There's been a lot of talk about the appropriateness of violence and sexual violence in comics. It's a good discussion to have, particularly for creators who take their art seriously.

I saw a quote from the Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat in The Guardian that seemed apt, although the context of what he was talking about was different: "If there is no mission or message to my work I might as well be a [house] painter and decorator."

At some point, creators have to decide what their work is about in a larger sense -- what's their mission statement, if you will. In defining that, everything they produce serves that goal on some level. It's probably not apparent to anyone other than the creator, and some probably do it on a subconscious level, but it gives their work a unified essence that makes it undeniably them.

Or maybe that's just me, and I'm projecting that onto everyone else.

Even so, creators have to live with their work; it represents them. And everyone is going to have different comfort levels regarding what they want to represent them and their ideas, just as those that experience the work will have different levels of comfort. For some, it's run-of the-mill to use sexual violence as shorthand to establish a one-dimensional villain; it's a go-to device

For others, it's cheap, exploitative and unnecessarily triggering. It doesn't make any kind of statement about sexual violence or take into consideration the effects of such an experience on the victims.

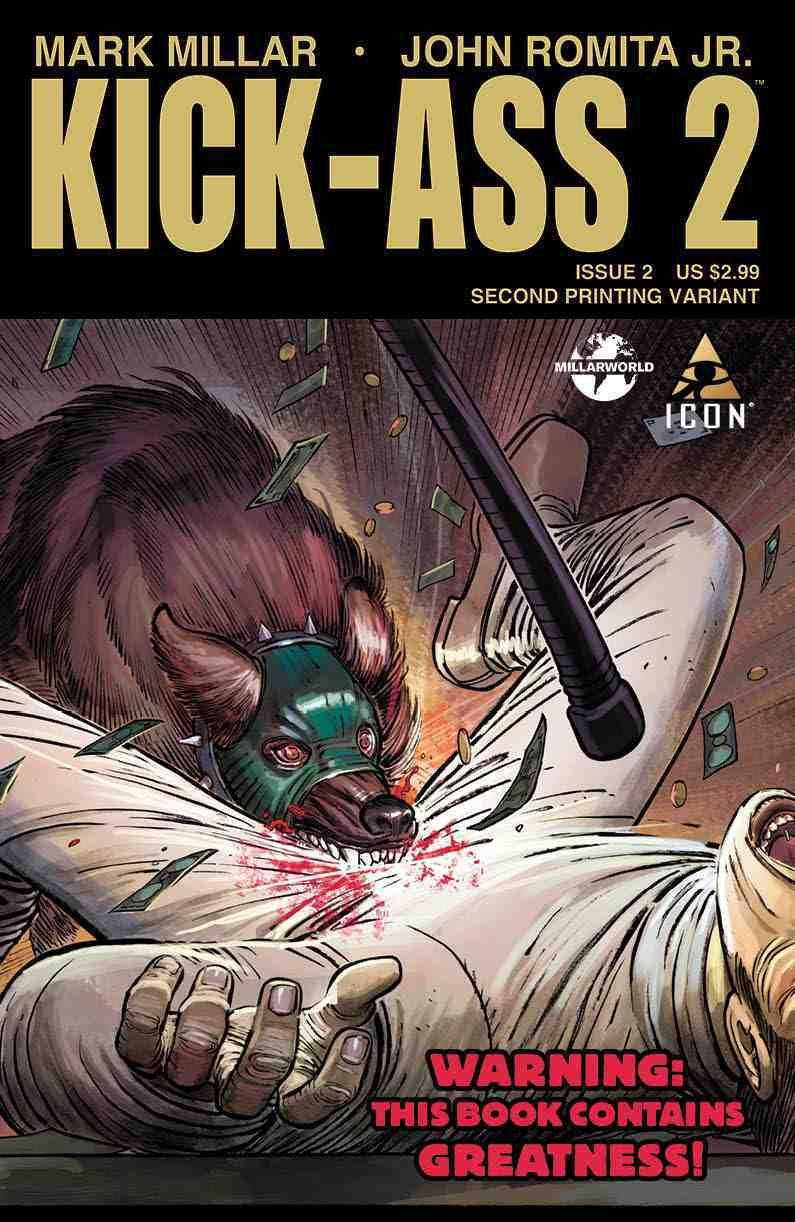

While I'm framing this as a generic example, it's of course a scene from Kick-Ass 2 by Mark Millar and John Romita Jr. that's recently come under some scrutiny. As I mentioned, it's not a unique scene, but Millar's seemingly tone-deaf comment defending his creative choice has stirred some overdue conversation. He told The New Republic, "I don't really think it matters. It's the same as, like, a decapitation. It's just a horrible act to show that somebody's a bad guy.” While both the quote and the scene are incredibly disappointing, I can't say the depiction is a significant departure from his work. To my knowledge, Millar has never shared any kind of mission statement for his work. However, another quote from that same profile suggests he has one, even if it wasn't consciously formed. In explaining the appeal of the first comics he ever read, he admits, “There's part of me that wants that outrageousness.” His comics are nothing if not a constant barrage of attempts, some successful, some less so, at being outrageous. So, sure, you could have a villain mug someone or rob a bank. Or you could end a scene with a villain saying something outrageous like, "You're done banging superheroes, baby ... It's time to see what evil dick tastes like." And be sure to include a shot of the villain unzipping his pants.

It's outrageous, it's extreme, it's meant to provoke. Or it's insulting, offensive and insensitive. But I guess that's provoking, so it's still mission accomplished.

