Sure, everyone gets worked up about turning comics into movies, but what about the other way around? Cartoonists have been attempting to cram great works of literature or art into tiny panels since the birth of Classics Illustrated. But many of these adaptations, despite the noblest of intentions, fall horribly flat or fail to evoke a tenth of the original work's greatness.

There are exceptions of course; comics that not only manage to capture or add to the spirit of the original work, but in a few cases are the equal or better of the source material. Here then are six such examples. Feel free to include your own nominations in the comments section.

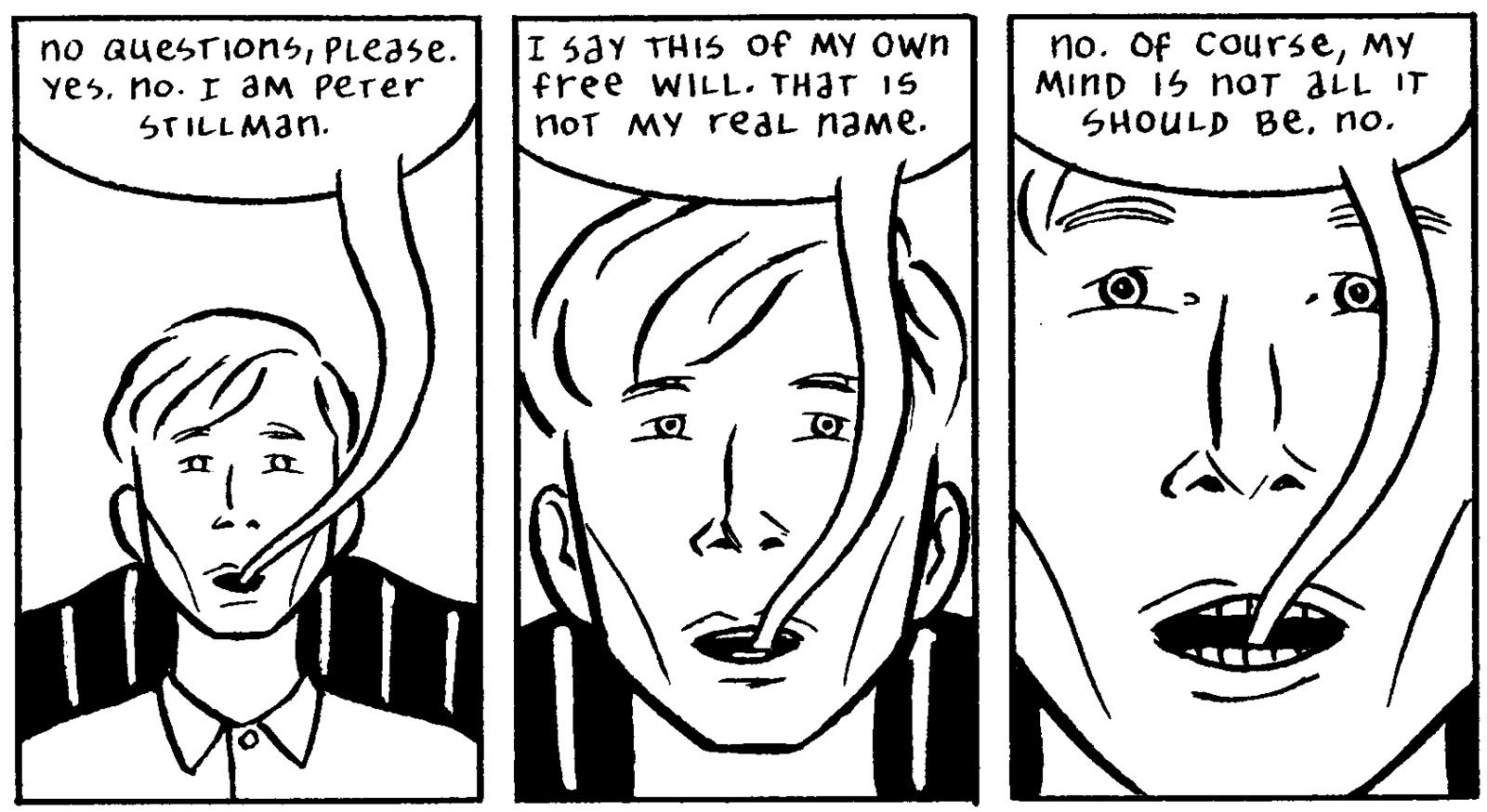

1. City of Glass. Well duh. David Mazzucchelli and Paul Karasik's masterful adaptation of Paul Auster's novel was one of the great comics of the 1990s, and it – along with Rubber Blanket – established Mazzucchelli as a daring, innovate creator capable of producing work miles ahead of the material he had done for DC and Marvel (which wasn't too shabby either). It remains a stunning, seductive, work; a knotty, elliptical mystery novel about identity and the nature and purpose of language and fiction that refuses to provide easy, pat answers or conclusions. And rather than simply illustrate Auster's novel, Karasik and Mazzucchelli add to it, creating indelible images that add depth and meaning to Auster's words, particularly during Peter Stillman's famous monologue sequence. Thus, some argue that the comic surpasses Auster's original in quality. I don't know that I would be able to dissuade those people from such a presumption.

