What happens when the war is over?

That's one question at the heart of Ender's Game, whose eponymous protagonist remains "the hero" even as his actions veer toward villainy. The film erects some big dilemmas regarding culpability and preventative violence, but declines to offer up any real answers with the omission of a few integral plot points. The characters draw their own conclusions, and the audience is left to pick sides.

Technically, Ender's Game is exactly the right kind of adaptation. Writer/director Gavin Hood has updated the world of Orson Scott Card's original 1985 sci-fi novel, modernizing aspects of technology and culture, transforming the plot here and there to suit the screen. Card famously called Ender's Game "un-filmable," but technology and effects have finally caught up to expectation. The special effects really are tremendous, particularly in large-scale battle scenes involving virtually millions of space ships. Everyday tech like tablets and screens are reinvented with fun and flashy Minority Report controls and cerebral interfaces.

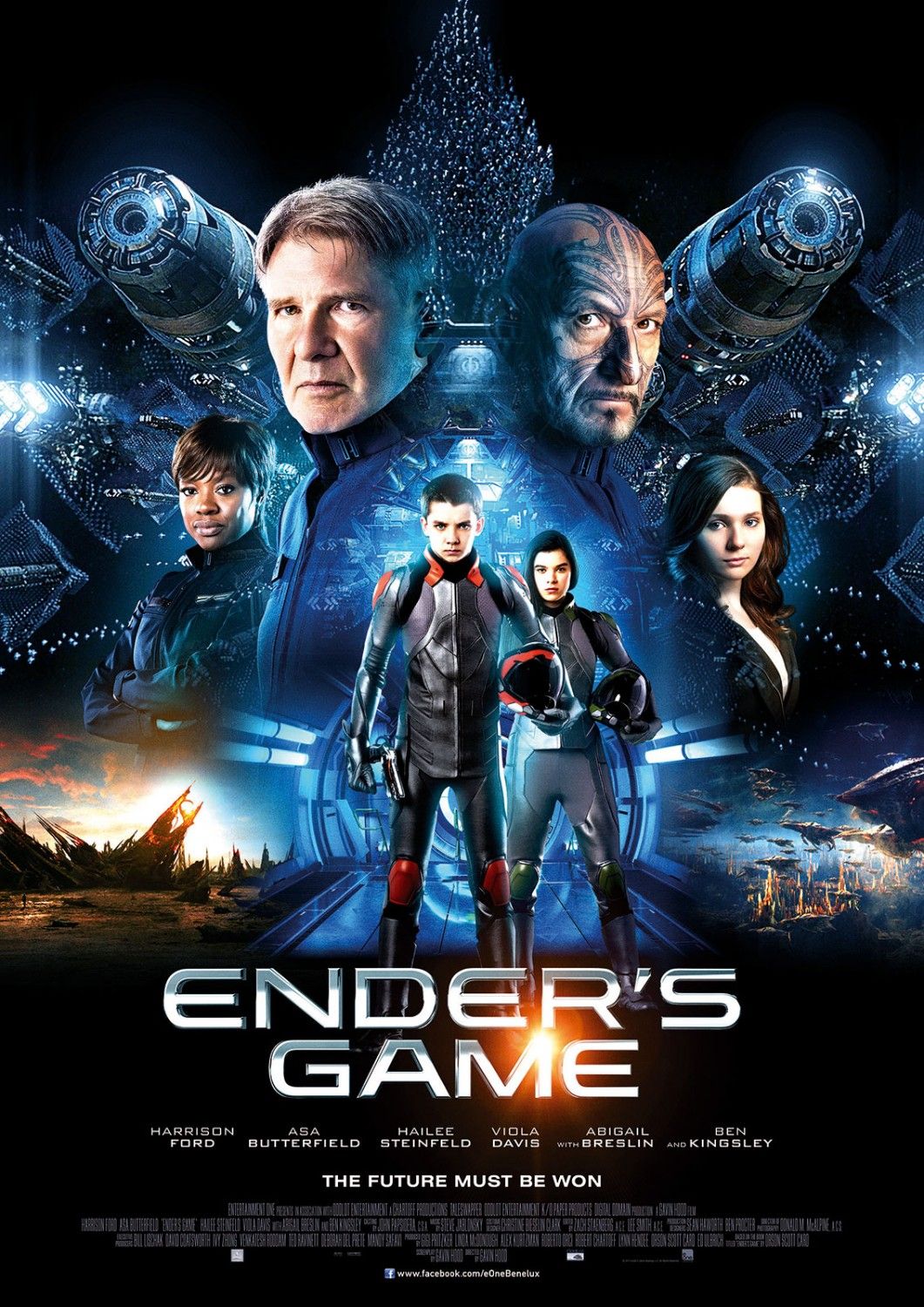

In Ender's Game, Andrew "Ender" Wiggin (Asa Butterfield) is a typical outcast. He's too smart for his own good and just slight enough to be inviting to the bullies of the world, including his menacing older brother. He shouldn't have even been born; having three children is all but outlawed in this future society. But he's smart and talented, and the grizzled Colonel Graff (Harrison Ford) believes he's exactly what this world, fearful of another alien invasion after the first wiped out millions of innocent people, needs.

Graff recruits young Ender to join Battle School, where he learns to fight in zero gravity and conduct space battles like complex operas. His superiors hope he'll eventually prove skilled enough to command the entire human fleet against the ant-like "Formic" alien forces. It's a video game fantasy come to life, though Ender's not exactly the kind of kid who enjoys such things. He doesn't play games for fun -- he plays war games to win.

Butterfield is competent in his role as Ender, letting just enough emotion seep out from underneath the character's stoic facade, and the medium-sized cast of misfit kids who gravitate toward him are all varying degrees of likable. Ben Kingsley also does a great job with the prickly and mysterious "hero" who's introduced in the movie's second half. Ford's Colonel Graff, on the other hand, reluctantly growls too many of his lines, mistaking deadpan for grizzled, though his emotions sneak out as well toward the climax.

Unfortunately, Ender's Game's shortcomings are largely in the cutting room floor. There's a lot of plot for a faithful adaptation of Ender's Game to cover. Hood made an admirable attempt, and the essentials are there. There's enough exposition that viewers shouldn't get confused. But so much was left out of the story by necessity that the movie comes across as overly simplistic.

Butterfield and Steinfeld Discuss the Challenge of Ender's Game

