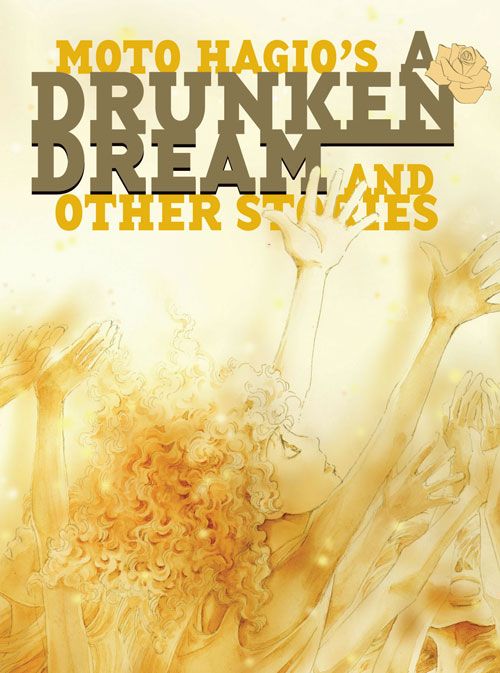

A Drunken Dream and Other Stories

by Moto Hagio

Fantagraphics Books, 288 pages, $24.99.

It will be interesting to see what sort of response A Drunken Dream has in the alt-comix community. While I'm have no doubt that more traditional manga fans (especially older manga fans with an interest in the medium's history) will lap it up and ask for more, I'm not as convinced that your average Fantagraphics reader (if there is such a thing, and I acknowledge full well that I might be off the rails here in even thinking such a thing) won't find this to be a little far afield from their purview.

It's quite unlike Sake Jock, for example, Fanta's first entry into the world of manga -- a collection of work by Garo artists that tend to revel in the profane, surreal and occasionally naughty ("Asia's answers to Robert Crumb, Dan Clowes, and Chester Brown!" says the PR copy, knowing no doubt how best to entice intrigued the skeptical Eightball reader).

Dream, on the other hand, has both feet firmly planted in the world of shojo manga. The ten tales that make up this book all consist of overly sincere, heart-on-the-sleeve-style work. There's very little ironic distancing and self-effacing humor here, although it does peep its head out occasionally. Mostly though, that's been ignored in favor of heightened melodrama and earnest heart-tugging. While it avoids the sort of contrived, romantic, situation-comedy type plots that mark a lot of the shojo manga that has been translated into English over the past decade, there can be little doubt that Dream has more in common with Fruits Basket and Boys Over Flowers than Red Colored Elegy or Abandon the Old in Tokyo.

And that's not terribly surprising, considering that Hagio, along with her peers, all but invented the genre. As arguably the most prominent number of Year 24 Group, also known as the Magnificent 49ers (and, it should be noted, not an actual organization) Hagio (along with folks like Keiko Takemiya and Yumiko Oshima) helped revolutionize shojo by dealing with more serious issues and themes (including sexuality) and via their own example encouraged women to start creating their own manga. Don't like most shojo, yaoi or sci-fi manga? Blame Hagio, if only a little.

With the exception of the title story, Dream largely forgoes the sci-fi and boys' love angles (two genres that Hagio is known for, although by no means exclusively) in favor of slightly more realistic stories taken from over four decades of material.

Most of the stories in the book deal with young girls (along with the occasional boy) who don't fit, either within the confines of their family or in society as a whole. "Girl on Porch With Puppy," a sharp-tongued fable (complete with shock ending!) about a tot who likes to commune with nature in the rain, rather than stay indoors with her sensible and extremely judgmental family, typifies this focus.

Indeed, dysfunctional or deeply wounded families seem to be a staple of Hagio's work. "Autumn Journey" concerns a young man who attempts to reunite with the father that abandoned him many years ago. "The Child Who Comes Home" concerns a family attempting to deal with the grief of losing their youngest member.

Apparently it's a theme with very strong autobiographical overtones for Hagio, as she revealed in the interview (reprinted in this book) she did with editor Matt Thorn in Issue #269 of The Comics Journal. It seems the attempt to both be a good daughter and follow her own creative path created a tension that informs the bulk of her work, at least as evidenced by Dream. Even beyond the family issues, societal pressures and the fear of not living up to your potential drives stories like "Marie, Ten Years Later," about a group of college friends who find themselves far afield of where they hoped they would be a decade after graduation.

Hagio draws these stories as if a full symphonic score were playing in the background. Her delicate, razor-thin pen line expertly captures her characters' wide-eyed, open-mouthed anguish effectively. Make no mistake, she wants to wring as much emotion out of you as possible, and readers who have heretofore been suspicious of such manipulation may turn a cold eye over such tales, in spite of Hagio's sumptuous compositions.

The two best stories -- "Iguana Girl" and "Hanshin: Half God" -- are able to convey the sense of loss and longing by tempering them with a bit of comedy and deep sympathy for and understanding of their protagonists. In stories like these, it becomes very clear how and why Hagio has earned the lofty reputation she has.

If you weren't a fan of shojo manga before, if the big, tear-flecked eyes, sun-dazzled backgrounds, romantic longings and go for broke poignancy didn't butter your bread previously, I'm not sure Dream is going to be the book that pulls you over to the strawberry pink and lace-strewn side of the path. I, certainly, am very glad that Fantagraphics made the effort (and judging by the exceptional production values it was a tremendous effort) to get this book out there. I hope I'm wrong and that non-manga readers, or those with select tastes, are willing to go beyond their comfort zone, because despite the occasional lapses into syrupy sentimentalism, and beyond Hagio's historical significance, Drunken Dream will is a book that deserves attention.