In 1992, Image Comics' "Spawn" #1 opened with a mysterious figure stalking the Manhattan rooftops, musing on the nature of life and death. His past was largely a mystery, but this didn’t prevent the comic book buying public from embracing the new anti-hero. Not only would "Spawn" break sales records for its debut issue, it would consistently outsell almost every comic released by Marvel and DC, often ranking as the highest selling title in the market, period. Even after the speculation bubble burst, and the hysteria that surrounded its publisher died down, the book doggedly held on to its audience for the next decade, generating spinoffs and miniseries, soon expanding beyond its four-color roots with an action figure line, an HBO series and a live-action film.

The dawn of the new millennium saw "Spawn" remain a Top 10 title, although you wouldn't know this if your only exposure to fandom were online comics sites. In spite of its popularity, and the celebrity status of creator Todd McFarlane, "Spawn" carried with it a critical disdain that would always be difficult to shake. And when fandom shifted away from "Wizard" magazine to the more elitist cliques of online message boards and fan sites, "Spawn" began to see its star dwindle.

The book still sold respectably into the 2000s, but most online comics discussion was centered on the latest event comics, new critically acclaimed creators, and a handful of unpopular mainstream titles that fans just loved to hate. In fact, one of the comic review sites that debuted during the dot-com boom briefly attempted to review "Spawn"...and actually felt the need to explain why they were doing so when covering the first issue. This was a book with a loyal audience, respectable (if sliding) sales, and nearly ten years under its belt. But discussion of the title online was so rare, the reviewer actually felt compelled to explain why it might be worth covering.

Even if the mainstream comics Internet didn't care that much, "Spawn" marched on throughout the new millennium. Occasionally, a new creative team was announced, generating some publicity (like when horror writer David Hine took over the title, or when Image co-founder Whilce Portacio became penciler), but those moments were rare. This was a book that was consistently under the radar -- no longer a top title in the industry, but still one of Image's higher-selling titles, and the rare publication that refused to ever restart its numbering.

The renumbering gimmick was one tactic that McFarlane was occasionally asked about in interviews, and his stance never wavered. McFarlane saw everyone else try the stunt, tossing away their title’s acquired history for a brief sales bump that never seemed to accomplish much in the long term. Why would he do this to his own creation? McFarlane's argument made sense; but it also hinted at another limitation faced by "Spawn." Any other superhero title that's lacking "buzz" will likely see the company swap out the creative team. McFarlane's loyalty to "Spawn" is admirable, but in terms of publicity, it's a nightmare. How does a publicist attract attention to a book by boasting that the same person who's worked on most of the issues is still there? That's not how the news cycle works. (McFarlane's so devoted to the direction of "Spawn," he even spent a few years writing it under a pen name, just to create the illusion that some new blood had been brought in.)

Visually, McFarlane was also a victim of his own success. The early issues of "Spawn" contrast the dark elements of the series with McFarlane's charming cartoon style, creating visuals that the audience had never experienced. The guy who drew that bug-eyed Spidey and foxy Mary Jane? He also liked to draw vicious demons from Hell eviscerating mobsters, using their internal organs as objects of sport.

