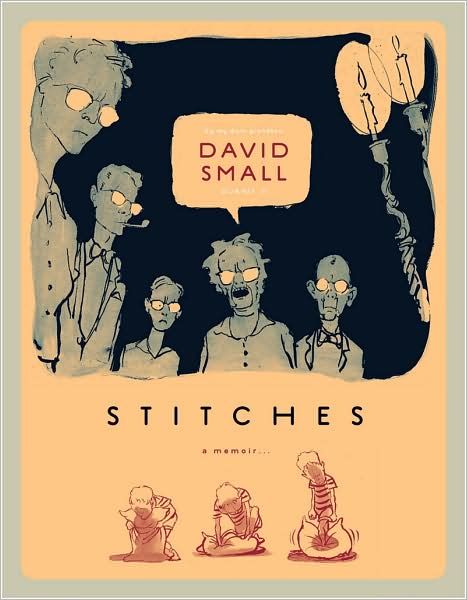

by David Small

WW Norton, 336 pages, $24.95.

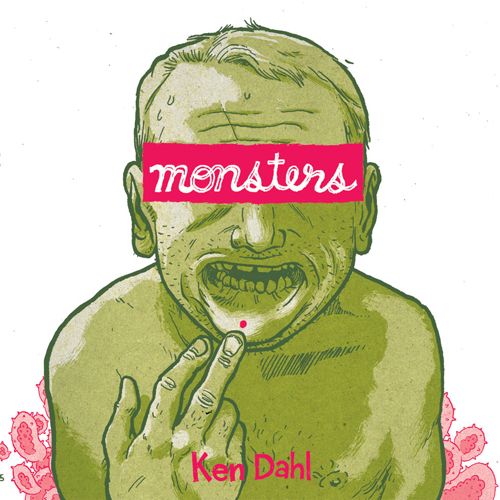

by Ken Dahl

Secret Acres, 208 pages, $18.

I sometimes suspect that part of the reason some critics (if I can use that term) are hostile towards the recent spate of comic book (sorry, graphic novel) memoirs is due to a mistrust of the genre itself. There's a tendency when someone is chronicling a dramatic, personal event, to exult praise merely for inherent drama of the story, particularly if it's a traumatic one, than the skill in the telling. Some folks, in other words, get swept up in the idea of the story itself and the bravery of the person in coming forward to tell it, and ignore whether or not the work succeeds as art.

Certainly the success of books like Fun Home and Persepolis has resulted in publishers unleashing a number of bad or mediocre memoirs on the public. So perhaps it's not surprising some folks are wary when a buzz-heavy memoir gets released.

Two such books hit the stands recently, David Small's National Book Award-nominated (but kids only!) Stitches and the Ken Dahl's Monsters. The good news is that both books deserve at least some, if not all, of the positive attention they've been getting.

Stitches is about author David Small's peculiar and rather bleak childhood. The child of emotionally distant and withdrawn parents, Small found himself constantly trying to maneuver around them, avoiding their wrath, particularly that of his mother, who seemed to capable of deep, dark and ugly mood swings. A sickly child, Small was frequently subjected to x-rays by his radiologist dad, which, in his teen years resulted in his contracting throat cancer. The amazing part is that Small's parents let it go untreated for three and a half years and, worse still, kept the nature of his illness a secret from him.

It's his parents' seeming indifference to his plight, both physical and mental, that mark this book and give it its heft. Small's later anger at his folks when he discovers their duplicity as a teen is palpable, and it's clear a lot of that anger still lingers in sequences where his mom goes on a shopping spree, while he gets steadily more ill.

If there's a problem with the book it's that Small pulls up too many loose threads. Issues, like his awkward relationship with his father, are brought up but never explored satisfactorily. His older brother surely must have had some influence on his upbringing, but he's barely a supporting character. He hints at being bullied by classmates, at the demons that hounded his mother, and even his maternal grandmother, but he keeps a certain distance from direct revelation. That does give the book a sense of mystery, of terrible family secrets best left unexplored, but it also can make for a frustrating reading experience .

But if the book feels unfocused at times it remains a captivating read nevertheless. Small has a great visual acuity no doubt honed by his many years as a children's book illustrator, and he is able to offer a number of stunning sequences, particularly when attempting to express his own fragile emotional state at the time. At one point, for example, in attempting to explain how art provided a respite from the outside world, Small draws himself literally diving into a piece of paper. In another he shows his final emotional release with a caring therapist by portraying a rainstorm slowly, over several pages, as it moves across the neighborhood.

It's sequences like those, and many others, that make Stitches ultimately work and worth recommending. Small's story is certainly shocking and moving enough to be draw in an initial crowd, but it's his telling that makes you want to stick around and listen till the end.

Ken Dahl's big trauma, meanwhile, happened to him when he was an adult. Monsters, you see, is not about parental problems or awkward adolescence but about sexually transmitted diseases. Herpes to be specific.

As topics go, it's certainly about as intimate and personal as you can get. Few people would want to go public with such a revelation, let alone talk about it over dinner with friends. But Dahl proves to be a fearless and funny storyteller and Monsters makes for a hugely entertaining read.

The book starts by asking the sentence "Imagine never kissing anyone on the lips again" before segueing to Dahl and his then-girlfriend ensconced in young-couple bliss. Soon, however, said girlfriend starts to have problems "down there." A trip to the doctor reveals it's oral herpes. Worse yet, Dahl probably gave it to her, possibly through the frequent cold sores he contracts.

And it's here that Dahl begins his slow, horrible spiral downward, as his relationship flounders and eventually self-destructs. He tries to remain virtuous, and avoid sexual contact, but the life of a celibate is a tough one (in one of the books best sequences he literally turns into a dog in heat as he watches beautiful women pass by on a park bench). He frustration and self-pity lead him to hooking up with a woman at a party and he conveniently "forgets" to tell her about his little problem. It takes a lot of education, self-flagellation, poor medical choices (one of the concurrent themes of the book is the lack of adequate medical care in America) and frustration before he finally meets a woman willing to see past the disease and accept him. And then there's the final punchline, a bit of delicious irony I wouldn't dream of spoiling.

Dahl balances all these painful, awkward revelations with information about the disease itself (did you know that about 75 percent of people in the U.S. have herpes?). Usually, this sort of dry, "here's the facts" delivery would slow the book to a halt, but Dahl keeps his wits about him and makes such sequences as lively as the more dramatic parts of his story. Anyone looking for ways to discuss large amounts of abstract information in a readable way should closely examine this book.

As with Small, Dahl's visual vocabulary is his main strength. He has a real gift for caricature that serves him well here. Even when he's drawing a party crowd, everyone seems like a unique individual, or goofball as the case may be. He even gives the disease -- which he draws as a spiky little protozoa -- a personality. It chides him, goads him and occasionally completely envelops him, depending upon his state of mind.

Given the nature of its subject matter, Monsters could easily turn into an unreadable self-pity party. But Dahl is too smart -- and funny -- cartoonist than that. It's that sense of humor, and even downright playfulness, that ultimately makes Monsters such a delightful, warm read. And that's certainly something I never thought I'd say about a book about Herpes.