Lovecraft is a hard act to follow, and an even harder one to adapt. “Oh you mean HP Lovecraft, the guy who came up with Cthulhu and all those cute little plush toys.” Yeah, the guy who launched a thousand little cottage industries pumping out VOTE FOR CTHULHU: THE STARS ARE RIGHT bumper stickers and Mythos Hunting Guides and all that stuff. Yeah, him. I do wonder if he’d be tickled or appalled at his legacy and all the eldritch dust-catchers and t-shirts and radio plays.

Well, he’d probably like the radio plays. He’d probably have even approved of the silent film adaptation of THE CALL OF CTHULHU, arguably his single most famous piece of fiction, certainly the one that’s lodged most deeply in the collective consciousness, for good or for ill. The film adaptation ( http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0478988/ for the IMDB page, and it’s streaming on Netflix) gets a solid recommendation from me, and anyone who knows me will tell you that I’m pretty hard to please as this stuff goes. Not because I think Lovecraft’s every word is sacred and perfect. I don’t. My relationship with HPL’s work is problematic, mostly in terms of the execution. I like characters. I like it when characters drive the plot. HPL couldn’t be bothered with that by and large, except when it was an incessant curiosity on the part of the players that made the eldritch secrets of the plot unfurl to their almost unerringly messy conclusions.

So I find HPL’s conceptual work rightly celebrated even if I find his prose nigh-unimpenetrable at times. Which is why I’m often attracted to adaptations of his work, where creators have a desire to stick to the template that HPL laid out, and often there’s some sense of respect for the source material, but it’s filtered through a different sense of aesthetics. HPL-inspired stuff that stars HPL himself? Not so much. Though there was that beautifully-illustrated LOVECRAFT OGN with art by Enrique Breccia that was so wonderful that I simply didn’t care about the story. Though I suppose there’s an interesting vein to mine when talking about Lovecraft as fictional construct rather than historical figure, but that’s for someone else to do.

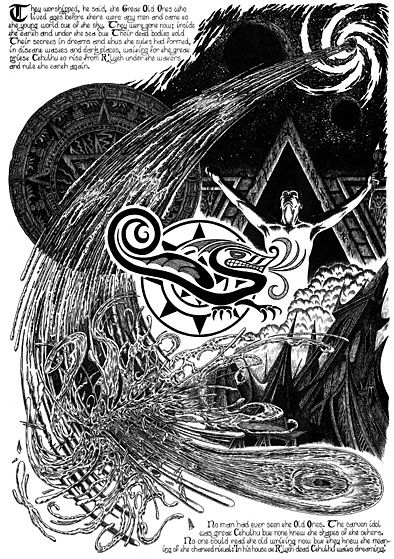

One of the comic adaptations of HPL’s work that’s always stuck with me was John Couthart’s magnificent adaptation of CALL OF CTHULHU, which was as much inspired by the work as it respected the work. Now that’s not the same thing. Inspiration is when the artist is moved to go beyond the letter of the text and take it into a new realm. In that way, it becomes a collaboration, and if you’re lucky, it becomes something as unique as the original work itself. An adaptation can be reverent and respectful, but taken too far, that can become a straitjacket, where the artist is afraid to make a move that somehow steps out of the shadow of the original.

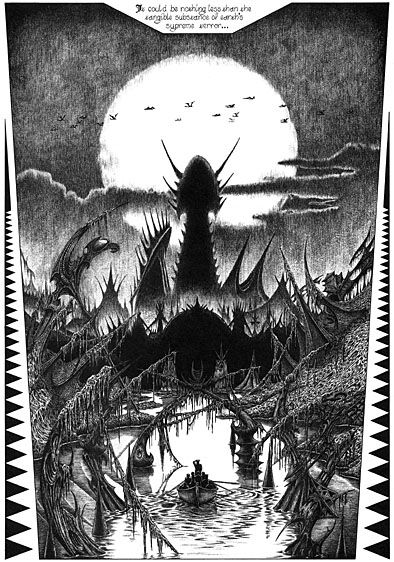

Luckily with Mr. Coulthart’s adaptation, we get to see an artist taking chances and really daring, not just simply literalizing the cosmic horror that HPL at his best served up. Instead of shying away from seeing That Which Must Not Be Seen, Mr. Coulthart shows us everything and dares us to look away. Now, this is not always an approach that pays off. Sometimes it’s just…unseemly or at worst trashy. In Lovecraft adaptations, there’s a fascination with the monster, this incarnation of the cosmic horror that we’re all stewing in. And yes, the monsters are neat, and sometimes they’re even surprising, but the monsters are not the point.