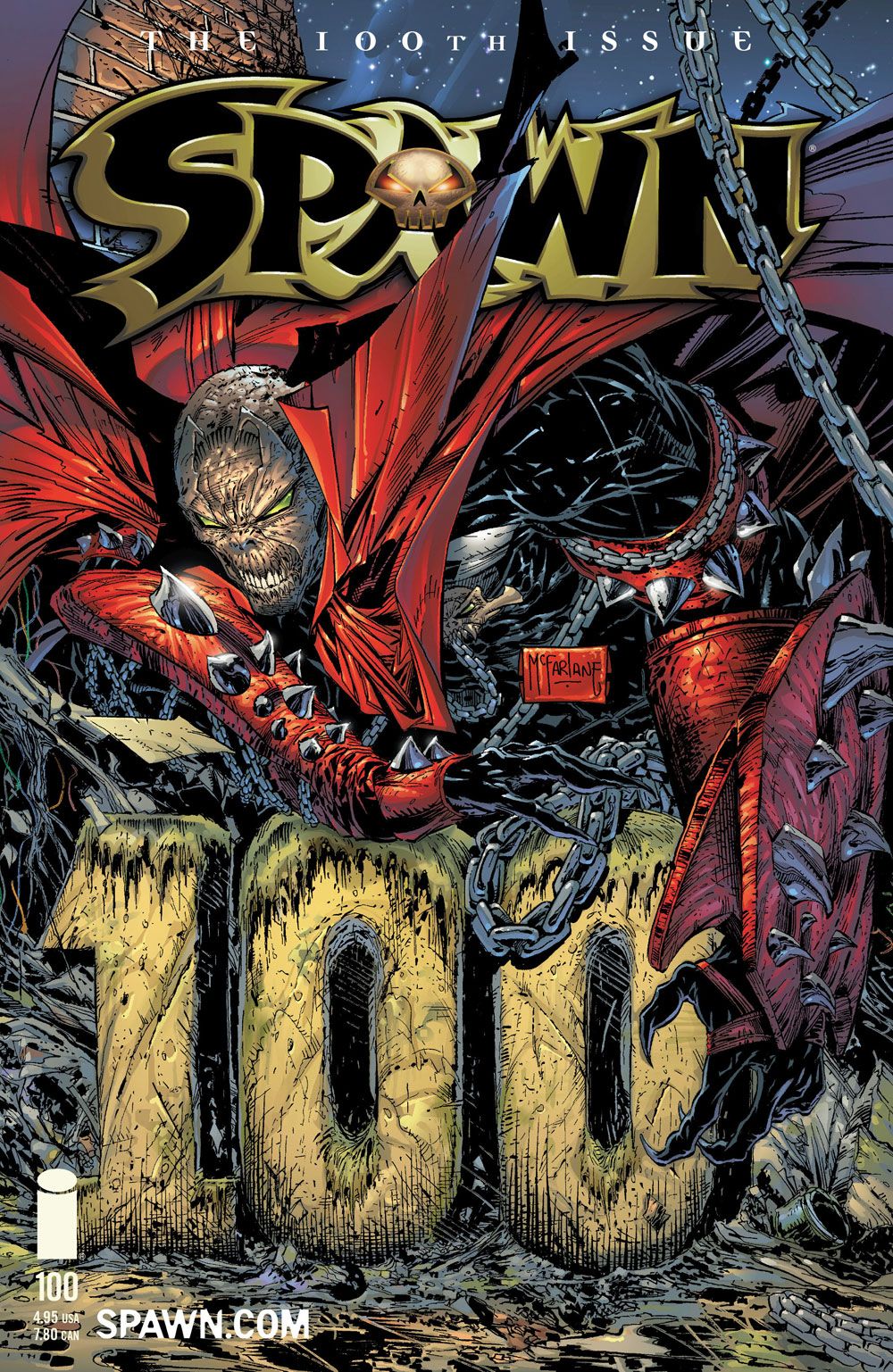

The dichotomy between McFarlane's soft cartooning and his ridiculously detailed blood and gore was irresistible to the average twelve-year-old comics fan. A few years into the run of "Spawn," McFarlane was joined by popular "X-Force" penciler Greg Capullo, an artist McFarlane acknowledged as his technical superior. With McFarlane and Capullo joining forces, a "Spawn" house style emerged: shadows everywhere, but any object the light touched would be covered with copious detail lines. Everything had to have texture in "Spawn," as the playful cartooning of the earlier issues gave way to a grimier, more twisted look.

This was a style embraced by the most hardcore "Spawn" fans, but following Greg Capullo's departure from the book, casual readers began to drift away. Every "Spawn" cover seemed to look the same, depicting the grim anti-hero humorlessly posing in front of a handful of backdrops (church rooftops, graveyards, a spooky forest, etc.) As the X-Men titles hired artists ranging from Joe Madureira to Adam Kubert, and Superman went from everyone from Steve Epting to Ed McGuinness, "Spawn" stubbornly stuck to its house style. And while any of these corporate-owned superheroes could've easily been called in to participate in a line-wide crossover whenever sales happened to dip, "Spawn" was left as one of the few remnants of the nearly dead Image Superhero Universe. There was the occasional acknowledgment in "Savage Dragon" that this guy Spawn was out there, but that was essentially it.

"Spawn" remained a book that wouldn't, or couldn't, engage in the typical tactics used to keep a title alive. Todd McFarlane remained in the public eye, but mainly due to his successful toy empire and occasional collaborations with music stars and various celebrities. McFarlane, a lifelong admirer of "Cerebus" creator Dave Sim, was always keeping the back catalogue in print, however. Even if twelve-year-old boys were no longer spending a lot of time in comic shops, those "Spawn" reprint collections were always around in bookstores. Older comic fans were increasingly indifferent to the book, but new readers were discovering "Spawn."

