Nate Powell wowed indie readers back in 2009 with the release of Swallow Me Whole, a haunting graphic novel about a teen-age brother and sister suffering from mental illness and attempting to hold themselves and their family together.

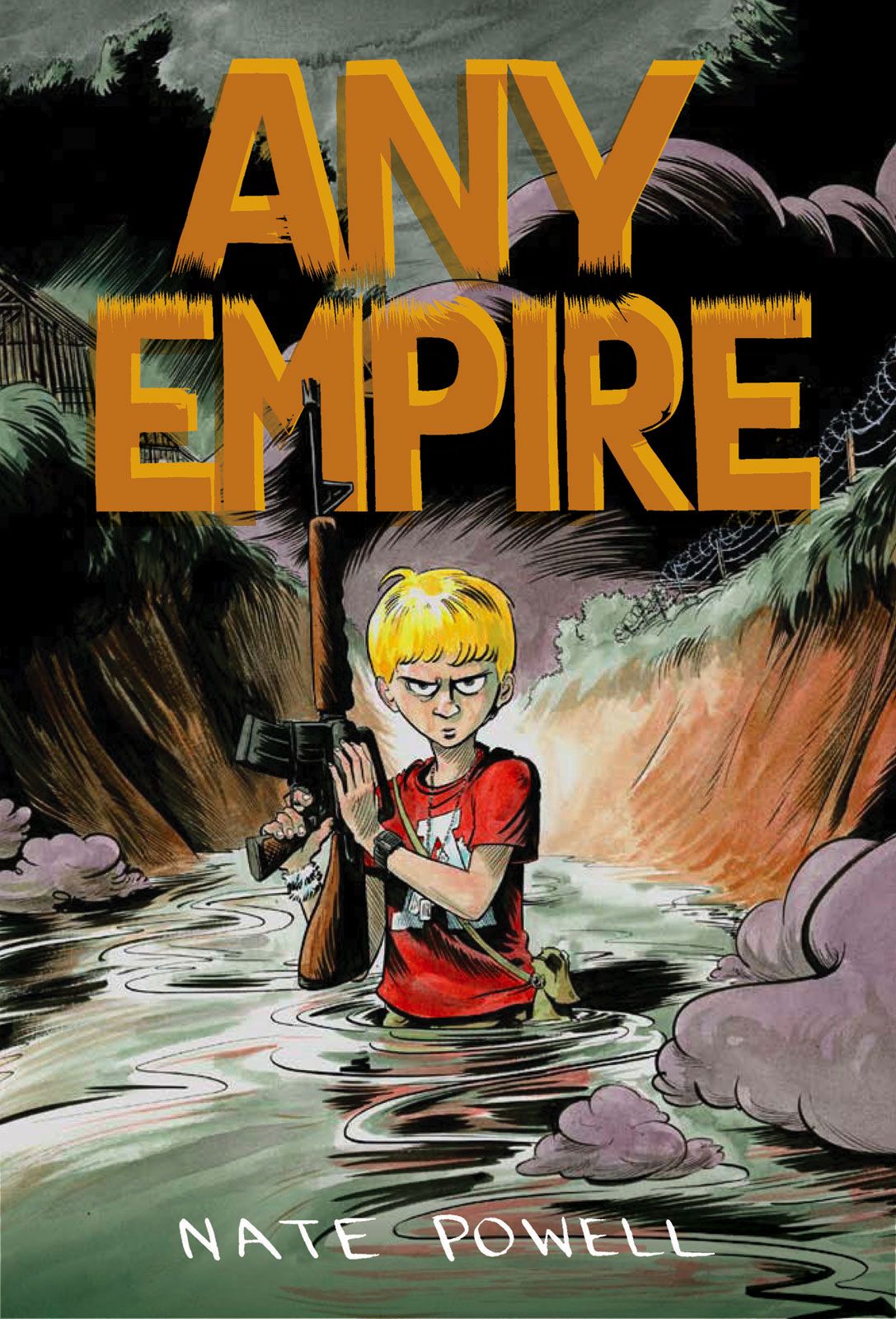

Now Powell has released his follow-up to Swallow, Any Empire. The book, available through Top Shelf, examines the way children are taught about war and violence and how even "acceptable" military violence can end up appearing on our city and town streets.

The book debuts in San Diego this week, and should be in stores next month. We talked to Powell about the book and its underlying themes, both political and social.

Let's start by talking about the book's origins. How did Any Empire first take shape?

