In the comments to last week's Star Trek column, someone asked a question that I thought was worth taking a full column to answer, especially since this phenomenon seems to be driving so many superhero comics today. So I'm going to answer it here now. Or try to, anyway.

It was from Edo Bosnar, and his question was, "It’s really unclear to me why such a sound and readily-adaptable story-telling engine (thanks Mr. Seavey!) like the Star Trek franchise even needs a re-boot. Am I missing something here?"

That is a really good question, when you think about it. Not so much for Star Trek -- I think we hashed that over pretty well last week -- but just generally. Why do superhero comics keep doing this? Characters that originally anchored a long-running series are getting canceled and re-started almost annually these days. Even company mainstays like Batman and Spider-Man aren't immune to this sort of thing. As for the B-listers, or the team books... good luck keeping up with those changes.

Why keep picking at your characters like that? Why not spend some of that effort getting things right the first time? Is there a reason? More to the point, is there a good reason?

Well, we'll see. But first let's define our terms.

There are people who define a superhero "reboot" and a "relaunch" and a "reimagining" and all those other press-release terms as each being different animals, but I don't really. When I'm using them here, I'm talking about simply re-starting a book in a new way. More than just a "startling new direction!" (although there are a couple of those mentioned here too) this is when your re-start means you are turning the book into something completely different.

Got that? Other people might classify it differently, but I'm going to try to stick to just the examples where the basic premise of the book or the character was changed somehow.... even if the title itself wasn't canceled, it nevertheless became a different book for all practical purposes.

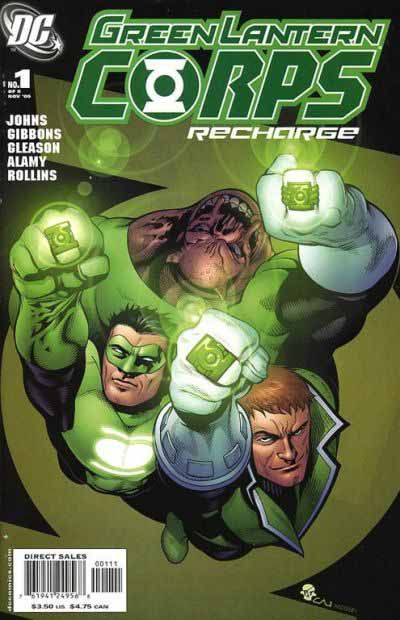

It occurred to me that there is a character out there who has, at one time or another, served as an example of almost every different kind of relaunch you can do in comics. The poster child for corporate comics desperation, for longer than I've been reading comics, is Green Lantern.

The weird thing is, Green Lantern has been a consistently successful property. The title has had several periods in the last few decades where it's been so successful it's been used as a launching pad for other new titles and crossovers and what-have-you-- currently, the book is the linchpin of this year's big Blackest Night hoo-ha at DC -- but for whatever reason, editors can't stop screwing around with it.

Edo's question seems to me to apply even more to Green Lantern than to Star Trek. Why can't anyone ever leave GL alone? Is it something inherent in the series concept itself that gives it such a short shelf life? The history of the character is such an amazing roller-coaster of big successes to low-sales cancellations and back again, one can't help but wonder.

Let's review the patient's file, so to speak, and see what we can turn up.

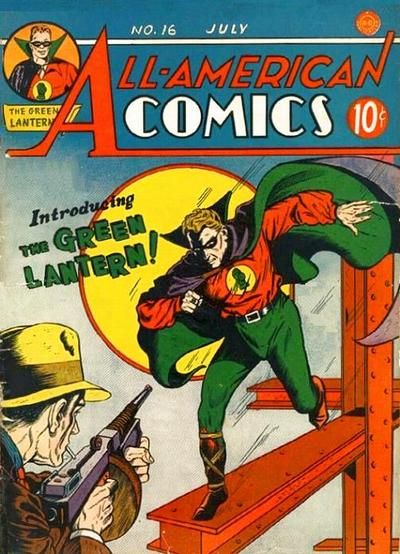

To begin with, we had the original incarnation of Green Lantern, in the 1940's.

The idea was simple -- a superhero version of Aladdin and his lamp. At first the character was even going to be called Alan Ladd, but it was changed to Alan Scott... the story goes that it was to avoid confusion with the actor Alan Ladd, but I've also heard that it was deemed too cutesy a reference to the "Aladdin" idea that creator Martin Nodell started with.

At any rate, the adventures of a costumed crimefighter with a magical wishing ring caught on and soon Alan Scott had his own magazine.

