"When I got back to my empty room I suppose I must have cried"

I knew about Bowery Boys a while back, because when I still had time to do weekly reviews (I have no idea how I used to do them so consistently, but life, I guess, is so much busier these days), I would go to Cory Levine's Twitter feed when he was editing books and see teasers about it. You can check it out on-line at that link up there, I guess, but you know me - I like my comics in physical format!

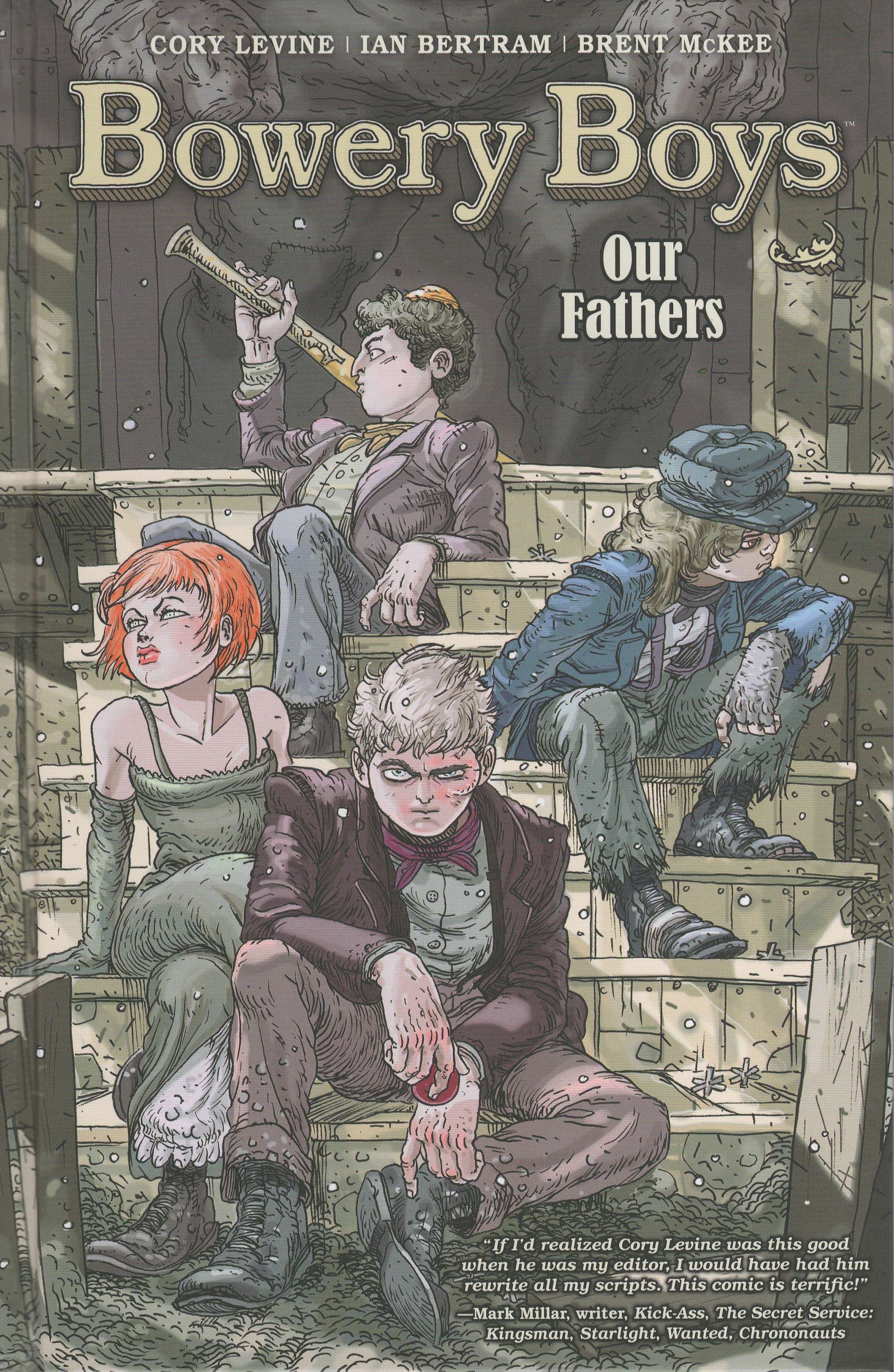

Dark Horse published this in fancy hardcover for $19.99, which is a pretty good deal (naturally, it doesn't have page numbers and I don't feel like counting them, but it's a good chunk of comics). Ian Bertram and Brent McKee illustrate it (Bertram draws most of it, but McKee does the entire final chapter), and Rodrigo Avilés colors it.

Levine's ambitions know no bounds with respect to this comic, as Bowery Boys is a sprawling epic of 1850s New York, with everything that portends. Obviously, there are parallels to Scorcese's Gangs of New York (especially visually, which I'll get to), but Levine makes this his own quite nicely. He tells us a story of Nikolaus McGovern, whose father runs the carpenter's union in downtown Manhattan. George McGovern convinces the union to strike against the capitalist Roderick Pastor, and things go bad from there, as of course they must. But Levine's story doesn't simply follow the plight of McGovern and the union, because he wants to give us a sense of New York society in toto, so we get the introduction of Isaac, a young Jewish boy whose conscience gets the best of him at times, various street urchins, and Mary Ann, a child prostitute. Levine also introduces some interesting villains, including Markus Welsh, an almost supernatural figure who spreads chaos for the right price, and of course the corrupt politicians and policemen who conspire against the working class. Levine wants to set up a book that takes in social commentary as well as being exciting, and he does a nice job with it.

During the course of the book, McGovern is jailed, and that spurs Nikolaus on to save his father, but again, the story twists and turns nicely, as nothing is a clear-cut as it seems.

