In order to find a home for Mickey Mouse on the comics page, cartoonist Floyd Gottfredson and his cadre of artists had to change things around a bit. The freewheeling, anarchic, carefree, gag-filled attitude of the cartoons was slowly replaced with fast-paced adventures stories, and while Mickey's basic nature didn't change much from the cartoons to the newspaper page, he did become tougher, pluckier and wilier. Gottfredson never abandoned the slapstick antics of the cartoons, but instead integrated it into the daily strip. Never the focal point, instead it was one of many elements used to keep readers engaged.

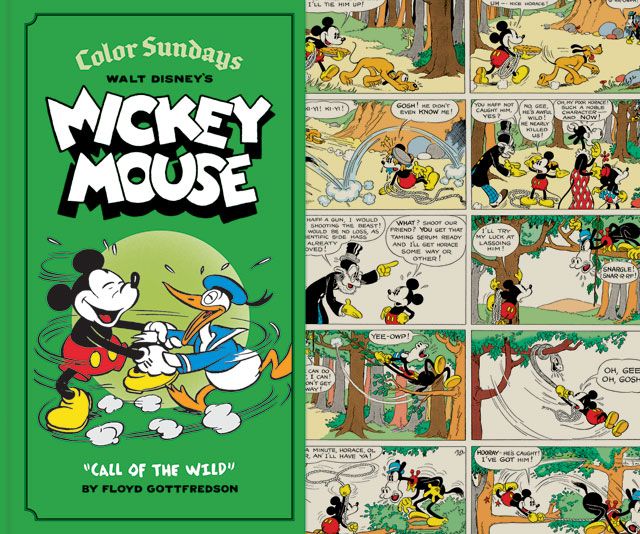

But that was the daily strip. The Sunday strips were a different matter altogether. As editor David Gerstein notes in his introduction to "Call of the Wild," the first collection of Sunday Mickey Mouse comics, the extra space that the Sunday color section allowed encouraged Gottfredson to lighten up a bit. Perhaps he was also discouraged from doing lengthy serial adventures because he initially felt that readers wouldn't be able to follow the stories on a once-a-week basis. Whatever the reason, the strips contained in this first volume, which span 1932 to 1935, are played for laughs far more than the dailies do.

In fact, the earliest strips in the book adhere close to the look and feel of the black and white animated cartoons, with lots of destruction caused by Pluto, Mickey (usually inadvertently) or other outside forces in the best Keystone Cop manner. And regardless of how bad Mickey behaves or much pain or damage is inflicted, the final panel always shows Mickey and/or Minnie smiling and happy. No doubt this was a boon to those suffering during the Great Depression, but to my modern eyes, their devil-may-care attitude is at least a bit disconcerting. Certainly I would be a wee bit upset if a runaway lawn mower destroyed my home or I got stung by myriad bees.

By 1933, however, things begin to change. While not abandoning the gags entirely, Gottfredson slowly starts to add more serial, cliffhanger-styled stories into the mix. Still, compared to what was going on in the dailies around the same time, with Mickey thwarting would-be dictators or exposing small town corruption, these adventures seem much more benign by comparison. The evil cattle rustler Wolf Barker just doesn't match up in threat and temperament to Peg Leg Pete or Eli Squinch.

There's also a feeling of deja vu with the Sundays as Gottfredson starts reusing familiar plots. If the dailies had Mickey adopting a baby elephant, in the Sundays he deals with a boxing kangaroo. And if he had Pluto dog-racing at one point to save a friend's home, he has the kangaroo box a gorilla, because why not? And Mickey and the gang went on a camping trip in 1931, he sees no problem with having them do so again, though this time the nefarious gypsies have been replaced by an eccentric scientist who inadvertently turns poor Horace Horsecollar into a primal beast.

But as time passes, you can sense Gottfredson getting a better feel for the unique rhythms of the Sunday strips. Even the later gag strips are better honed and timed, and thus much funnier (the introduction of Donald Duck and two havoc-causing nephews doesn't hurt matters either). What I really took away from this book, however, was Gottfredson's considerable (and very nuanced) compositional and storytelling skills. It's interesting how he is able to set up an action sequence, whether for comedic purposes or just for straight-out thrills without fiddling too much with the layout. There are no "dynamic panels" here that typify so many superhero comics (and, let's be fair, most contemporary shonen and shojo manga). He's not a fan of tight close-ups or tricky camera angles either, preferring to adhere to a basic grid and frame his sequences in a mid-level, direct shot, occasionally perhaps pulling back a bit to provide a bit of background or context (which, by the way, is not to suggest that it is a simply drawn strip. The opposite is true in fact, Gottfredson's Mickey abounds with carefully delineated detail). It sounds like the formula for dull comics, but in fact the opposite is true. The strips are just as much fun, if not more so, than your average mainstream read.

As with previous volumes, Fantagraphics, Gerstein and company do their usual stellar production job here. The reworked color is exquisite, and the copious notes and back matter provide some much valued historical context and analysis.

So if "Call of the Wild" doesn't quite reach the level of inspiration found, say, in Vol. 3 and 4 of the daily books (though a story where Mickey visits a land of giants comes awful close) it's still an entertaining read and still a thrill to see what Gottfredson work out and then master this longer styled-format. Disney fans – or just fans of solid, entertaining comics in general – won't be disappointed.

Walt Disney's Mickey Mouse Color Sundays Vol. 1: Call of the Wild by Floyd Gottfredson, edited by David Gerstein and Gary Groth, Fantagraphics Books, 280 pages, $29.99