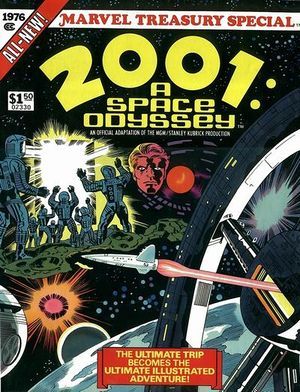

2. 2001 by Jack Kirby. It's hard to think of two artist further apart in style and tone than Jack Kirby and Stanley Kubrick (well, OK, it's not THAT hard). And yet Arthur C. Clarke's tale of man reaching the stars and evolving into a higher life form seems tailor-made for Kirby's interest and talents. Melding the finished film with Clarke's book and an early draft of the screenplay, Kirby gives the story his all, creating stunning, vast interplanetary scenes and creating dynamic, highly charged layouts. Although it's much more literal and expository than Kubrick's version, and it stumbles in trying to convey certain plot points that were easily delineated in the film, it's still a fascinating, compelling work and deserves re-evaluation.

3. Outland by Jim Steranko. The 1981 film Outland, directed by Peter Hymas, is a respectable but largely run-of-the-mill science-fiction film that can basically be summed up as "High Noon in outer space". In the hands of Jim Steranko, however, the story becomes something much more exciting and grander. Originally serialized in Heavy Metal, and strongly influenced by Kirby, Steranko fills his pages with challenging, dynamic layouts, creating huge, double-page spreads that feature corridors that seem to stretch on for miles or complex montages that sometimes sacrifice easy, panel-by-panel readability for the sake of a composition and sense of grandeur that can take your breath away. It's a great example of how a gifted artist can make the most mundane material seem vibrant. (FYI, check out this lengthy conversation about both 2001 and Outland.)

