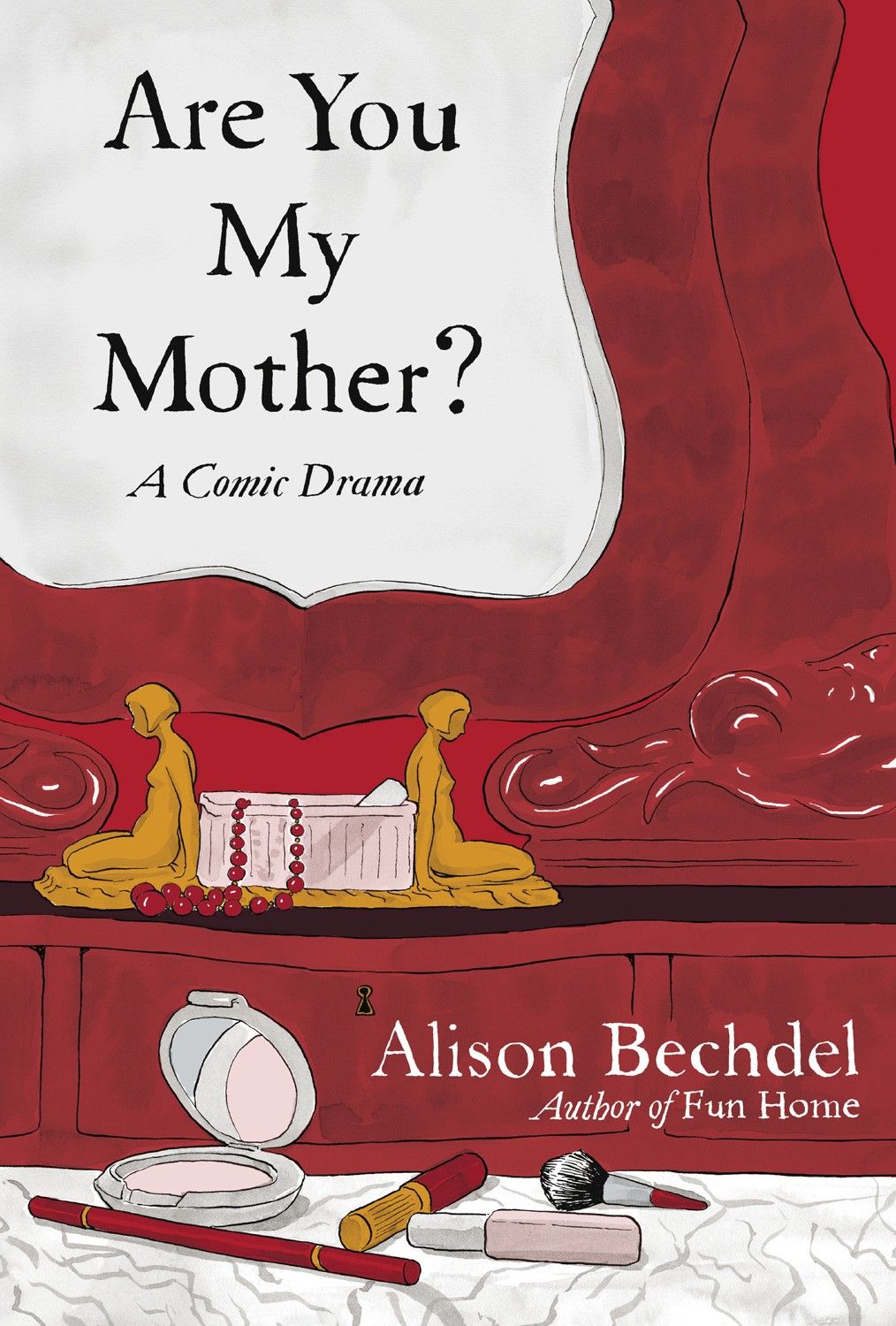

Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama

Houghton Mifflin, $22.

by Leela Corman

Schocken Books, $24.95

Are You My Mother is one tough nut of a book. Dense, analytical, filled with allusions to classic literature and psychoanalysis, it consciously resists easy interpretation or tried and true conventions. It's an adventurous, thoughtful and fascinating book -- I have no qualms about recommending it -- but it's chilly and distancing, and I suspect it will frustrate many readers, even those who cherished author Alison Bechdel's previous book Fun Home.

Mother is in many ways a direct sequel to Fun Home, Bechdel's highly touted and incredibly successful (at least in comic book terms) memoir of her father. It's not impossible to come to Mother never having read any of Bechdel's previous work, but the book refers directly to issues raised in Fun Home, so being acquainted will undoubtedly help.