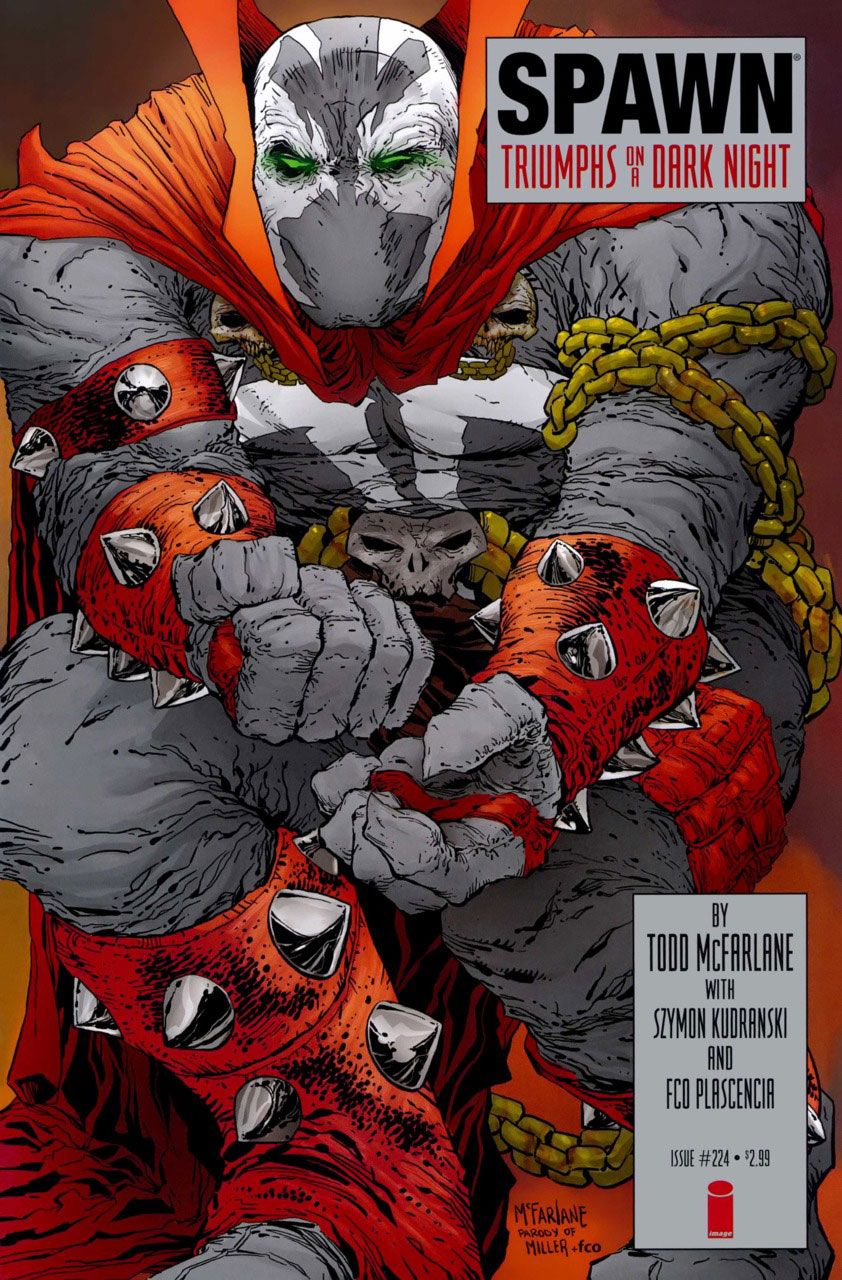

By 2012, the lack of press on the monthly "Spawn" title was perhaps getting to McFarlane. After years away from the covers, McFarlane announced that he would be coming back as a special engagement. And he brought along with him something the audience rarely saw on a "Spawn" cover -- jokes. Archived on the Miscellaneous Pile blog page (here and here), the run of parody "Spawn" covers not only highlight McFarlane's sense of humor, they provide readers with a break from the relentlessly grim "Spawn" images that have been so dominant since 1992.

The parody cover series perhaps didn't set the world ablaze, but it did revive some interest in the monthly title. For at least a few months, "Spawn" wasn't the same ol' cover staring back at you from the racks. There was actual personality there, not to mention something '90s comics fans rarely saw anymore -- McFarlane pencil art.