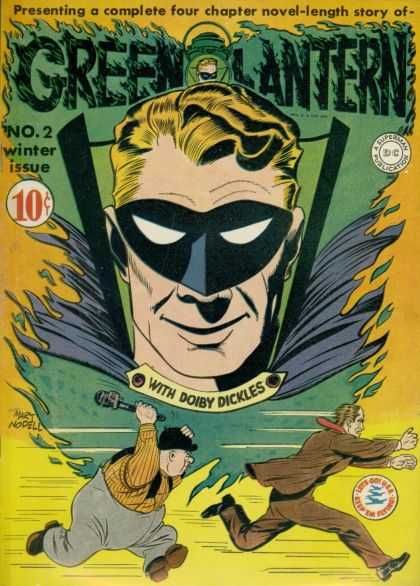

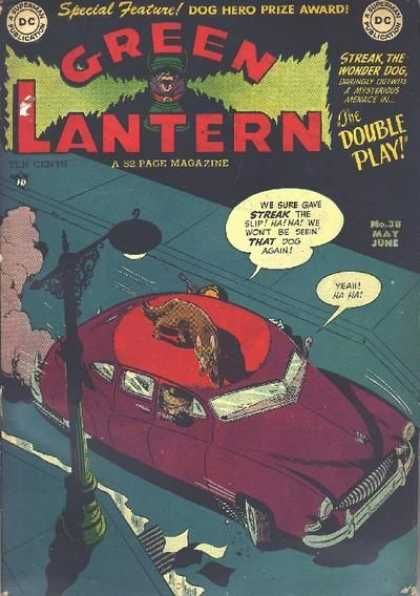

Even then, there was a certain amount of tweaking going on. Alan was given a comedic sidekick, Doiby Dickles, and eventually also Streak the Wonder Dog, who even headlined the book a couple of times.

The thing you notice when you read the Golden Age Green Lantern stories is that the ostensible hook of the whole series, the magic ring, really is played down a lot. More often than not Green Lantern just dons his costume, runs after the bad guys, and punches them in the face; you don't see Alan Scott creating a lot of the green animated ring constructs that later versions would depend on, or even using it to shoot force beams. Alan Scott usually just used his ring to fly around or to shine a light on things when it was dark, when he used it at all. One suspects that the writers simply didn't think it through -- there are dozens of examples of plots where if GL had actually employed his ring's powers to their capacity, the story would be over by page two.

Nevertheless, Alan Scott did pretty well for himself, lasting throughout the 1940's in both his own title and also headlining All-American Comics, until 1949 when he fell victim to the waning popularity of superhero comics in general. There weren't any major "re-imaginings" of his character to speak of -- he stayed pretty much the same guy throughout. You could argue that the addition of Doiby Dickles added a lighter comedic tone and changed the nature of the series, but that was so early on that I'm disinclined to count it, not even as a 'new direction.' (Especially since it was almost an industry-wide phenomenon -- Plastic Man had Woozy Winks, Wildcat had Stretch Skinner, even the Spectre had Percival Popp. Etc.) Still, you can see that the writers were flailing around a bit even then, trying to find the magic story formula that would really make the strip go.

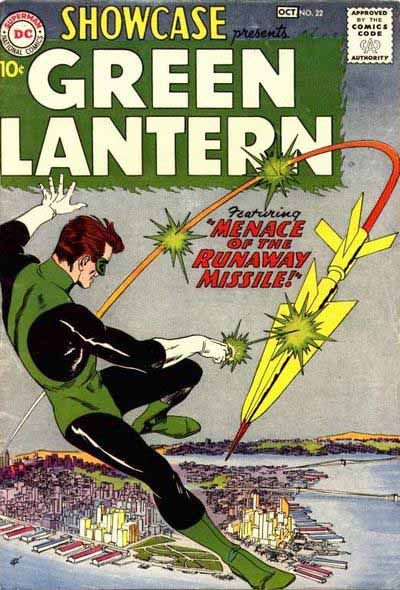

Ten years later we got the first relaunch, the Silver Age version of Green Lantern from editor Julius Schwartz and company.

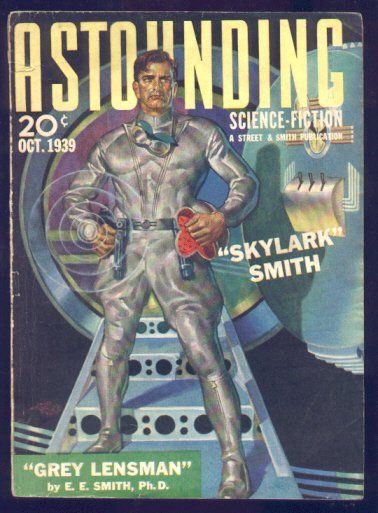

Schwartz threw out all the magical Aladdin stuff and started fresh. The only thing he kept from the original concept of the character was the name-- Green Lantern -- and the gimmick of the ring that could manifest anything the wearer wanted it to. But the series itself owed a great deal more to E.E. Smith's Lensmen series than the 1940's Green Lantern comic book. It's a pretty short hop from Doc Smith's Gray Lensman to Schwartz's Green Lantern.

Like the Lensmen, the Green Lantern Corps were a galactic force for peace and justice. Instead of a Lens that served as a telepathic amplifier, Green Lanterns were given a power ring that amplified the bearer's willpower. (In fairness, I have to add that both Julius Schwartz and John Broome denied they were thinking of the Lensmen when they created the Green Lantern Corps. On the other hand, it's hard to believe that Schwartz, especially, wouldn't have made the mental connection between the two, considering that he knew Doc Smith personally.)

At any rate, the revived GL strip itself was a textbook example of Schwartz's gift for blending superheroics and science fiction... to my mind, the Silver Age Green Lantern is probably the most fully-realized example of the classic Schwartz science hero. Earthman Hal Jordan, "honest and fearless," is drafted into the Corps when the Green Lantern assigned to protect our sector of space crash-lands in the desert. Soon he finds that he is now part of a galaxy-spanning police force recruited from hundreds of different worlds.

