"Dunk you under deep salt water / In my dreaming you'll be drowning / Raise me up Lord call me Lazarus / Hey Lord help me make me marvel"

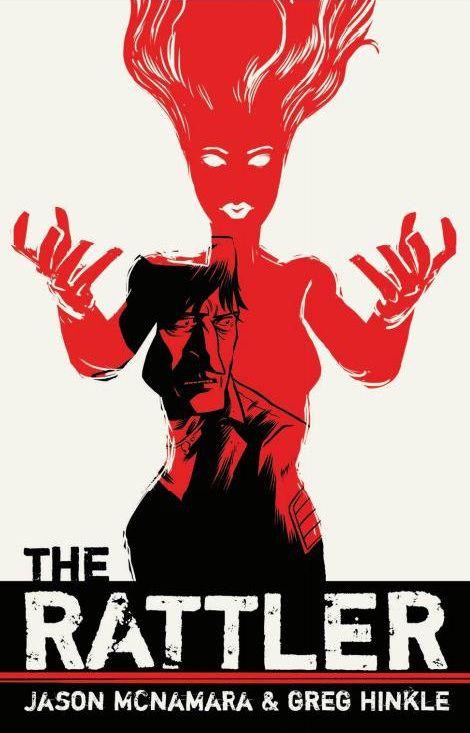

Jason McNamara and Greg Hinkle are Kickstarting their new graphic novel, The Rattler, and McNamara was nice enough to send me a .pdf of the book before the launch (it launches tomorrow) so that people will know about it. The Kickstarter link is here, in case you're interested. So let's get to it!

The Rattler is a horror comic, but in the way that the best horror comics are - as in, there's no supernatural elements (well, if you squint you can convince yourself that there's a bit of that), just people doing horrific things. As most good horror comics, it's drenched in misanthropy, and the world Stephen Thorn inhabits is a dangerous one, with horrors lurking around every corner.

This makes for a taut, extremely efficient thriller, but it also makes parts of the book uncomfortable. The most uncomfortable parts I don't want to get into (for fear of spoilers), but just let me say that there are some disturbing sections of this book, not because of the violence, but because of the psychological underpinnings behind the violence. See, now I'm getting to far afield. I'll back up.

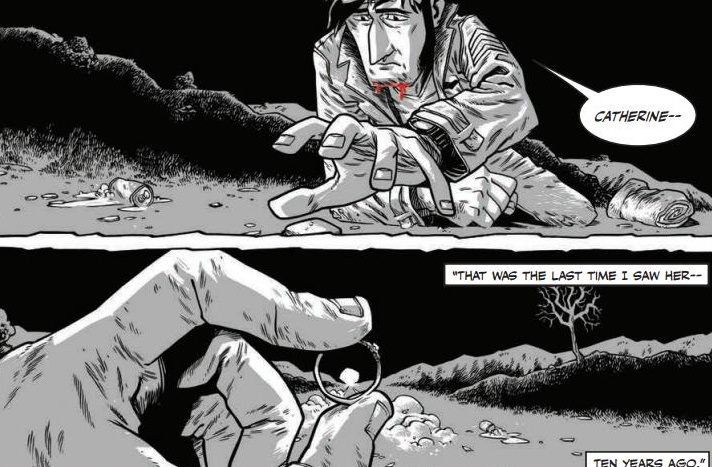

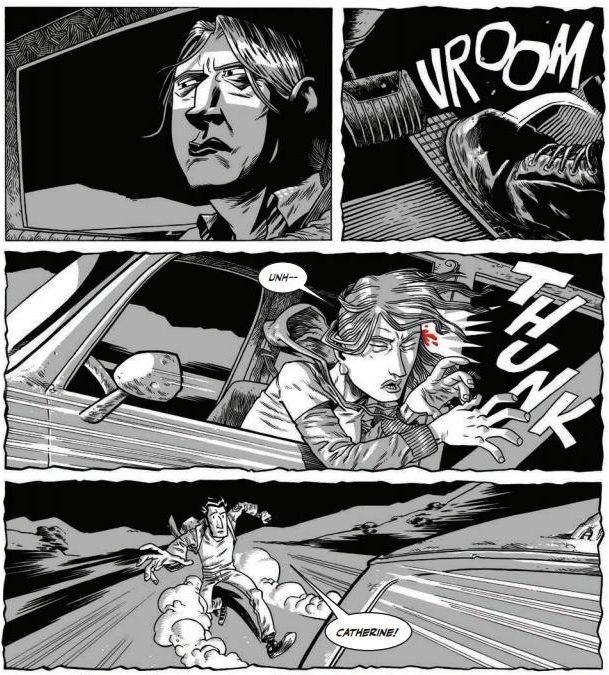

McNamara begins the book on a lonely stretch of rural road, as two young lovers, Stephen and Catherine, run out of gas. A woman in a pick-up stops to help, hooking up a chain to their car and offering to take them to a gas station (she calls it a "filling station," which is oddly old-fashioned - the woman is probably in her 40s or possibly early 50s, so it's not like she'd have been around when "filling station" was a more common nomenclature). With Stephen out of the car to help push it back onto the road, the woman takes advantage and speeds off with Catherine, leaving Stephen alone on the road. Ten years later, he's become a passionate victims' rights advocate, and he's never stopped searching for Catherine even as he's spearheaded so-called "Thorn laws" to continue to punish criminals after they get out of jail (by, it seems, harassing them when they try to re-enter society). It's interesting how McNamara uses standard horror tropes - the lonely road, the young lovers, the malfunctioning car, the kindly older person who turns out to have an ulterior motive - because he obviously knows that they're tropes, but he uses them anyway. What this does is set The Rattler firmly within a slightly askew universe where this kind of thing happens.