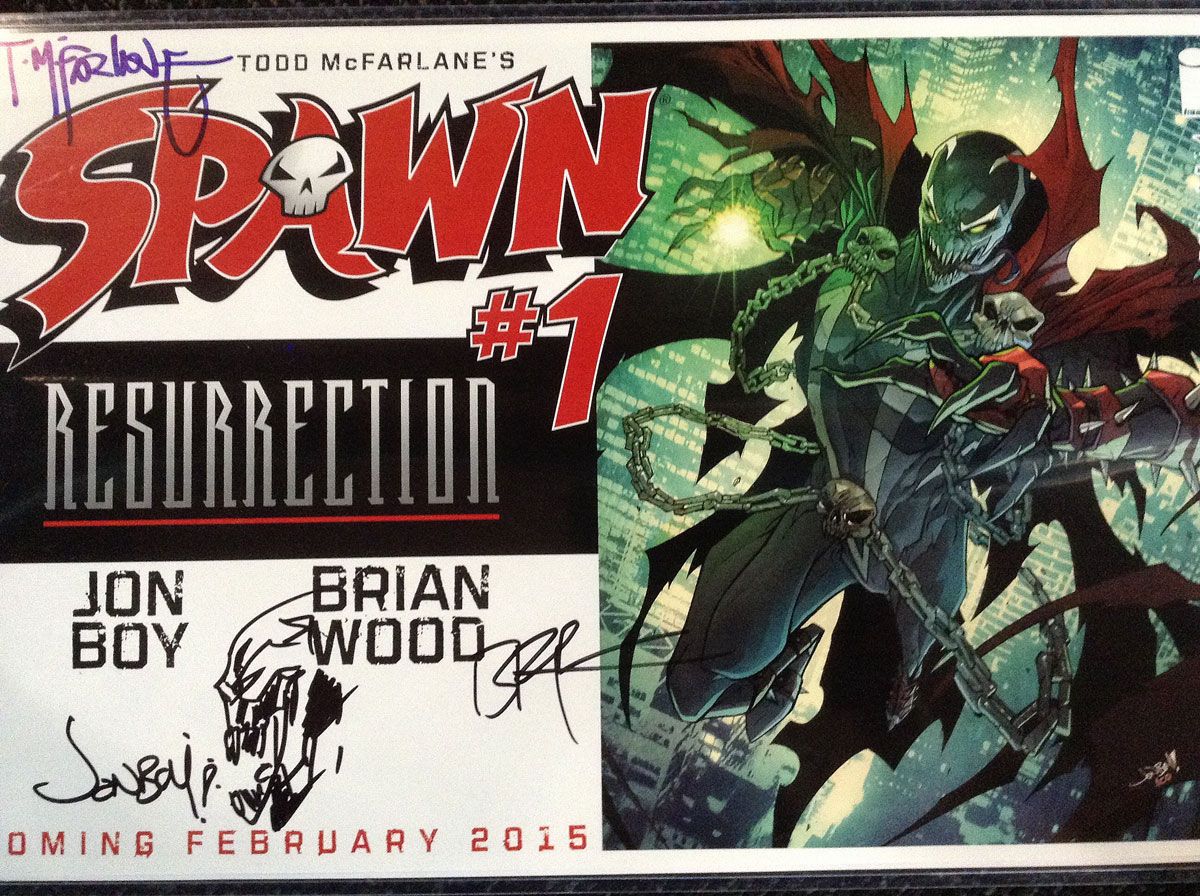

As the book approached its 250th anniversary issue (an Image landmark, and a true rarity for an independent comic), McFarlane looked for other ways to revive interest in his series. He announced the revival of the comic's original star, Al Simmons, swapping out the replacement character Jim Downing who had taken over the book years earlier in an effort to shake up the title. Artist Szymon Kudranski had been brought over by then, moving the book away from the McFarlane/Capullo house style and closer to the Photoshop-enhanced realism seen in a number of modern comics, but a major change in creative teams hadn't happened on "Spawn" in years. Realizing that this was an opportunity to seize some headlines, McFarlane decided to bring some new names on to the title (at one point, even attempting to lure Grant Morrison onboard), and to do something he vowed never to do. Almost.

"Spawn: Resurrection" was solicited as having an all-new creative team, and a new direction for Spawn. It was also going to be the long-requested "new #1" relaunch for the series... except McFarlane had no plans to actually renumber the book. "Spawn: Resurrection" was a one-shot with a big #1 on the cover, giving readers an excuse to buy a new "Spawn" #1, without rebooting the main title. Following "Spawn: Resurrection" #1, the story would then move to "Spawn" #251. The announced team, critically acclaimed writer Brian Wood and the manga-inspired Jonboy Meyers, went on the requisite publicity rounds, promoting all of their great ideas for the title. People were talking about Spawn again, and for good reason. A new, respectable creative team, a clear jumping-on point for new readers, and the burgeoning wave of '90s nostalgia all meant that "Spawn" had a decent chance at regaining momentum.

The "Spawn" relaunch was a bit rocky, however. Brian Wood dropped out of the project not long before "Spawn: Resurrection" was released, with Paul Jenkins being called in as a last-minute replacement. Jenkins has a history with Spawn, having written one of the spinoff titles during the final days of the character's commercial dominance. Jenkins, during his initial stint with the character, had attempted to address an issue that always plagued McFarlane's creation -- what's this guy's motivation? While Batman fights crime to avenge his parents' death, and Superman exists as an alien raised with traditional American values, sticking up for the little guy, what drives Spawn to ever do, well, anything?