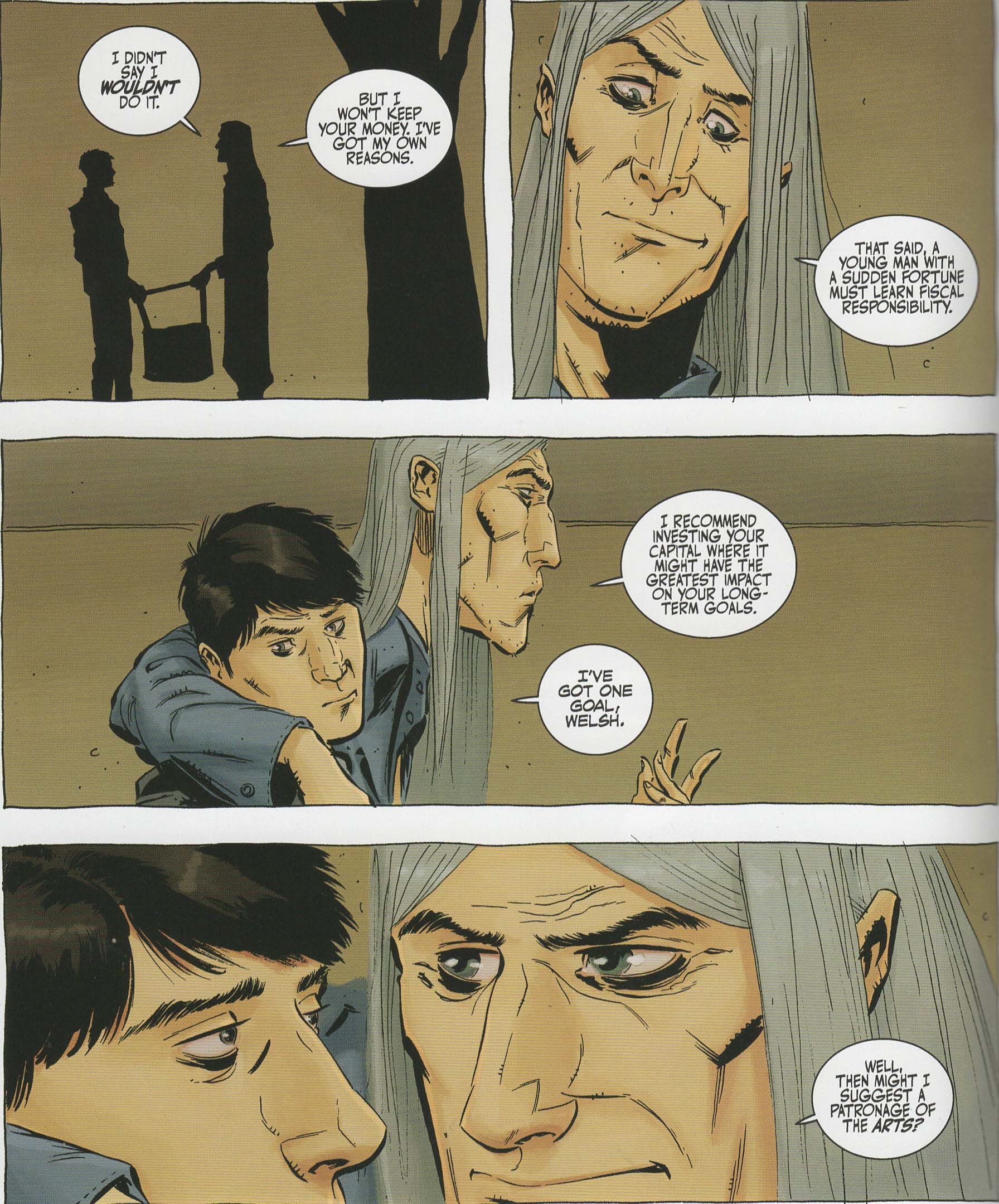

What's really interesting about the book is that Levine resists making anyone a good guy or bad guy. I mean, sure, Roderick Pastor is almost cartoonishly evil, but when Welsh suggests that he needs to be more sympathetic and has a way to do that, we can almost see Pastor's soul dying, and it's pretty chilling. Meanwhile, on the other side, we have McGovern, who rants about the evils of capitalism and believes so fervently in the union that he's willing to do some things that aren't exactly keeping with his rhetoric to save it. Isaac is a child, so of course he has the wide-eyed innocence of a child, and when he calls his rabbi on it, he is chastised for it. However, it becomes clear that he is able to see things almost more clearly than the wizened and (supposedly) wise rabbi, who has become too much of a politician and less of a spiritual leader. Nikolaus, of course, is wildly naïve about life on the streets despite living in lower Manhattan, and when his father is dragged away, he has to learn things in a hurry, and he doesn't always like what he discovers. Even Welsh is not wholly evil - he's a man who understands the economic reality of living in New York, and he takes jobs accordingly. Levine not only examines the economic stratification of society, but other social problems of the time. Pastor is wildly anti-immigrant, of course, as are many others in power, even the Irish cops who are watching McGovern when he's in jail. The 1850s were a wildly anti-immigrant time (the Know-Nothing movement was prominent during this brief time), so it's not surprising that Levine gets into it, and he does a pretty good job showing the various ways immigrants were treated poorly.

