A few weeks ago, I was glancing at a comic review online. Not for one of my issues, but for an issue by a couple of friends of mine. No, I'm not going to tell you the title, because that's not the point here. As I recall, the issue received something of an average rating, but I honestly didn't finish reading the review.

That's because I got a few paragraphs into the review, and stopped dead when I got to the term "textboxes." I was frankly stunned that someone reviewing a comic on a well-known site would not know the term "caption," and instead make up... well, "textboxes." It's like writing a baseball game summary and calling the shortstop the "middlefielder." Things have names. If you're writing about those things, you need to use their proper names.

Look, I get it. Reviewing comics is not a gig that pays well, or in a lot of cases, at all. People are often doing reviews because they love the medium, or maybe for some free comics. I understand there's not a lot of reward in doing the job. But that's still no excuse to not do the job properly, to not do your homework, or to not know the proper terminology.

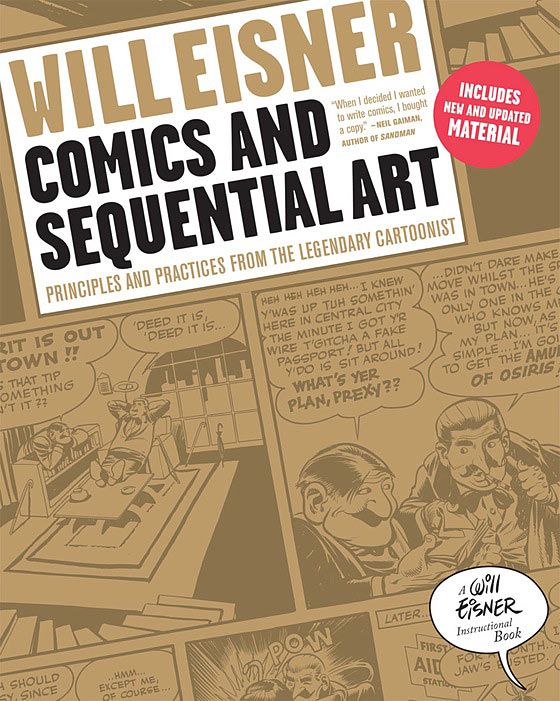

I've previously suggested that comics reviewers... or really, anyone writing about comics... get a basic background in sequential storytelling. For my money, the two indispensable references are "Understanding Comics" by Scott McCloud, and "Comics and Sequential Art" by Will Eisner. The companion volumes (McCloud's "Reinventing Comics" and Eisner's "Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative") are also recommended. But the first two are essential. This is a visual medium. If you don't understand the visual aspects of comics, you can't write about them effectively. For what it's worth, you also can't write comics effectively if you don't understand the visual aspects.

A review is not a plot summary. That's what a fourth grader writes as a book report. "Batman did a really cool thing, and I liked it" is not a review. What happened should never be the meat of a review. How successfully it happened is what a review should be about. Tell the audience why something worked or didn't.

Reviews are also not a venue for what the reviewer thinks should have happened instead. The comic should be reviewed as it exists, not compared to the hypothetical comic that exists only in the reviewer's mind. It's not the reviewer's job to express what Batman would "really" do in a situation.

So first, let's learn some words:

As mentioned, we have "captions" in comics, not "textboxes."

We have word or thought "balloons," not "bubbles." The balloon's "tail" is the part that points to the speaker.

Sequential art is presented in "panels," not "boxes" or "frames" or God forbid, "storyboards."

