As you no doubt know by now, Matt Groening announced earlier this week that he's bringing his long-running weekly comic strip, Life in Hell to a close.

If it hadn't felt like it already, Groening's announcement certainly signals the end of an era, in this case that of the alt-weekly comic strip, a product Groening, along with Lynda Barry and Gary Panter, pioneered back in the early 1980s (OK, Feiffer was the true pioneer but let's for argument's sake let's play along with my faulty thesis). Together, they showed hungry cartoonists a way to earn, if not a living wage, at least a regular paycheck, and many people -- Keith Knight, Tom Tomorrow, Ruben Bolling -- followed in their wake as more and more urban areas developed their own version of the Village Voice and L.A. Weekly. Whether it was for financial reasons or (as I suspect) an ever shrinking readership, Groening's exit, confirms what many have long suspected: That market, thanks largely no doubt to the Internet, has disappeared.

Of course, many of you probably came to that conclusion a long time ago. In fact, I'll bet many of you who read Groening's initial announcement were under the mistaken belief that he had given up the strip years ago. I certainly couldn't tell you when the last time I read the comic was, but I suspect it's been at least a decade, maybe more.

Part of that is due to not having access to a weekly paper -- out of sight, out of mind. I wonder at times, however, whether Groening has fallen out of favor, at least a little bit. I've seen the occasional bit of criticism aimed at him -- that the strip itself is too repetitive for example (how many endless variations of Bongo being confronted by his angry, silhouetted father, or of Akbar and Jeff kibitzing over their relationship could he do?). Even where The Simpsons is regarded, Groening doesn't always get a free pass. John Ortved's book I Will Not Write an Uncensored, Unauthorized History of the Simpsons, suggests that Groening was more interested in (and adept at) licensing the characters and dealing with the merchandising than actually writing or producing the show.