He even brings in such things as the way fire departments were organized in the 1850s, which is an interesting side note. There's a lot going on in the book, but Levine balances everything quite well.

He can't quite stick the landing, though, and it's a disappointing ending to a strong narrative. First, he kills off the most obvious person he can, and while I had a feeling it was coming, it was still sad to see him fall into that trap. Then, in the final chapter, he ends the book abruptly without really resolving his central narrative. Nikolaus gets the means to destroy Pastor, and he has a plan to do so, but then ... the book just kind of ends. Levine sets everything up for a big, operatic ending, and while his point might be that life doesn't work out that way, it's not like Nikolaus doesn't have the opportunity to do what he wants. Again, perhaps Nikolaus really does think what he does is the right thing, but it's just very weird that in a book with so much grand posturing, the final scenes play out really limply. The subtitle of the book is, of course, "Our Fathers," and Levine does show that sons will do what they need for their fathers, no matter if or how badly the fathers have disappointed them, but it's still very strange that the deus ex machina in the book comes from such an out-of-the-way source. It's a very frustrating ending, and it colors the way I, at least, see the rest of the book. I don't know why Levine chose to end it the way he did. I can't imagine he "ran out of room," but that's what it feels like - like he had a page limit and he was getting close to it, so he simply wrapped everything up. It's too bad.

