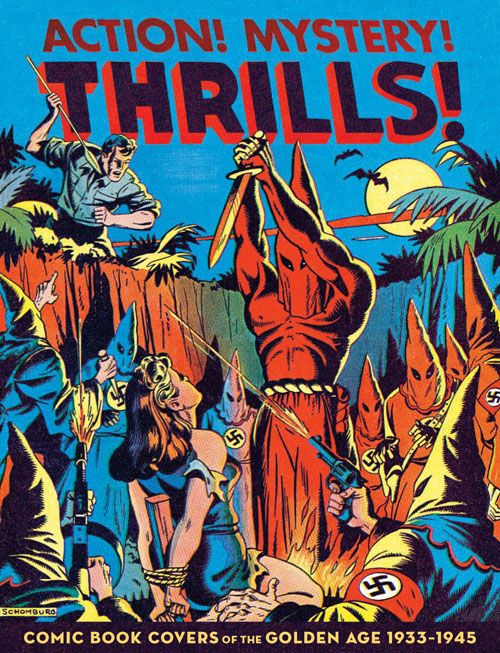

Action! Mystery! Thrills!: Comic Book Covers of the Golden Ages, 1933-1945

Edited by Greg Sadowski

Fantagraphics Books, 208 pages, $29.99

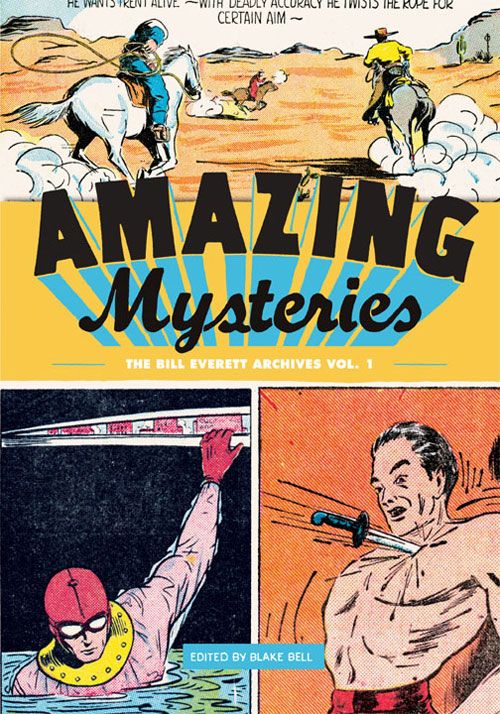

Amazing Mysteries: The Bill Everett Archives Vol. 1

Edited by Blake Bell

Fantagraphics Books, 224 pages, $39.99

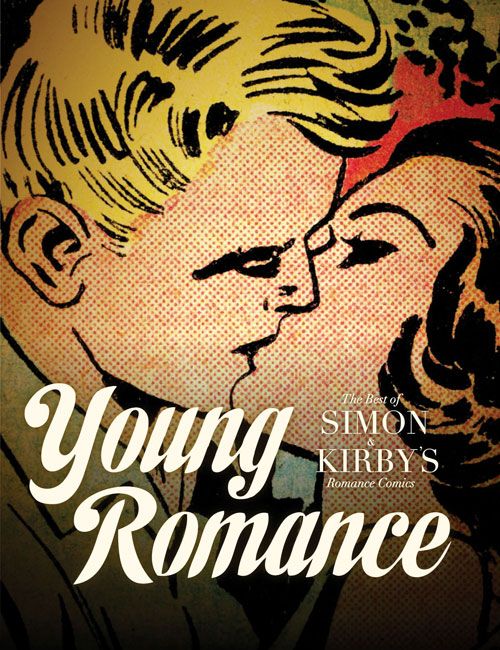

Young Romance: The Best of Simon & Kirby's Romance Comics

Edited by Michael Gagne

Fantagraphics Books, 200 pages, $29.99

Our current publishing era has been dubbed the Golden Age of Reprints by a number of online pundits, myself included, and it's not too hard to see why. Classic comics that fans and scholars never thought would make it to the bookbinders, let alone be available in an affordable version, are now coming off the presses at a staggering rate.

One of the benefits of this plethora of reprint projects is it allows us to re-examine certain noteworthy periods of comics history, help us discover long ignored artists and fully consider cartoonists who, though their names might have been recognizable, have largely been unappreciated except by a few. The alleged Golden Age of comics in particular has benefited from this scrutiny, not only in illuminating people like Fletcher Hanks but in showcasing work by folks like Jack Cole and Bill Everett.

One of the people leading the way in this specific endeavor is editor Greg Sadowski, who, in anthologies like Supermen! and Four Color Fear, has given average readers access to comics from well-covered eras (i.e. the early superhero and horror trends) merely by republishing stories that didn't come from Marvel (or whatever it was called at the time), EC or DC.

Sadowski's latest book, Action! Mystery! Thrills! has a somewhat even narrower focus, dealing entirely with comic book covers from the Golden era. It makes a certain amount of sense. While covers are still an integral part of marketing and selling a comic, they were even more essential back in those early, heady days, when you competed with hundreds of other titles and an eye-catching cover could mean the difference between profit and cancellation (or at least that's what many editors and publishers of the time felt).

If you've read any of Sadowski's collections before, you should be familiar with the format by now. A short introduction or forward, followed by the work in question, uninterrupted by commentary, which is usually saved in the back of the book in some sort of "notes" section.

That's certainly the case here as Sadowski peels through an assortment of covers, both notable for their historical significance as well as their aesthetic traits. A number of well-known artists are featured prominently here, including Will Eisner, Walt Kelly, Jack Cole, Lou Fine, Mac Raboy and Charles Biro. He seems to have a special fondness for the work of Alex Schomburg, a Timely/Marvel artist whose work mainly consisted of heroes leaping into action just as the barely dressed damsel (and perhaps a sidekick or two) was about to some horrible violent fate, usually involving elabore machinery and/or knives, from a gang of hooded evil-doers.

