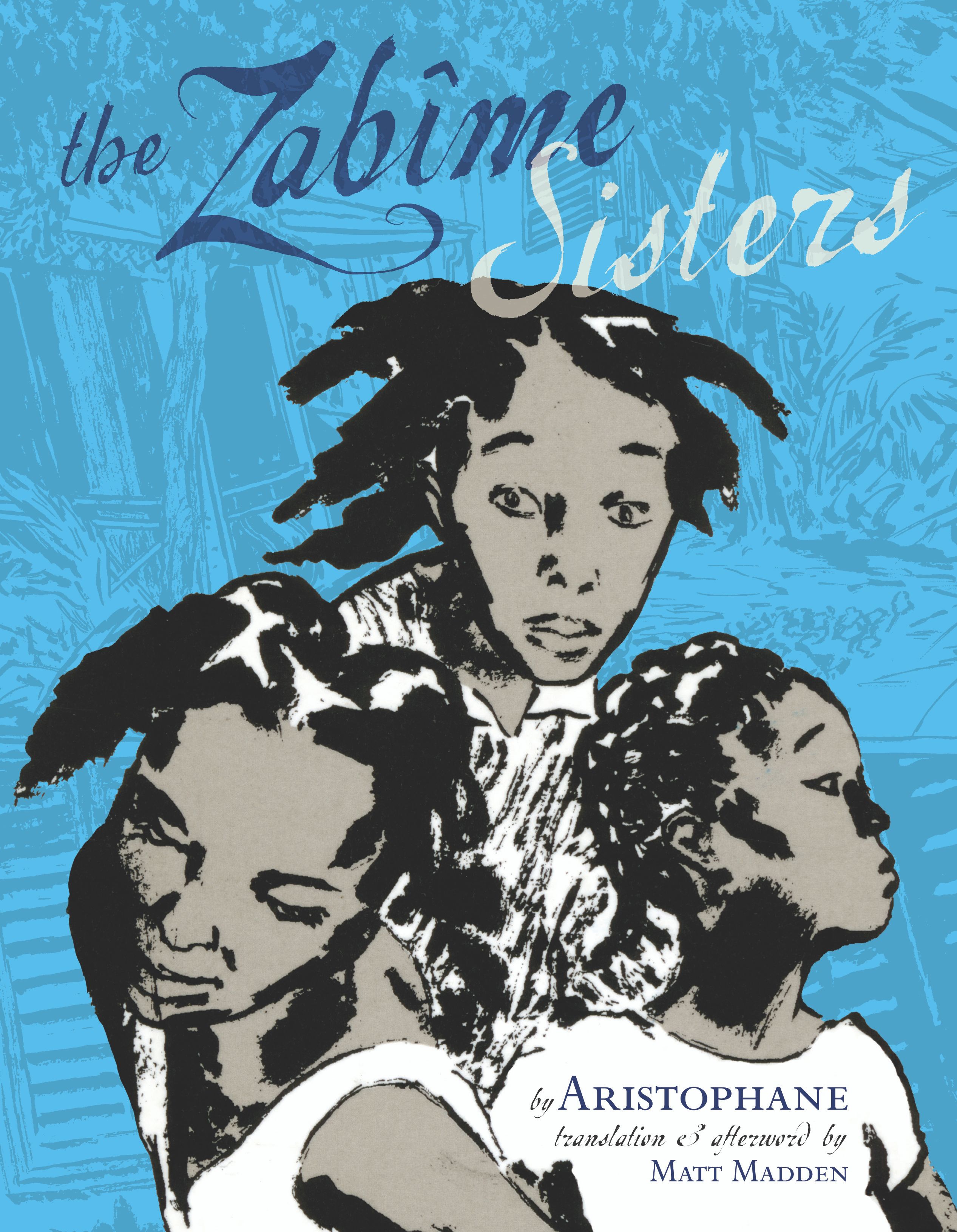

by Aristophane

First Second, 96 pages, $16.99

The Zabime Sisters follows a day in the life of three girls who live on the Caribbean island nation of Guadeloupe. That description will, I suspect, cause many readers to assume that this is a book heavy in political and social import, as we've become come to expect any graphic novel set in or focused on a culture that's not specifically North America or Eastern Europe to be some harrowing tale of life lived under a harsh totalitarian regime, poverty, colonialism, or some other real-world horror. But Zabime Sisters is not that book at all.

If there's any other comic it resembles, it might be the Aya trilogy, published by Drawn & Quarterly. Like that series, Sisters avoids simple, negative assumptions about race and culture to tell an easily identifiable story without sacrificing period details. At the same time, however, it avoids Aya's soap opera stylings in favor of something more naturalistic and meandering.

In fact, it more or less avoids any plot whatsoever. Summer vacation having officially begun, the book follows the three Zabime sisters as they spend the day exploring their neighborhood, playing in the nearby creek, climbing trees, meeting up with friends and getting into (or narrowly avoiding) trouble. They and their friends and acquaintances gossip, worry, threaten and offer advice. A potential, much-discussed fight at the schoolyard between the local bully and an unknown kid is the only object of suspense that ties the book together. Like a lazy summer day, Sisters seems content to simply follow the children wherever they happen to wander to and not push them in one direction or another too hard.