Well, the book emerged as I was finishing up Swallow Me Whole, and I'd been pretty impacted by the books Human Smoke by Nicholson Baker, On Killing by Dave Grossman, the movie Children of Men, and also a zine supplement in an LP by some friends Please Inform The Captain This Is A Hijack. I'd been very focused on the long history of the state's prime directive of ensuring its own existence, even if that meant killing or imprisoning its own citizens, or provoking air raids to flatten its own cities for a "proper" moral justification for war (as was one of Churchill's many shadier moments leading into WWII). We've all grown up accustomed to seeing smoldering wastelands on CNN, but I began imagining the rubble as buildings, transplanting foliage back onto the blight, and couldn't stop imagining my own neighborhood as a wasteland indistinguishable from the ones I'm so used to seeing on the news.

That, coupled with the culture of fear and distrust in which we live, the explosion of populist authoritarian rhetoric and evangelical bullshit, got me started on the book. It was originally a shorter, more concrete, essay-like book whose approach was pretty influenced by Gabby Schulz/Ken Dahl's books. Over time, it became more and more about living with a very specific privileged fantasy surrounding violence, particularly state violence, and how our own perspectives on that cultural glory-myth will continue to crumble as we're forced to join the rest of the world in the next fifty years.

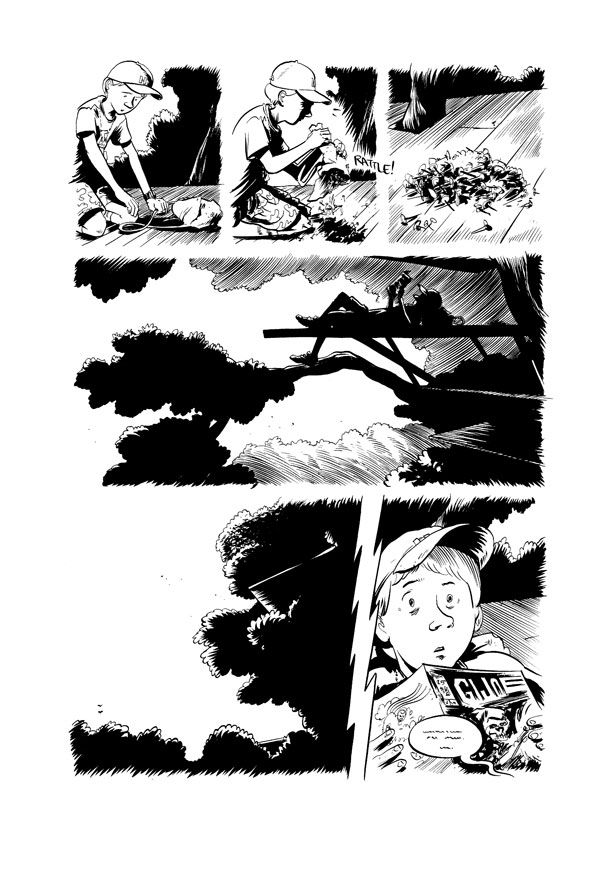

Certainly issues of fantasy violence versus real violence are explored in the book, especially with one character's daydreams/games involving his action figures. Did you draw upon personal experience for those scenes at all? Is anything in the book autobiographical and if so to what extent?