The traditional premise of the series leaves him without a reason to ever leave his home in the alleys. His only love interest is his wife, who is now married to his best friend. Spawn's skin is rotted flesh, so he's unable to interact with the general public. His only friends are a cluster of homeless men who view him as some sort of king, and mainly exist as punching bags for Spawn whenever he's in a mood. Spawn occasionally runs afoul of agents of Heaven and Hell, and the random mobster or crack dealer, but he has no drive to do much of anything. He's not particularly heroic, and not engaged with the world around him. How do you get stories out of this premise?

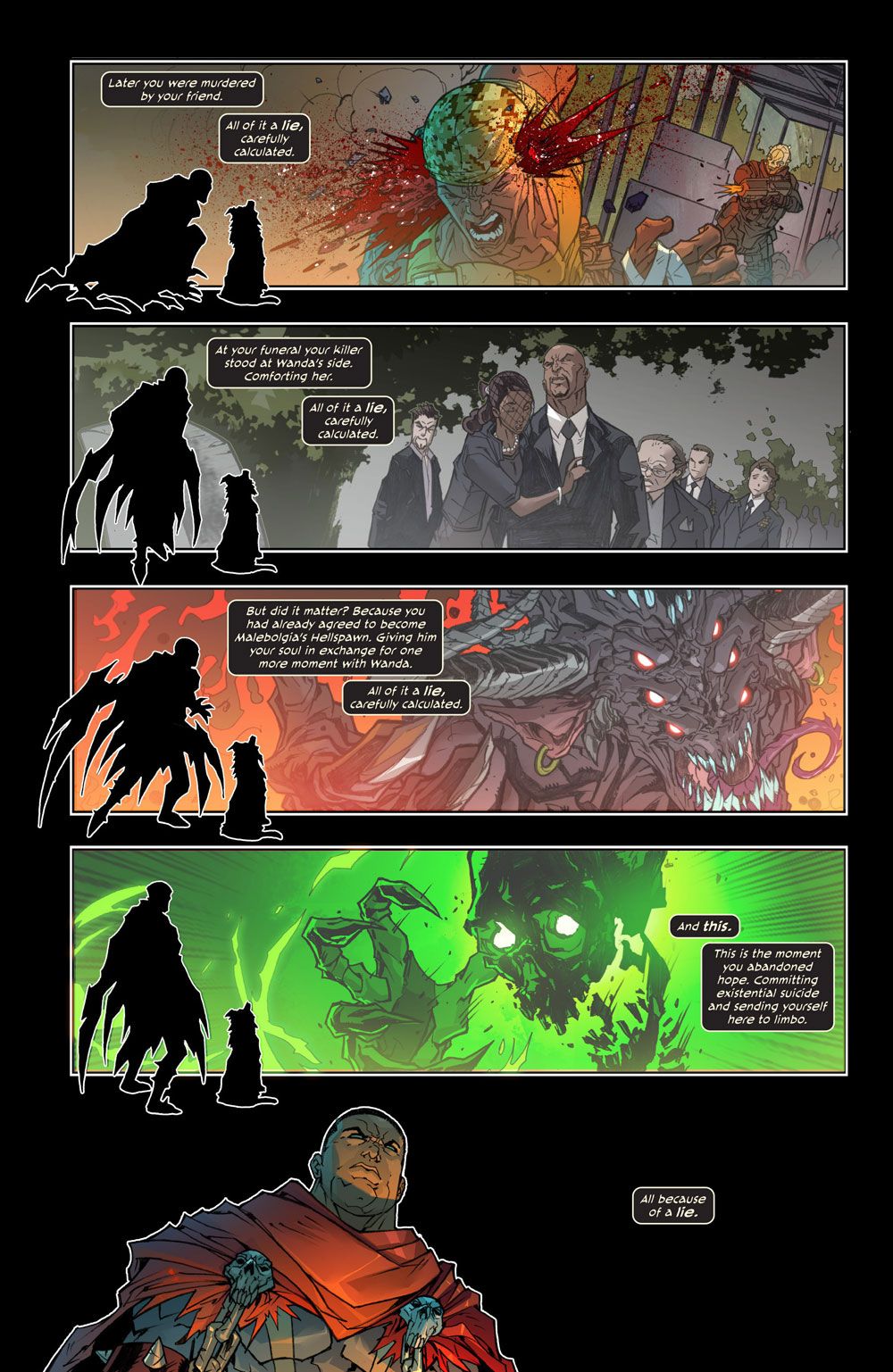

"Spawn: Resurrection" works on the assumption that the reader is familiar with a 1992-era Spawn and little else; the implicit understanding from its opening pages is that it's a comic for lapsed readers, and everyone's invited to come back. The book disrupts the traditional status quo of "Spawn" within a few pages, when we discover that his long-coveted wife was killed during a political protest. Spawn, trapped in a void between life and the afterlife, is greeted by a talking dog who claims to be God, spelling out the new driving force for the series: There's evil in the world, and it's killed your wife, who's now searching for the soul of your unborn child. Spawn then agrees to a new deal, this time with God and not a devil -- he'll fight evil on Earth, with the understanding that he'll be reunited with his wife and unborn son one day.

