This week saw the launch of publisher PictureBox's Ten Cent Manga initiative, with Shigeru Sugiura's Last of the Mohicans introducing the line. I was a bit surprised to find that Ten Cent Manga is apparently more for highlighting books that have an interesting artistic lineage, and not necessarily older titles (in the case of Sugiura, his artwork is a bizarre cross between 50s cutesy manga and 60s American action comics). The edition of Last of the Mohicans that PictureBox published is a redrawn 1973-74 edition, whereas the original volume was drawn in 1953. I was hoping for the 1953 edition, as there are very few examples of older titles that have come out in the States. So what are some of the oldest manga that have been translated into English? Here's a look.

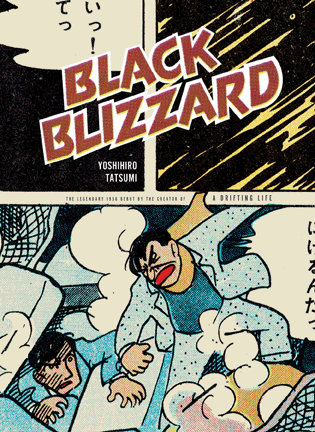

Black Blizzard - Yoshihiro Tatsumi (1 volume)

This was released in English shortly after Tatsumi's autobiographical A Drifting Life, where it is mentioned as Tatsumi's first full-length gekiga work from 1958. It is a 128-page noir story about two convicts that are fleeing a train accident through a heavy blizzard while handcuffed together. They reach a cabin, and one of the men wants to part ways by cutting off one of their hands, but the other protests, saying he is a pianist and needs both hands to make a living. The pianist goes back to tell the story of how he became a criminal, then both men flee the police again, and once more decide to cut off one of their hands to escape separately. It's a very straightforward crime story, and is well told, but doesn't get much more elaborate than what I describe. Tatsumi's early and very inky style brings a dark, chaotic look to the art, and it's interesting to see his early character designs. It reads a lot like a pulp short story, and if that's what you're looking for, it's a beautiful example. Since later gekiga tends to take a more bitter view of human nature, this one stands apart from other such works. Though a nice package (parts are reproduced in color, the page edges are tinted yellow, and the book itself is oversized), this is pretty expensive at $20, though the current "new" copies on Amazon are remainders that are selling for $8, and used copies are pretty cheap, so it's fairly easy to come by.

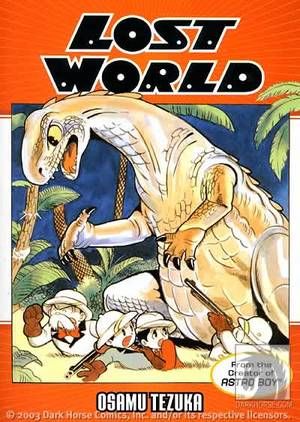

Lost World - Osamu Tezuka (1 volume)

We do have several older Tezuka works available in English, but since I could talk about him all day, I'm skipping all but the very oldest. Lost World was apparently redrawn several times. Tezuka says the oldest version dates back to 1940, but this edition is from 1948. It's difficult to summarize this book, because it has short chapters that meander from point to point. It starts with a murder in the first panel, and the murderer removes the victim's glass eye to steal a gem. The gem was being held for a child scientist named Doctor Shikishima. Detective Shunsaku Ban is investigating the murder, and runs into a criminal element that appears to be targeting Doctor Shikishima due to his involvement with a planet named Mamango, which is currently orbiting very close to the Earth. Eventually, everyone ventures to planet Mamango in a rocket ship, and finds that Mamango is inhabited by dinosaurs. The criminal element and the good guys clash on the planet, which leaves most everybody dead and Doctor Shikishima stranded with a plant lady. There's a notable two-page spread at the end of the book where Ban runs through a crowd scene made up of dozens of American and Japanese comic strip characters, including Popeye, Dagwood, Donald Duck, Norakuro, and Tank Tankuro. Lost World has a high body count, allegedly the highest in any Tezuka manga. One of the more horrific deaths features a man getting sucked into the vacuum of space, for instance. But the story was written for very young children, and it suffers from rather simplistic dialogue and a simple story that meanders in strange ways. Talking animals are a plot element at one point, and are one of many things that are mentioned, then forgotten later. I do like the 40s sci-fi aesthetic, where crowds of people get news from radios mounted in a public square, and the rather exquisite rocket ship powered by energy rocks. The art here is much more primitive than what you've come to expect of Tezuka. The Disney influences are very, very obvious, and his "cast of characters" have rough designs. The book is a little over 350 pages, and was published in Japan as 2 separate volumes. Unfortunately, the formatting isn't compatible in some spots, and sometimes a 2-page panel spread will have a large white gap running through the gutter of the book, and the art is fuzzy in places. It's an interesting (if expensive, at $18) artifact, but quite frankly, one of the worst Tezuka books published in English. It appears to be in stock and available online, but it's over ten years old at this point, so I would snap it up if you'd like to check it out.