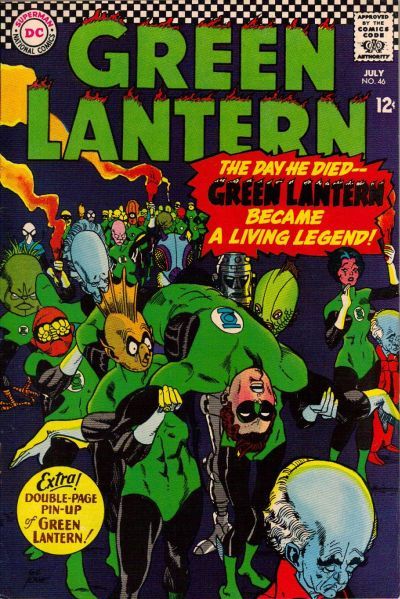

The concept was a winner and Hal Jordan soon got his own book, as well as membership in the Justice League. One of the strongest things the book had going for it was the idea that Hal was just one of many GL's scattered throughout the galaxy, and stories that included other members of the Corps were always popular.

Nevertheless, sales dropped after a few years and again, the tweaking started. Hal Jorden started as a square-jawed, Yeager-esque test pilot, brimming with that New Frontier spirit... the perfect hero for the dawning Space Age. But -- one assumes in an effort to shake things up -- Hal had one crisis of confidence after another. Writer John Broome kept changing Hal's private life, giving him new jobs (and occasionally girlfriends) but nothing seemed to work. Again, none of these things were full-on relaunches, but nevertheless there was a certain air of behind-the-scenes panic that hung over Green Lantern in the mid-to-late sixties. And again, the power ring itself is de-emphasized. (At one point Hal even decides that he is depending on it too much, and vows to use his fists more.)

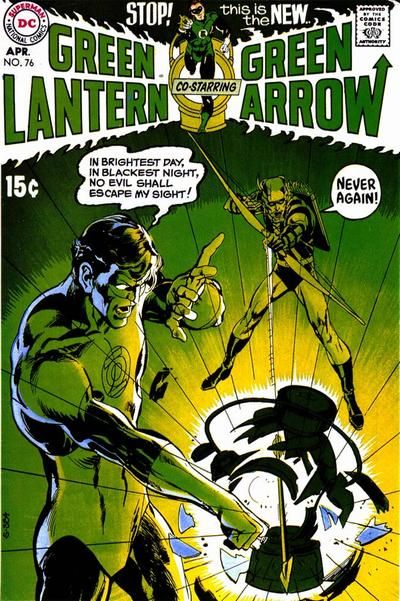

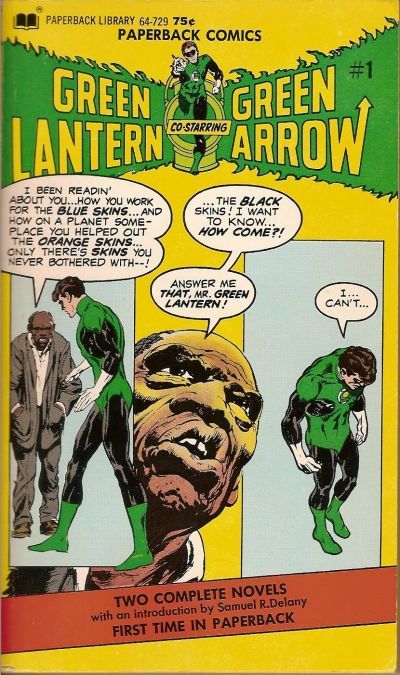

None of these new directions really stuck, and Schwartz finally decided it was time for a full-on revamp of the book, with a new creative team. The character of Green Arrow was added and it became a team book instead of a solo. Additionally, the stories focused on "real life issues." These changes are extensive enough that I'd call it a relaunch.

A great deal has already been written by comics scholars about the groundbreaking run of stories that Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams did on Green Lantern/Green Arrow, and certainly their place in comics history is an important one. However, I'm not really interested in going over how the new, "relevant" focus of the book put "superheroes in the real world" or anything like that.

The truth of the matter is that as innovative as the new approach might have been -- and it was every bit as groundbreaking as people said -- in light of the actual Green Lantern concept, it comes off as a bit silly in hindsight.

In Denny O'Neil's earnest attempts to dramatize the real-world issues he wanted to focus on, he often portrayed Hal Jordan as weak, full of doubt, and occasionally just flat-out stupid. (I find it almost impossible to believe that as a member of the spaceborne Green Lantern Corps, Hal Jordan had never encountered anyone asking him to use his power ring to alleviate poverty before, or even that the confident, fearless Hal wouldn't have a ready answer for the crabby old black man bugging him about it.) Eventually the reader starts wishing Hal would just get over himself, demonstrate some of that fearlessness and willpower we've been told he's famous for having, and kick some ass already.

Anyway, despite all the accolades and awards, the bottom line was-- the new direction didn't save the book from cancellation. Green Lantern ended with #89. A pretty fair run, and more than Alan Scott had managed.

