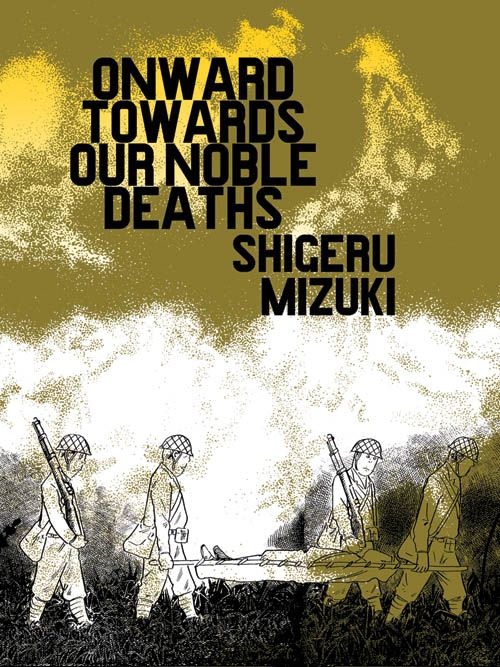

Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths

by Shigeru Mizuki

Drawn and Quarterly, 368 pages, $24.95.

Disclaimer: At the request of the publisher, I wrote a letter of recommendation when they were applying for a grant from a nonprofit organization to aid in the publication and promotion of this book.

Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths is nothing less than a spit in the face of militarism, war and feudal attitudes. It is an angry book, but it doesn't shriek its indignation, though the temptation certainly seems to be there. There are few histrionics on display or scenes of outright, explicit condemnation. Rather, the book is content to let the general inhumanity on display speak for itself.

Shigeru Mizuki is not a name well known to Western readers. In fact, this is apparently the first book by him to ever reach these shores, at least in English. In his native country, however, he is beloved enough that his characters and images (and even a bronze statue of the cartoonist) dot the streets of his hometown. Indeed judging by what people both in this book and across the Interwebs have to say about him it seems perhaps only giants like Osamu Tezuka are more well known and honored.

Onward doesn't resemble the characters Mizuki is best known for -- the yokai (i.e. folklore monsters) and other creatures that make up his most famous work, Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro. Instead the book offers a somewhat fictionalized account of the author's time spent in what would eventually become Papua New Guinea during the height of World War II (an experience that cost Mizuki one of his arms). Here, a handful of soldiers are given the task of holding the island back from American troops, a no-win situation that might seem more acceptable if it weren't for the fact thousands of Japanese troops are being held in reserve only miles away.

At first the soldiers only seem at prey to the elements, wild animals and their own stupidity (one soldier attempts to grab a fish with his mouth and ends up choking on it). As the situation worsens, however, and the enemy draws near they are forced to make a suicide charge by their commanding officer. Mizuki makes clear this is an unwise military strategy; the captain stresses that gurilla tactics would be better, but the commanding officer is green, arrogant and vainglorious, his head full of fairy tales about samurai bravely sacrificing themselves for the greater good.

Indeed, sacrifice is frequently requested and expected by the officers, but with little rhyme, reason or reward. Mizuki portrays Japanese army life as one of not just hardship but outright abuse. The lower ranks and rookies are routinely beaten and kicked because their low status ranks them as little more than cattle. The suicide charge just underscores how dispensable they truly are. And when it all goes wrong and some soldiers make the mistake of surviving, measures are taken to ensure that dignity and decorum is preserved, even if it means a further cost of human life (or, perhaps by extension, winning the war).

Though the backgrounds are heavily detailed almost to the point of pure photorealism (a sequence of American bombs falling and wrecking havoc is one of the most stunning visual sequences in the book) the characters themselves are barely sketched out -- little more than basic cartoon shapes actually. Ostensibly, this shouldn't be too much of a problem, and indeed the juxtaposition between the cartoonish cast and the realistic setting leads to some disturbing moments, particularly in the more violent episodes, and it allows for Mizuki to indulge in the occasional bit of slapstick humor to keep things from getting too dour.

But Onward has a large cast, and despite the character guide offered in the beginning, it's very hard to tell the soldiers apart, with only shape of their head, body size and a few other distinguishing characteristics, like glasses, to help the reader out. With one or two exceptions, no one in the cast really distinguishes themselves either. We don't really get to know these men, their past lives and their hopes and fears the way we do in a more traditional war story. While this does help underscore the expendable nature of the grunt soliders, it also has the unfortunate effect of distancing the reader somewhat from the proceedings.

If Onward resembles any Western comic, it is almost certainly It Was the War of the Trenches, Jacques Tardi's searing indictment of World War I. Like that book, it takes the grunt soldier's point of view to condemn those in the higher ranks for their general savagery and forcing the men they claim to be responsible to sacrifice the lives of themselves and those around them for selfish, petty reasons. Of the two, I think Trenches is the better book, if only because you become more involved in the rank and file's inner thoughts, but that's not to suggest Onward suffers grievously in comparison.

I've criticized Drawn and Quarterly in the past for skimping on background and biographical information on their gekiga line. I'm happy to say that's not the case here. A including a nice introduction by Fredrick Schodt, some helpful footnotes, an afterword by Mizuki and an interview with the author. All of these things add to a deeper appreciation of both the book and Mizuki's talents and I hope D&Q continues to contribute more text pieces like these in their future manga releases.

For those fascinated by military history and WWII in particular, Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths provides a penetrating look at the suffering and absurd injustice inflicted on Japanese soldiers by their very own army. Some, I suspect, might balk at the author's portrayal of average grunts, given the atrocity of Japanese war crimes like the Bataan Death March. While he doesn't directly address these injustices, there can be little doubt after reading the book as to where Mizuki's sympathies lie. You know who's side he's on.