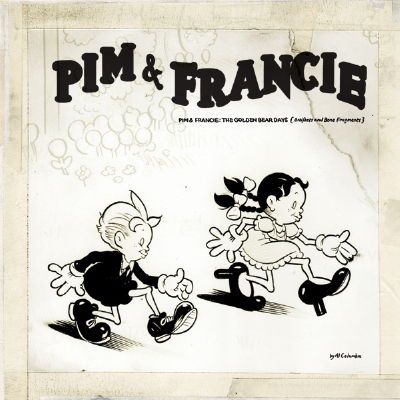

Pim & Francie: The Golden Bear Days

by Al Columbia

Fantagraphics, 240 pages, $28.99

Can an art book have a narrative? What I mean by that is, can book purportedly made up of a series of unrelated images -- or at least, images that don't ipso facto follow a traditional narrative path -- produce one anyway, even if it's unintentional?

That's one of the questions I asked while reading Pim & Francie, Al Columbia's latest (and it should be noted, first ever) book. It's more a collection of unfinished work and ephemera than an outright comic, but it many ways it remains Columbia's most disturbing material yet.

I've written at length about Columbia's work before, so I won't go into too much detail here except to say that he remains one of the finest horrorists (if such a word exists and I may be allowed to use it) working in comics today, far exceeding what is generally held to be the standard of excellence in the genre, via his ability to convey a terrible sense of dread and foreboding.

Unfortunately, he's not a terribly prolific author, as his allegedly perfectionist attitude keeps him from producing comics at anything approaching a reasonable production rate. If Pim and Francie is any indication, it's not a working method that's going to change any time soon.

Pim and Francie is not a comic, at least not at face value. Rather, it's a collection of unfinished comics, a series of half-completed art for a variety of stories started and then stopped over the past god-knows-how-many years, starring the two title characters a puckish boy and girl that originally appeared in the first (and only) two issues of The Biologic Show.

The stories are arranged in haphazard fashion, seemingly out of any real chronological order. Sometimes we get a glimpse of a whole page. Sometimes it's just a panel or two. Sometimes the art is fully inked. Sometimes it's little more than a few rough pencil lines. Some of the pages are ripped and taped back together, an indication, perhaps, of just how frustrated and irritated Columbia gets with regards to his own capabilities.

As for the stories themselves, they're malevolent things, shaped largely from the traditional folk and fairy tales that help make up our culture but minus any "happily ever after" conclusion. An array of dark and murderous forces are constantly after Pim and Francie, be they the leering, cannibalistic Cinnamon Jack, the Goofy-esque Hamburger Harry (aka "The Bloody, Bloody Killer") or even their own Grandma and Grandpa, who, in one of the book's most disturbing sequences come back from the dead as zombies and slowly sneak into the sleeping kids' room, knives in hand.

Pim and Francie rarely come out of these tales in one piece -- even when a story ends abruptly there's the sense that things weren't going to turn out well. When Francie says "I sure hope we don't see the Bloody Bloody Killer" you know that they're going to and that there's little chance of them getting away safely. Columbia's world, as I've said before, is a predatory one, where the young and innocent have very little chance of being anything other than targets. Or supper.

To make all of this material even more disturbing, Columbia for the most part draws in a style that evokes early Disney and Fleischer-era animation. Cute round heads, often wearing Mickey Mouse hats, frolicking in forests with screaming trees or baby birds that have had their eyes gouged out. (Eye gouging seems to be a running theme with Columbia and in one horrific image, Pim and Francie opt to give it a go themselves with a board and some rusty nails.) The characters engage in fixed poses over and over again -- Pim and Francie hold that cover pose for at least a third if not more of the pages in the book. If I were a psychologist (and I'm not), I'd say it suggests a degree of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

As disjointed and narratively frustrating as Pim and Francie can be at times, it remains a stunning and haunting work that preys on your mind long after you've finished it. The successive wave upon wave of unsettling imagery builds upon subsequent page to suggest a world of constant pain and surreal terror, where hiding places are few and far between. Sure, the two lead moppets manage to pop back up none the worse for wear within a page or two, but that's only so they can face another set of existential horrors (or, in some cases, turn on each other).

The sheer level of craftsmanship and imagination on display makes this a book well worth reading for those who can bear its mordant message. And while part of me would no doubt prefer to have these stories in their original, sequential form, I'll take what I can get. Who knows when I'll see something like this again.