The other disappointing aspect of the book is the artwork, but not because Bertram or McKee are bad artists.

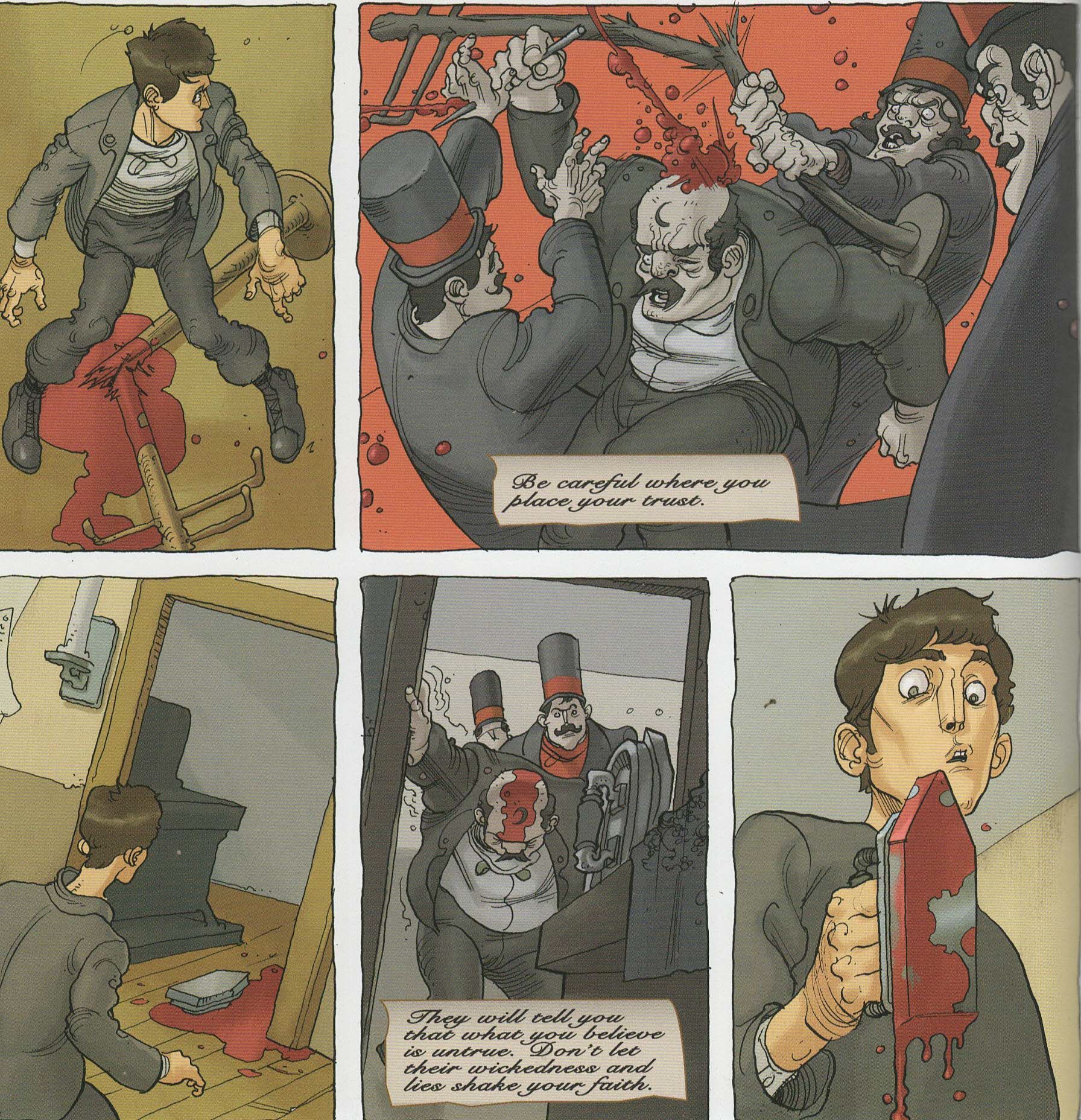

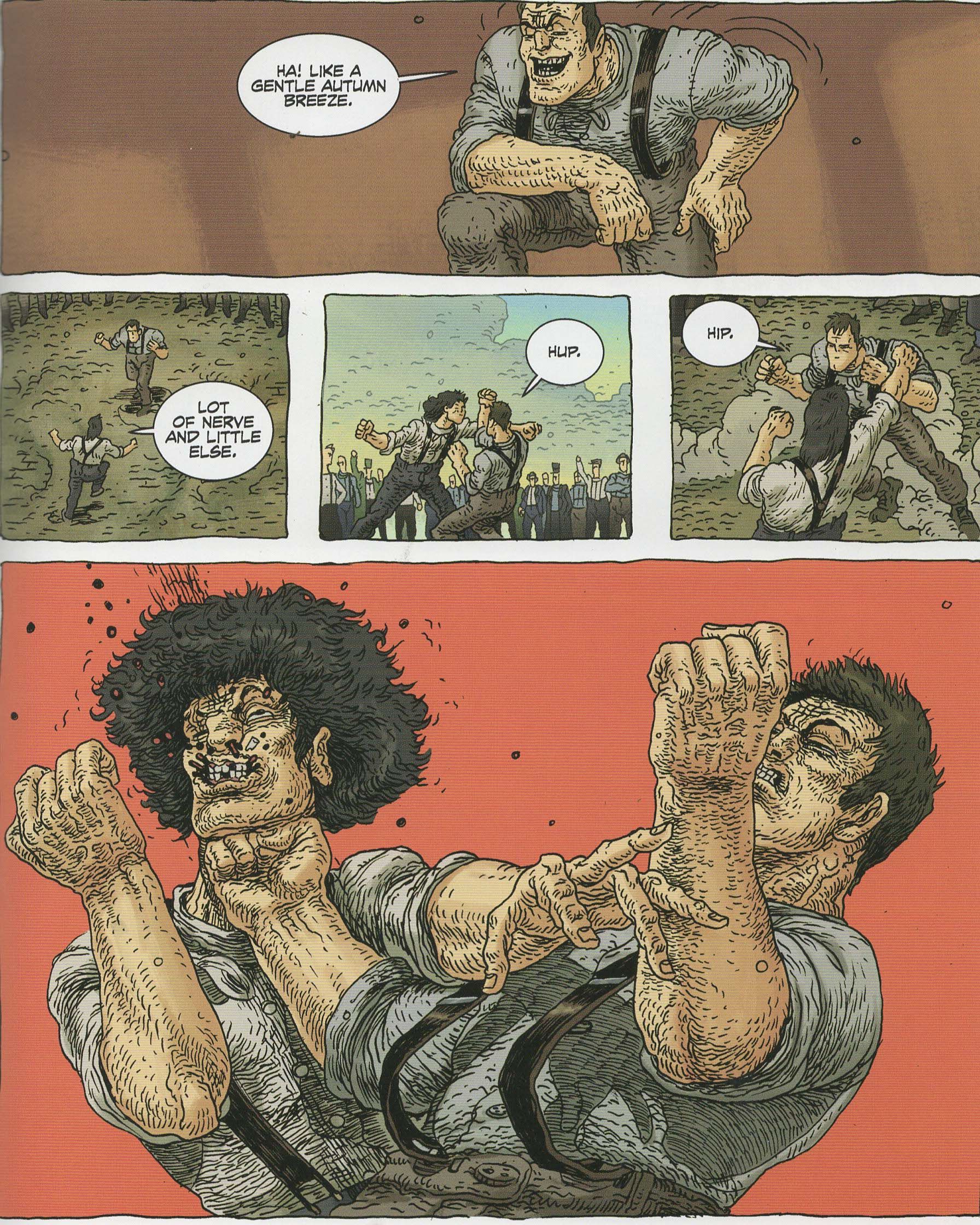

The disappointment is that one of them couldn't do the entire book, because their styles are so very different. Bertram is a terrific artist, and his overwrought cartoonish style seems to fit the epic feel Levine is going for in the book. His Pastor is a stuffed popinjay, with a ridiculously large bow tie and tiny porcine features, while his Markus Welsh is a whirling dervish of malice, his rabbi is a gnarly and rotted crypt-keeper, and his Bo Bisbee (a violent enforcer who Pastor gets released from prison to track down McGovern) is a big, bombastic fool. Bertram does a wonderful job keeping his characters just on this side of caricature - yes, they're often designed to be stereotypes, but he makes sure the world they inhabit matches them, so his Manhattan is crowded with people and full of menacing alleys and dark, poorly-built rooms where vile men scuttle around plotting against the union and the capitalists. He uses hatching really well to make his characters look rough-and-tumble or simply beaten down by life, and his violent scenes are horrifying. He draws fists and weapons hitting flesh with amazing detail so that it feels really painful, and he distorts characters' faces when they do get hit really well, so that the violence feels uncomfortably real. The characters look like they stepped out of Gangs of New York, as I pointed out above, as Bertram gives them long coats, tall top hats, bigger-than-normal bow ties, while Avilés colors them brightly in contrast to the drabber colors of the working class. The biggest problem I had with the movie and with the way Bertram draws the gang members is that I don't know how historically accurate it is.