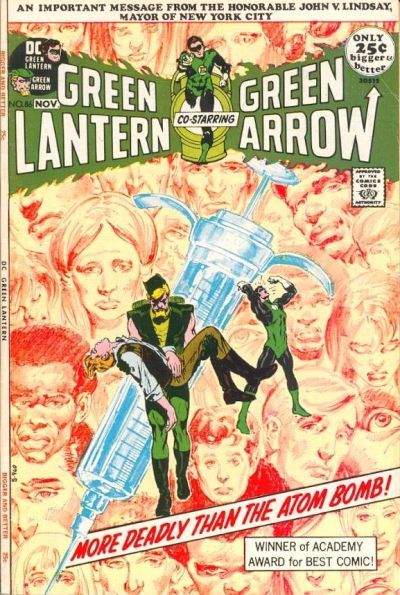

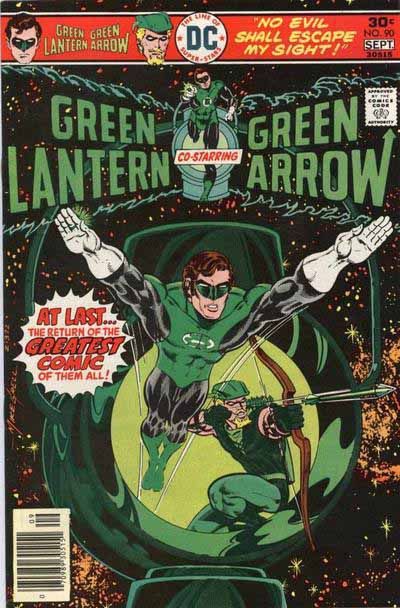

A few years later the book was revived again, still with Hal Jordan and co-starring Green Arrow, but this time with more of a focus on the science-fiction adventure the Schwartz-Broome version was founded on.

It did moderately well, but in the same way that it doesn't make a lot of sense for Green Lantern to be so earthbound, it didn't really work to have Green Arrow in the outer-space milieu, either, and he often came off as looking a bit useless.

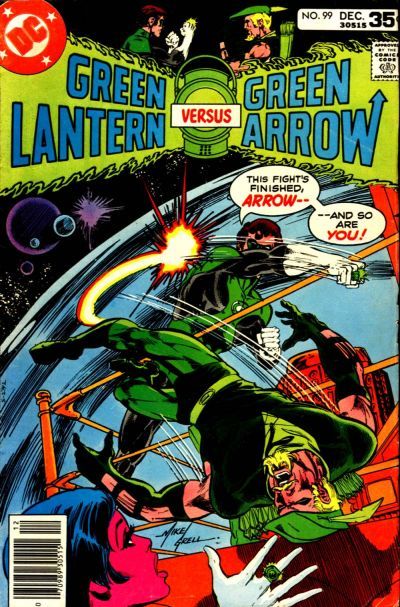

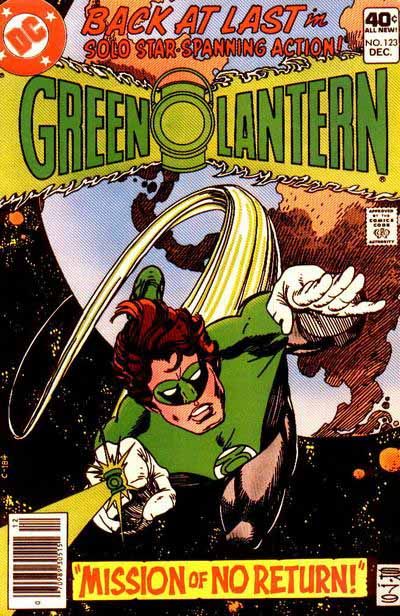

After a couple of years of stuttering along without much of a direction, it was decided that Green Lantern should be a solo title again.

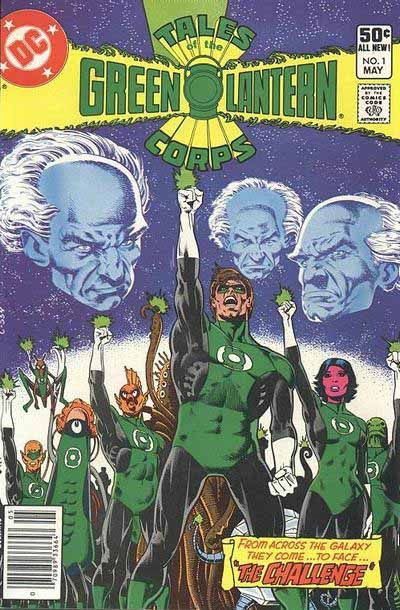

The emphasis was back on space adventure and the GL Corps, who got a series of backup strips and occasionally their own spin-off special.

However, the book still blew hot and cold and no one really was able to figure out how to make it go. There were good stories and memorable runs -- for example, I rather liked what Marv Wolfman and Joe Staton did during their tenure -- but nothing lasted, the book never felt like it stabilized. Hal went through another series of jobs and girlfriends before he was back at Ferris Aircraft as a test pilot, having come full circle -- Hal's revamped status quo was actually the one he'd started with.

This started Green Lantern's pendulum swing between 'startling new direction!' and 'getting back to basics!' that's dogged the title to its present day, in all its incarnations. Hal was exiled to outer space...

Then he came home....

