The first volume of March, released this week by Top Shelf Productions,just oozes respectability. Its author and protagonist is a well-known and well-respected figure, no less than a venerated U.S. congressman. It's about an important subject – race relations – and set in a iconic and turbulent time period – the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. It's the kind of book that both the comics industry and the mainstream media like to trip over themselves in holding aloft as an example of the sort of general interest, literate work that would not only appeal to a non-comics reading public, but can be shown as an example of how the medium is capable of more than mere spandex fisticuffs.

In other words, I absolutely dreaded having to read the thing.

It's not that I think that comics only work best only when they recognize their low-gutter, high-slapstick, overwrought melodrama origins or that cartoonists shouldn't aspire to tackle complex, serious issues. It's more that these sorts of works – biographical dramas where the central character happens to be caught in the midst of a major historical event – tend to simply not be very good, a few notable exceptions aside. All too often it seems as though the authors make the fatal mistake of assuming the subject matter itself is enough to carry the work forward and neglect to focus on things like crafting sharp dialogue, compelling page compositions or an interesting – or even comprehensible – plot. The end result is a lot of boring books with noble intentions.

Thankfully, that's not the case with March. While the comic stays well within its basic, Bildungsroman structure, it's an engaging, well-crafted read nevertheless.

No doubt that's largely due to the the talents of the artist Nate Powell. While he's been making comics for a while, Powell caught most people's attention (including mine) with his 2008 graphic novel Swallow Me Whole, a tale of two mentally ill siblings. And while I wasn't as enthused by his major follow-up book, Any Empire, he remains a cartoonist always worth checking out.

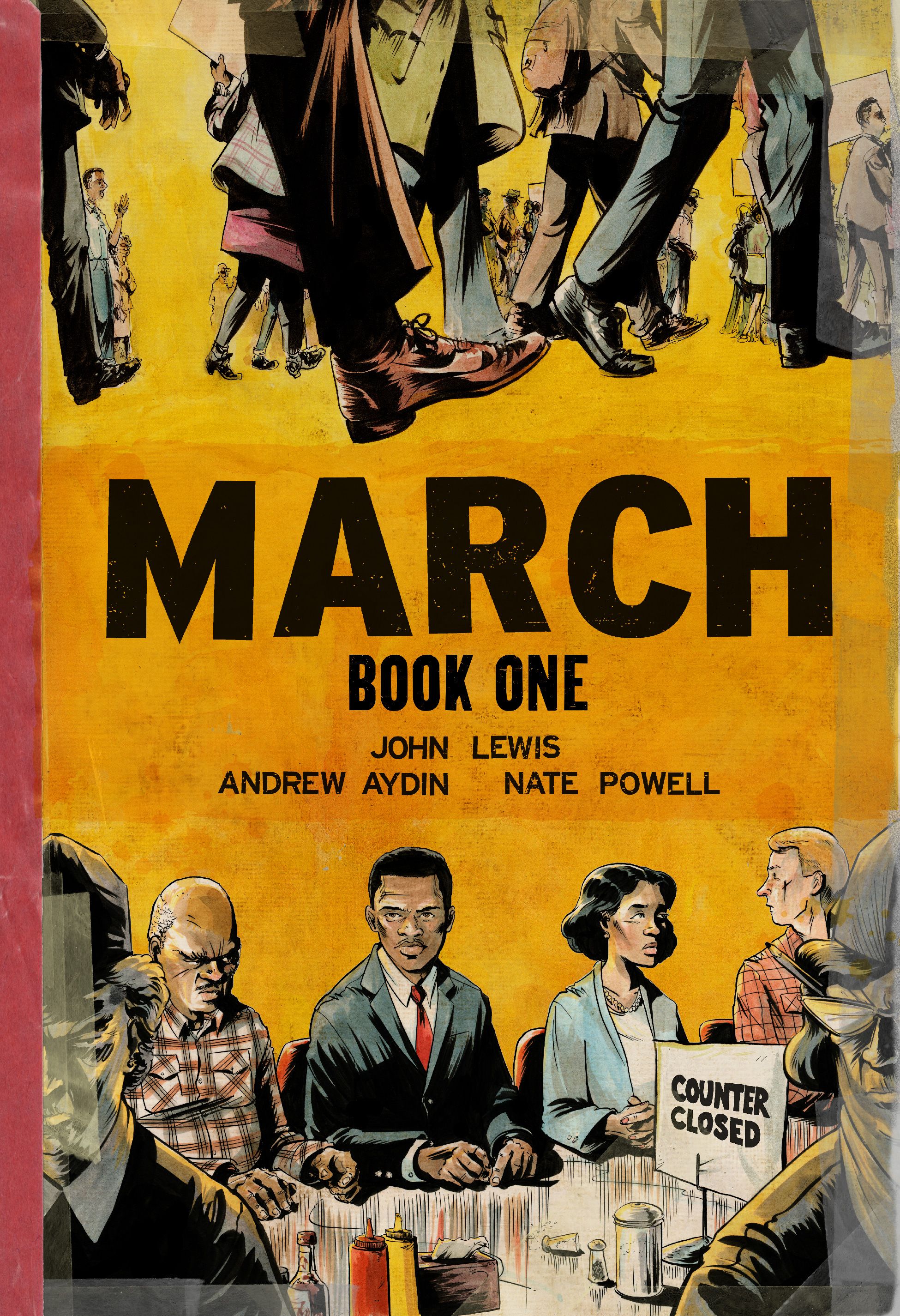

While the story itself is told in rather straightforward fashion – Rep. John Lewis relates his childhood, spiritual and social awakening in the American South, and how he became active in the civil rights movement, eventually taking part in various lunch counter sit-ins – Powell brings his artistic skills to the fore to effectively dramatize the congressman's story. For the most part avoiding a traditional grid structure, he frequently opts for long, horizontal panels, stacked on top of each other in occasionally askew or overlapping fashion. He shifts between tight, dramatic close-ups of faces, hands and feet and sprawling downtown vistas, thronged with people.

But his real skill here is in as an inker. Powell fills his pages with some really lovely black and gray washes, except when he chooses instead to make ample use of open white space, and lets his panels seem like they're simply floating on the page. There's a sequence where a young Lewis and his uncle are driving north, and when Powell shifts from the country to the city he switches from a minimal, quiet sequence of pages to a lavish, lush, full-page bleed of downtown Buffalo, all the better to to covey the grandeur that even a small city would hold to a country boy like Lewis.

The biggest strike against the book is its awkward framing sequence. March opens with, and occasionally comes back to, Rep. Lewis preparing for Barack Obama's 2008 inauguration, and talking to some young constituents and their mother about his past, as they ask some weirdly phrased questions ("What did you do after high school?" "How did you go to college?"). It's an intrusive, unnecessary device that snaps the reader out of Lewis' compelling tale, and the book would have been improved significantly if it had been removed early on.

But perhaps the worst thing about March is that it ends too soon. Just as the narrative is picking up steam, with the sit-ins succeeding but suggesting bigger battles in the near future, it comes to a dead halt. It's a odd, unsatisfying conclusion. Rather than feeling like a satisfactory cliffhanger I felt like I was unduly interrupted in the middle of a really good story.

Still, all that aside, Rep. Lewis is a born raconteur (an important quality for any preacher) and he found able partners in Powell and his co-writer (and staff aide) Andrew Aydin. Many will likely praise or highlight the graphic novel solely because of what it's about than how it goes about its business. The good news is that the craft on display in March is as noteworthy as the subject matter.