And at this point you might be thinking "Oh no, not another nostalgia-fueled, sun-dappled, Hallmark tear-stained potrayal of childhood, thank you very much." But you'd be wrong again. Not that the Zabime Sisters doesn't indulge in a bit of nostalgia -- it's clear Aristophane had a lot of affection for his cast and that he's drawing upon his own experiences here -- but it isn't trapped or weighed down by it either. Any potential wistfulness or simpering sentimentality is handily dispensed with by Aristophane's sharp observation of how children interact, think and behave.

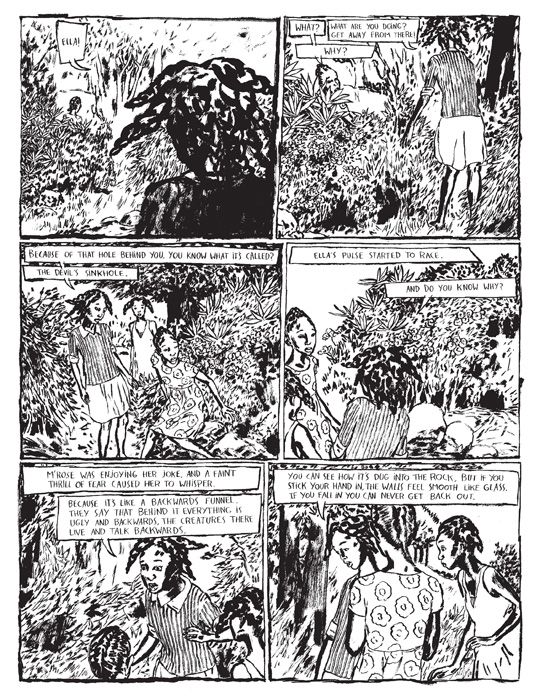

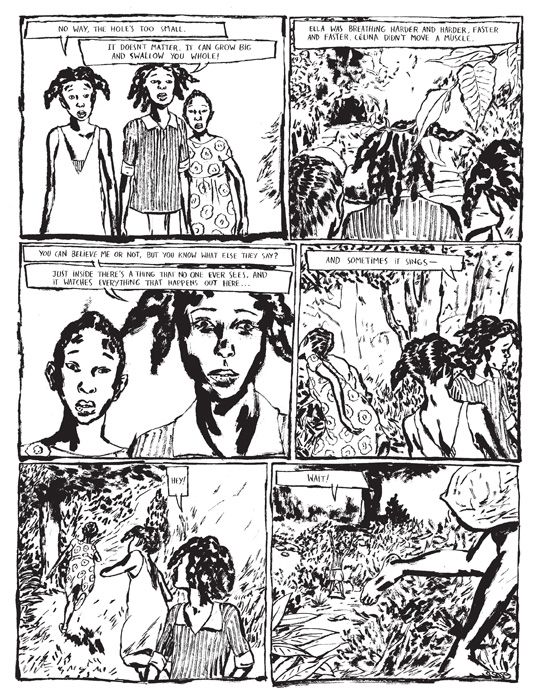

The key is the omniscient narration, which frequently clues us in on the characters' various emotional states and trains of thought while the action transpires. As a result, we discover a lot about the individual cast members -- not just the sisters, but virtually every character, to the point where the book feels less about the three girls than it does about the group of kids as a whole. Aristophane's narration picks up on their insecurities and fears (the bully, for instance, really a bit of a coward who just wants to prove himself) and thus, underscores the casual cruelty the children inflict on each other. The children in Zabime display an all-too-familiar ignorance, by which I mean not that they're stupid or uneducated, but that they seem blithely unaware of the sort of influence and repercussions their taunts and insults and rumors they spread have. Significantly, only one boy seems to have the awareness to stand apart from the fray, and he chides one of the sisters for stealing mangoes and her callousness towards a younger child.

It's telling perhaps that, except for the Mother in the beginning of the book, there are no adults anywhere to be found. They are much discussed and feared and little understood, but they are not present. Perhaps to compensate for their absence, the children in Zabime are often seem attempting to behave in what they believe are adult ways -- a lot of their actions are obviously mimicking adult behavior -- but like many kids they seem unsure and hesitant about how to best do so, and tend to mimic the bad behavior more often than the good.

I've spent a good deal of time talking about the story and themes of Sisters but not very much about the art. Which is a bit shameful of me as the art is an integral, perhaps the most essential part of the book. Employing a dry brush technique, Aristophane fills his panels with slashes of thick black ink in a manner that at first seems hurried but upon closer detail reveals a good deal of care and consideration. The way he is able to convey a worried look or the detail on a dress from a collection or rough, slashing lines is nothing short of astonishing. His splotchy panels, filled with foliage and background details, constantly threaten to become overcrowded or too busy but never do. This is one of those book that draws impressed gasps upon first opening.

This is the only work by French Aristophane that's been translated in English so far. It's also the last work he completed before dying in 2004. It seems a tragedy that it took this long to get his work overseas (Sisters was originally published in France in 1996) not to mention that someone of his artistic caliber was lost to us so soon. Hopefully the release of Sisters in America will draw more interest in him and his work. This is a deeper, more thoughtful book than first glance or a one-sentance summation can suggest. It's too knowing, too heartfelt and too honest to be dismissed.