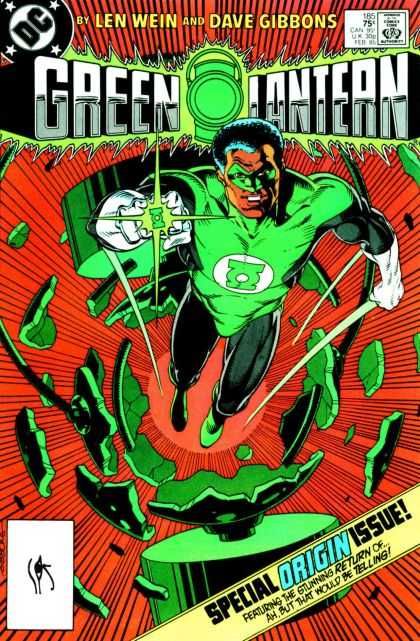

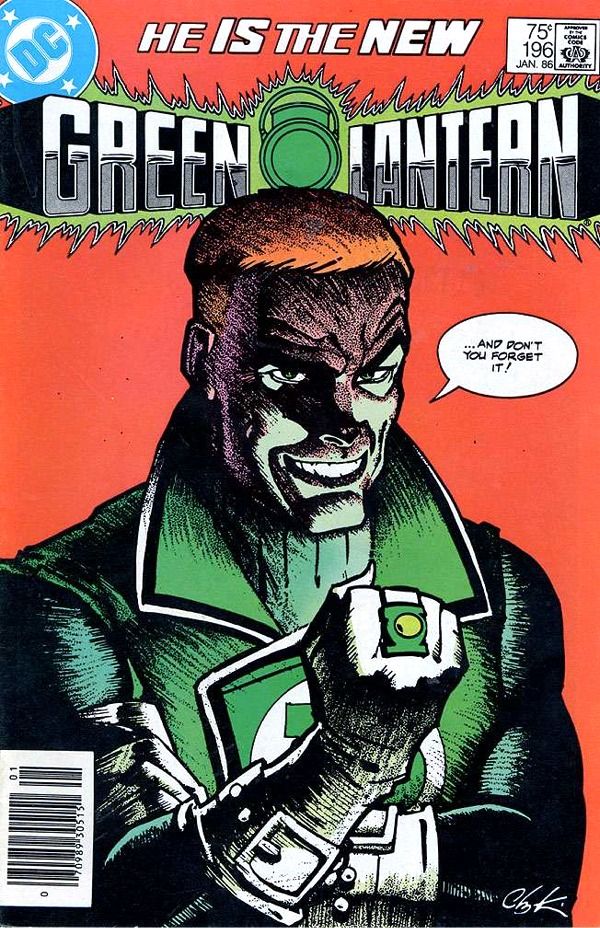

Then he was replaced by John Stewart....

Then Guy Gardner was made a Green Lantern in addition to John...

Then Hal Jordan was reinstated but John and Guy both stayed too and it became a team book...

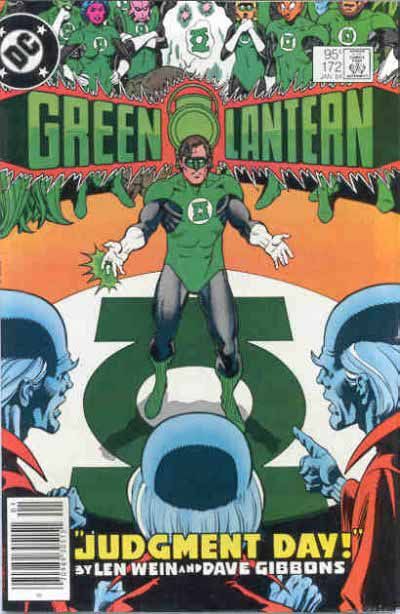

And so on. Now, a lot of these stories were great. And the Wein-Gibbons stuff, followed by the Englehart-Staton run, really was a pretty stable era for Green Lantern. It lasted from #172 all the way up through #224, fifty-some issues and a couple of Annuals. And it's actually my personal favorite of all the different incarnations of the series.

But I have to admit that even though the various changes to the book's premise felt natural and organic at the time (Steve Englehart's scripts, especially-- each change he made seemed to grow out of the previous one) nevertheless, over the course of those fifty-plus issues there were still dozens of changes to the book's cast and there were at least two different times I'd call those changes full-on reboots. That's a lot of tweaking.

Then DC decided that it would use the success Englehart and Staton had achieved on Green Lantern to anchor its relaunch of Action Comics as a weekly anthology title.

The trouble was, Englehart and Staton didn't want to do the strip in that format and so Green Lantern foundered again. Lots of different writers and artists followed, many of whom made changes that seemed aimed directly at undoing everything that had been done by the previous creators. Supporting characters killed off, Hal's private life revamped, all the old standbys were trotted out in an effort to get readers to pay attention. It stank of desperation, it was a mess, and by the time the Action Comics Weekly experiment was done, I think Green Lantern fans were largely just relieved it was over. Certainly I was.

After a hiatus of a few months and a couple of one-shot specials, the Green Lantern concept was dusted off and given a brand-new relaunch in the 6-issue Emerald Dawn, a mini-series in the spirit of DC's other "Year One" flashback stories that were doing well.

