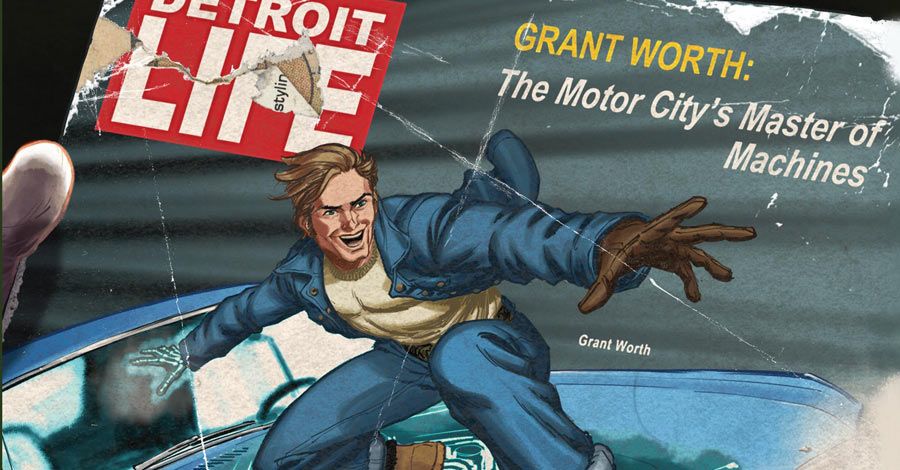

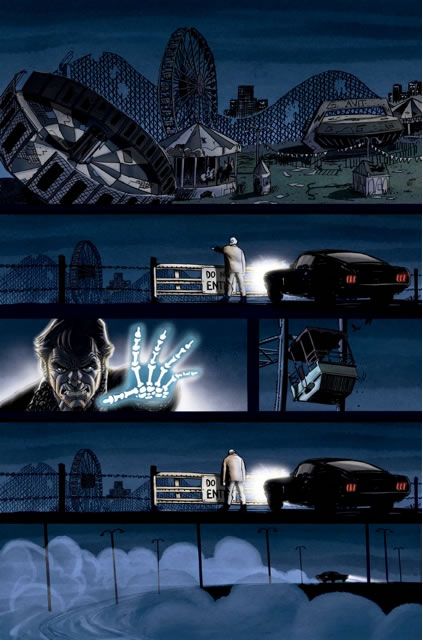

When you're seemingly worthless, can you still be a hero? This is the underlying question that runs through writer Aubrey Sitterson and artist Chris Moreno's comic, "Worth." Opening in Motor City itself, in the '60s, the eponymous protagonist is a protopunk badass who has the ability to talk to machines. The world is his engine, baby, and he knows just how it works.

