In 2008, Rick Remender began his Marvel Comics run, spinning dark, epic, action-packed tales with heroes and villains wrestling with the fantastic forces that haunt their world and the personal demons that haunt only them. And while his name quickly rose to the top of many Marvel readers' pull-lists, many fans were unaware that Remender had been telling stories with his own multi-faceted and often conflicted characters almost a decade before his first work at Marvel. Creator-owned comics are in his blood, and after launching several new titles at Image Comics, Remender decided that for the time being, he is focusing strictly on projects he and his creative partners own outright.

RELATED: Rick Remender Taking a Break from Marvel Comics After 8 Years

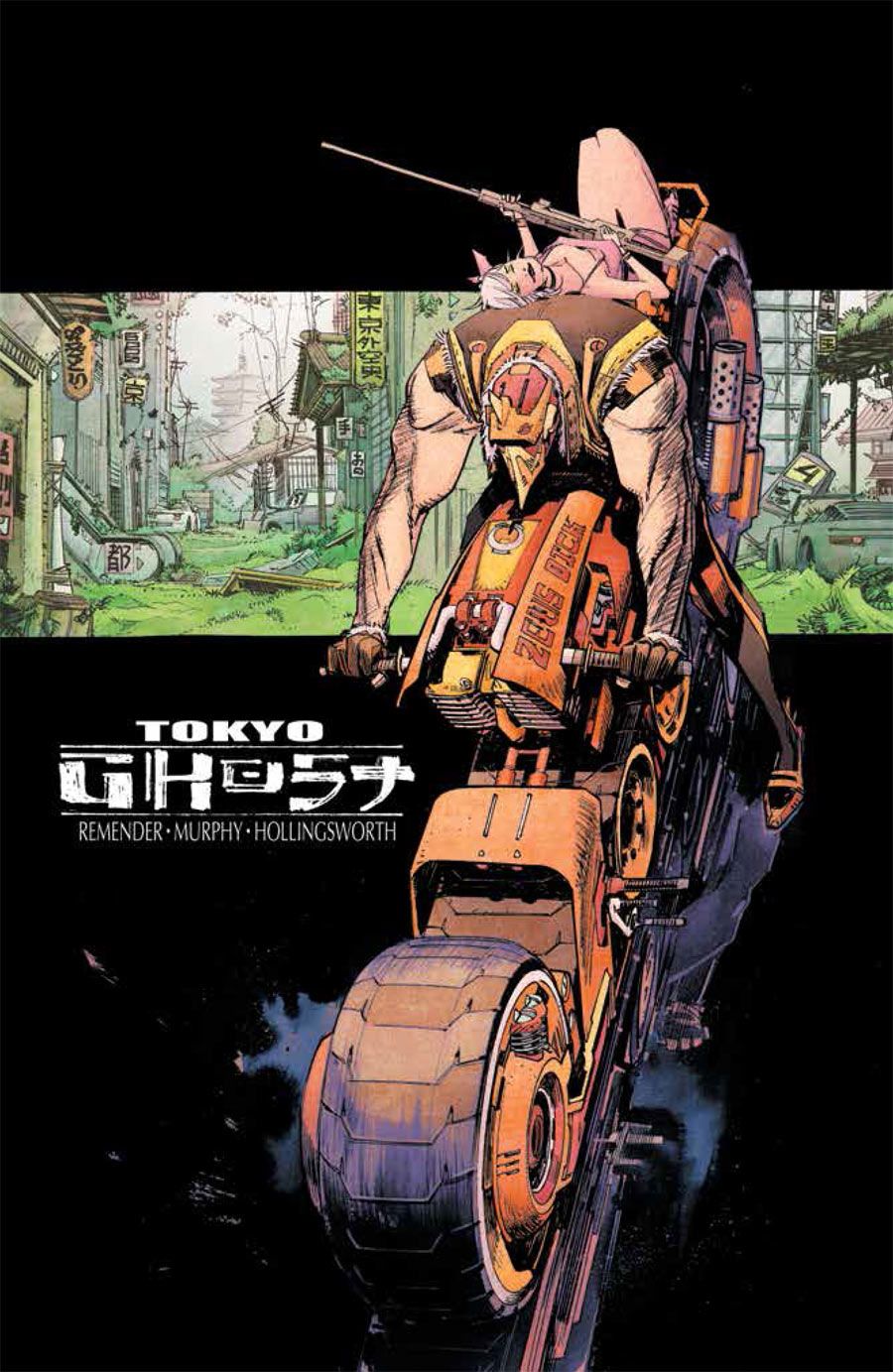

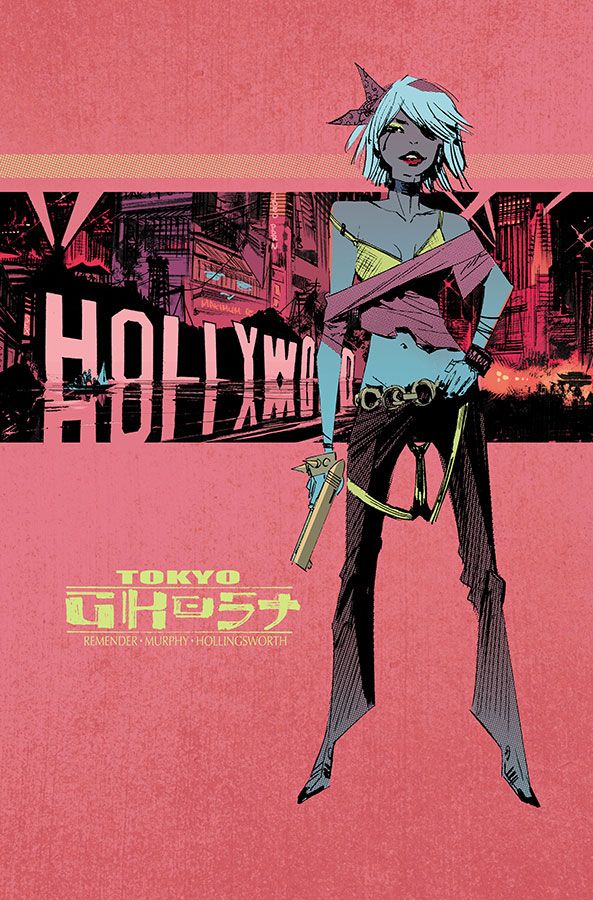

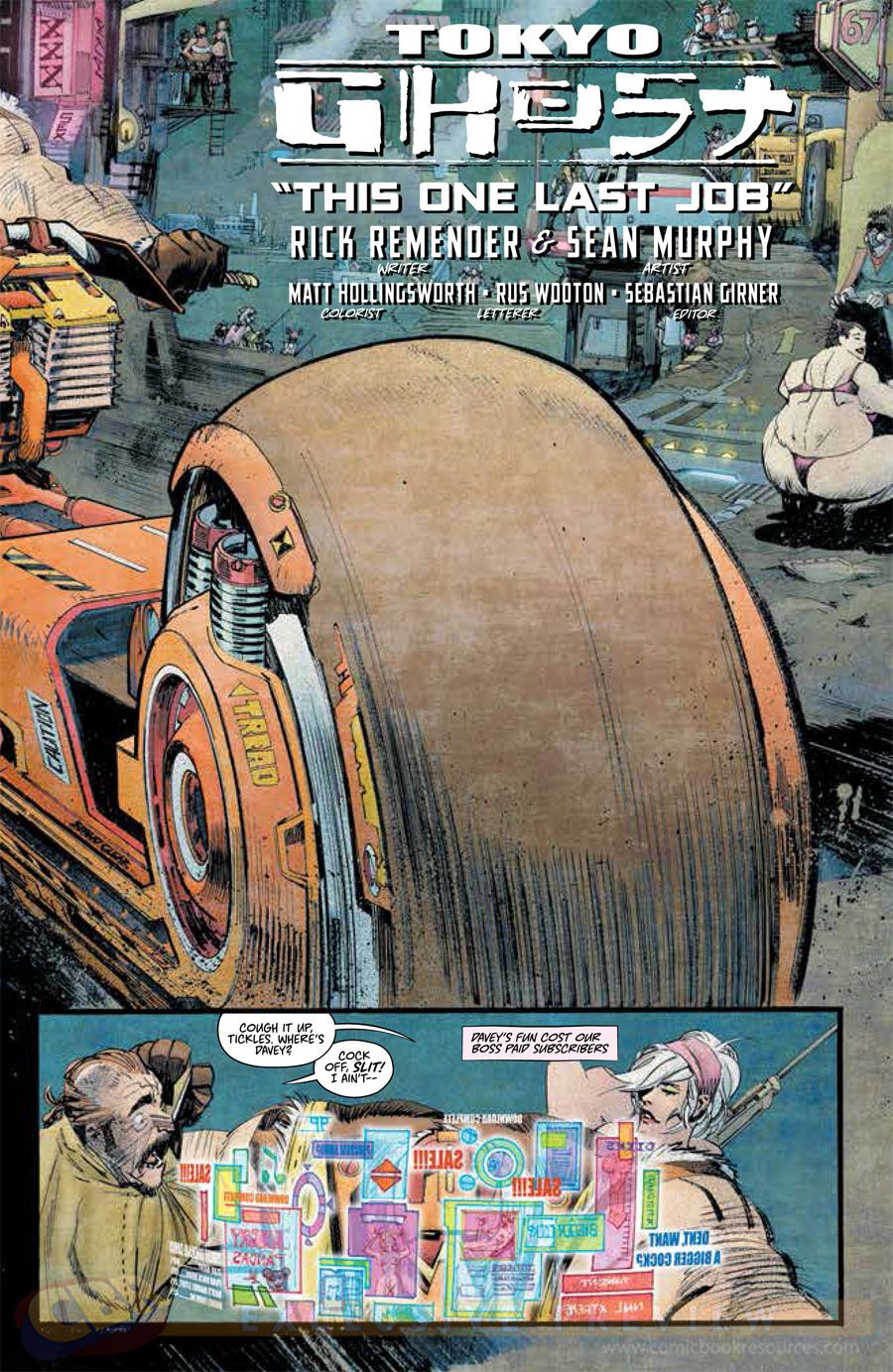

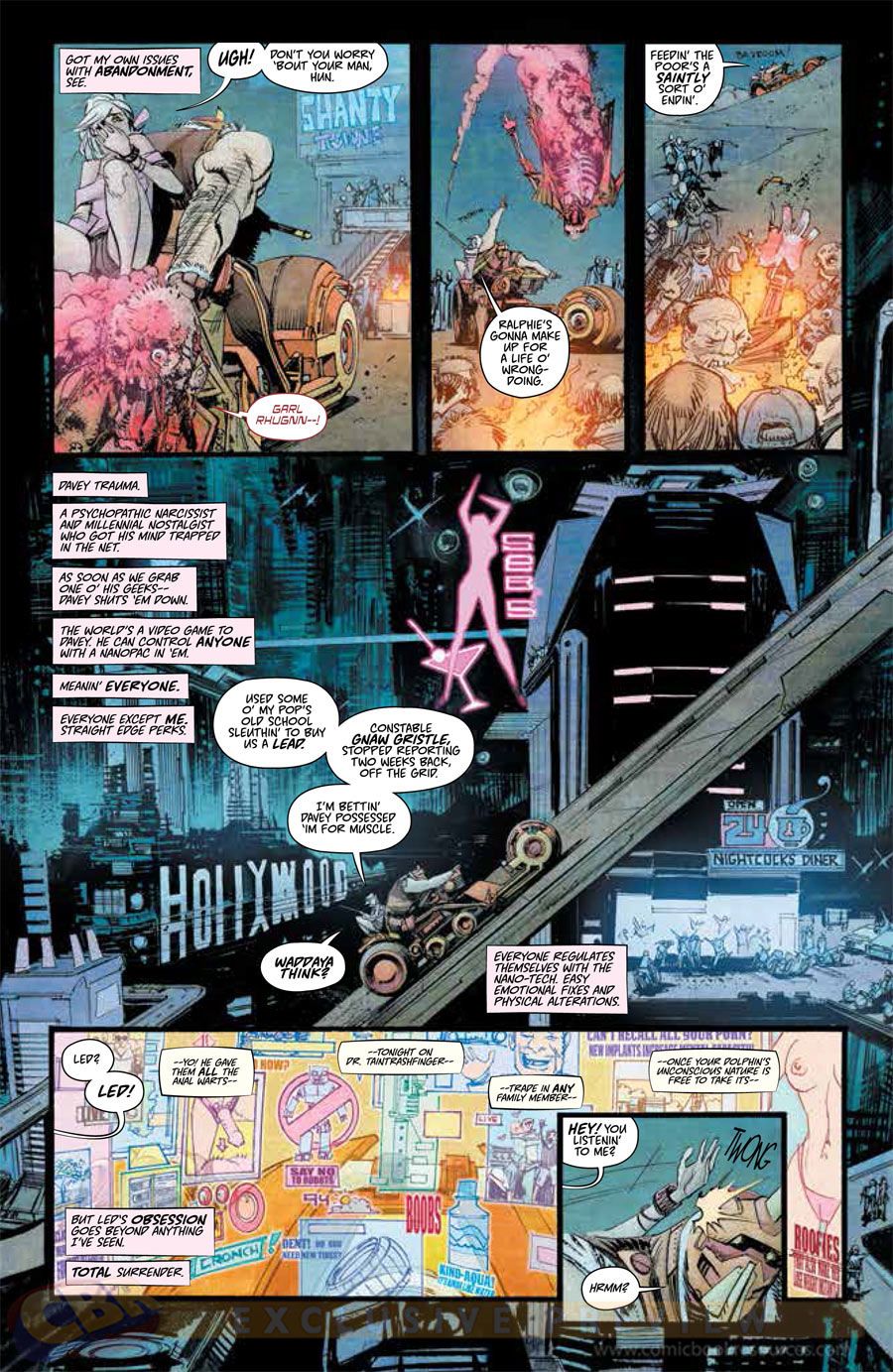

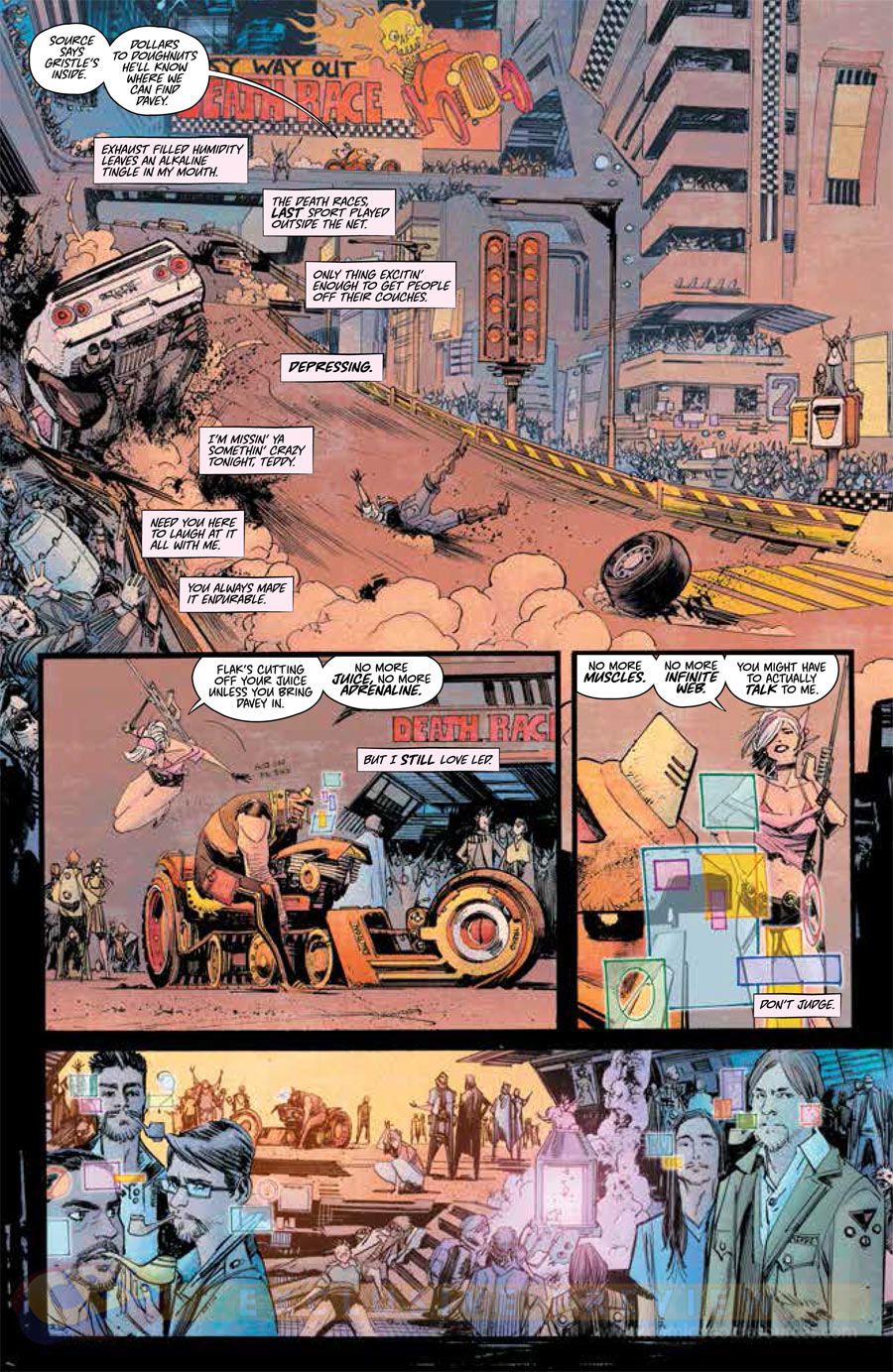

This September, Remender, artist Sean Murphy and colorist Matt Hollingsworth launch "Tokyo Ghost," transporting readers to a tech-addicted dystopia. The Image title is series of contrasts that homage the creators' favorite bleak visions of the future, as well as things like samurai movies.

In a an open and honest discussion with CBR News, Remender explains how he balances writing multiple titles, the ways in which modern society's tech addiction helped inspired "Tokyo Ghost," and why --though he's not ruling out a return to Marvel in the future -- he's now focusing solely on projects owned by him and his co-creators.

CBR News: Let's start off by talking about the fact that for the foreseeable future, you'll be working strictly on creator-owned books. What made you want to move in this direction? And would you like to return to Marvel someday?

Rick Remender: Yeah, who knows? I just know that for right now we've got some illness in the family, and I need to be more available for that. That was one of the major points in my decision. I've really had the pedal down over the last few years, and I haven't had a whole lot of time to be present. Now, there's a lot of need for my attention. So that sort of lit the fuse.

The other half of that is, I'm very much enjoying making creator-owned books and want to keep my focus clean. I'm working with a lot of terrific people, and we get to do whatever we want in exactly the way we want to do it.