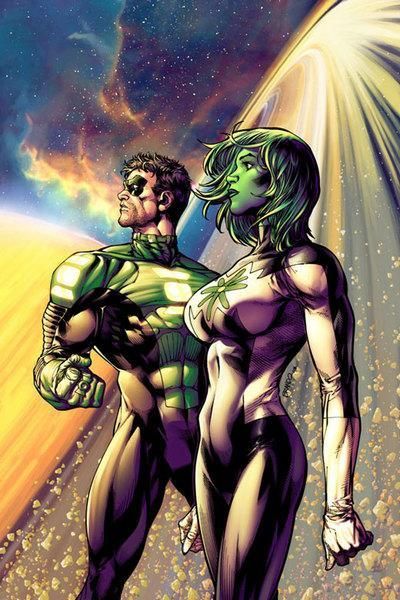

The pendulum had clearly swung to the Back-To-Basics side of the equation again; the emphasis was squarely on SF space adventure and the galaxy-spanning GL Corps. Shortly after that, Green Lantern was launched again, this time as a sort of rotating-roster team book variously starring Green Lanterns Hal Jordan, Guy Gardner, and John Stewart, as well as new characters like the canine G'Nort.

This was, again, a successful version that spun off into several different titles, largely under the careful stewardship of writer Gerard Jones.

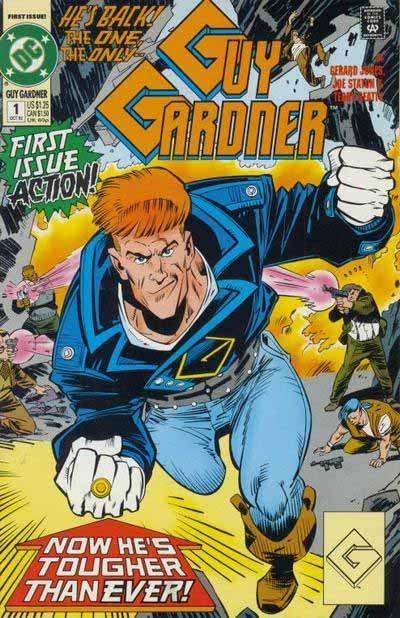

Even after Guy Gardner was kicked out of the Green Lantern Corps, he was still popular enough to get his own series and continued as a member of the Justice League.

A lot of these spin-offs and relaunches were experimental, particularly Mosaic, but still based on the idea of the Green Lanterns being a galactic peacekeeping force having adventures in a science-fiction milieu.

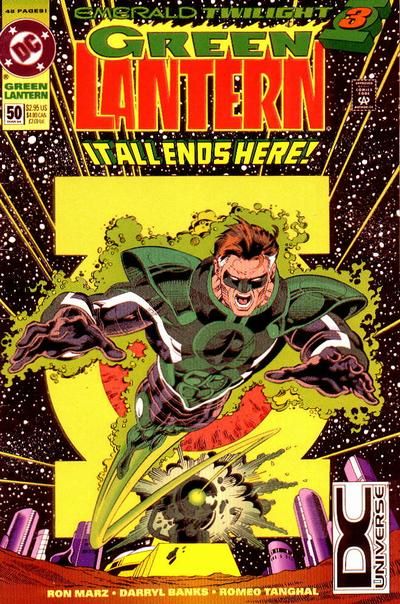

Then came The Controversy. You all know which one I mean.

In a move that to this day I don't entirely understand, DC gave editor Kevin Dooley a mandate -- they decreed that the entire Green Lantern concept was outdated and needed to be drastically revamped in hopes of drawing in a new audience. I'd have thought a relaunch that did well enough to justify three companion titles was good enough, but apparently not; sales on the books had been slipping.

However, judging from interviews and reminiscences from the people involved in the years since, I think part of it was a desperation money grab. Remember, this was 1994. Everyone was looking for the next "Death of Superman" speculator bonanza. The hope was to create a big publicity storm, then cash in when there was a collector's run on the book. Story was hardly a consideration for superhero publishers in the early 90's. Not when Todd MacFarlane's Spider-Man and "Death of Superman" showed you didn't need a story to make money. You just needed "buzz."

Gerard Jones submitted an idea for a new direction that would climax in the 50th issue of Green Lantern but it was decided that it wasn't interesting or shocking enough to generate any buzz. Enter new writer Ron Marz and the infamous "Emerald Twilight," the story that destroyed the Green Lantern Corps, killed the Guardians and turned Hal Jordan evil.

Confession time -- I am not one of those Green Lantern fans that goes into paroxysms of rage when the subject of "Emerald Twilight" comes up. For one thing, I have to be honest...in my case, the story did the job DC wanted it to do. I hadn't been reading the book and curiosity about all the furor got me to pick it up again, and it was interesting enough for me to stick with it.

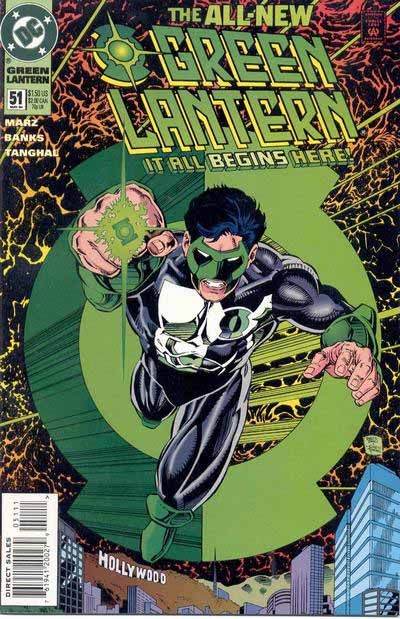

I kind of liked the idea of a fresh start. Even though I'd grown up with Hal Jordan, he was my favorite DC character other than Batman, and Green Lantern had co-starred in the first comic book I ever bought... even so, I was willing to buy into the idea that a new lead character in the role could revitalize GL the same way installing Wally West had revitalized The Flash. I thought it was worth a look.