The point is human insignificance in the face of these gaping and half-glimpsed terrors. Very few adaptations get this, and instead fall back on pulp action and exploding creepies from beyond. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. But it’s not Lovecraft.

Mr. Coulthart’s adaptation understands that. Even in the first page, even if there was nothing more than that page, he’s encapsulated the story and better, he’s encapsulated what is best in Lovecraft’s fiction itself: that once the infinite and uncaring horror that sprawls between the stars, once that has been seen, it can not be forgotten, it forever infects the viewers (at least in the stories—we in the outside world merely move on to other entertainments.)

Lucky for us, we have more than that first page. As with the best comics, each page has a life of its own. Some of them more vibrant than others, rejecting a standard storytelling layout and becoming a single whole unto themselves, but still advancing the plot along, still giving us glimpses of what’s driving the characters onward. And, like the globe-spanning-locales of the original tale, Mr. Coulthart anchors the events with his choices in architecture and design, all these tiny details that might go unnoticed but still add to the atmosphere and sense of place.

This isn’t to say that it’s a hidebound historical document that’s more interested in costume drama than fear. It isn’t. There is constant and awe-inspiring horror lurking just beneath the surface, just beneath the scratching ink-lines that at moments feel more like scrimshaw than pen. And this serves further to literally etch these visions into the reader. And to shock in a way that Lovecraft himself might have shied away from in his prose. There is a moment when a group of parish policemen find their way into a swamp to break up a blasphemous and terrible ceremony. Mr. Coulthart goes further than HPL did in his visualizing of the gruesome nature of this cult, making their actions explicit, but not exploitative. That’s a fine line to walk along and often artists end up going too far in an effort to get a reaction out of the audience. I mean, nothing exceeds like excess, right?

That was rhetorical.

I could go on and on about Mr. Coulthart’s brave fusion of underground comics and hints of psychedelic imagery and gorgeous design to tell this story. I could, but maybe it’s better that you get a look at his pages and maybe get inspired to read them for yourself.

I first came across this adaptation in a book called THE STARRY WISDOM: A TRIBUTE TO HP LOVECRAFT, which also features Lovecraftian stories by the likes of Grant Morrison, Alan Moore (the original version of THE COURTYARD which was later adapted into comics form), and even Michael Gira (he of The Swans). I recommend it to all HPL fans, particularly those who want to get their cosmic horror filtered through a more modern sensibility, though I’ll note that many authors take things in directions that I don’t think HPL would have necessarily approved of, particularly in terms of the sensual and the occult.

If you want to see an unflinching (but still quivering and beautiful) vision of Lovecraft’s fictional gift to history, then by all means, track down this adaptation. And do yourself a favor by visiting Mr. Coulthart’s website. You might even recognize some of the work there (such as the surprise that Mr. Coulthart designed the Cleopatra Records logo, for instance), and marvel at the crossroads of his work which spans more than twenty years now and touches on subjects Lovecraftian, hermetic, steampunk, and maybe a name or two that’s already familiar to comics readers.

And thanks to the miracle of the internet, I was able to reach Mr. Coulthart to ask a few questions about the adaptation and how he approached the work.

Matt: Is “comic” the right term for your approach to THE CALL OF CTHULHU? Were you setting out to make a comic book per se?

Coulthart: Strictly speaking I think of those adaptations more as illustrations in sequential form. That might sound like "comic" to most people but my original idea in 1985 was to simply start illustrating Lovecraft properly, having done a few drawings prior to that. My model at the time was going to be Berni Wrightson's illustrations for Frankenstein and the work of Gustave Doré. Before I'd made a start I picked up a copy of the first book in Bryan Talbot's Luther Arkwright series; seeing that made me realise I might be better off trying to do the whole of the first story I'd chosen, The Haunter of the Dark, in comic form instead. Once I'd finished that story the intention was to try something more ambitious so The Call of Cthulhu came next.