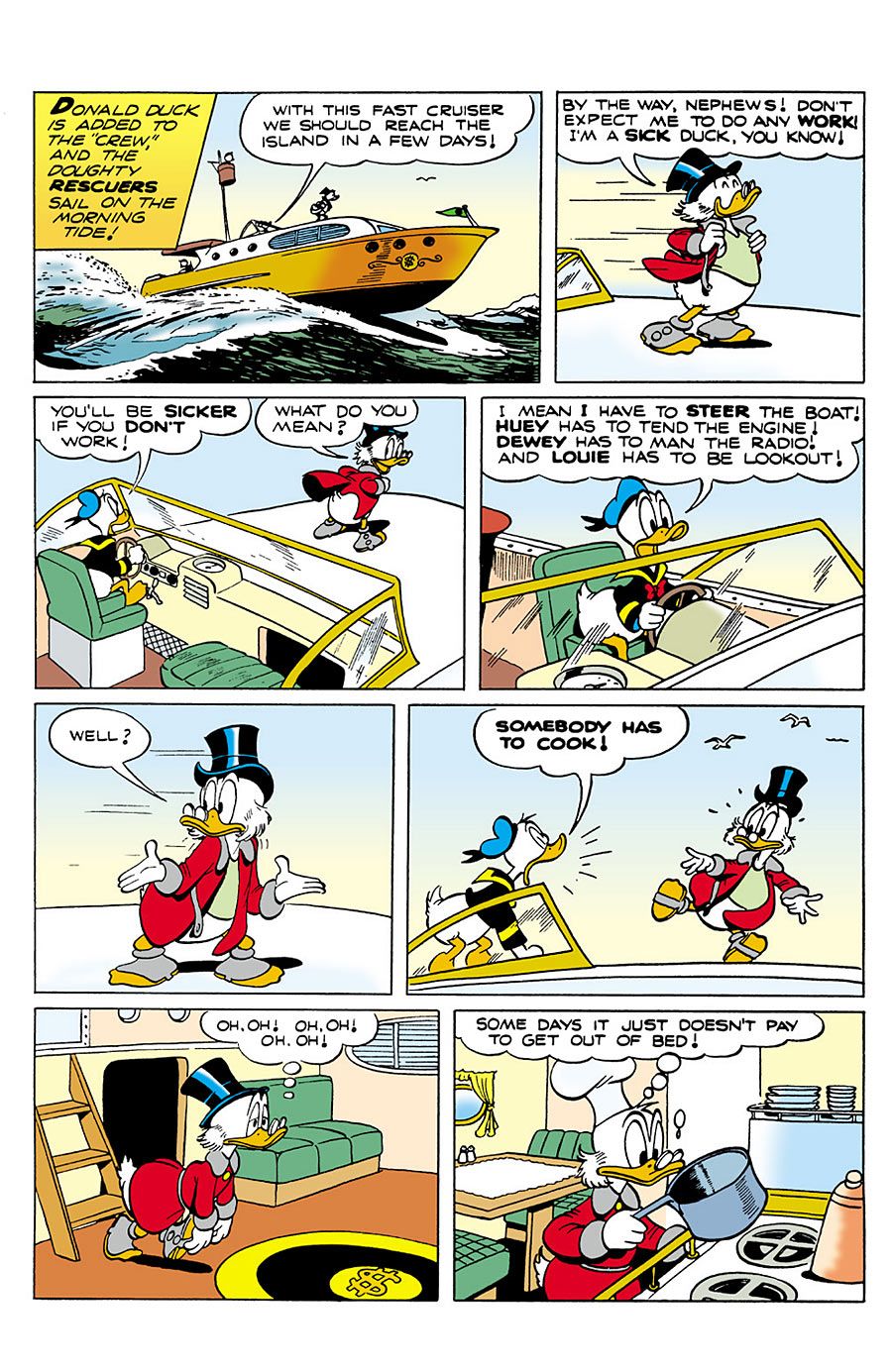

A horizontal row of panels is called a "tier." Traditionally, superhero comic pages often utilized three tiers, while "funny animal" or comedy comic pages utilized four tiers.

The spaces between panels are called "gutters."

The line around the outside of the panel is the "panel border." When an element of the artwork extends beyond it, it's called "breaking the border."

A single-page illustration is a "splash," which can sometimes have an inset panel or panels.

When two facing pages are butted together, with an image or sequence running across both pages, it's called a "two-page spread" or "double-page spread"... not a 'two-page splash."