Jenkins cited a desire to continue this new direction in the monthly title, with each issue sending Spawn on a specific mission while the narrative attempted to dig deeper into the lead character's psyche. This was not to be. Jenkins' run on the title concluded in #254, and with every issue carrying an additional writer credit for McFarlane, it's natural to assume that McFarlane was having a hard time letting go of the series. The next few issues saw McFarlane attempting to carry on with the story arc with Jonboy Meyers, whose bold caricatures bring to mind what the "Spawn" series might've been had McFarlane snatched Joe Madureira from Marvel circa 1996. Meyers' style of cartooning evokes the earliest issues of the series, and strikes a nice balance between the darker elements and the basic absurdity of the title. Unfortunately, he didn't stick around much longer than Jenkins. Szymon Kudranski was back with McFarlane as of issue #256, as McFarlane set up a new storyline that would see Spawn travel to Hell for an epic battle.

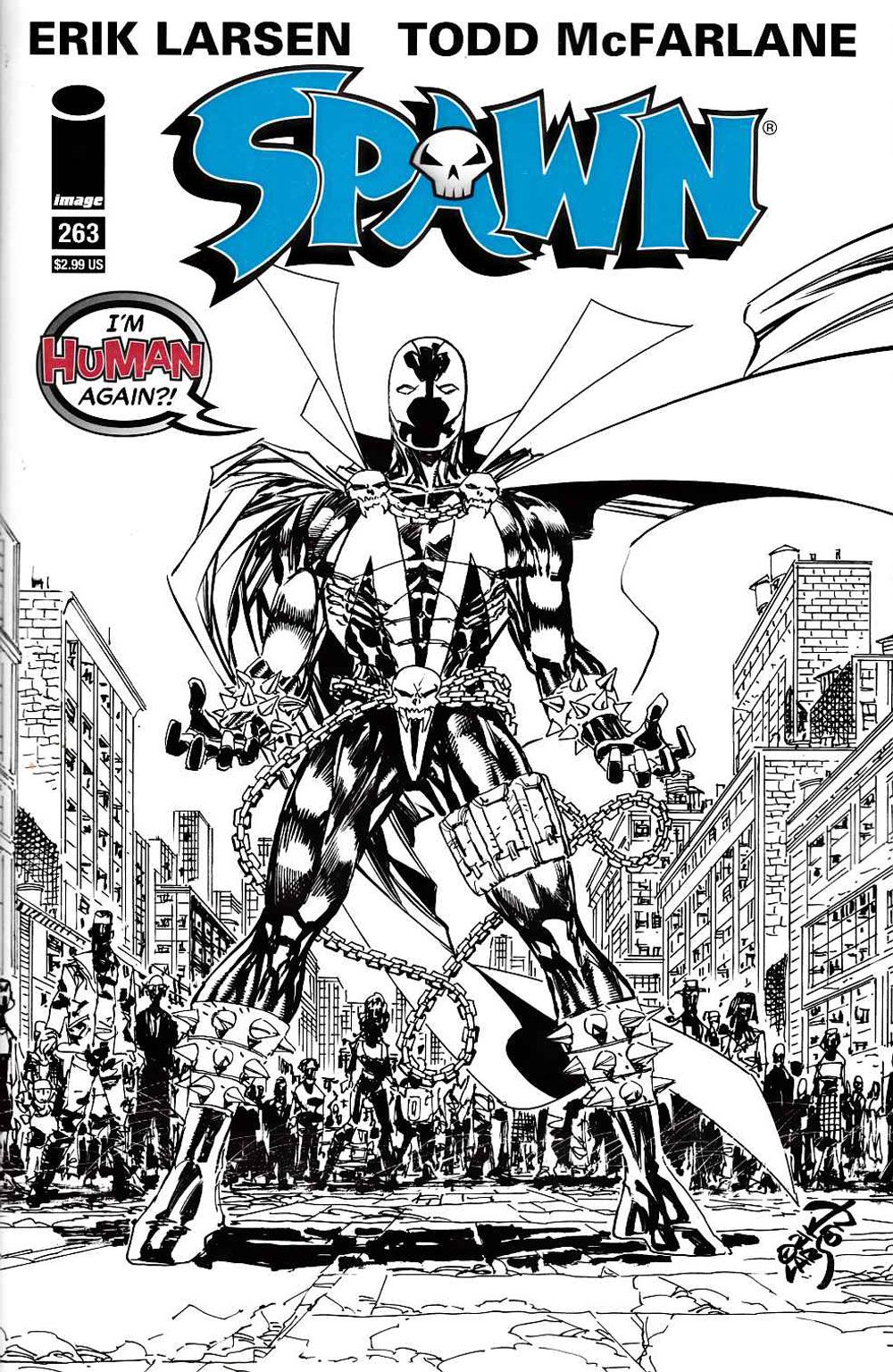

"Spawn" #258 was intended as the start of another brave new era for the series. Todd McFarlane was now joined by Image co-founder Erik Larsen to begin an action-packed direction. After years of Spawn skulking in the shadows, the threat of Hell a vague whisper of a potential end-times conflict, the series was now presenting Hell via Jack Kirby, with page after page of Spawn in action, fighting one ridiculous demon design after another. The new method for creating the title would see Erik Larsen working out the plot with McFarlane, Larsen providing the pencils, and McFarlane finishing the book off in his unique inking style. It's a collaboration that fans of a certain era only caught brief glimpses of in "Amazing Spider-Man" pin-ups, or the occasional Image special project. To say that Larsen's approach to comics differs from McFarlane's is an understatement; while McFarlane had settled into the idea of "Spawn" as a slow-moving suspense comic over the years, Larsen leans towards action and insanity.

Following several issues of Spawn facing Satan and his minions, the status quo was given another update. Spawn is reunited with his wife, who makes it clear to her husband that she can't return to Earth. And even though they can't be reunited in the afterlife today, she asks him to return home and fight in her memory. "Be a hero," she tells him before being sent to Heaven, and Spawn agrees. So, for the second time in two years, Spawn's motivations are given a tweak. He's now on Earth to honor his wife's memory and fight evil.