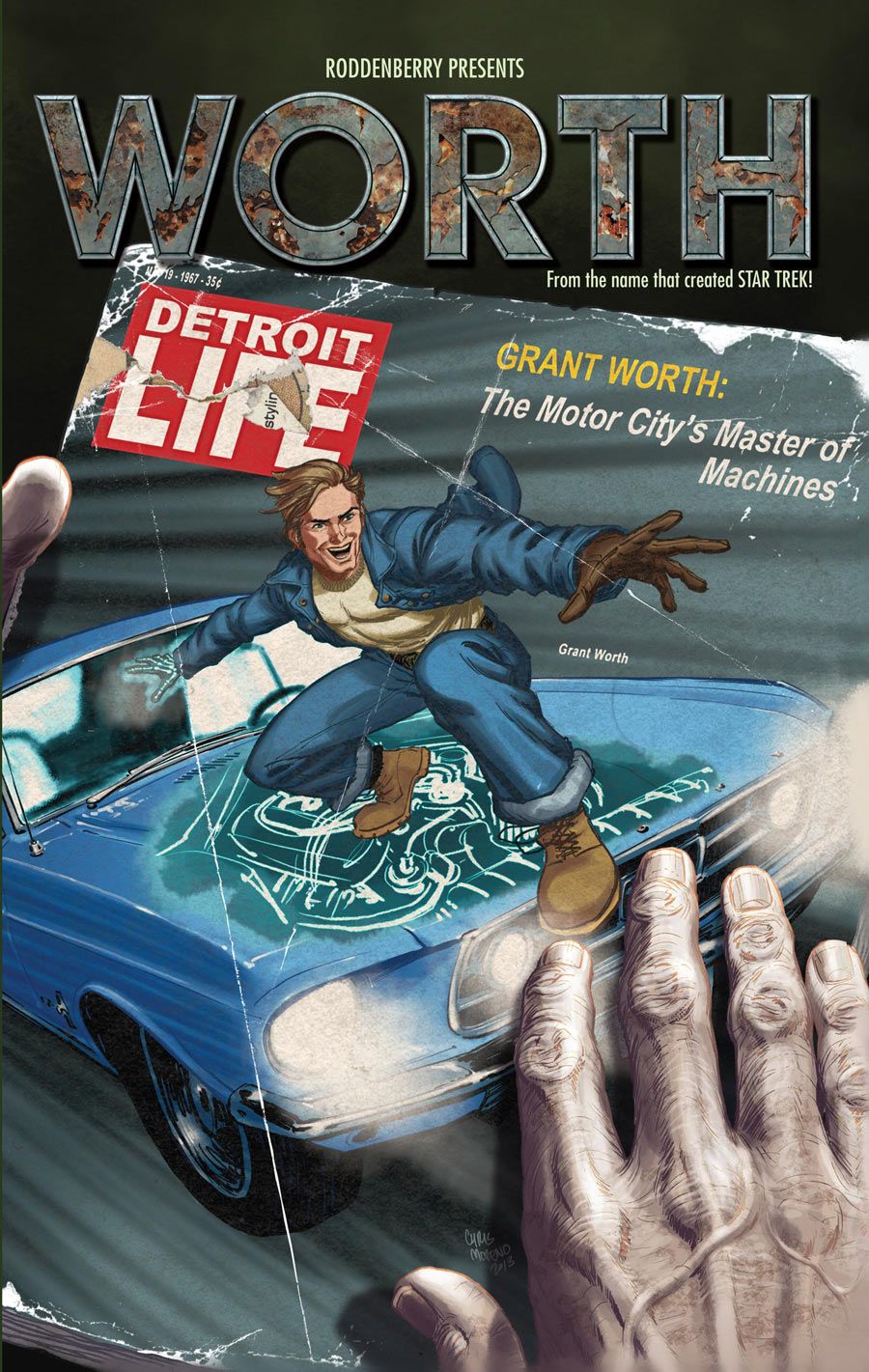

But things change, society advances, and someone who can talk to machines may one day find they're no longer greasing the bearings like they used to. Fast-forward to the future, where technology has evolved in tremendous ways, and the young man who could talk to machines is now an old-timer who can't quite cope with the binary world. The entire story is available digitally, and has arrived in print this week via Arcana and Rodenberry Entertainment. Both writer and artist spoke with CBR about their work process, tinkering with machines and the worth of their comic.

CBR News: Aubrey, tell me about "Worth." What's it got that other books don't?

Aubrey Sitterson: A swinging late-'60s Motor City protopunk protagonist -- and that's just in the first six pages!

Seriously though, "Worth" is a really interesting project for me because it's about a superhero, but is far, far, far from being a typical superhero comic. While it definitely has its fair share of wham-bang action, my goal in writing "Worth" was to create something with a greater thematic weight -- something you could really ruminate on.

The main way I went about that was to utilize something that all of my favorite comics have in common, but far too few books on the stand actually utilize: Subtlety. With actions truncated down to individual panels, and any dialogue taking up page real estate, it can be extremely difficult to layer subtlety into comics.

That's why I went into "Worth" with a set of themes and concepts I was excited to explore, so that making sure they're poked, prodded and held up to the light on every page of every scene, was actually super fun.

What world does Worth come from, and what world does Elliot come from? How do you think that juxtaposition affects the story?

Sitterson: The thing about Worth and Elliot is that they come from the same world -- just separated by a few decades. Seemingly, everything about these two guys are different: Worth is an old middle class white guy, while Elliot is the young black son of a single parent working two jobs.

But at the end of the day, they both have the same problem: An inability to communicate with the world around them, despite, and maybe because of, their incredible talents.

While the juxtaposition of their characters and backgrounds makes for a good in to the drama of "Worth," for me, it's their similarities that are most interesting.

So why the fascination with mechanics?Do you see a correlation between man's current relationship with technology and the story you've presented?

Sitterson: Trevor Roth and the other fine folks at Roddenberry came to me with the idea of a guy who can control, and in a manner, actually speak with machines -- I thought it was an interesting concept, and one that actually hadn't yet been done to death (a rarity these days).

Once I started fleshing out the story and learning the character of Worth, however, I started to stumble across all of the fascinating thematic depth that I mentioned earlier. At its heart, "Worth" is a story about communication and the struggles that come with it, which I think is very apropos in this day and age, but it also deals heavily with the rapidly evolving state of man's position in his environment, which is why I chose Detroit -- a city ravaged by those very changes -- as the book's setting.

I think most people find themselves every now and again getting wistful for some romanticized notion of the past, whether it's because something as simple as constant intrusions from a smartphone, or as major and catastrophic as the collapse of the Detroit auto industry. "Worth" is all about coming to grips with those changes, and learning to not just survive, but thrive because of them.

Chris, how did you get involved in the story?

Chris Moreno: Paul Morrissey was my editor on "Toy Story" at BOOM!, and we had a great time working together. The opportunity presented itself that Roddenberry was looking for an artist for "Worth," and Paul dropped me a line. I met with the Roddenberry team, and after reading the treatment, I was sold.

