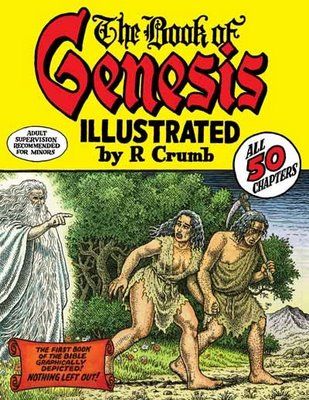

The Book of Genesis Illustrated

by Robert Crumb

WW Norton, 224 pages $24.95.

It's a pretty safe bet that whatever book you pictured in your feverish little brain when you heard the phrase "Robert Crumb adapts Genesis" will never match, or perhaps even compare to, the actual product. When surrounded by as much anticipation and hype as this book has been, (virtually every blogger on the block has declared this the de facto "book of the year," or at least the "book they're most looking forward to") there is bound to be some disappointment.

That's especially true if what you were expecting was anything more than the all-too-literal, note-for note interpretation that Crumb has ultimately produced (indeed, except for a phrase here and there, he seems to have left the sacred text intact). If you were hoping to see some sort of sly, satirical take on the Bible, sorry, but that's not here. If you were expecting googly eyes and big feet, go elsewhere. There is the occasional bit of flop sweat, but otherwise, Crumb keeps his cartoony vibe in check. There's not so much as an ounce of irony to be found.

That even extends to depicting the level of sex and brutal violence that these stories are so well known for. Surprisingly, for the guy who created the incestuous "Joe Blow," he stays well within an R rating, avoiding any explicit, full-on depictions of genitalia or coitus. He's not afraid to show naked bodies entwined or swords splitting heads, but he refuses to become too explicit, even when the text calls for it -- his depiction of Onan masturbating is shown from the side, with no spurting penis to be found. I suspect that Crumb's reasons for this have less to do with an attempt to cater to the religious audience or even the mainstream market place (they're going to be turned off by the blood and breasts anyway) than Crumb's refusal to pander. The overall tone here is one of respect, not towards the Christian or Jewish religion, but instead to the people and cultures and civilizations that inspired these stories.

The result a rich, introspective, at times frustrating, but ultimately rewarding book, that warrants repeated readings and forces the reader to re-examine their take on the first book of the Bible, as well as their attitude towards the artist himself.

There's a danger here in adopting such a straightforward tone. The book could have easily, without the author's intent, slipped toward the reverential, or ended up as some sort of stiff, Classics Illustrated-style adaptation that added nothing to the original work. And indeed some of the early "Creation" chapters have this "Picture Stories from the Bible" feel. But Crumb's ultimately too good an illustrator and storyteller for any of that nonsense. Even though he holds himself strictly to a mostly nine-panel grid and hardly ever breaks out into one of those full-page or even half-page spreads he's so good at, Genesis remains a compelling, dramatic account.

What Crumb ultimately seems to draw Crumb to these stories is the various inherent dichotomies of the text -- chaos versus order, barbarism versus civilization, secular versus spiritual and, in particular, men versus women. Anyone who's read any version of Genesis knows that despite being a patriarchal text, the women of Genesis play a large and important role. Crumb highlights and emphasizes this role through his art. It may surprise and even frustrate those who continually write Crumb off as a misogynist, but his Genesis offers a decidedly feminist spin. His sympathy is clearly with Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel and the other wives in this saga (although he still portrays them in that gap-toothed, voluptuous, taut nippled style he's so clearly enamored of) .

Indeed, in his lengthy (and very insightful) notes, Crumb, in trying to explain some odd or contradictory passages, suggests that many of the notable women in Genesis, like Sarah, might have been priestesses, or come from matriarchal societies. Indeed, he posits that many of the Genesis stories could be myths from a matriarchal society rewritten and reshaped for a new, patriarchal paradigm.

Whether or not that is the case, I do think that these women's stories underline the limited but important role women played in these early societies. My wife has a saying that she likes to use when she's feeling rather irate or put-upon by the rest of the household: "If Mama ain't happy, ain't nobody happy." That's a phrase that could easily see Sarah or Rebekah sputtering out in rage. Reduced to the role of childbearer, their sole importance centered on providing a male heir, it doesn't seem that surprising that these omwen would exert their influence whenever possible, as Sarah does in forcing the banishment of her handmaid Haggar, or in Rachel and her sister Leah's squabbles over their husband, Jacob.

As I suggested before, there's little interplay between the images and text. What the narration describes is usually what you see. If there's any subversion to be found in this book, however, it's in the characters body posture or facial expressions. Crumb is very subtle here, but his it's the minor details that make this book as striking as it ultimately is. If you get a chance to look at the book, notice the eyes of the character, what they're looking at and how. Note the disgust on Joseph's expression when he says "I'm not God am I?" Or how Dinah reacts when she's led out of the House of Shechem after her brothers have slaughtered everyone inside. Or the terror on Rebekah's face when she fears Esau may try to slay Jacob (and Isaac's henpecked look in the following panel, as Rebekah rails at him). It's in moments like these that Crumb is able to convey these character's inner humanity. They no longer seem like unrecognizable archetypes, but real flesh-and blood humans.

The story I found myself the most drawn to is that of Joseph, the boy with the coat of many colors, who is sold into slavery by his brothers only to rise above them all through his cleverness and guile. I found myself surprisingly moved by Crumb's depiction of this lost soul. His anger and pain upon rediscovering his treacherous brothers feels real and honest. The world Crumb portrays in Genesis seems like a harsh and unforgiving one, full of inky darkness and sweat and flesh, where brothers battle brothers, fathers battle sons and life, especially female life, isn't worth much unless you have cattle, grain and water and lots of people to do your bidding. Still, it is not a place devoid of nobility or honor, or perhaps even love, though that last one seems to perhaps the hardest to find.

This is a book that is going to frustrate and annoy many. It frustrated me at times. Crumb is striving for something much subtler here than he's attempted before and coming to it with a certain set of expectations is only going to lead to disappointment. Many critics will no doubt decry the book for going with obvious choices, like making God a big white guy with a long, flowing beard.

But Crumb doesn't seem as interested in completely rejiggering our perception of the text or playing against traditional norms as much as he is in skewing our perspective ever so slightly. There are insights to be gained in this adaptation. But it's all in the eyes.