob: Not to do it differently?

Chris: Just approach the work on its own terms and on its merits. I mean --

Bill: Well, if you say on its own terms, though, that suggests something different.

Chris: Well, yeah, I was about to say, yeah.

Bill: 'Cause you're not judging the Whatever Crisis the way you would judge the Chris Ware, necessarily.

Douglas: If you're judging something as part of the giant interlocking master narrative, like, yeah, that's obviously going to come into it. And that's part of the fun of reading it and that's part of the fun of thinking of it. It's also really fun to deal with superhero comics on the same terms that you would deal with art comics. But it can sometimes be hard to get away from the fun of thinking of, like, this window on the master narrative.

Bill: But there's a different focus, certainly, right? Because when you're talking about Chris Ware, you're talking about someone as an author or an artist making a work, whereas when you're looking at this other stuff, you're kind of looking at this sort of collaborative project.

Douglas: Well, you're thinking of it as an author and artist, partly, making the work also. But there's also this other part to it.

Sean: Yeah. I don't treat that any differently.

Gary [to Bill]: You're saying Grant Morrison isn't an auteur?

Bill: Well, maybe, I don't know. He has a chapter in Douglas's book, so the answer is yes. [Laughter] Tucker, this is something you had talked about, too. Putting aside the superhero/auteur-driven work, whatever, you were also talking a little bit about, do you -- [Tucker fidgets with the tablecloth on the panel's table] Don't play with the Velcro.

Tucker: You're the one who knocked it off, man! [Laughter] C'mon, playa!

Bill: Sorry. But bringing different expectations to different work -- like if there's something by a young, twentysomething first-time cartoonist, handling that a little different.

Tucker: Yeah, I have to admit that that does... Like, I'll read some minicomic or something where I've met the person, you know? Some 19-year-old kid who's shy and is like [quietly] "This is my minicomic" and that sort of thing -- I really don't look at that and go, "Well, okay, you're some 30-year-old in the business and you're published by Fantagraphics which means you're probably not some first-timer." Yeah, that stuff, it gets a little -- I mean, I try not to do that, and most of the time what I do is I just don't review it, because it's hard to read something by some kid. Like a kid, a fucking kid! [Laughter] Who's just getting started! And to be like "Yeah, this is trash!" You want to sit there and go, "Well, I really see some promise." I don't see any promise! I want you to stop! [Laughter] I mean, you should go to college! Learn a trade! Because you're not gonna be Chris Ware. You're not even gonna be Tony Bedard, you know? [Laughter]

Rob: I've been reviewing comics lately for the Poopsheet Foundation website, and --

Tucker: Poopsheet?

Bill: Poopsheet.

Chris [in a dramatic voice]: Poopsheet? [Laughter]

Rob: Let's all get it out. [Laughter] And these are things sent to the guy who owns the site who then sends it to me, as opposed to some of the other comics I get. 'Cause people who send me stuff have a general idea of what I'm going to say about comics, or comics in general. These people don't know that I'm going to be reviewing it. And the quality of the comics I've been getting from this guy have been measurably worse, and I've said some of my harshest stuff. And again -- but it's the same approach. I hear what Tucker's saying, like "there's a young kid," and I see a lot of comics like that, where it's like, "Well, you know, it's overwritten, it's overdrawn, but maybe there's something here and maybe there's not." But there are some where it's just like, "This just wasn't a good thing to read."

Gary: You can ignore them, if they're not somehow significant.

Rob: Yeah. And hopefully the feedback is useful to them in some way, in saying, "This is the best I could do, or maybe it wasn't, and it just wasn't good enough." And maybe it'll spark some kind of response. But I don't feel any obligation to think about what their response will be.

Gary: Right.

Rob: You can't.

Gary: You can't, right.

Sean: I got a lot of my scorched-earth criticism out of my system in the early days of the comics blogosphere and a couple things I did for The Comics Journal. I don't really have that in me anymore, and I find myself not enjoying reading it too much, either. But one thing that I've brought up before on my site or in interviews is that all the reviews I do for my own blog, I do from my own spare time, and they're generally books I'm interested in reading, so it's sort of a self-selecting group. Like, if I flip through something, and it doesn't look appealing, or it looks downright aggravating, you know, there's only so many hours in a day, and I'm generally not gonna force myself through something that I don't think I'll get to the end of it and say, "Well, that was a valuable way to spend my train ride" or whatever. So to a certain extent, that's not a problem for me, because if I get something and I'm like, "What am I gonna do, tear this apart?", I just won't.

Tucker: Well, I'm not gonna try and back off or anything like that. [Laughter] But I will say that I don't ask for free shit and I don't get free shit, so when some kid sends me something, I usually read it. And I'm talking, what, two fuckin' minicomics a month, you know? I'm not sitting there, I don't have some kind of hookup or anything like that. I basically read what I read and then review that. But when I do get something in the mail from some kid -- which it's always fucking kids! I don't know why -- it's like they don't read the blog or something like that. It's not like I have some big post on there where I'm like, "Aren't minicomics awesome? Can I read more about your parents?" [Laughter] That's the shit that I get sent! I get sent 8 X 11s stapled at the top corner. That's what I get sent. I don't know why they send it to me, I don't know who told them to do that, but that's they send.