When designing the characters and the mechs, where did you draw your inspiration from?

Moreno: I think Aubrey and I had some ideas where the characters would go, but it was a process of combining that with Roddenberry's input into the perfect mix. For Worth, I was coming from a Clint Eastwood-Peter Fonda-kind of place, and some of that went into it, but there were influences flying in from all over. I think for Elliot, I was looking at artists like Tyler the Creator, just to get away from the generic African-American character that seems to pop up in media. Elliot's a very specific character, and his interests and personality sort of defy stereotyping. Pretty much all of the characters do. So it was important to me that I try and be more specific in their design.

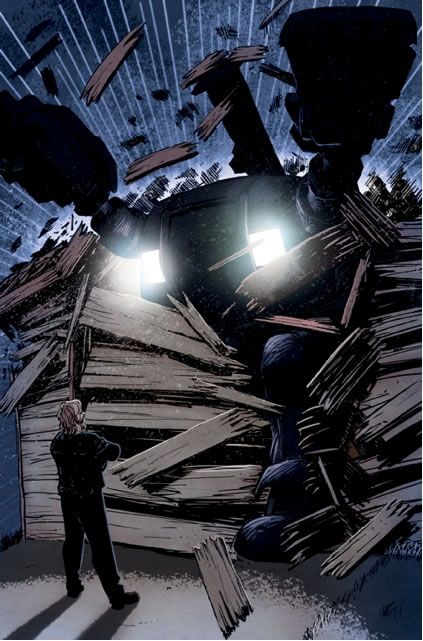

The mech was a real collaboration between everyone involved. Of course the overall note is "make it something we've never seen before!" No pressure! But I was pulling from industrial shapes, heavy metal forms, construction vehicles, and the like. The idea was that it's very much a kit-bashed mechanical creature, so it didn't have to be pretty, it just had to get the job done. Very utilitarian.

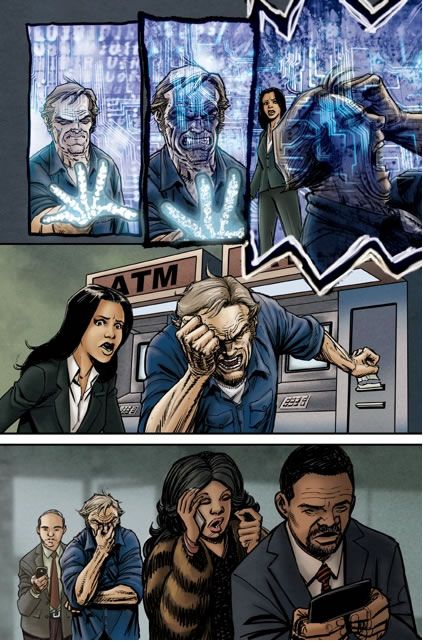

How do you go about laying out a page, whether it's simply a bunch of "talking heads" or, conversely, an action sequence?

Moreno: "Talking heads" scenes can be death, but I try to map out a trajectory to the characters in the conversation, and I try to drive their movement there to help accentuate the temperature of the scene as it builds with the dialogue. An argument between two characters, for example, is probably going to end with one character leaving, so I try to give that character a path to move through the scene to eventually exit. I think it's important in comics to always have the characters "moving", which is weird to think about because motion is one thing comics doesn't really do.

Action scenes are similar for me. Mindless action that doesn't go anywhere can get dull, but if you can figure out what each character wants and where they need to go it makes every scene have more impact. And you can also start drawing lines back to the story's themes, or create some key motifs that you can repeat throughout the story to create added meaning.

What was the collaboration like between the two of you?

Sitterson: Chris Moreno is an amazing talent, plain and simple, and the fact that he's not lavished with industry-wide praise on a daily basis should be seen as nothing less than a grotesque failure of the comics community.

Chris can draw action as well as anybody, but it's his amazing character acting that most bowled me over in "Worth. Instead of just drawing what was described, Chris made a conscious effort to understand each and every character, and all my highfaluting college boy themes. That led to a depth and, again, subtlety that just isn't seen in many other artists' work.

In addition, Chris was always on the lookout for ways to make the book stronger, and better, with countless small tweaks to what the script originally asked for that not only made the book immeasurably stronger, but turned "Worth" into a true collaboration.

My favorite bit of Moreno brand genius is probably the amazing technique he landed on for depicting Worth using his powers. I kick myself daily that I can't take credit for it.

Moreno: I hadn't worked with Aubrey before "Worth," but I was familiar with his name from his work editing over at Marvel. We really hit it off working on "Worth," pooling our influences, and really delighting in telling this story with all of our combined gusto. Aubrey really has a great command over storytelling -- everything he does in his writing serves the story and the characters. There was really no wasted space in this book. It's 100% storytelling. What really amazed me about Aubrey's writing was how he handled the small scenes, the quiet scenes. He totally helped me pull a lot of emotion into those and make them more than just spaces between action set pieces.