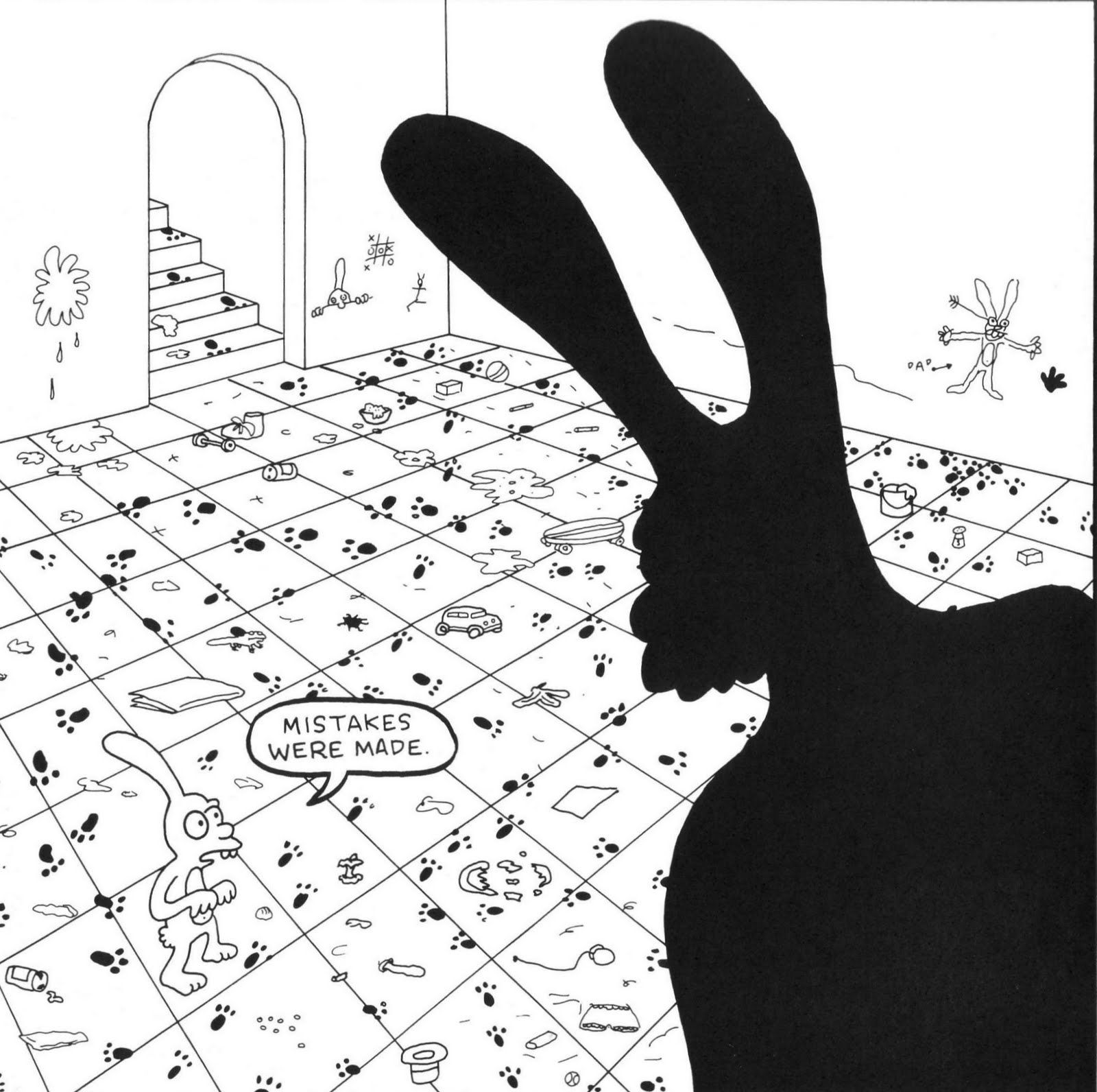

All of which strikes me as more than a little unfair and neglectful of how sharp and funny a cartoonist Groening can be. At its best, Life in Hell was one of the smartest, funniest and certainly bleakest comics going. It was certainly far darker than The Simpsons, which had producer James Brooks and company on hand to add a dash of warmth and humanity, all the better to help soften the satire. Bart might have been a troublemaker, but he had friends and family (or at least his mother) to count on. Lisa might feel lonely and ignored, but she had her intelligence and love of learning to comfort her. Poor one-eared Bongo has none of those things. Barely tolerated by his father, Binky, a failure in school and taunted by both peers and adults, he -- like just about every character in the strip -- has precious little to cling to for solace. I'm reminded of one strip in particular, which begins with Bongo praying to God for a good day. The rest of the strip details the horror that is Bongo's life -- bullies, bad grades, etc. -- only to find him once more praying to God and thanking him in advance for his "infinite wisdom and kindness." That strip goes to a place that The Simpsons never dared.

I was first introduced to Life in Hell through School is Hell, the third (I believe) book collection of Groening's strip. I was in high school at the time and was amazed at how painfully accurate Groening's comments on school life and culture were. In the pre-Simpsons-era, Groening's no-nonsense smartassery was like a breath of fresh air. Here was an adult who -- amazingly enough -- didn't forget the traumas of adolescence or goop them in some hazy nostalgia. For someone not yet ready for the in-your-face horror of Crumb or S. Clay Wilson, Groening provided just the right amount of non-conformity and questioning authority my teen-age soul craved.

It helped that he was extremely funny. To this day I prize any work of art that can make me laugh out loud, let alone bring tears to my eyes, and Groening's strip frequently did just that. I laughed myself into hysterics over his observations about, say, guidance counselors, the confusion and loneliness we endure in childhood, the perils of relationships, the agony of work and the bitterness of being an unrecognized genius. And while success might have mellowed his bite, Life in Hell continued to delight in later years, as Groening's two sons, Will and Abe, took center stage to offer their thoughts on monsters, vampires and all sorts of other supernatural fascinations.

Groening will, of course, be best known for the Simpsons and Futurama, and that's perhaps how it should be. The show remains one of the cultural lodestones of American culture, up there with the Dick Van Dyke Show and The Sopranos (even if now it's barely a shadow of its former, brilliant self). But for me, Life in Hell, at its best, presents Groening at his most free-spirited, angry and inspired. I don't know what he'll do from here on out, but at some point I hope it involved drawing goddamned rabbits.