Don't get me wrong: Being outrageous is a completely acceptable goal as a creative person; there's a long tradition in that arena. I don't consider it particularly lofty or ambitious, but we all have our own yardsticks.

Romita's response to this topic probably won't help matters: In a somewhat-rambling answer in an interview with The Beat, the veteran artist said, "There was an intimation of what could happen and what happened but you never saw a rape scene. It was foul language and it was violence to a lady, she gets hit. But there was no rape scene." He later points out that while he acknowledged it made him uncomfortable, saying, "there’s nothing that we did that was so outrageous," although maybe at that point he's talking about a different scene; it's not the most concise response. He also says that it's no worse than what is depicted in TV, movies and elsewhere. That may be true, but does he want to be part of that culture?

Romita admits it made him uncomfortable, but not enough to not do it. Writer Brandon Seifert is choosing differently for himself, saying that those types of scenes makes him uncomfortable, too, and so he's choosing not to include them in his work.

To be clear, this is a personal choice for every creator -- there's no hard and fast rule here. They just have to live with themselves. I can't help but respect someone like Seifert who takes that position. However, others won't understand the big deal.

And some readers will be buying every torture variant cover for Crossed, no matter how disturbing. Hey, there are comics for everyone. I can appreciate the twisted creativity and black-comedy ridiculousness of it, although I don't know if there's any redeeming quality to the works. Part of me feels that after a while, whatever meager point about the excesses of human savagery (or whatever we can come up with) was made about three covers ago, if not two miniseries ago.

A level of redeeming quality is probably the key element to me. Warren Ellis wrote about this, talking about how it can help us to understand the deviant behaviors in our culture. Although he was talking strictly about the use of violence in stories, in the end I don't think you can address one without the other. I'm fine with the depiction of sex, violence and sexual violence in comics and elsewhere, but I want it to actually get me to think about it in a different way, beyond just the train-wreck fascination of seeing an unthinkable or unspeakable act. Whether it's rape, or whatever you would call the acts that happen in Crossed, merely being outrageous isn't enough.

The tricky part is that everyone will have a different gauge on what qualifies as a redeeming quality. It may not always be as clear cut as the "I'll know it when I see it," and that's why we have to keep talking about it. The more we understand how people respond to sexual violence in comics and other forms of entertainment, the more the creators of those stories can understand the messages they're sending. Then they have to choose whether that's part of what they want their work to be.