Returning to mainstream comics, though, is an absolutely open possibility. I don't know what the future holds. I know that for right now I'm really enjoying doing the creator-owned books and will be doing them exclusively for the foreseeable future, but who knows where the road will take me? If people stop buying the books, that's that. I had a lot of fun doing a lot of the different books I did at Marvel. It was definitely very hard to leave some of the cool shit I had lined up there.

I've been very fortunate in that I've been able to experience both aspects of my dream, which was the 12-year-old kid who desperately wanted to play in the Marvel sandbox, and the more adult guy trying to process unique ideas and philosophies about what's happening to him via creator-owned fantasy.

A lot of people who first came to your work via your Marvel projects may not realize that you had been doing creator-owned books years before your first Marvel work. Now, you've developed a business model that lets you juggle a number of creator-owned titles. In a way, is this like coming home?

It very much is. I had been doing creator-owned comics since about 1997-1998. I shifted my life to continue to do them, because it was very addicting. Nothing was ever more satisfying to me in terms of creative liberties than creating something out of thin air that is owned by the people who make it and is, hopefully, personal and has some craft to it

I did that for 10 years before I got to Marvel, and a good portion of that time was spent working with Eric Stephenson at Image. I really think that where my career was, it was Stephenson's belief in me back in 2003 and 2004 that really made the biggest difference. He basically told me, "We like what you're doing. Just do whatever you want." I did. I went kind of crazy. [Laughs]

It was like, "What?" And the next thing I knew, I had, like, a hundred books. [Laughs] So I'm sort of used to having a lot of projects going, because I have ideas and there's artists that will draw them. What's the old saying? "It's heaven and hell to have nothing between you and doing what you want to do."

It's very fulfilling to make a great comic book with a great artist and create something. But at the same time, too much of that can definitely wear you down and make you tired. Then, another idea comes up, and another great artist becomes available, and you just go, "Well, I don't need weekends as much as I thought I did," or, "I bet I could work harder Thursday and Friday and do 14-hour days." [Laughs] You negotiate and you find ways to make the project happen.

Have you set a limit for yourself on the number of ongoing series you can juggle at one time?

Sensibly, I can do five books in a month and still have time off with my family. It's a busy schedule, but with the hours I work, I can get that done and still breathe. Once it starts going over five, that's where I start to become very sad inside, [Laughs], and the joy of making the art is sort of seeped out of the process. It becomes making the donuts. I kind of grumble my way down to my basement studio and shut the door and weep as I type.

That should never be the case. I'm trying to keep things regulated, and right now all the Image books I'm doing have a waiting period. Eery arc will run five issues, and then we have a three-month break while we catch up and catch our breaths. During that time, we put out the trade paperback.

I think that enables me to juggle the books, which, if we're doing about nine issues of each of them, that reduces the overall work load quite a bit. My editor, Sebastian Girner, has it set up to where I'm doing a book every four-five days. That's still an enjoyable pace. You sit down and write five pages, you work on your outline, and you go hang out with the family.

One of the projects you're devoting a lot of attention to is "Tokyo Ghost," with Sean Murphy and Matt Hollingsworth. The title has been gestating for a while now. How does it feel to have it so close to landing in stores?

