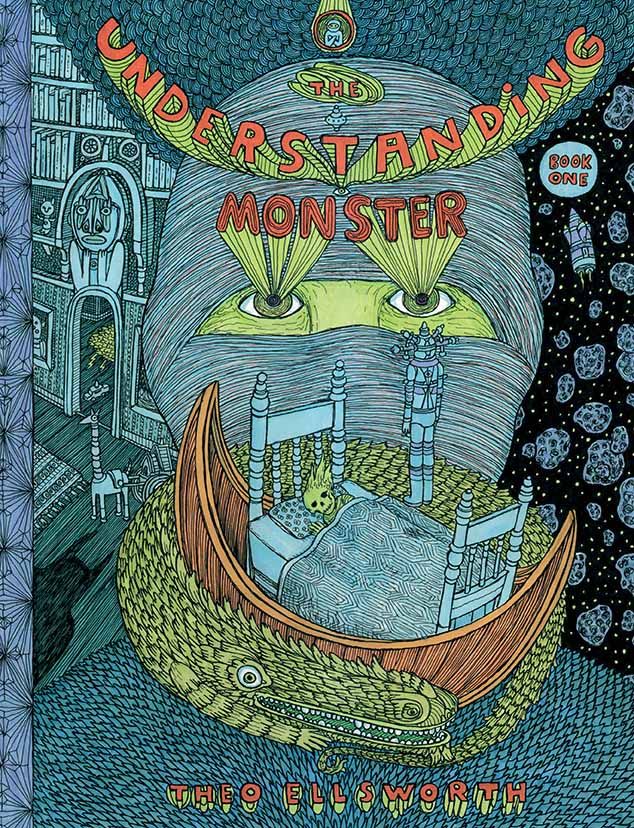

The Understanding Monster Book One

Secret Acres, 72 pages, $21.95

by Ron Rege Jr.

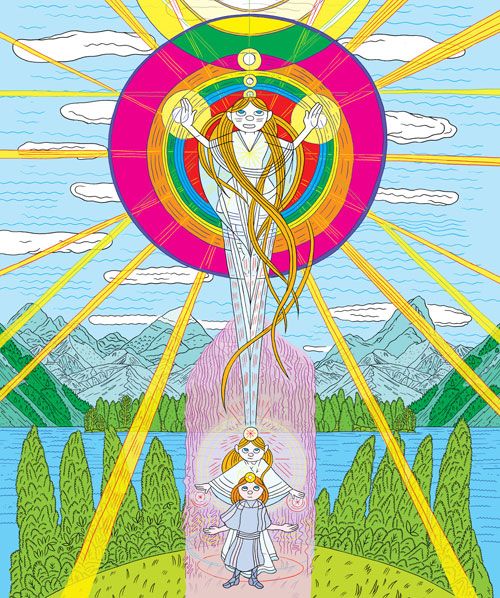

Fantagraphics Books, 144 pages, $24.99

"Hey Izadore! I've just realized that you have microscopic tribes of violent spore lords living on the surface of one of your eyeballs! One eye is at war with the other and both sides have been using your brain as a nightmare particle factory and fueling their attack vehicles with your blood! What are you going to do?"

What are you going to do indeed? So goes a sample of dialogue from Theo Ellsworth's latest book, The Understanding Monster, the first volume in a projected three-book series. As the above excerpt might suggest, this is a trippy, almost hallucinatory comic, given to frequent bouts of digression. There's a temptation to call it psychedelic, although that seems too limiting. Suffice it to say that that it's an experience utterly unlike any other comic that's out right now.

Any attempt to describe the plot is an exercise in frustration. It's ostensibly about a mouse (maybe) named Izadore (possibly) that is attempting to cross a room filled with toys (I think). Along the way he's encouraged by friendly and not so friendly creatures and beasts that either attempt to encourage him on his journey or prevent him from moving forward. Along his physical and psychic journey, the mouse regresses to past lives and experiences, turning into an old man in bed (maybe), a mustachioed man with a detachable, floating head (conceivably) and a mummy (perhaps). One scenario morphs into the other, often in a jarring, bizarre manner. This is a book that defies easy synopsis.