Honestly, while I can see the appeal in Schomburg's frantic, almost cartoonish designs, I found myself preferring Cole's elegant compositions or Raboy's stately, illustrative offerings to Schomburg's overly busy, cluttered covers, where it seems something had to be happening in every single corner lest the eye have a moment to rest.

And while I enjoyed Thrills (I'm especially grateful for being exposed to the neon-color stylings of L.B. Cole, who seems to prefigure the era of black velvet paintings), it's definitely the slightest -- the most coffee tableish -- of Sadowski's books so far. It feels like a book designed more to flip through than to mull over. Even Sadowski's notes seem less considered and more perfunctory than before. That's not necessarily a bad thing -- there's certainly pleasures to be had in re-examining these covers, as garish as some of them are -- but it does make it a lesser star in the reprint galaxy.

As one of the pioneers of the comic book format, naturally Bill Everett is featured prominently in Thrills. He takes the starring role, however, for the Blake Bell-edited Amazing Mysteries, the first in what I assume is to be a multi-volume collection of the Sub-Mariner creator's non-Marvel work, much in the same way Bell has been collecting and packaging Steve Ditko's early material.

Bell keeps things in mostly chronological order here, although he does organizes the "chapters" according to the different characters Everett created, like Music Master, Hydroman and the disturbingly androgynous Dirk the Demon.

What's exciting for me about this book is watching Everett develop as an artist and storyteller and figure out the medium in relatively rapid fashion. His lettering, clunky and stylized in his initial Skyrocket Steele story, quickly more straightforward and easier to read. His composition becomes more assured and dramatic. He clearly starts thinking of the page as a unit and not a bunch of unrelated panels as they stories start to seem less cluttered and more refined.

The heroes themselves seem an odd mish-mash that belong more to the "maybe this will sell" school than anything else. Everett rarely spends more than a story or two on any particular character, jumping from the generic spaceman Steele to the generic cowboy Bullseye Bill to the oddly dressed but still generic superhero The Conqueror, with little seeming thought between the various adventures except how best to depict the action.

Everett's interest clearly lied with some of his more eccentric creations. Hydroman, for instance, is a obvious favorite. As a precursor to the Sub-Mariner, he's certainly a figure many historians draw attention towards (apparently Everett had a thing about water). Dressed in a bulletproof cellophane outfit, Everett clearly got a kick out of depicting Hydroman in a variety of aqua-based scenarios -- a glass of water here, an ocean liner there -- and and frequently draws him in in the middle of a transformation as he rushes out to surprise and subdue the bad guys, the rough water lines literally and figuratively coalescing in the panel to form a human figure.

That fluidity also graces Music Master, a hero who can transform himself into literal sound waves, with a string of notes trailing behind where the lower half of his body should be. Perhaps the oddest creation, though, is Amazing-Man a seemingly invulnerable (and at times invisible) character who gets his powers from an unnamed Eastern cult who goes from battling whip-wielding criminals to an entire (presumably German) army. The stop and go nature of these tales, combined with the Everett's attempt at creating a continuing story arc, give the run a dream-like, off-kilter feel.

The material in Amazing in no way represents Everett's strongest work, though they do point to his potential -- those thrilling Sub Mariner stories were just around the corner. What you see here are the glimmers of an artist struggling to comprehend the potential of this relatively new medium how he can push it to match his own interests.

Two artists that certainly knew something superheroes were Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. As interest in that genre faded with the end of World War II, however, the pair found themselves looking for other material to publish and quickly hit upon the idea of romance comics, with great success.

It's a body of work that, though it took up a little over a decade, has been largely glossed over by fans in favor of focusing instead on all the musclemen in the gaudy outfits. Young Romance seeks to rectify that oversight, providing a "best of" collection from that lengthy run.

As you might expect, most of the stories in Romance rely deeply on hackneyed melodrama, clumsy coincidences and last minute changes of heart. What separates Simon and Kirby's work from their later imitators, at least at first, is that they don't feel the need to force a happy ending, and are even willing to delve into dark areas if need be. The opening story concerns a "boy-crazy" teen who falls madly in love with her aunt's suitor, only to lose him at the end because of her flightiness. A young woman in post-war Germany falls in love with an American G.I. only to realize she can't quite renounce Hitler. A woman behaves monstrously towards her mother in an effort to nab a husband from a higher social caste. And in perhaps the bleakest story in the bunch, a young woman attempts suicide when her lover is accused of a crime he didn't commit and is given the death penalty.

The book is divided into pre-Code and post-Code and there's no questions about which section is better. The latter stories are clearly scrubbed clean of anything that might give offense, and the gender roles more clearly defined, with all the women eager to become happy housewives. Even the art, rough and thick initially, gets cleaned up in the post-Code era, lest young readers be freaked out by, I dunno, too much cross-hatching.

Though modern readers may wince at some of the sexual stereotypes on display, not to mention the occasional forced happy ending, Young Romance underscores Simon and Kirby's keen storytelling skills. Adhering to a mostly six-panel grid, the duo manage to produce work that is visually arresting and dramatic, despite the fact that the violence is usually contained to the characters' inner emotions. It's also worth mentioning that editor Michael Gange's reproduction work is stellar and apparently painstaking, as he demonstrates in an appendix at the end of the book.

Kirby, teaming up with Stan Lee, would eventually take the skills he learned from these making these romance comics -- the over-the-top emotions, the dramatic plot reversals -- and apply them with great success to the superhero genre. Young Romance helps show how that transition took place. For Kirby fans and those who just love to explore comics from generations past, it's a rather essential read.