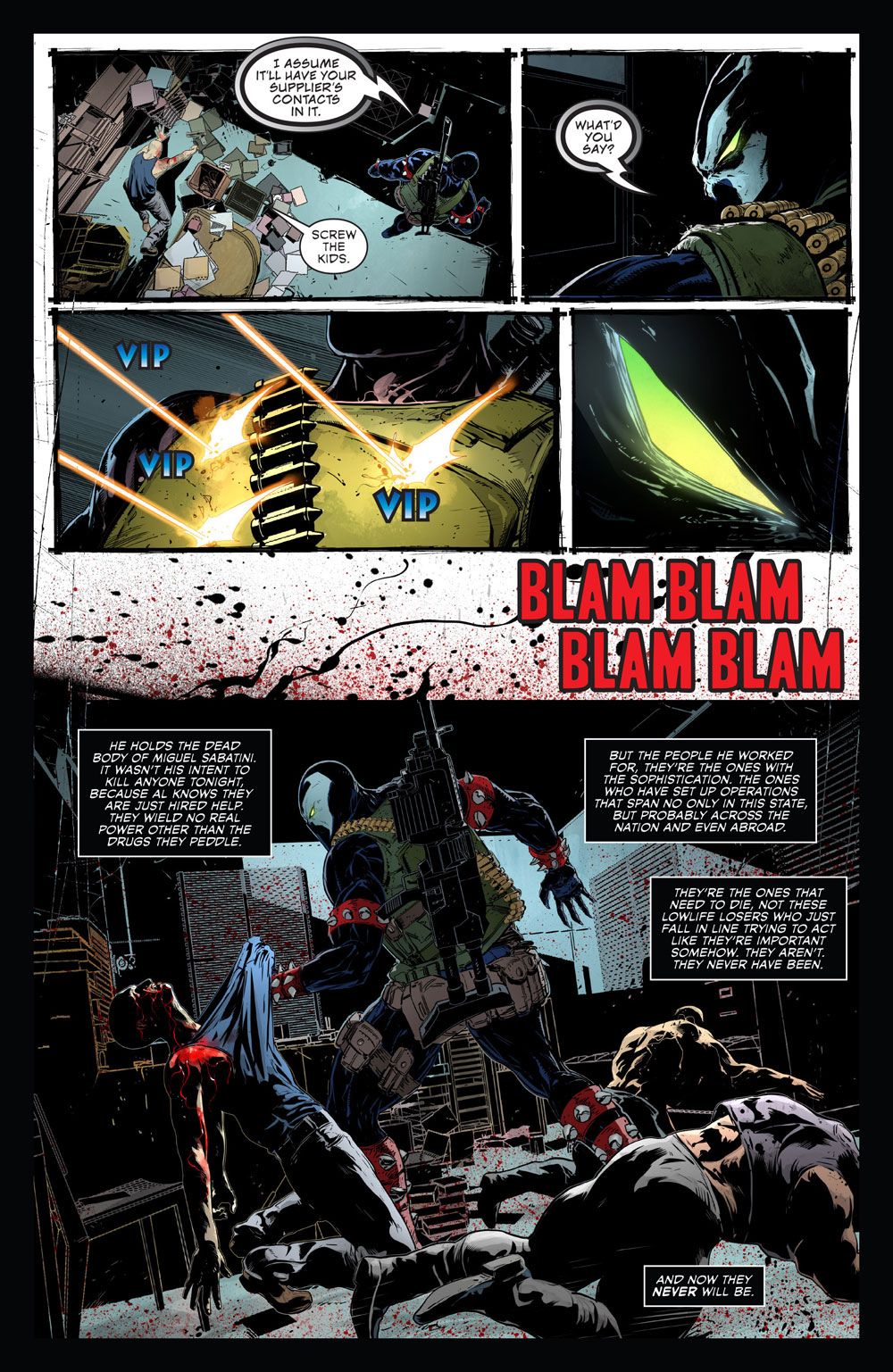

Following the rather murky circumstances of Al Simmons' resurrection during the Jenkins/Jonboy issues, the title character no longer has a face of raw meat. The previous year did little with the physical alteration of the book's hero, but the Larsen issues see Al Simmons going back into the world and interacting with real people. He has an apartment, he meets some friends at a gym, and while in the process of building something that resembles a real life, tries to live up to the promise he made his wife. It's the set-up you might expect to see in a 1970s Marvel Comic, which isn't that much of a surprise. Erik Larsen has spent much of his career creating an homage to the '70s comics of his youth.

The more traditional status quo sees Spawn facing random evil as it appears. There's no expectation that these evil forces must have a connection to the afterlife; they just have to be baddies with quirky designs. "Spawn" has never seen a run of issues that are less about brooding and more about extended action sequences. After years of "Spawn" going in the direction of classic "Hellblazer," the Larsen issues brush the goth aside for more of the manic energy seen in "Savage Dragon."

And this didn't last, either. On Facebook, Erik Larsen announced he was leaving after his ninth issue, with Larsen explaining that his collaboration with McFarlane was a constant reminder that "Spawn" was not his book, with McFarlane doing heavy rewrites and rearranging pages, and even panels, regularly. Where does this leave the title? With Szymon Kudranski as the artist and McFarlane providing the stories and additional art. The exact creative team that brought us "Spawn" #250, and several years of the book prior. After over two years of attempts to bring publicity back to "Spawn" and introduce new blood, the title would seem to be back in the same spot.