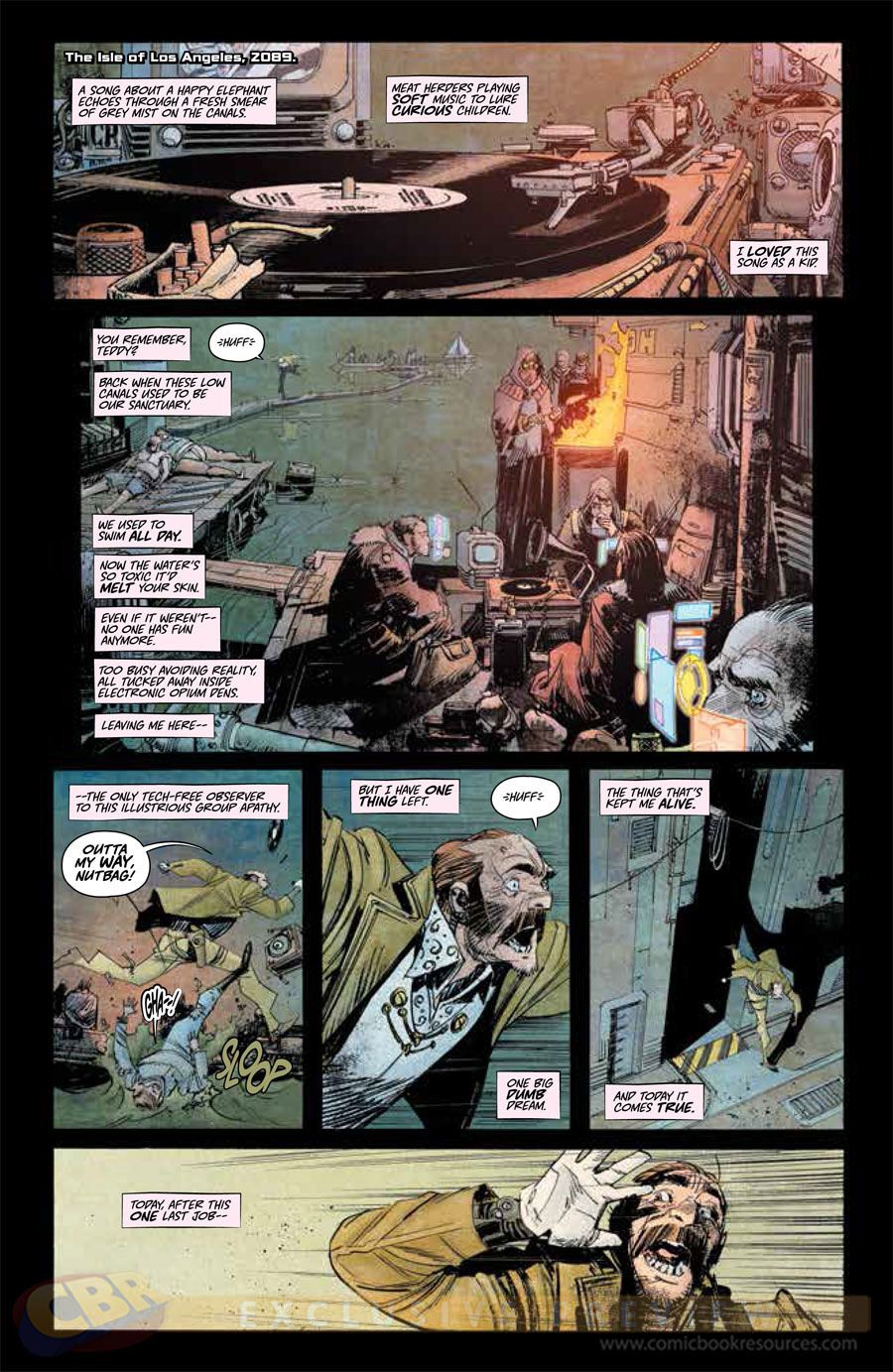

It's exciting. It's the craziest thing I think I've worked on. As Sean and I were developing it, the book snowballed into a Frankenstein monster of these different ideas. At one point during the development, we hit upon a wonderful central theme of exploring our addiction to technology. That's something we've seen in other media, but I really wanted to dig into what I see happening to myself because of my cellphone, and the iPad, and computers. Also, what I see socially. People can't get off their phones at dinner. It's like, "I haven't seen you in a month. Why are you on your phone?"

That became a central theme and was something I really wanted to write about on top of the fictional narrative that we had structured. It's a joy. It's "Judge Dredd" meets "13 Assassins" with, I hope, a very heartfelt message that takes a little while to get through.