Also, I had the opportunity, that summer of 1994, to chat with Ron Marz at a show here in town and hear his thoughts on the approach he hoped to take with the book. It was still early enough in his run that he wasn't exasperated with having to explain himself to Hal's fans, and the case he made for having just one Green Lantern that was unique, as opposed to a corps of 3600, was a pretty good one. I still think DC threw the baby out with the bathwater there-- I discovered, reading "Emerald Twilight," that I was far more attached to the the concept of the GL Corps than I was specifically to Hal Jordan-- but I did come away from that conversation persuaded that even though I missed the idea of the Green Lantern Corps, nevertheless Ron Marz was a guy who was putting serious thought into what he was doing and trying his damnedest to bring his A-game. (As luck would have it, there's a retrospective with Mr. Marz covering a lot of this stuff right here on CBR.)

So I stuck with Ron Marz, Green Lantern and Kyle Rayner for quite a while and enjoyed the experience, for the most part. It wasn't my Green Lantern, exactly, but it was good solid superheroics, reliably entertaining, and back when comics were cheaper that was enough for me.

Interestingly, for a writer who's generally only mentioned in GL fan circles as being "that heretic who destroyed Hal," it's worth mentioning that Ron Marz was remarkably successful. In spite of all the rage from internet campaigns and groups like H.E.A.T., not only did sales on the book rise to where it was one of the top titles at DC, but Marz was on Green Lantern longer than any other writer to date. Ron Marz did Green Lantern from #48 to #125, and that's not even counting the additional mini-series and specials and so on. Well over seventy-five issues, quite a respectable run.

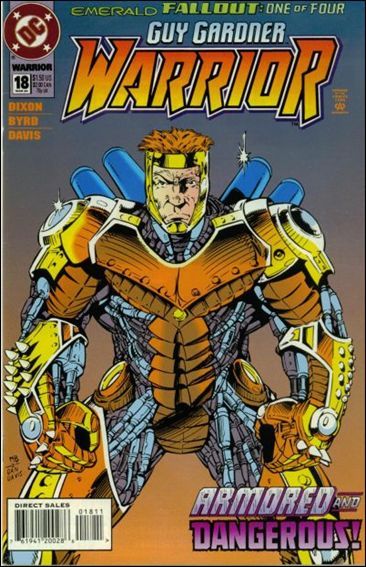

However, despite the fact that I think Ron Marz is unfairly vilified for his Green Lantern work a lot of the time, I have to admit that the new direction (with its mandate of making Kyle Rayner the only Green Lantern left in the DC universe) did a lot of collateral damage in terms of the revamps it forced on the other characters in the GL orbit.

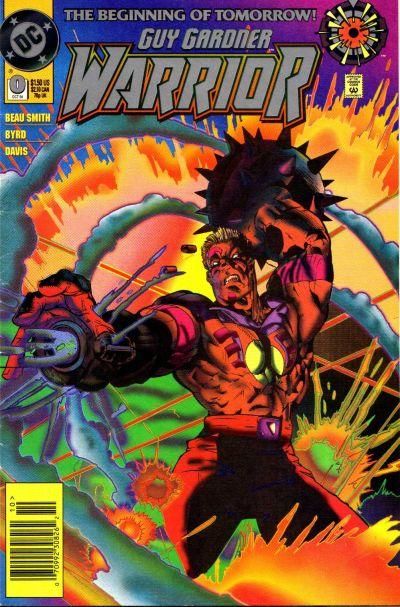

Guy Gardner, in particular, suffered the worst kind of 'bold new direction!' indignities as DC tried to decide what the hell to do with him, before his book finally staggered into cancellation.

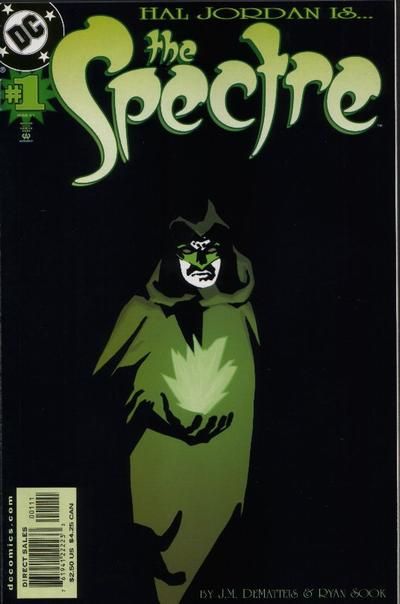

Likewise, Hal Jordan bounced around for a while as the recurring villain Parallax, then he was killed in The Final Night, then he was relaunched as the new Spectre, a move that was even more muddle-headed than the decision to make him a villain had been.

I confess that, as baffling as I found the decision to give fearless test-pilot Hal Jordan a breakdown that turns him into a murderous villain, it's not nearly as nutty as following it by turning him into a mopey ghost. DC managed to alienate both the Hal fans and the Spectre fans in one stroke. What were they thinking?