McFarlane has likely learned some lessons in recent years, however. He hasn't dropped the new status quo, and seems committed to focusing the book on Spawn/Al Simmons' interactions with the world around him. Kudranski has taken a bold turn, moving away from the restrained, realistic style of his earlier run and attempting to evoke the cartoon element of McFarlane's earliest issues. McFarlane is providing the inks, blending his style with Kudranski's and getting back in touch with the peculiar combination of light and dark elements that attracted so many fans years ago.

Will this be enough to maintain interest in the title? Can McFarlane resist his instincts and keep Spawn out of that alley? How long before "Spawn" is ready for the next high-profile creative team? Keeping an independent title alive is not easy, especially in a competitive marketplace, but McFarlane seems determined to prevent "Spawn" from slipping back into obscurity. Not only has he revived the once wildly successful "Spawn" toyline, but he's also connecting with fans through his live Facebook drawing sessions. Thought you'd never see McFarlane draw Wolverine or Venom again? He's doing it there, and showing off just how tight his skills remain. McFarlane can burn through an image in what feels like seconds, with virtually no under-drawing, producing impressive headshots of various characters on his tablet. This might seem like a small gesture, but it reminds people that McFarlane’s still out there, still producing one of the longest-running independent comics ever published.

McFarlane’s inspiration, Dave Sim, concluded his run on "Cerebus" after 300 issues, a mark "Spawn" will soon be reaching. Admittedly, Sim’s use of outside help consisted of a background artist, while McFarlane has brought in entire creative teams, but "Spawn" is undoubtedly his book, for good or ill. The odds of "Spawn" ever reclaiming its spot as the industry’s top title might be slim, but its creator is dedicated to the book’s endurance. Very few independent comics have lasted for a continuous twenty-five year run, and that level of stubbornness suggests that "Spawn"'s run is far from over.