by Yuichi Yokoyama

Picturebox, 320 pages, $24.95.

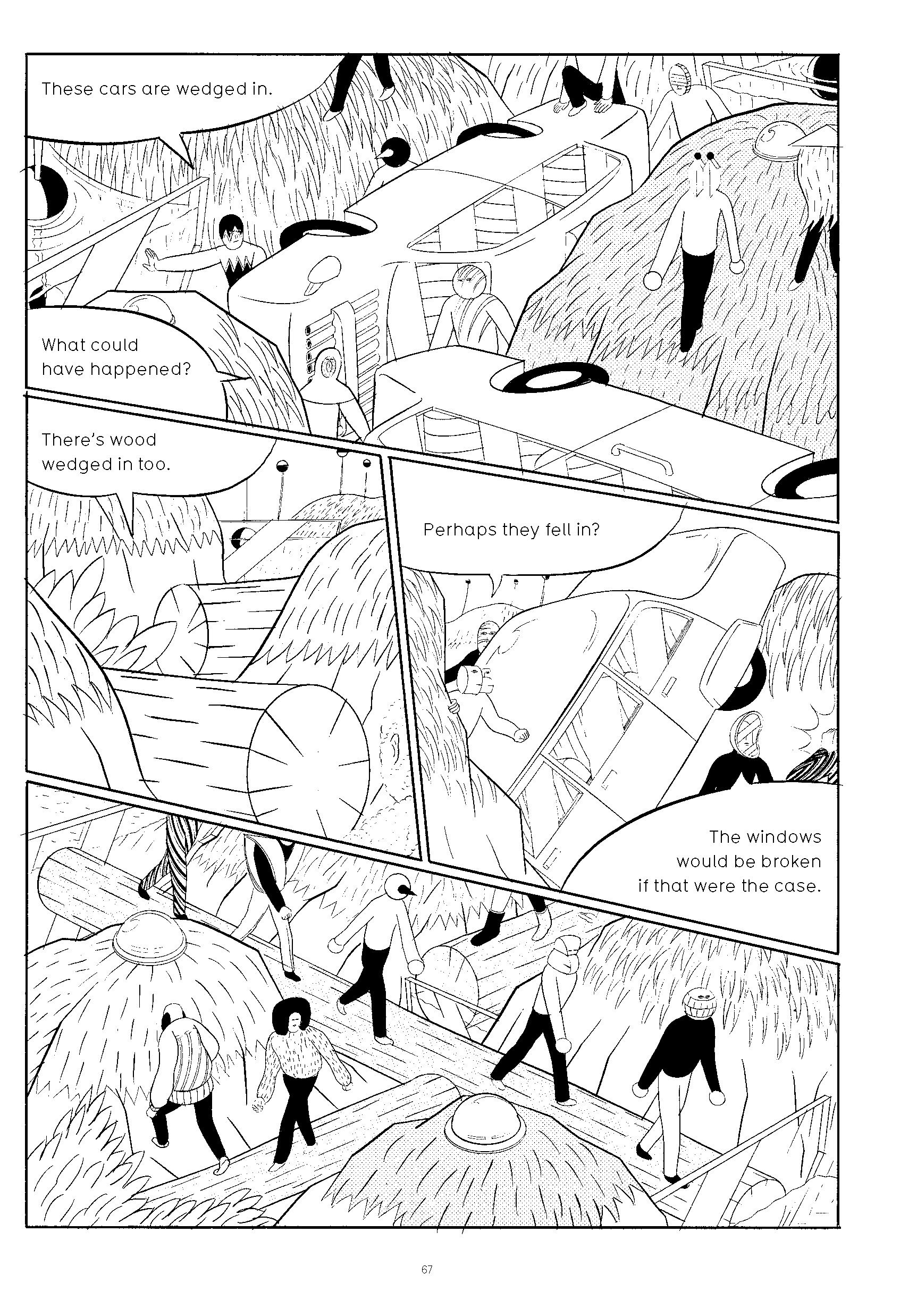

It might seem odd at first glance to describe Yuichi Yokoyama's work as dynamic, given his minimalist, antiseptic style that edges ever so closely to outright abstraction without ever crossing the line. Yet a close inspection of his work, particularly his latest book, Garden, shows what an utterly apt adjective it is. Nothing of significance ever happens in Yokoyama's world, at least not in the sense we think of it when talking about narrative. There's precious little plot per se, no threats or crisis, and no character development to speak of. Yet everything is in constant motion, in constant flux, if not already transforming then ready to be transformed into something else or at least be moved about. No one stands still in Garden, and their actions are depicting in tight close ups, off-kilter worm's-eye-views or panoramic vistas. He's Jack Kirby without the bombast or violence.

Garden starts out simply enough: a large group of people (or what passes for people in Yokoyama's world) find a break in a wall in what is described as a "very good" garden and walk in and start to explore it.

And that's about it. The build-up comes from the increasingly surreal and complex creations the group stumbles upon. Rivers made of rubber balls and tree planters made out of cars give way to rooms filled with soap bubbles, libraires that contain books that are ten feet tall or a mile wide, and a town set entirely on casters. Who made these objects and what, if any, functional purpose they serve is unimportant. Destinations and revelations are unimportant in Yokoyama's work and honestly would only spoil the mystery. The discoveries made along the journey is all that matters.

As with Yokoyama's previous works, New Engineering and Travel, Garden explores Yokoyama's fascination with not only motion but architecture and landscape, and, more significantly, how mankind and technology can often blend the two in strange and unexpected ways.

Yokoyama also has an obsession with depicting things at odd angles or through strange viewpoints. In Travel it was exemplified by a lengthy sequence that showed the way rain water moved down a window and was reflected on a passenger's face. In Garden, there are breathtaking sequences involving photos of the cast being projected on giant walls and water surfaces, a seemingly endless hall of mirrors and watching shapes twist and distort as their images are filtered through the afore-mentioned soap bubbles.

Another idiosyncratic aspect of Yokoyama's comics is that he seems unable or at the very least unwilling to let his characters resemble normal humans. They normally feature instead some sort of bizarre or elaborate headgear. One character has a baseball for a head. Another's head consists of the nose of an airplane. Still anothers' seems to be a honeycomb and so on. Throughout the book, there's a character who constantly takes pictures of the surroundings (an act which does aid have some muted significance at the end), but at about the halfway point I began to wonder if maybe he wasn't really taking picctures, but that his head design was simply that of a guy taking pictures if you see what I mean. Such are the directions your thought processes take when reading a book of this nature.

This is the longest of Yokoyama's works that's been translated in English so far and also the one with the most amount of dialogue (only a few stories from New Engineering had any dialogue). It's purely functional, however, as the characters merely comment to each other about the objects they encounter, uttering statements like "What is this place?" and "Let's go in here." But remember: the characters are not there to show personality or depth or growth. They are there to explore, observe and report.

It's become a cliche to describe a cartoonist as original, but Yokoyama truly stands apart from his peers, both here and in his native country of Japan. At first glance Garden may seem foreboding, stand-offish or perhaps even downright dull. It's anything but however. In fact, I wish mainstream comics had a tenth of the imagination and energy Yokoyama exhibits here. Despite it's placid appearance, Garden is a one heck of a thrilling book.

Disclaimer: Picturebox publisher Dan Nadel also happens to be one of the editors at the new Comics Journal website, where I am an occasional contributor.