by Yoshihiro Tatsumi

Drawn and Quarterly, 840 pages, $29.95.

Several of the initial reviews of this doorstop of a memoir have focused on its more revelatory, historical aspects -- how it takes us back to a time and place we Westerners know little about, namely the birth of the manga industry and the subsequent rise of gekiga.

That's certainly a valid approach to the work. I know that a good part of the book's enjoyment for me hinged on author Yoshihiro Tatsumi's depictions of the intricacies and politics of the then-budding industry, even if I didn't know every single person by name in the story or got all the references.

But what ultimately propelled me through the book and what compels me to recommend it is nothing more or less than its basic bildungsroman qualities. At its heart, A Drifting Life is the simple story of a young man discovering his talent and by extension his place in the world. It's told in as direct and plain a manner as possible, but still full of energy and passion.

If you've read any of Tatsumi's work beforehand, it was most likely one of the three previous collections of short stories that Drawn and Quarterly released -- The Push Man, Abandon the Old in Tokyo and Good-Bye. To call these tales bleak is sort of like saying water is wet. Tatsumi separated himself from the rest of his manga brethren by offering readers glimpses of the downtrodden and doomed, men and women for whom life and society have left little options or hope. They are short, sharp little shocks to the system that at their best remind us of how easy it is to slide to the bottom and how many people may be there to greet us on the way down.

So Drifting's placid and at times downright sunny nature may come as a bit of a surprise. There is little of the despair that marks Tatsumi's other work, and the little that is present has more to do with deadlines and the attempt to create meaningful art than dire poverty or sexual perversion.

