I don't love titles with the creator's name in them, but there you are.

The other day I received Tale of Sand, the comic adaptation of a "lost screenplay," in the mail from Archaia (Stephen Christy, specifically, who wrote me a nice note as well). I appreciate the fact that they sent it off to me, because I didn't pre-order it, so I'm glad they sent me a copy.

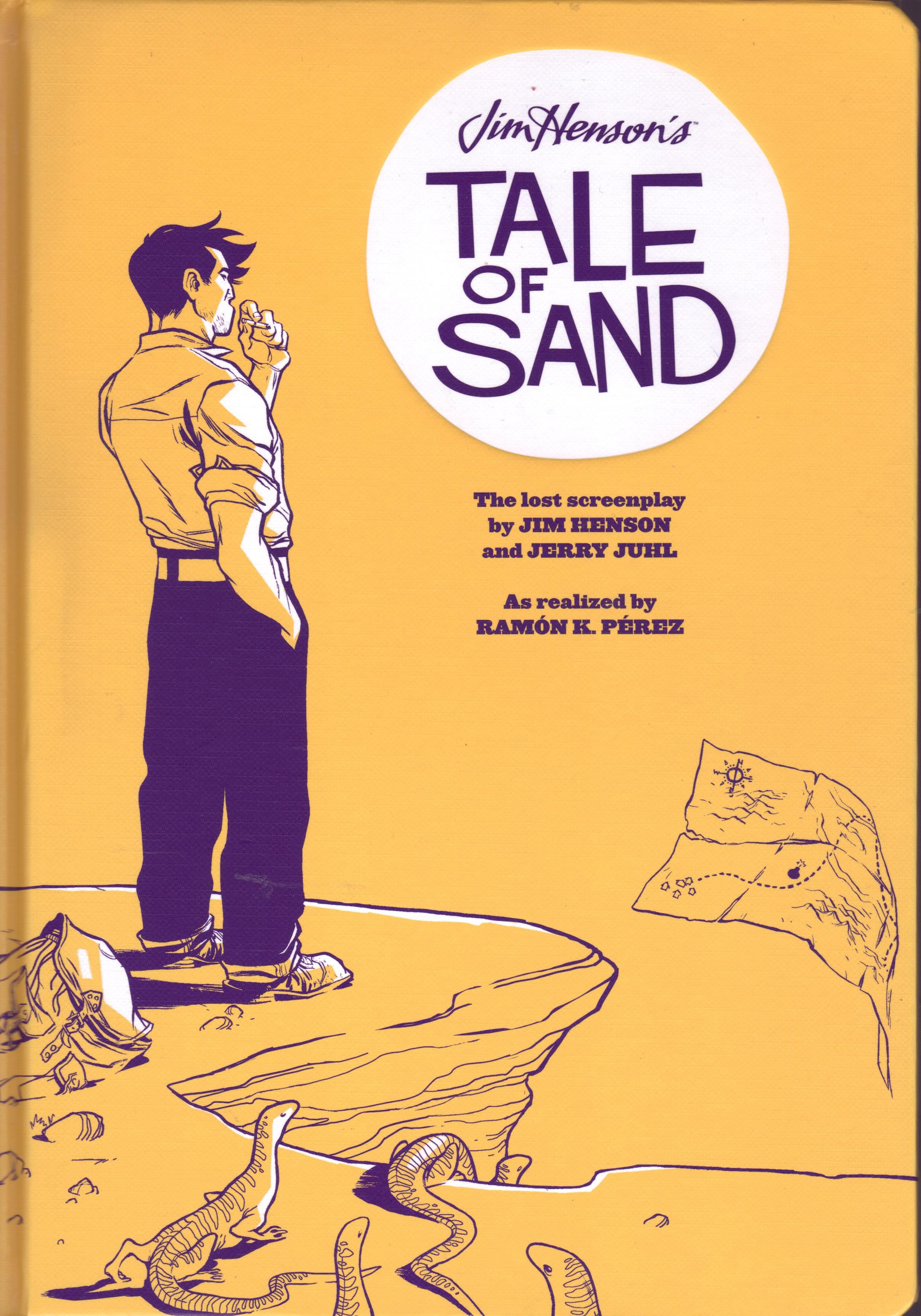

It's written by Jim Henson and Jerry Juhl, his frequent writing partner, and it's drawn by Ramón K. Pérez. It's colored by Ian Herring and Pérez and lettered by Deron Bennett, with additional inks by (deep breath): Terry Pallot, Andy Belanger, Nick Craine, Walden Wong, and Cameron Stewart, and additional colors by Jordie Bellaire and Kalman Andrasofszky. It costs $29.95, for which you get a nice, sturdy hardcover filled with gorgeous artwork.

Some of the interest in this book lies in the fact that Henson and Juhl wrote it in Henson's pre-Muppet Show days, when he was experimenting with a lot of different ways to tell a story. Tale of Sand is a screenplay from 1967-1974 or thereabouts, but Henson and Juhl couldn't get it made, and it was filed away. Years later, the archivist of Henson's company found it, presumably while she was cleaning out the garage or something similar. "Hey, look! it's a screenplay!" she no doubt yelled, and from there, it came to life as a comic book. It's a neat story. Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, Henson was writing some surrealistic stuff (which bled into The Muppet Show, of course, but reined in a bit), and Tale of Sand is a good example of this. Don't read this expecting logic, in other words.