I won't bore you with all the additional various ancillary Green Lantern revampings of characters like John Stewart or Jade or Sentinel... this is already getting too long as it is.

Suffice it to say that to an old-school Green Lantern fan, the characters and even the core concept of the series had morphed into something almost unrecognizable.

When you get that far away from where you started? Why, it must be time for... c'mon, you know the words, sing it with me! "Getting Back To Basics."

Again.

And so the pendulum swings back once more. I have to admit that when I started this I hadn't quite realized how thoroughly the GL concept had been revamped, retconned, and generally mauled by various editorial regimes through the years.

And it's not even the worst example -- but I think it would take a book's worth of synopses to try and account for similar changes in direction for, say, the X-Men over the last twenty-five years. Or the Hulk. Or the Teen Titans. Or... pick your own candidate.

After all that, I still don't have an answer for Mr. Bosnar. Not really. Why do people keep tweaking a perfectly good concept? Why mess with a good thing?

The best I can do is a guess, and here it is: times change and audiences get bored. Sooner or later, even the most popular series runs out of gas. So the only reason to do any kind of a revamp or a relaunch is because you think you can get a bigger audience. The only reason.

However, and here's the part that drives us all a little nuts -- unlike other entertainment franchises, superhero comics are aimed at an audience of hobbyists who regard these stories not so much as light entertainment, but rather as historical dispatches from an alternate universe. What I see when I look at the history of all these different versions of Green Lantern is this -- the common factor to all of them is writers laboring under the lunatic misconception that this fictional entertainment really is history.

That's a handicap that forces creators to twist themselves into knots to get over. Unlike, say, the James Bond movies which have reinvented themselves a number of times without any thought to what came before, or licensed Star Trek books and comics that contradict one another right and left, comics fans insist that their superhero relaunches must all somehow acknowledge and account for everything that's been done up to that point.

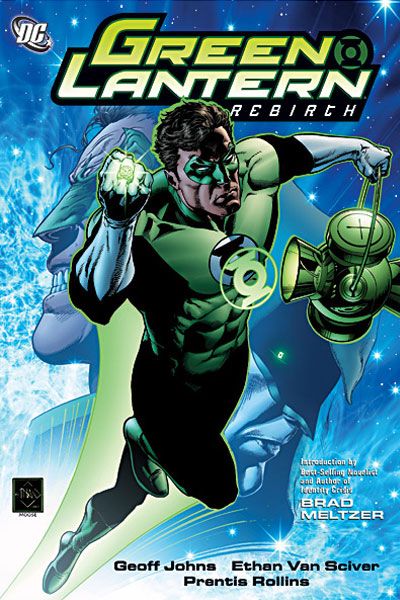

So you can't just do a new Green Lantern series from scratch, not the way Julie Schwartz did it in the late '50's. No matter what fresh angle you might bring to the idea, first you have to somehow doubletalk your way into a rationale for doing it. Maybe it's having Hal Jordan go nuts so you can replace him with Kyle Rayner, or having Kyle step aside and Hal come back from the dead so he can be GL again and not the Spectre. That's where these incredibly pedantic, minutiae-driven series like Green Lantern: Rebirth come from. We can't just start with "Brand New Day," we have to have "One More Day" first.

DC seems to think so, anyway. Honestly, I doubt that it's really the case. Fans have shown that they'll go along for the ride and never mind continuity if it looks to be a ride worth taking: DC's New Frontier, Marvel's Ultimate books, All-Star Superman.

Maybe the question isn't so much, why keep tweaking the good idea? Maybe the question should be, why not just do the new version instead of first killing yourself trying to appease all the fans of every previous version ever?

Because you won't ever appease those fans. It can't be done. No matter how awesome your new take on their old favorite might be, they'll still call you a heretic. But in trying to humor them, you inevitably will be boring the pants off any new folks who might have happened by to give the revamped version a look.

For example, I'd love to see new versions of the Flash, or Aquaman, or any of another half-dozen superhero concepts that I think still have plenty of miles on them. But I'm not really interested in reading the in-continuity justification for doing it-- especially this current DC trend of doing a six-issue series to explain how you are about to start to do a new ongoing series. That's really a case of the snake swallowing its own tail. So many DC superhero comics seem to be in the business of simply setting up other DC superhero comics that it's become ridiculous. You know, give me a call when the story actually starts.

By contrast, even though Marvel has gotten a lot of flak over the years for being continuity-obsessed, I gotta give them credit. They do Marvel Adventures Avengers side-by-side with The Ultimates and neither one of those has anything to do with New Avengers, or Mighty Avengers. Each series has its fans and no one seems to have any "continuity" issues with any of them. We really are smart enough to keep up and I appreciate Marvel's willingness to gamble on that.

I don't actually mind when a publisher decides to slap a new coat of paint on an old franchise and give it another try. What I find tedious are the ridiculous attempts to explain in the story itself why it's okay to do it. It's a ball-and-chain that writers simply don't need to drag around behind them.

I used to think creators did this because the fans insisted on it, but the more I think about it, the more I consider all the successful examples of the times readers rewarded creators who said screw it, the hell with continuity, let's go... the more I think this handicap is something self-inflicted by nervous editors.

Honest. If the story's good enough, we really won't care who or what you contradict. How many more times do you need readers to demonstrate it?

See you next week.