Matt: There are moments where you’re very determined to tie the text of the story to what’s going on in a particular page, which gives it the feel of an illustrated novel. But then there’s pages where you cut the text altogether and go “between the words” as it were to really explore the horror of what’s unfolding. Was it difficult to escape the text, the actual words themselves?

Coulthart: Some of it was the old thing of "show, don't tell" but mostly I was trying on the one hand to keep the unique flavour of Lovecraft's prose, and on the other to show more of what was often only implied or hinted at in the narrative. One of the things I liked about story was its international reach; you go from a Rhode Island professor and an art student to sinister Eskimos, New Orleans voodoo ceremonies, the Arabian desert, Norway, New Zealand, and finally the South Pacific. Along the way there's a thread that connects a variety of different religions and beliefs, and it quickly became apparent that I could enjoy myself showing how Cthulhu was represented by a diverse cast of people. Representation is at the heart of the story; it begins with Wilcox's clay tablet and statues of Cthulhu are discovered at key moments.

Matt: Very few pages in your adaptation of THE CALL OF CTHULHU follow a standard grid pattern, becoming progressively unhinged as it were. Some of the pages, and I’m thinking of Old Castro’s story in particular, seem straight out of an illuminated manuscript and not a comic. What inspired those choices?

Coulthart: This is mostly down to my being far more of an illustrator than a comic artist. Illustrating the scenes took precedence over the usual panel-by-panel storytelling that comic readers are used to. This didn't seem to me to be completely unprecedented. Many of the comics I've responded to the most have taken this approach. I liked the frequent emphasis on art over story in Heavy Metal magazine in the 1970s and 80s. Burne Hogarth took a similar approach in 1976 with his Jungle Tales of Tarzan. That aside, the form was dictated by the content to a degree, with the CoC narrative being a collage of different occurrences around the world which eventually piece together. When I started work on the unfinished adaptation of The Dunwich Horror I was using a page grid for that since the story is a lot more straightforward.

Matt: I’ve noticed that many illustrators of Lovecraftian work leap to imagery such as Ernst Haeckl’s (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Haeckel) ART FORMS IN NATURE. That book and aesthetic were a heavy influence on Art Nouveau design, but it seems like there’s precious little dovetailing between Nouveau visuals and Lovecraft in terms of adaptation. You’re one of the few artists I’ve seen who put the two together overtly in terms of design and anchoring things in a time and place. Is it important that HPL’s work stay in time or does it still work in a modern milieu?

Coulthart: I only discovered Haeckel's work after I'd finished those adaptations but even if I'd known of his book I can't imagine how I might easily have applied his pictures to the stories. I think Lovecraft's themes can work well in contemporary terms, he was consciously writing modern horror tales, after all, and his interest in post-Einsteinian physics is certainly relevant today. Some of the stories wouldn't be harmed too much by being brought into the present day although there can be a problem with the way technology has changed people's lives. When you read old detective stories, for example, you find scenes in which an elementary problem or threat would be negated immediately by the presence of a cellphone.

Two things were important when adapting the stories: one was being true to the material which meant treating it seriously on its own terms. This was a deliberate reaction against jokey horror comics. The other was trying to be faithful to the period which meant I was watching a lot of films from the 1930s looking all the time for details. King Kong was a big influence, and where it says "THE END" on the final page the lettering is based on the card at the end of the RKO films

Matt: THE CALL OF CTHULHU was completed in 1988 and was pen and ink. Do you work much in that media any longer or are things largely digital for you now?

Coulthart: I still draw now and then but these days it's mainly preliminary work for digital illustration. After the Lovecraft stories I drew 270 comic pages for David Britton's Lord Horror series, Reverbstorm, and when that ended I felt I'd done all I wanted with detailed, cross-hatched ink work. In the past I've been fairly restless, I've tended to do something in one area then move elsewhere. After the comics I was doing painting for a while then moved to computers. That's bad in career terms since people prefer it when you become established doing one thing but I can't help my impulses.