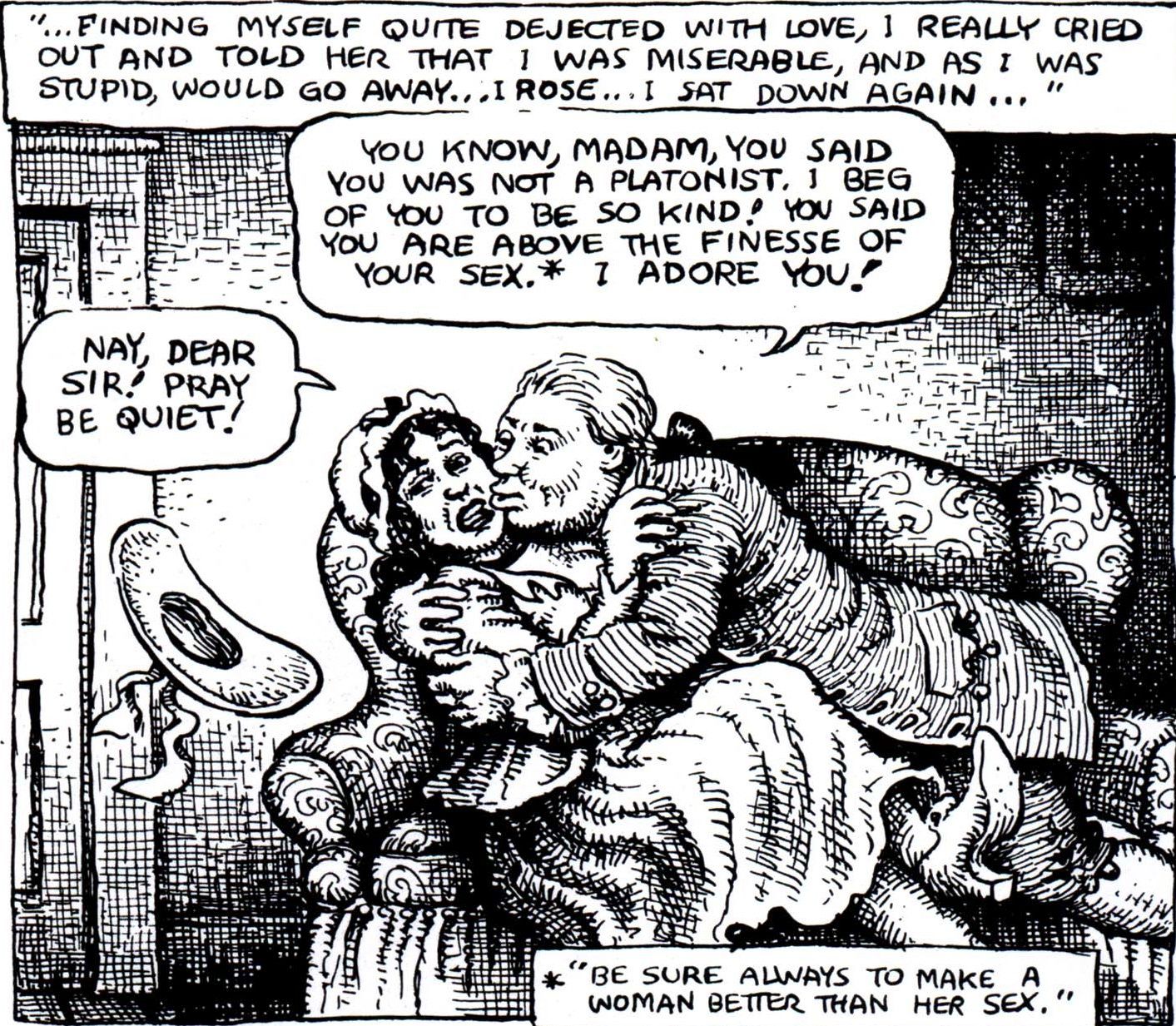

4. Boswell's London Journal by Robert Crumb. Crumb spent a good part of the '80s trying his his hand at different formats – biography, nonfiction, autobiography, etc. – in the anthology Weirdo, including adapting a number of prose works. My favorite of those is probably his five-page excerpt from Samuel Boswell's London Journal. Crumb makes the implicit deliciously explicit, drawing Johnson cavorting with prostitutes and attempting to get in the dresses of a number of pliable women in between discussing philosophy and literature with learned men or feeling sorry for himself. If that doesn't sound like the ur-Crumb comic, I don't know what does.

5. Green Tea by Kevin Huizenga. The premise behind Sparkplug Comics' 2002 anthology Orchid was simple: Get a handful of alt-cartoonists to adapt some classic and not so classic Victorian ghost/horror stories. Huizenga's pick, concerning a man who has frightening visions of a murderous monkey that seems to spur him onto commit horrible crimes (or at least suicide), would be noteworthy enough on if the cartoonist had been content to keep within the boundaries of the story. But Huizenga ups the ante considerably by having the tale bookended by his modern-day everyman Glenn Ganges, who relates a similar story involving the harrowing vision of a dog with ... something ... in its mouth. This simple addition lifts the story from mere adaptation into something original and inspired and remains one of the author's best works to date.

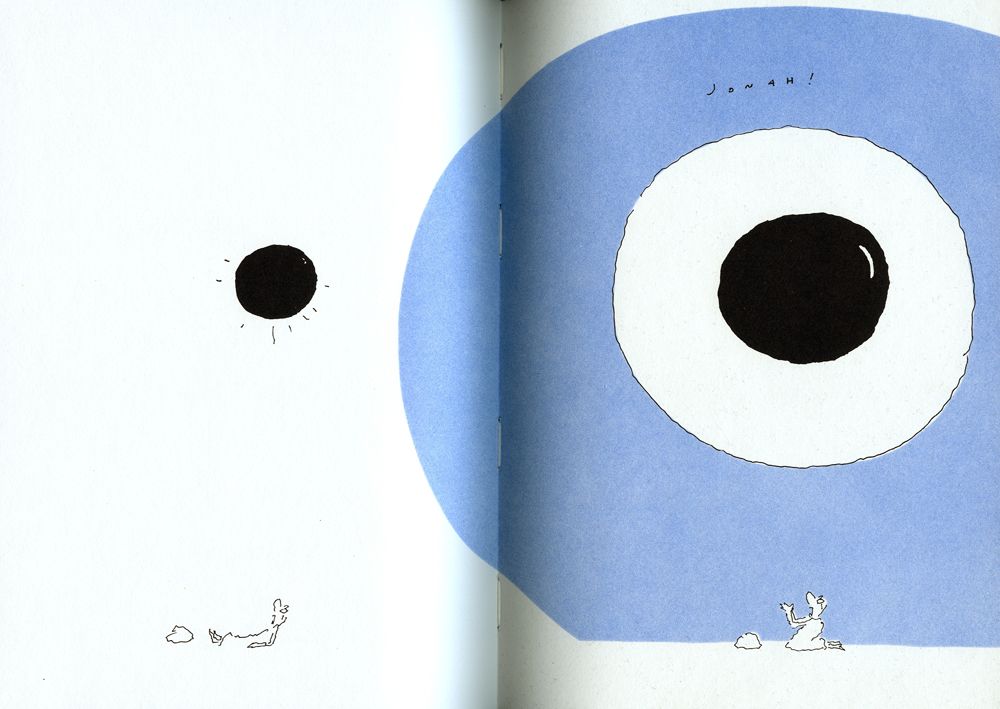

6. The Book of Jonah by R.O. Blechman. Crumb's not the only cartoonist that's attempted to adapt books from the Bible. In 1997, Blechman retold the story of Jonah and the whale, using his usual sardonic, urban tone. The end result is the story of a man desperately attempting to avoid his fate (in this case God's order to turn the city of Ninevah away from their wicked ways) and being thwarted at every turn. The book ends with the nebbishy Jonah failing at his task and bearing witness to God's terrible wrath and then – just when everything seems to be over – he has to suffer through the whole thing again. Combining both spiritualism and dark cynicism with large dollops of humor would seem to result in a schizophrenic book, but Blechman manages to walk the narrow tightrope he's created rather well, resulting in an oddly touching book.