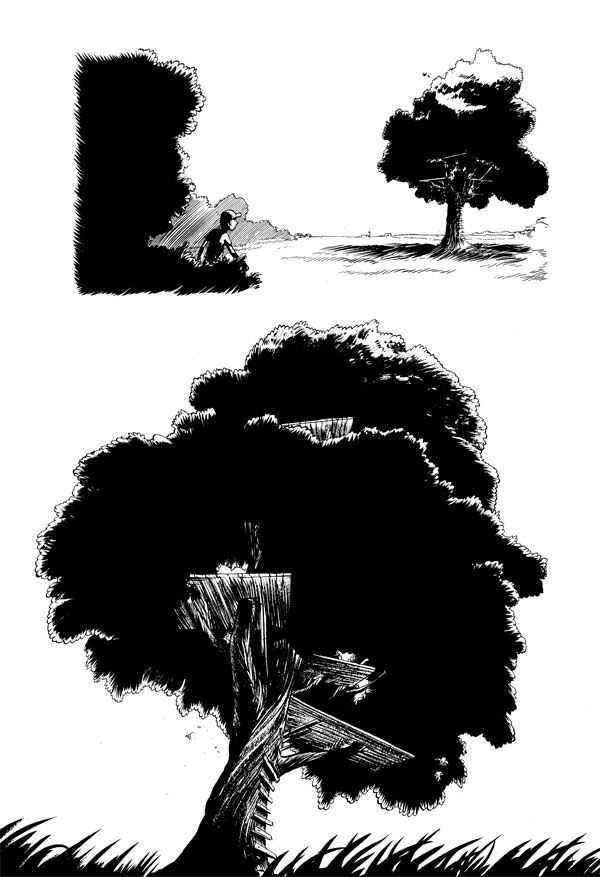

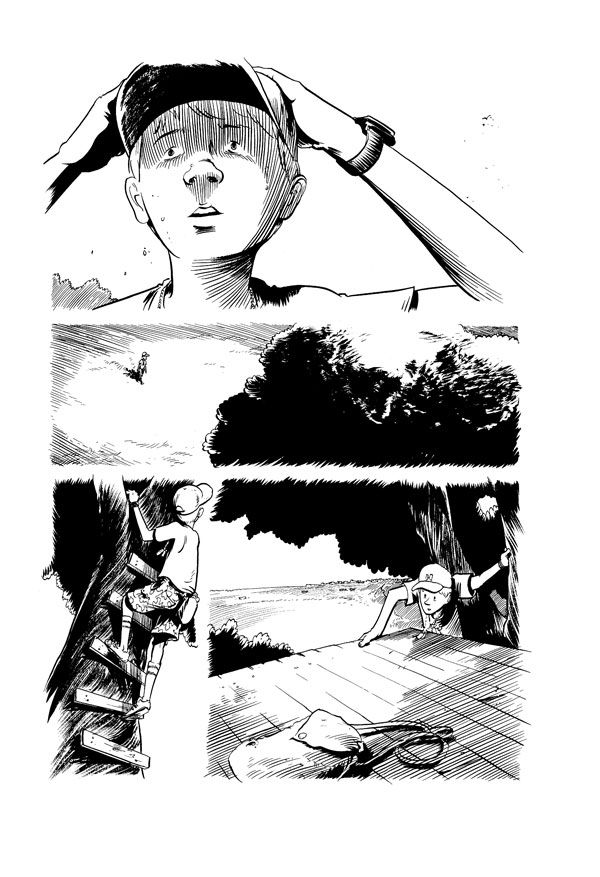

The book is a work of fiction, but yes, I was definitely a G.I.Joe kid, and I grew up in the South in a military family. It's unavoidable that Lee is essentially me as a kid, and a lot of his experiences are similar to things that were part of my life. I was (and still am) a pretty private individual, despite the fact that a lot of my life comes through on the page. As a boy, I played plenty with other kids, but it was an entirely different kind of play. Most of my imaginative play was intensely private, and the space carved out had a certain sacredness to it -- it was essentially the same space I later discovered could exist when making up worlds in comics.

Like most of my books, characters often have a basis in real people, and a lot of situations are based on something that really did happen, but the who and the what are often entirely shuffled around.

As with Swallow Me Whole, the book also deals with issues of childhood, fantasy and the tricky segue into adulthood. Are these conscious themes you like to explore?

In each of these stories, these themes presented themselves as very natural elements of the story. With the completion of this book, though, I finally feel satisfied enough to be disinterested in exploring adolescence much further in books, at least for now. Spending a few years on a single story is also weird, because by the time you finish a book, you sometimes can't wait to move past certain issues or themes that might've burned in your heart three years prior. Highly subjective experiences will always be a focus to me, but the fantastic elements in this book are largely in relation to our cultural delusions of invincibility, of exceptionalism, and of moral preeminence.

The book jumps around in time a bit, and moves from fantasy to reality and back again. Were you concerned about the reader's disorientation at all? I got the feeling at times you wanted the reader to be a little unsure if a sequence was really happening or was in the character's head.

My sequences and transition give that feeling a lot, and I think they just require taking the sequence of events at face value. There's a little bit of revisionism in one of the character's heads as an adult, and some weird Twilight Zone business that brings the present day reality back around to an earlier imagined scene, but the division between fantasy and reality is certainly more clear-cut than in Swallow Me Whole.

Generally, scenes from youth occur without panel borders, unless they're total fantasy scenes. Adult fantasy scenes sometimes have a formal affectation too, but it's honestly not very important to figure out what's really happening and what's not. The big scene that leads into the end is really happening on the streets of Wormwood, and is based on a highly questionable Marine exercise in an impoverished neighborhood of my hometown in 2002. For six weeks, the DOD performed live urban warfare training exercises as people were trying to get about their daily lives. Not a stretch of the imagination by any means-- the state just truly doesn't give a shit.

Apart from the books you initially mentioned, did you have any other specific comics or comic creators that you referenced while putting the book together? Especially as far as the look and design of the book goes?

I'd say that Dylan Horrocks' Hicksville and Anders Nilsen's Big Questions series certainly made their mark on the page layout and narrative flow. Swallow Me Whole was kinda drawn in a vacuum and was really freeform in certain ways, so it was exciting to reel the layout back in, and define a little more carefully what was signified by certain aesthetic choices. That approach revealed more patterns and themes within the book than I was initially aware of, and discovering those unexpected echoes was exciting.

I noticed that you tend to eschew panel borders in most of your comics. Why?