The plot, such as it is, involves a man (who is never named in the dialogue, but is called "Mac" in the screenplay) who shows up in a town where a celebration is occurring. It turns out the townspeople are celebrating him, as he's a participant in a weird event in which he must flee across the desert (the story takes place in the American Southwest, more or less), chased by various "bad guys," in order to reach Eagle Mountain, where he'll be safe. Off he goes, with a ten-minute head start, a backpack full of odd stuff, and no idea what's going on. He enters a bizarre world where anything goes and nothing is as it seems. Ultimately, there are two ways this story can end, and it ends in one of those two ways. I'd love to be more specific, but basically, the plot doesn't really matter.

Henson and Juhl are doing some different things with this story, but "what happens" doesn't really enter into their thinking. They're definitely evoking moods, especially a uniquely American mood of expansionism, individuality, and a severing from the past.

These themes can be positive or negative, and Henson and Juhl make them an interesting blend of both. It's not a coincidence that this book is set in the American West, which has existed in imagination for centuries as a place where people can go to re-invent themselves (it doesn't matter if the "West" is Massachusetts or Arizona), and in Tale of Sand, we get a man who appears to have no knowledge of who he is or what he's doing in this town. He's a rough-hewn 1950s American figure, and it's perhaps not a coincidence that the man chasing him appears to be a somewhat effete European, complete with cravat, tail coat, spats, and devilish Van Dyke. He chases Mac through the desert, armed with seemingly endless resources, while Mac is left pulling strange things out of his backpack ... which of course turn out to be rather helpful, another sly example of American ingenuity. Mac is constantly thwarted whenever he seems to make headway and he's constantly being attacked by allies of the main bad guy, who simply throws money around to get people to do what he wants. Mac also meets a sultry woman, and as we know in popular culture, one can never trust the woman! (Which isn't really fair; Mac can't trust the old coot he meets either, but the woman is more devious about betraying Mac.) Mac is hunted by Arabs, football players (the Green Bay Packers, specifically), the sheriff of a broken-down town, and World War II soldiers (among others). Ultimately, of course, Mac can't trust anyone, not even the seemingly kindly sheriff of the original town, who seems helpful. He also can't escape his past or rely on his individuality, and while I doubt if Henson and Juhl were trying to explode these American myths too much, it's interesting that they end up with that. There's even a hint of sending a scapegoat out into the desert, Biblical-style, but Henson and Juhl don't go too deeply into that, but it's intriguing that they imply it.

The story itself relies heavily on the artwork - there is very little dialogue in this book, so the burden falls on Pérez. Henson and Juhl let the art speak for itself, as the script pulls back the curtain and turns the entire comic into a metafictional event.

Henson himself shows up in the book (unnamed, of course), directing the action and making sure everyone herds Mac in the right direction. When Mac is about to be hanged, the person placing the noose around his neck wears a T-shirt reading "Staff." The sly humor of the book helps keep it from being too much of a downer (the ending is somewhat depressing, after all) even as Henson and Juhl explore more existential themes than those of American exceptionalism. The monotony and redundancy of life is on full display here (yes, monotony, even if the book itself is not monotonous), but the fact that Henson and Juhl turn this into a weird, looking-glass kind of world, where a director sets all the action in motion, is somehow comforting. We don't fall into a Camus-like despair when reading this comic because Henson and Juhl make sure the surrealism keeps the more dire themes at arm's length. Mac can't escape, but he's not "real," so we can remain aloof.

As I alluded to, Pérez needs to be great, and he is. He needs to be slightly cartoonish at some points but make sure the figures are "realistic," and he nails it. The marvelous opening pages immerse us in a cacophony of music and dancing, as Mac enters the town and tries to figure out what's going on. Pérez throws drawings onto the page, places panels almost haphazardly, and the different methods of inking and coloring contrast the vibrant party in the streets and the sleepiness of the town in general. The book is full of scenes spread out over the two pages facing each other, as Mac navigates through the desert, which gives the impression of the size and desolation through which Mac runs. Pérez shifts easily from a softer wash to harder lines - it's not quite a split between the natural contours of the desert and the clearly delineated lines of civilization, but it's close - and his inkers and colorists work well with him. Pérez also has to draw a lot of characters, and he does a very good job with that. Mac, his nemesis, and the woman are wonderfully drawn - Mac is the epitome, as I mentioned, of a 1950s tough guy; his nemesis is suave and clever; the woman is a classic movie-star beauty. Pérez has fun with the characters, too - the football players are giant hulking beasts whose faces we never quite see because they're hidden inside their helmets.

They speak in football plays, too, which is quite humorous. The entire design of the book is fantastic, from the cars to the desert to the weird torture machine the Arabs are going to use on Mac. Pérez keeps up with the absurdist themes of the book - he does a nice job with the man running across the desert with a giant block of ice, for instance, and Smokey Bear's appearance is silly and funny. As I mentioned, Herring and his collaborators color the book superbly, adding to the absurdity of it all and allowing the darker themes to emerge slowly.

If you're looking for a book with a tight plot and a compelling narrative, Tale of Sand isn't for you. Henson and Juhl give us an odd comic, full of fantastic, surreal images and a mood that is darker than we expect. It's full of action and humor, so there's that. Henson and Juhl are clever enough to make sure they don't overwrite things - there's dialogue, of course, but very little - but the book demands that the reader slow down because there's so much on the page. Pérez is brilliant on this comic, as are the other artists who worked on it. It's a strange comic, sure, but because Henson and Juhl make sure to keep it light, we never get bogged down. They have a lot to get into the book, and it's impressive that they do so without writing too much and allowing Pérez to bring their more esoteric ideas to life.

Tale of Sand is apparently out at comics stores, but it won't be released in bookstores (or on-line) until January. Not only is it a fascinating relic from an interesting creator, it's a unique and clever graphic novel in its own right. It's not every day you get to read a surrealist comic book, after all!