The book has been in development for two years, and during the course of those two years, Sean and I got on the phone probably once a week and talked out ideas. Then I would get on the horn with Sebastian and talk out ideas. Ultimately, what ended up being developed was a very rich world and rich story, because we know so much about it from our many conversations. When you see what Sean and Matt have been doing on the art side, it's a real work of art.

That reminds me of a quote from Edward R. Murrow about television. "Our history will be what we make it. And if there are any historians about 50 or a 100 years from now, and there should be preserved the kinescopes for one week of all three networks, they will there find recorded in black and white, or perhaps color, evidence of decadence, escapism and insulation from the realities of the world in which we live."

I think there is an aspect of that. I think that when everybody has a PlayStation 4, it's pretty easy to keep people complacent and distracted as long as they can still afford a cheeseburger, a bag of Doritos, and some Mountain Dew. It does keep people off the streets, from rioting, and being upset. It is a soothing tool, there's no question about it.

I think with all of our technology, whether it be planned as such or just is, there is a soothing aspect that almost becomes a drug. There's an addictive quality to it. There's an addictive quality to the phones and the Internet, the distraction, and I don't know if it's a good thing.

There was an interview with Alan Moore where he was being made fun of for not having a cellphone. He said something along the lines of, "This is a great social experiment that I don't want to take part in." I think that he's really smart too, and it's worth taking a look at. It's interesting that there was a huge population that responded to the Alan Moore interview by attacking him as an old man without being able to see, their lack of inquisitiveness about this technology we're all so tethered to could, in fact, have a negative side effect or twenty to the way we interact, to the way we spend our time, to the way in which we process information.

I think all of that stuff is worth analyzing. When I think about not having my cellphone for a week, it's like, "How will I do my things?" I think becoming so dependent on things is really interesting. Right now, my wife is out of town. She's back in England, and I'm home alone and sick. There's nobody here to take care of the things she takes care of when I'm sick, and I don't know how to do those things. I've crapped on the floor. I'm wearing a can of soup. [Laughs] None of that is true, but you get my gist.

[Laughs] I'm actually talking to you on a non-smart phone. I've never had one, partly because the data plan is pricey, and partly because I watch people I know pull out their smart phone and stare at them so often. It would be nice to have the Internet on my phone, and I'm addicted to tech in other ways, but I don't want to be the guy who's constantly staring at his phone.

It's a tough fight. Try being a parent and your kids are at a restaurant and they're a little bit antsy. The first thing you do is pull out your phone, and you go, "Here's 'Angry Birds.'" You placate them with this virtual drug. It's hard to have kids today at a restaurant, but it's also something we do to placate ourselves as well. Louis C.K. has a bit about it, that nobody will spend five minutes in silence. If you've got five minutes to kill, there's texts to send, e-mails to read, or Angry Birds to fling.

It also has an effect on your attention span. I find it difficult to get through long books, now. I have to really sit down and force myself to finish a 600-700 page book. That's not a huge book, but because of television, Internet, cellphones, iPads, iWatches and iCondoms; all this shit that's infiltrated every fucking aspect of my life, my attention span is shattered.

Then I start thinking about kids who are raised on this shit. I'm from a generation where we didn't have "Pong" until I was five or six. Then Atari 2600 was years later. I remember how exciting it was to see "Pac Man" on a home television.

It's an interesting idea to explore, and I find that anytime I'm doing some hugely fictionalized super future, whether it's "Low," where I'm having fun with a European-style science fiction story, or in this case, where I'm paying homage to things like "Judge Dredd" while tearing down the idea of the character, I think I do a better job when I have something I want to say. I intermingle those two things.

To that end, Sean and I have spent, like I said, a long time digging into the ideas and things we're talking about here. It excites me to write, and I think it comes across in the book.

Check back with CBR tomorrow for Part 2 of our interview with Rick Remender, as the writer digs deeper into the story, characters and world he, Sean Murphy and Matt Hollingsworth plan to explore in "Tokyo Ghost."