McNamara explains at the Kickstarter that he wrote this because something similar happened to him, only the woman he was with was able to escape. This is a horrible situation, certainly, and I don't mean to suggest that what happened to Catherine doesn't happen in real life, but because McNamara uses these horror tropes in the introduction, he sets us up to accept the strange people Stephen meets on his quest. Such people do exist, of course, but the coincidence of Stephen meeting them all (despite using his database's search parameters to find ex-convicts who might have snatched Catherine, which makes it more likely that he would meet them) is a bit much to swallow, unless we're already prepared for it. It's one of the reason why tropes are so useful - already we're able to suspend disbelief, not about what happens to Catherine (which, of course, could certainly happen to anyone), but what happens later in the book. Because, yes, things do get weird.

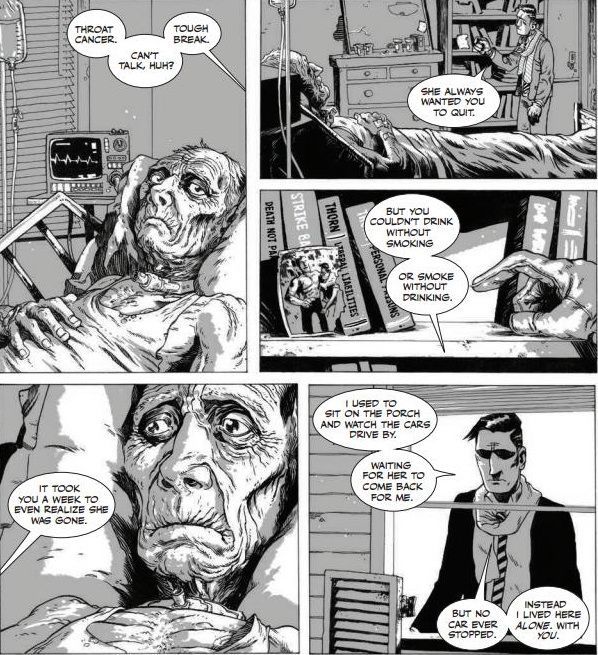

McNamara cleverly doesn't push the idea of Stephen and the surveillance state too hard. When we skip ahead ten years, Stephen is being interviewed about his business and life, which is a handy way to introduce us to what's going on with him. He comes across as a stereotypical "tough on crime" conservative, but McNamara leaves it there and doesn't push that aspect of his personality too much. We learn that Stephen has psychological damage going back to before the incident with Catherine, as his father dies early in the book and we discover that the old man was a poor role model, drinking and smoking himself to death and not realizing for days that his wife had left him.

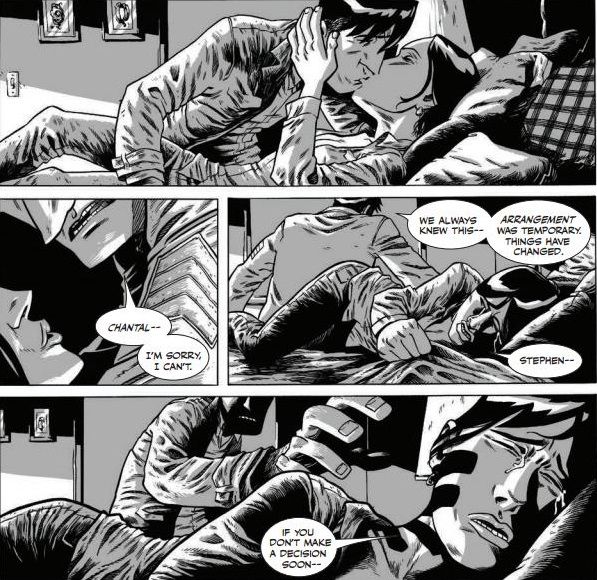

He changed his name, and McNamara leaves us to wonder whether he chose "Thorn" after Catherine, when he became a "thorn" in the side of ex-cons, or if he chose it to spite his father in the same manner. When he visits his dad, McNamara makes it a bit obvious why he's so obsessed with Catherine, as Stephen states it explicitly (it's a rare misstep in the script, which is often quite subtle), but it also reveals that his obsession will take him to places psychologically healthy people will not go. He's in a relationship (he calls it an "arrangement") with Chantal, his majordomo, but it's clear that he views this as a simple sexual exchange, nothing more, which is another marker of his fractured psyche. There are hints, obviously, of The Vanishing in this comic (I've never seen the original, so I'm going by the American version), except that McNamara makes Stephen far more broken than Kiefer Sutherland was.