What is clear in this book is the idea of progression, of making some sort of journey (internal? external? both?) despite being crippled with anxiety and self-doubt. There's a palpable sense of therapy, of self-actualization that informs the book. Izadore's friends are constantly encouraging the mouse to keep moving forward, despite being plagued by all manner of demons and pug uglies that whisper defeatist, paranoid and nightmarish things ("I have the power to give people diseases just by looking at them, and I'm staring at you hard," whispers one ghoul. "You have a trained group of specialists working against you," says another. While it's hard to figure out what exactly Izadore is moving towards, there is little doubt that it is essential that he keep advancing, that stasis equals death, or worse, unfulfilling your ambitions.

Despite a layer of inscrutability, Understanding Monster remains a fascinating and enjoyable, if at times head-scratching and forbidding book. Never one to adopt the term "minimalist," Ellsworth fills every page, every panel with as much detail as possible. Oddball characters whisper secrets to the protagonist from the margins. Subtle and intricate hatching and other patters fill the walls, the borders, the character's faces and fur. Even thee back cover -- a pile of toys and odd-looking gee-gaws threaten to spill out into the reader's lap. Understanding Monster is like some odd alien frequency that, although foreign, is so unique and pleasurable that you can't help but let it wash over you.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of The Cartoon Utopia, another ambitious, seemingly psychedelic graphic novel, this time from Ron Rege Jr. Like Understanding Monster, Utopia creates a cluttered, seemingly forbidding universe and beckons the reader inside, but while the visual ride is a stunner, the substance seems somewhat lacking.

Though his previous books (most notably Skibber Bee Bye) can come off as bleak, Rege has always been a romantic, wears his heart on its sleeve as a badge of pride. His previous books have centered on the need for connection, friendship and a physical and spiritual healing. Is it any wonder that the title of his 2008 short story collection was Against Pain?

In many ways Cartoon Utopia is a culmination of those themes, with Rege drawing science, new age spiritualism, the occult, astrology and Jungian archetypes to come up with a personal grand unification theory. There are no plots or characters in the book to speak of, instead Rege merely muses and illustrates his theories, which mainly have to on the interconnectedness of all living matter ("Humanity is one single being that has been separated into individual entities to fully experience physical creation"), how sound and vibration can affect our well-being ( and the need to draw upon love and kindness in order to live a fulfilling and purposeful life ("Love is the harmony that our particles make together"). In other words, Rege is just a big ole' hippie.

It's tempting to dismiss all this (as I did just now) as a bunch of amorphous, ill-thought out nonsense but it's important to stress how dead serious and utterly sincere Rege is being here. What's more, he's clearly done a considerable amount of esoteric research for this, and at times references Wilhelm Reich, William Blake, Otto Mesmer and even Sun Ra (the Sun Ra sections are the most entertaining parts of the book).

But while his sincerity cannot be questioned, I found myself unable to fully engage with Cartoon Utopia. As much as I can sympathize and even agree with parts of Rege's manifesto, I found my self doubtful or even unintentionally scoffing at some of Rege's more grandiose notions, particularly the idea that creating a utopia on earth is not only possible, but will result in a world where everyone rides around on a giant floating machine (no, I did not make that last part up). It's probably the cynic in me, but I found the heart of Rege's "love will save us all/time has no meaning" thesis to have a layer of banality at its core.

But if Rege's theories seem a bit too half-baked for me to swallow, the art is nothing short of captivating. Rege has always been given towards abstraction, but here he goes all out, his blocky, basic-shapes characters all but hidden midst a plethora of intersecting lines that often radiate outward, the better to connote a feeling of enlightenment. Even the text becomes part of the game, with big, blocky letters overlapping and piling on top of each other and traversing this way and that. It can be extremely difficult to read at times -- Cartoon Utopia requires your full attention, make no mistake -- but I've never seen an artist attempt to integrate the art and text in such a manner before and I'm grateful for the experience.

It's clear that both books are very personal projects for their respective authors. But in the end I think Monster ends up being the better book, perhaps because it is not trying to insist that everyone adopt its topsy-turvey worldview, but merely linger upon it for a few moments.