Ender's siblings Valentine (Abigail Breslin) and Peter (Jimmy Pinchak) are relegated to bit parts, for example, the latter appearing in just a single scene. Thus, their clever political machinations (which provide a needed change of pace and scenery from Ender's brooding and training in the source material) are left out. Instead, the two simply serve as dual foils for Ender, extremes of compassion and sociopathic between which he can find balance.

Even without that significant subplot, there's simply too much story for Ender's Game to handle with much elegance. Most scenes have no breathing room, and there's certainly no time for the film to repeat anything or for any points to be driven home. It all moves so fast; Ender grows up before the audience's eyes, but there's no indication how he learns the lessons he does. His peers and commanders grow to respect him, but it's unclear why or how he's earned their admiration besides winning every fight by any means necessary.

Hood's version of Ender is as outwardly confident as Card's original character, but without being inside Ender's head the audience gets too little of his fear and uncertainty. He should be arrogant, but the film makes it feel like his victory is assured from the first scene. There's a sense that he's too smart to fail, which has the dual effects of lessening the tension and making him somewhat hard to root for, especially when he's kicking floored bullies long after they're down.

Hood's direction overall is enjoyable. Ender's Game is "shiny" sci-fi at its finest: there are lots of big toys in space for audiences to gawk at, everything spinning and glimmering brightly. In epic sequences the camera sweeps through asteroid fields through atmospheres down to alien planets' surfaces. In contrast, faces (particularly Butterfield's) are shown uncomfortably close during intense moments, which occur frequently. This intimate effect won't be lost on IMAX audiences. It's a spectacle worth watching, and for many Ender's Game fans, it will probably be plenty good enough. Those free-floating combat training scenes will certainly live up to most readers' imaginations.

But Ender's Game ultimately poses too many big questions without offering satisfying answers. In this world, war is a game; children grow up playing it, and in Ender's case every game seems eventually to bleed into reality. Ender's violence and the morally questionable actions of the adults who surround him always seem justified, but that's because the movie is a one-sided story told by the winners. A brief scene at the end attempts to shift that perspective, but its hesitation to go all the way ultimately helps little.

Were Ender's actions, even the ones that were out of his control, right? The novel has answers, but Hood's more ambiguous vision of Ender's Game doesn't seem to have enough room for them. Fans of the source material can fill in the blanks, but other viewers might find these questions more difficult to swallow.