When his father dies, Stephen's quest for Catherine is renewed (through something that, again, we might call supernatural), but it immediately takes a detour when the ex-con he's been harassing shows up at his house. Through a violent set of circumstances, the ex-con is killed, and Stephen panics, taking the body with him and going on the lam. He manages to search his database and come up with several suspects for Catherine's disappearance, and he starts seeking them out. Meanwhile, a federal marshal is on his trail, as are Chantal and Kaizu, an IT guy from Thorn's company. The book turns more and more horrific, as Stephen starts to uncover what exactly happened to Catherine a decade ago.

Without giving too much away, I'll say that McNamara keeps up the tension, taking us really to a logical end, but the pacing of the script means the surprises (which may or may not surprise you, depending on how good you are at this sort of thing) come in nice intervals and in interesting ways. In one situation, it appears Stephen is in for a world of hurt, but we're not sure what happened to him until Chantal watches a video of the incident, allowing us to experience it the way she does (which also, of course, narrows the point of view, as we're only seeing what the camera lens picked up). McNamara is quite good at doing this - withholding information until the moment where it will have the most impact, which helps with the tension of the story. Reading the book is a fairly white-knuckle experience, and it's partly because McNamara knows how to manipulate the reader well (in the best possible way, of course - manipulation of the reader is a staple of fiction!).

The weird thing about the book is that it's a love story. Actually, it's many love stories, even though the love in it is generally twisted beyond all recognition. McNamara (who has a lovely wife in real life) gets to the core of obsessive love - the only healthy love in the book is Catherine's for Stephen's, and that's partly because it is cut off so early, before it can (presumably) curdle. Stephen can't love "normally" because of his upbringing, Chantal can't love Stephen "normally" because of his obsession, and the other seemingly loving relationships in the book (again, I don't want to spoil things) are broken for various reasons. It's partly where the misanthropy of the story comes from - the bleak world these characters inhabit stems partly from the fact that nobody has a healthy love for someone else.

McNamara takes all these characters and twists them so far that he destroys them, even if they "function" in society. The setting - the grasslands of interior California - throws these characters into sharp relief; there's nowhere for them to hide, so they no longer "function." McNamara once again returns to horror movie tropes by placing the climax of the book in the heartland, a place long associated in horror movies with placidity hiding rot underneath, but because he's done such a masterful job with the characters, the revelations of the final pages punch us in the gut repeatedly.

I've seen only a little of Hinkle's art; I met him in Seattle a few years ago and bought a couple of his self-published books, and I liked the art then, but the art on this book is superb. Hinkle's cartoony style is not unlike Steve Rolston's with a harder edge, and it works really well on this comic. Hinkle gives us strong character work, as his characters are wonderfully expressive - key for a book where emotions lie so close to the surface - and dynamic, which makes the action work really well. Stephen is not a tough guy, as we see from the opening scene, and Hinkle never forgets that, even as desperation gives him some strength - he's gangly, which seems to make people underestimate him (in most cases, correctly) but which helps him when he really needs it. He uses some very neat "camera angles" in the book to heighten the tension and create unusual ways for us to see the action, emphasizing the right things so that we remember them later and so that some things are hidden until the last moment. He's excellent at creating horrific visuals in certain places, like when Stephen finds himself locked in stocks at one point, and he's also fluid enough so that the car chase in the middle of the book flows very nicely over the pages. One reason the book looks so good is Hinkle's inking, which adds a lot of beautiful details to the work, like when Stephen staggers ashore after a car crash and collapses on the bank.

Hinkle also uses grayscaling to incredible effect, as the layers of black, white, and gray add a lot of nuance to the work, making a cornfield shimmer in the night like a terrible chasm or making Stephen's dad look like a mummy covered in ash, and the fact that the only thing colored in the book is the blood hits us hard whenever it shows up (which is, naturally, quite often). Hinkle's world, like McNamara's, is a terrifying place, and the art makes the script even better, which is always nice.

I like both McNamara and Hinkle as people; I know McNamara a little better and think he's one of the funniest dudes in comics I've ever met (if you ever see him at a con, park yourself and just ask him about his career, and you'll hear some stories), so I can't claim to be a truly objective reader, although, as with everything I read by people I know, I try very hard to be so. As I noted at the top, some aspects of The Rattler, which I really don't want to discuss, bothered me more than some of the more pure horror. That might be just something I noticed, however, and others might not be bugged by it (sorry, again, for being vague). McNamara doesn't push the envelope too far with the plot, but that's not the most important thing in a work of fiction anyway, because unique plots are hard to find. Hinkle's art is stunning, beautiful when it needs to be and disturbing when it needs to be, and McNamara's writing, for the most part, makes us think more than simply freak us out, which is a mark of good horror. McNamara gives us people we don't want to know but in whom we can see some parts that strike close to home, and he doesn't give us comforting answers. That's pretty cool.

As I pointed out above, the Kickstarter for the book is starting tomorrow. There are some neat levels, so give it a look. Or don't. It's all about choices around here! But you could do a lot worse with a few minutes of your time!

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ☆ ☆