I know that when the movie came out, people mentioned how distinctive the clothing was but not whether it was actually the way people looked. If you see portraits of men of the time, they don't look quite so flamboyant, but of course, those are carefully managed portrayals. What strikes me about this comic is something that often makes me wonder - did Bertram, McKee, or Levine do research into how the people dressed, or did they just use the movie as a template? A lot of what we think we know about how things work comes from popular culture, which is fictional, and that sort of thing fascinates me. Bertram draws them very well, but I do wonder if he's being historically accurate. But that's just something I wonder about. If we get back to the art, the problem with McKee's art is that it looks nothing like Bertram's. His art is far less cartoonish, so someone like Pastor, for instance, comes across as far less disgusting because he looks more human and less piggish (even though McKee still draws him as a large man). Daniel, one of the street kids, is a hulking giant in Bertram's section, which belies his naturally gentle nature, but McKee just draws him as a big kid. Nikolaus looks far older when McKee draws him, too, which makes his decisions regarding his future more puzzling, as he doesn't look like someone who would be so ruled by his emotions. Welsh is no longer a freakish creature, but just a man with stringy hair. I should be clear - McKee is a fine artist, and he does a good job on his parts of the book. But Bertram establishes a tone of the comic, and McKee's style just doesn't fit that tone, and the jarring shift is too much for him to overcome, especially as Levine pulls his somewhat flaccid ending and doesn't let McKee draw anything as grand as some of what Bertram gets to draw.

If McKee had drawn the entire book, it would have looked fine - it would have had a different vibe than Bertram, but that's okay. An art change can work perfectly well in some instances, but in this case, the style change is a bit too much for the book to overcome. Perhaps, again, had Levine not ended it so oddly, McKee could have had more chance to do a marvelous set piece, but that's not in the cards for this comic.

It's a shame about Bowery Boys, because Levine is very ambitious and he crams the book with a lot of cool stuff that still resonates today, making this not only a historical comic but a contemporary one, too. He doesn't shy away from the ugliness of xenophobia and racism, he doesn't give anyone easy answers, and he gives us a lot of bizarre and colorful characters. His storytelling is strong until the final act, when it seems like it abandons him. It would have been nice if one artist could have drawn the entire book (I like Bertram's work a bit more, but I wouldn't have minded if McKee had done the entire thing), and it would have been nice if the book hadn't ended so weakly. Even so, it's a fascinating comic, so it might be worth a look if you're interested in this time period and the sordid history of New York.

Rating: ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ½ ☆ ☆ ☆