The Switch to Digital panel at Comic-Con International in San Diego presented a discussion regarding the emerging digital comics market, touching on topics including increased exposure of comics to readers, methods of monetization and the learning curve creators face in creating stories on a digital canvas. The panelists were moderator Mark Waid, comics writer and co-founder of digital comics publisher Thrillbent; "Bone" creator Jeff Smith; "Wolff & Byrd" co-creator Batton Lash; writer Paul Tobin; artist Colleen Coover; and comic strip "Tina's Groove" creator Rina Piccolo. The panel was an unstructured and largely informal dialogue between the various creators, highlighted by the panelists' sometimes-disparate opinions on what kind of elements constitute a digital comic book and whether these specific elements are indicative of what's to come for the medium. The dialogue itself was indicative of the relative infancy of the digital comics era.

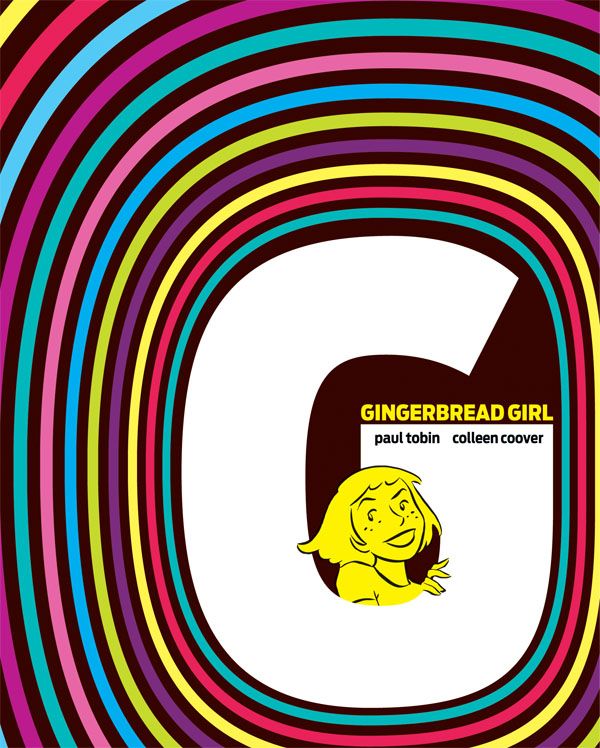

"The beauty of digital is it's very easy to spread your work, and for people to share, but the downside of that is that it's difficult to monetize," Waid opened, addressing the panelists. Regarding the idea of potential financial profit, Waid asked Tobin and Coover about their recent digital-first "Gingerbread Girl" effort for Top Shelf Productions, and that publisher's decision to make it free to readers. "Top Shelf came up with the idea," Coover responded, "and we were hesitant about it for about ten seconds."

Tobin added, "You're not really losing anything; basically it acts as systematic advertising," in reference to the eventual printed collection. "The people you lose (as buyers) are countered by the audience being able to grow."

Lash cited how the direct market stymied sales and the audience growth of "Wolff & Byrd." "I had a book that was getting very positive feedback, and at conventions I'd do well, but the direct market wouldn't carry it, because it was black & white. You just can't keep publishing something that doesn't have money coming in." Lash went on to explain that how when he started publishing digitally in 2005, readership not only went up, but sales of his existing trade paperbacks increased. Smith was more tentative regarding the potential benefit, referencing the free digital serialization of his new title "Tuki," but stating that he had no way to gauge how this release would impact the print version of the comic, positively or negatively. Lash also mentioned his new digital comic "Zombie Wife," which is also published digitally and then collected in trade paperback, leading Waid to begin discussing how this impacts publishers.

"It allows you to flip the paradigm; it shifts the burden to paying only for the actual production of the material upfront," Waid observed, adding that printing costs can now come later in the publishing process. Regarding printing costs, Tobin added, "Success can be kind of damning sometimes," referring to initial underprinting of a successful comic that can stifle sales, and then subsequent overprinting that can cut into its profits. "If you have a trade paperback that's out of stock, it's really hard for readers to continue." Coover summarized the benefits of digital publishing with, "Zero inventory, infinite supply."

Waid went on to bring up the geographic challenges faced by readers who don't live in close proximity to a comic shop, and how digital release makes this a non-issue. He then went on to discuss the dilemma posed by such widespread availability of digital comics. "It's a weird knife's edge," Waid stated. "It's awesome that everyone can access your comic, but how do you conquer that signal-to-noise ratio; how do you get heard with your material?" No answers were forthcoming, but Lash made a comparison between today's emerging digital market and Top 40 radio fifty years ago. "You heard a song on the radio for free," Lash commented, "and if you liked it enough, you went to the record store (and bought it)."

"There is so little bleed between the people who just buy digital, and the people who just buy print," Waid continued, in reference to the comic reading public. "There's not much overlap there, and they're not hurting each other. We said this five years ago, and retailers came at us with torches and pitchforks, convinced that digital was going to be the doom of comics." Smith was quick to clarify, "They were convinced it was going to be the doom of comics retailers."

Addressing Waid's point that the advent of digital has not doomed comics, Tobin added, "We're redefining what comics are at this point." Waid stated, "The language of digital can be as different as you want it to be."

"When I decided to do my comic strip as a comic book, my first thought was this is just a twenty-two page comic strip, but that's not true, because a comic book has a different language from a comic strip," Lash responded. "When I started the webcomic, I thought this is just a comic book online, which [also] wasn't true."

Coover shared a different approach she took on drawing a digitally enhanced comic, noting that she drew it digitally rather than on paper, which would have been a more difficult task if she didn't have experience in both media. The additional challenge was understanding that the comic would eventually end up in a printed edition. Waid acknowledged this challenge, but stated that ultimately, artists need to take advantage of the digital format and not worry about the eventual printed edition.

The topic of the enhanced artistic capability that digital allows gave way to a discussion about one of the earliest tricks ever to be used in digital comics: limited animation, or so-called motion comics. "Motion comics is where they take the artwork and separate from the background. It's (expletive) animation," said Smith.

Waid provided the most quotable line of the panel, stating that "motion comics are the devil's tool."

"It's not comics if you're not in control of the pace of reading the story," Waid said. "Anything that introduces element of time makes it like watching a cartoon."

Tobin offered a defense of motion comics, comparing their state today to the poorer quality of comic books from the 1940s and noting that there will likely be an evolution. "I won't totally damn it," he said, to which Smith added, "I will totally damn it."