Speaking for myself, when I look at a panel without borders, it seems I internally expand my "view" of the scene far beyond the edge of the panels, and seem to slow down my reading of the image. Whenever I'd do a page that's just one floating panel in the middle of the page, it seemed to provide the sense of both a splash page and of the pause in the story's beat given by all the negative space. The next step was to see how an entire page of these vignette panels would read, and there are times where it feels like each panel on the page is its own splash page.

There's a bit of gender issues at play in the book as well, as the boys, especially Purdy, seem driven to be by a need to prove themselves as men and as boys engage in aggressive, "manly" games, whereas the main female character, Sarah seems, at least at first, to be the more emotional and sympathy-driven character. Are you consciously exploring these gender roles in the book and if so what are you attempting to address?

As much as the book's plot is partially driven by play, the main theme here is violence in a variety of forms. And yes, gender definitely plays a role here, but I think that we unavoidably perceive gender as more of the divide here in the story than it really is. The major differences among the characters are in what constitutes their real-life experiences with violence, how they perceive their own relationship to a formidable world, the shape fantasies take in their lives, and to what end the fantasies serve.

Lee comes from a family privileged enough to know life without domestic violence, and his father seems to've had an okay time in his military experience, so as a Reagan-era American child, he is able to purely enjoy the cultural glory-myth of bloodshed. At the same time, he is very aware of rumblings of much larger changes in his near future, and works his way through that with a series of epic, romantic, and fatalistic fantasies. As inevitable as it seems to adults, it's important to note that moving to a new house or town as a child does feel quite like a kind of violence, as privileged as that statement sounds.

Purdy is essentially always waiting for the bottom to fall out, especially in relationships with any other people. I'm pretty sure that he expects new friends and strangers to respond to his true self with disappointment and laughter, and really has no idea that there's no trick to getting people to open up to you, to sharing time together. It's all push-pull to him, one thing constantly in reaction to something else. He has essentially woven his own self-concept into a rickety fantasy of its own, so that he can present that fantasy to the world as his core self, but he's just not that weird or twisted or gung-ho at his core-- that's what makes him so uncomfortable about the twin brothers and their little cult. They seem to personify the things he projects about himself, and they see through his front.

Sarah's mom is a nurse, and I feel that she's already gained a very different exposure to violence and mortality from that relationship. Her own interest in wild animals also means that she is becoming more exposed to the brutality and chaos inherent in the wild. Real violence, the violence of hawks and field mice, beatings and heart attacks, is plenty for her, and fantasy serves a different purpose-- sleuthing mysteries are another means by which she can put pieces together and make some order out of a grim world.

Do you feel like things like GI Joe and other "boy-oriented" toys are designed to encourage boys to be aggressive and violent? Lee plays extensively with his action figures, but he doesn't take the same path Purdy does.

I mean, sure they do to an extent, but that's really a non-issue. I was neck-deep in G.I.Joe and Cold War cultural mythology, as were most boys I grew up with, and most of us turned out just fine. It's far more damaging to grow up thinking a boy should be punished or corrected for wanting to wear a dress or play with dolls, or grow up thinking that you inherently can't trust people who live in shoddier homes or who aren't white. My focus on Reagan-era toys and imaginative play was just on the ways kids always find a way to process the complicated issues in their lives, even if it's using the only vocabulary they've learned thus far, the vocabulary of power games and simple fantasies.

In reading your replies, I get the feeling this was a book borne out of anger, or at least frustration, at the state. Was making the book at all cathartic for you? Did you get any sense of satisfaction or release in making this comic (beyond the pure pleasure of making comics of course).

More than anything, I'd say that anxiety and dread were the motivating feelings. Our cultural climate has reached such levels of emotion-fueled, religion-soaked reactionary rhetoric that these extremes have worked to define themselves as a new moderation. It's disheartening for all of us to be treading water in so much mutual distrust. Amidst all these crises and transitions, as usual there is absolutely no mainstream criticism of capitalism itself, or of the dirty, dirty ways it has made room for the worst in human nature.

As people continue to grow and change, it's also so daunting to feel that people are truly expendable to those in power. A lot of effort and action sometimes feels like it can be no more than a gesture; this is the jam that Lee, Sarah, and Purdy get into towards the end. Even if nothing is fundamentally changed from our resistance, those gestures must be made. Another theme that was on my mind a lot was the legitimacy of "I don't know" as an answer. It's okay to step into the unknown, and it might be horrible, but a future full of unknowns is revealing itself to us all the time, and it's no reason to shrink away from fighting for a divergent future.

The book was certainly satisfying to work through, but more than anything I fell deeper and deeper into the connections between characters, and the unspoken conflicts tearing at them from inside. My political lean on the story tempered itself considerably while working through its multiple drafts, and I feel it only became compelling once the narrative itself overtook the pissy rants that gave birth to it. Go catharsis!