Written by Upton Sinclair, illustrated by Peter Kuper

Classics Illustrated, $9.99

This is a difficult book to review. There is so much about it that is good, and so much that is bad, that it’s hard to render judgment on it. Some of the flaws may stem from the original (which, I admit, I have never read), but some are clearly the fault of the artist and the publisher. And yet, despite all this, it is a powerful book.

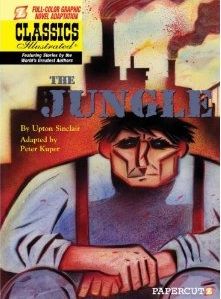

What makes it so powerful is Kuper’s muscular art, which is perfectly suited to the subject matter. His blocky yet expressive style is evocative of social realist art, and he reinforces that by using drawing techniques that suggest woodblock prints or lithographs rather than standard comics art: thick, simple lines, large blocks of light and shade, dropped-out areas, spatters, and fades.

Kuper’s adaptation of Sinclair’s novel also has a poster-like simplicity to it. The hero, Jurgis Rudkus, comes to Chicago from Lithuania with his family in search of a better life, but instead, the whole family winds up working in factories under terrible conditions (The Jungle is known primarily as an expose of the meat-packing industry, although Sinclair intended it to be about the larger issue of the exploitation of the working poor). Jurgis is injured, loses his job, and falls into a depression. His wife falls victim to a lecherous boss, and when Jurgis responds with his fists, he finds himself blacklisted and unable to find work. The family ultimately loses their home, Ona dies in childbirth, Jurgis turns to drink and winds up in jail, their son drowns in a flooded street—the disasters just keep coming. Jurgis goes through many transformations, but nothing—not the union, not the settlement worker, not even the con man he meets in jail—can save him, because the deck is stacked so solidly against him. Even the ending is unsatisfactory: Jurgis goes to a rally, and the speaker fills him with hope, but there is nothing to suggest that this time would be different from all the others. The suffering and the fall are very real, but the redemption feels as if it was slapped on.

Part of the problem is that Kuper has compressed the story into a mere 48 pages, so the narrative reads less as a single story arc than as a series of events, with little prelude or reflection: This happened, then that happened. What’s more, Kuper lets the text carry the burden of narration, relying on text boxes in almost every panel, so the effect is like reading an illustrated book broken into panels rather than a sequential story. Sometimes Kuper jumps from scene to scene in successive panels, letting each one serve as a single story element without strong connections to what went before and after.

The format of this book just makes things worse. The pages are too small, so the panels feel crowded together. Some pages bleed to the margin, while others are surrounded with black, which kills the artwork. And the unfortunate placement of the brightly colored Classics Illustrated logo on the cover ruins the mood of that image.

Still, nothing can ruin Kuper’s art. From the exquisite frontispiece, which shows Jurgis carrying a side of beef through a factory that mimics a gaping maw, to the final images, filled with light and hope, he really does bring the story to life. Each individual panel is a work of art in itself; it’s the way they are strung together that is problematic. With a bit more room to breathe, this could be a wonderful book.

Instead, it is a shrunken and compressed version of a wonderful book. If the page size was a little bigger, if the borders were cream instead of black, if the panels were spread out a bit more—that would do this book justice. (As an model, check out Sterling Publishing’s A Study in Scarlet, one of the handsomest graphic novels I have seen in quite a while.) And while I respect Classics Illustrated as a venerable brand, the screaming yellow logo breaks the mood of Kuper's cover. (An earlier edition actually had a much nicer, toned-down version that fit with the art.)

This book is a reprint; the first edition appeared in 1991, and it was republished by NBM in 2004. Even in this imperfect form, it is a great graphic novel, and while I wish it were more deluxe, the smaller size does make it more accessible to a wider range of readers—which, come to think of it, may be more in the spirit of the original.

(This review is based on a review copy provided by the publisher.)