Even the title Are You My Mother? suggests the book will serve as a companion of Fun Home: First you learned about one parent, now you learn about the other. And certainly Bechdel's mother, and the mother-daughter relationship, is one of the central themes of the graphic novel. Ultimately, however, the book is not really about that. Or, at least, it's not only about that, because Bechdel spends a sizable chunk of the book discussing her relationships with her therapists, some of her failed romances and the writings of psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, as well as that of Virginia Woolf, Adrienne Rich and even Stephen Sondheim.

As a result, it's difficult to get a handle on Bechdel's mother. In the book she comes off as incredibly intelligent and blessed with a keen wit and critical insight, but also distant, seeming to constantly keep her daughter -- and by extension the reader -- at arm's length, declaring at age seven, for example, that Bechdel is too old to be kissed good night anymore. She obviously loves her child (why else even give your acquiescence to a book like this) but she seems unwilling or unable to express that affection directly in a manner that Bechdel seems to so obviously crave.

But if Bechdel's mother seems to be partially hidden behind a curtain, the author is partially to blame for this as well. While by the end of the book we get a sense of what her mother is like as a person, we really know little about her. Her childhood merits only a few pages of discussion, to say nothing of her adolescence or her relationship with Bechdel's father. What were her parents like? Who were the major influences in her life? Why did she choose marriage instead of a career? How does she feel about being married to a man who was not only a closeted homosexual but also verbally abusive? How deep does the bitterness about her not choosing a life of letters run? (I suspect very deep.) Bechdel hints but frustratingly never gets any real answers.

For instance: Bechdel expresses pain and frustration over her mother's reluctance to accept her lesbianism, especially when it comes to her chronicling LGBT culture in her comics, whether it's Fun Home or her decades-long comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. Bechdel seems to chalk this up to issues regarding her father's closeted life and the shame brought on by his exposed affairs. But she also at one point notes that her mom is pro-life, and in another sequence says her mom was raised in a stridently Catholic family. Could her religious upbringing in some way affect her comfort level with her daughter's sexual identity? Bechdel seems to ignore the very possibility.

If Bechdel ignores issues of faith it's because psychiatry and psychotherapy are her religion, at least as presented in this book. Her relationship with her therapists is chronicled in an almost-obsessive fashion (no surprise to learn she has OCD). Bechdel seems to believe the universe has an inherent order, and that if you dig deep enough and hard enough you can get answers to questions like, "Why am I so fucked up?" To that extent, she seems unwilling to acknowledge that memory and dreams can be untrustworthy or vague as if that would suggest that the clues she so desperately seeks will not lead to cohesive answers. Bechdel sees connections everywhere in the book to the point where the appearance of a spider takes on significant meaning. As Freud famously once said, sometimes a cigar is just a cigar and sometimes a spider is nothing more than an odd coincidence.

Unterzakhn, Leela Corman's first major work since her 2002 graphic novel Subway Series, deals with similar issues as Are You My Mother?, namely gender, sexuality and family. But whereas Bechdel's book is all about stimulating the mind, Corman's is all about pulling the heartstrings.

Unterzakhn is the story of Jewish twin sisters growing up on New York City's Lower East Side in the early 1900s. Parents of immigrants, Fanya and Esther form a close alliance against their cruel mother and gentle but absent, and probably alcoholic, father. This relationship begins to deteriorate as Fanya first takes lessons from, and then ends up working for, an obstetrician who performs abortions and attempts to encourage birth control. Esther, meanwhile, finds herself working at a burlesque house/bordello, first simply as a gopher but eventually as a prostitute and then an acclaimed actress.

Neither girl has an easy time of it, and Corman attempts to say something not just about immigrant and Jewish life, but also about the struggles faced in the early 20th century by women who shunned the traditional roles of wives and mothers.

Whereas Mother is high-minded, Unterzakhn is deeply melodramatic, almost to its detriment. While Bechdel takes pains to be nuanced and fair, Corman's cast is writ large, and many characters verge close to stereotype or indulge in it completely (the mother in particular is a ugly monster with few redeeming graces). With the deaths and lost loves and illnesses -- not to mention the whole epic sweep of the story -- at times it feels like D.W. Griffith could have adapted it into a silent vehicle for Lillian Gish.

The book is at its strongest when it deals with the sisters and their sometimes-warm, sometimes-hostile relationship with each other. A flashback in the middle dealing with their father's history and how he came to America provides a bit of background and adds to the theme of upheaval and immigrant struggles, but ultimately is unnecessary, especially given how much of a nonentity he is in the rest of the book.

Despite my criticisms, I admire Are You My Mother? for its willingness to poke at sore wounds, ask tough questions and refuse to pander to the reader, visually or verbally. It's a smart, challenging and yes, engaging read. And yet of the two, Unterzakhn -- for all of its bathos -- might be the more pleasurable comic.