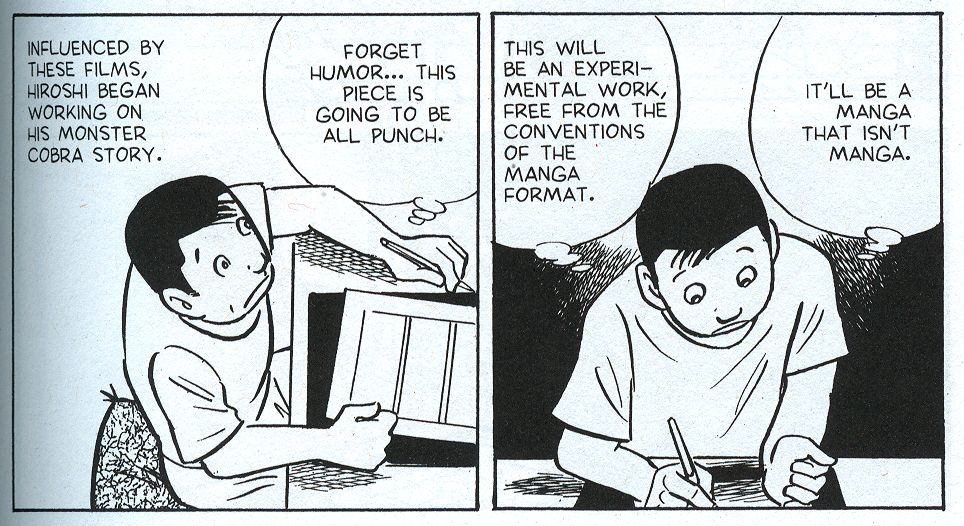

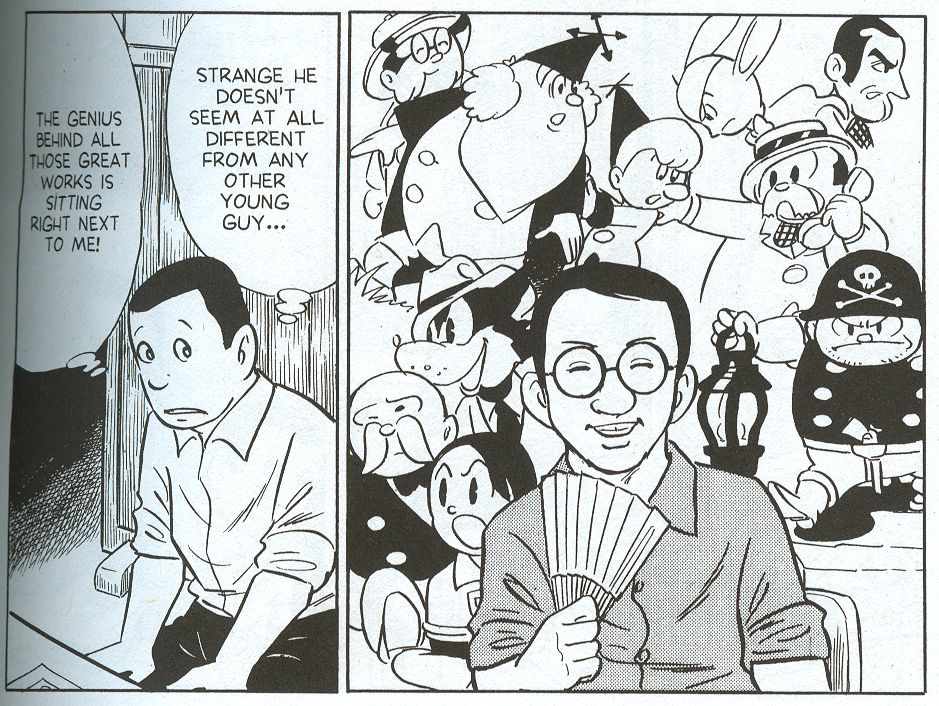

The book opens with the surrender of Japan in 1945 and from there on slowly and methodically chronicles the adventures of Tatsumi stand-in Hiroshi Katsumi. Obsessed with manga, particularly the manga of Osamu Tezuka, Hiroshi attempts to start creating his own, spurred on by his older brother, Okimasa. Met with early success and encouragement in high school, he graduates school to become a full-time manga artist. Eventually discovering like-minded peers and publishers, he attempts to create a type of manga that's edgier and more literary than the cartoony, humorous work of his day, a genre he eventually labels gekiga.

Tatsumi relates his alter-ego's journey to manhood in as methodical a manner as possible. There's a real "and then this happened" quality to the book, as he moves steadily from event to event, seemingly wary to give any one sequence more significance than another.

Yet A Drifting Life is far from dull or monotonousness. Rather it expertly simulates the ebbs and flows of daily life, how one incident leads to the next and the next, and how people move in and out of our line of vision depending upon our own needs and wants at the time.

What more, I appreciated Tatsumi's little details that reveal a good bit about Hiroshi and his milieu, like how his ne'er do-well father immediately tries on his son's new suit jacket, declaring he'll "borrow" it "whenever he needs to look smart," or the sequence where Hiroshi attempts to hire a female model to pose nude for him and his friends in order to improve their draftsmanship. The book is filed with lovely, knowing sequences like those.

Some figures do loom large in the narrative, like Tezuka. His appearance and inital friendship with Hiroshi takes a good deal of space in the early chapters, no doubt to further emphasize how integral the "God of manga's"s work was to second-generation cartoonists like Tatsumi.

If there's one character that looms larger than the others, however, it's Hiroshi's brother, Okimasa. The Charles Crumb to Tatsumi's Robert, Okimasa alternatively acts as mentor (he's the one who introduces Hiroshi to manga), friend, bitter rival and sounding board. He is the instigator who propels Hiroshi to a life of manga, chides him when is work is not up to snuff and is forever driving him on to produce great work, though their definition of great differs widely at times.

The book could have sereioulsy used footnotes. An appendix in the back only serves to translates some of the street signs, letters and newspaper headlines that appear in the book but no attempt is really made to explain who various authors are or the signficance of certain events. It's not an insurmountable problem; it's quite possible to appreciate the book without fully comprehending the underpinnings of every detail. And I can understand why more incisive notes may have been omitted At 800 plus pages, a lengthy series of footnotes would probably have made the book unbindable. Still, it would have been a nice addition. Perhaps someone at Drawn and Quarterly or some intrepid soul on the Internet can put up an online appendix that sheds a little more light on authors like Eiichi Fukui and Masahiko Matsumoto.

Still, as I said, the fact that certain names and events pass by the less acclimated Western reader doesn't make A Drifting Life any less compelling. Tatsumi's story is a familiar one -- that of a man who becomes so enthused by his hobby that he makes it his life's work. What's impressive is how well he manages to capture that giddy rush of discovery, that feeling that not only can you succeed at your work, but you can transform it and yourself, enriching both in the process.