Bill: There's some grade school teacher somewhere who found your address.

Tucker: Somebody! Somebody.

Bill: Gary, Sean was just talking about how he's not as interested in negative critiques --

Gary: A little sad! [Laughter]

Bill: But the Journal has actually run some of the outstanding negative critiques in the history of this field. How would you articulate the value of that kind of criticism for someone who maybe finds it difficult to approach?

Gary: Someone for whom it's difficult to read?

Bill: Yeah, maybe, or who would balk at writing something like that.

Gary: Well, I don't feel like you should write it just for the sake of writing it. But I think as a critic, you have to run the gamut. You just have to give an honest response. And sometimes that honest response is going to be negative. And, I mean, that serves the function of critically dismantling something that might be a sacred cow or that might be widely reviewed and widely praised and offering readers an alternative point of view about that, and allowing them to think about it in terms they haven't even seen before. I mean, I just think that has an intrinsic value.

Rob: To me, the danger is that you can never make a negative review personal, to me. At least that's my philosophy. Which is why I hate really snark-heavy negative reviews. [Various panelists turn to look at Tucker -- Laughter] Because to me it's just kind of a dishonest reaction. That's just my personal thing. You can talk about the weaknesses of a work as the work without necessarily attacking an author or a person. And you can get really really negative about it and talk about "This is why this doesn't work." And the responses to some of that that I've had have been, some people have been... I've written some harsh things and people have said, "Thank you for the review, that was very helpful," and I've written some minorly harsh things and gotten really negative feedback. I'm like, "Well, that's just the way it goes," but in neither case did I say, "This is awful, this person should never write again" or anything like that.

Douglas: My allegiance as a critic is always to the people that are reading what I'm writing, not to the person making the art. But there's a lot of art that I'm exposed to that leaves me so cold or bores me so much that I don't get all the way through it, and I can't see the value in writing scorched-earth something about that unless there's a way that it can be a gift for my reading audience.

Bill: A gift in terms of food for thought as opposed to just dismissing a work that you thought didn't have any merits?

Douglas: Yeah, something that can be useful or meaningful or something to the people reading it.

Bill: Alright, well, with that we're basically out of time. But I guess I could probably take one or two questions, if anyone has... yes?

Audience Member #1: I have a question. If you -- like, I listened to the discussion -- Is there a proper venue to go through to get a good critique? [Laughter]

Bill: What's the best place to get a good review?

AM1: Yeah -- no, not, like, "a good review"...

Bill: Do you have any friends with blogs? [Laughter] No, no.

AM1: I mean, I heard you [Tucker] say you get like two little minicomics a week or something -- is there a submission...

Sean: No, just find a blog that you like -- I mean, it just comes from reading different sites or different publications and getting a sense for their tone, and if you feel like you'll get something valuable out of being reviewed by this person, drop them an email and say "Hey, I'd like to send something."

Rob: Go to The Comics Reporter website and Journalista! -- they do a zillion links to reviews. Find someone whose work is interesting to you and that you think would be appropriate and contact them.

Bill: Yeah, almost every blog or whatever, review website, has some kind of email link, and if the mailing address isn't on there, people will usually send it to you if you ask them to.

Sean: Unless it's NeilAlien, people will take review copies and thank you for it.

Audience Member #2: Have you ever changed your mind about something, either positive, liked it and then didn't like it, or didn't like it and then liked it, and felt you needed to really let people know that?

Sean: I wrote a very negative review of Locas, the Jaime Hernandez hardcover, in The Comics Journal, and I have completely changed my mind since then. [Laughter] And I'm waiting until I have a chance to sit and read everything in a row and write a new review, and I'll run the old review one day and I'll run the new review the next day and be like "I was totally wrong."

Chris: You have to. If you're gonna review, and you're gonna be a critic, you have to face the fact that you may change your mind and you may change your taste as you go along.

Tucker: I actually reviewed Essential Fantastic Four, one of those black and white reprint books, the day before my wedding. [Laughter] I don't know why I reviewed it then, but I was just like, "Man, fuck this book," you know? [Laughter] "I like Kirby, but fuck black and white reprints. Five-hundred page -- this is retarded!" [Laughter] Then Frank Santoro was like, "Man, you're just freaking out because you gotta get married tomorrow." I was like, "That's right!" [Laughter] I got back from the honeymoon and I left it up there, but I was like, "I should probably fix that. That was a stupid thing to do."

AM2: Not necessarily "fix it," but just kind of...

Tucker: No, fix it.

AM2: Oh. [Laughter]

Bill: One more --

Audience Member #3: Where do you guys see a role in arts criticism in general, and how would you compare some of the ways you engage with the work with music writers or fine-arts critics?

Bill: Anyone immediately wanna jump on that? I know Douglas, you write about music.

Douglas: I can talk to you about this afterwards, but yeah, I... I can't answer it easily. [Laughter]

Bill: Well, with that, please join me in thanking all of our distinguished panelists for being with us. [Applause]