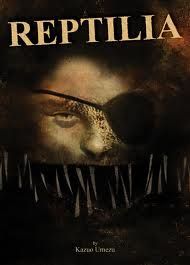

Reptilia - Kazuo Umezu (1 volume)

Kazuo Umezu is an amazing creator for many different reasons, but one of my favorite random factoids is that he is a "pioneer" in the romantic comedy genre, and a very early and prolific artist in girls' comics. Reptilia, originally published as Hebi Shoujo (Snake Girl), ran in Shoujo Friend magazine in 1965, making it one of the oldest volumes of shoujo manga published in English, behind some Tezuka. The volume is nearly 400 pages, and is comprised of three stories. In the first, a little girl accidentally frees a snake lady while visiting her mother in the hospital. The snake lady kills and takes the place of the little girl's mother, but nobody knows this except the little girl, and she's menaced appropriately by the snake lady. In the second story, the same little girl goes to visit relatives in the country, and the snake lady stows away in her luggage. The relatives dread her arrival, as the coming of the snake lady has been foretold, and they all think it's the little girl. We learn the origin of the snake lady, and she also tries to convert several people into reptiles and/or slaves. The third story, Reptilia, is a pretty classic horror story, with snake people out to turn others to their kind, vengeance, deception, orphans, a typhoon, and all sorts of horror movie havoc. Reptilia is a pretty classic kind of story, and since it's for little girls, it does read a lot like a 50s monster movie. The snake lady never does anything worse than chase after and menace the girls, and one of my favorite touches is that the girls in the book would often see something while falling asleep, like an eye staring at them through a knothole in the ceiling, get scared for a second, then fall asleep anyway, since staying up all night wouldn't be a very good message. Umezu's art is dense and claustrophobic, and one of his trademarks is his ability to draw panel after panel of children's faces frozen in terrified screams. There's a lot of that here, but it's not as well integrated into the flow of the story, so things often stop when children scream. Granted, the book is very dated, and anyone looking for a real scare would be better off elsewhere. But I love that this was published in English. Reptilia is out of print, but easy to find used copies of.

Tank Tankuro - Gajo Sakamoto (1 volume)

If I'm not mistaken, there's not another book like this in English. Tank Tankuro is a prewar children's manga, and this collection covers material from 1934-1935. The reason this is so interesting is that very few prewar manga still exist, even in Japan, so it's wonderful that we have the opportunity to see this in English. The book itself is a collector's piece. It's a slipcased hardcover with the strip reproduced in full color, and it has many essays in the back about Gajo Sakamoto, prewar manga, and the history of Tank Tankuro. The downside is that this will likely only appeal to collectors. The price tag is rather high ($40), and the strip itself is simplistic and not that interesting. The titular Tank Tankuro is possibly a robot (said to be the first appearance of a robot in manga), but to me appears to be a man with a chonmage hairstyle inside a large metal ball. Said metal ball can transform into any sort of vehicle, and it can also produce a variety of tools that suit the situation. Tank Tankuro stories usually only last a few pages, and range from mundane to bizarre and surreal. In one of my personal favorites, a big man suddenly appears inside a tree that Tank Tankuro is walking by, and his leg bursts out to kick Tank Tankuro. Tank Tankuro gets back at him by setting the tree on fire, and the last panel features Tank Tankuro eating fried eggs and roasted birds on top of the flaming tree, with the belligerent man roasting at the bottom bemoaning the fact he's been barbecued. One of the only ongoing story arcs is about Tank Tankuro going to war with an entity called Kuro-Kabuto, and the short stories are all about the battles and struggles between the two and their forces. At one point in this conflict, Tank Tankuro turns a herd of stampeding elephants into flamethrowers. I'm making this sound more interesting than it is, though. It's obviously written for children learning to read, so most of the stories have painfully simplistic dialogue in short sentences, usually to describe what's happening in the large panels. Weirdly, the dialogue is occasionally more profane than you might expect from a children's comic. The art is quite notable, as Sakamoto isn't nearly as western-influenced as future generations of mangaka, so his art has a very flat look that's easy to link back to ukiyo-e, and his character designs are far more abstract than you'd expect. It's entirely unique, and I am happy to see something like this, important as a look at a pre-Tezuka manga scene. But again, the book's value is mostly historical, as it's not very much fun to read. It should still be in print and available.