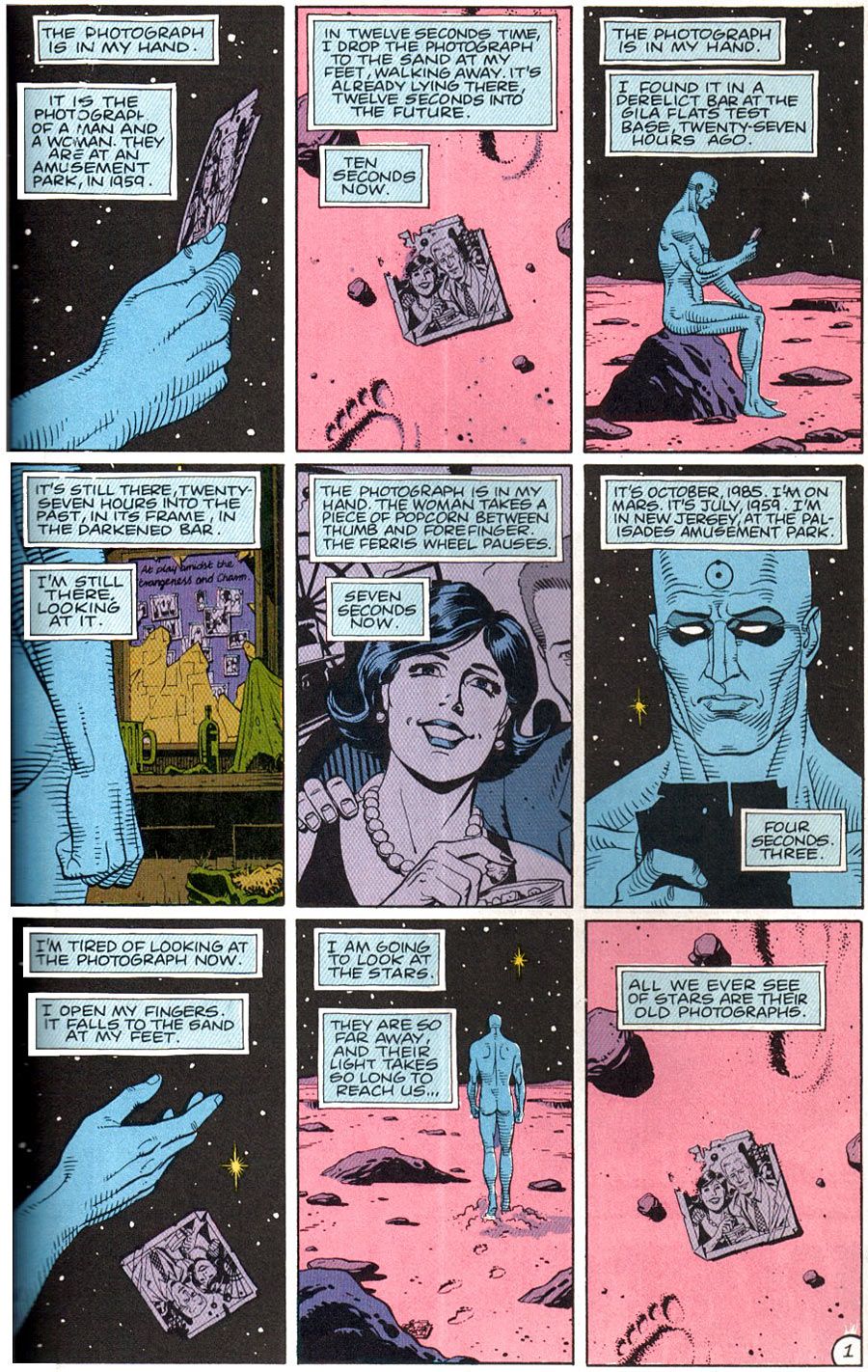

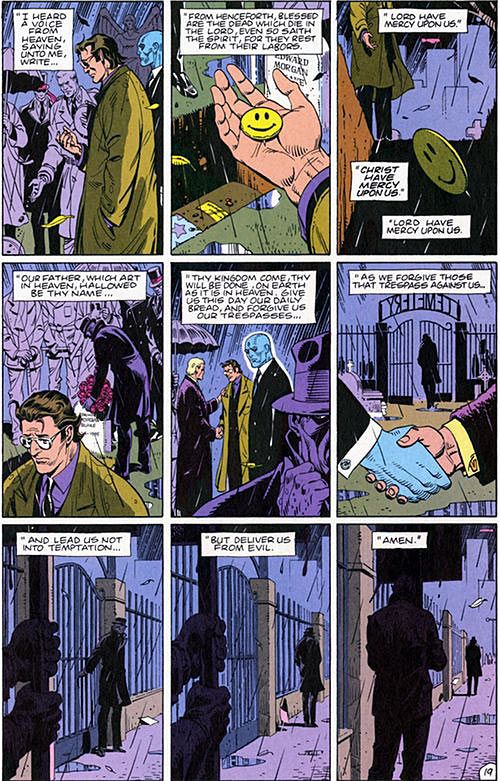

A page layout with repeated, same-size panels is called a "grid." Famously, "Watchmen" is based on a nine-panel grid format. "The Dark Knight Returns" utilizes a 16-panel grid.

Got all that? Good.

The most common element lacking in comic reviews is attention to the artistic side of the equation. Most reviews spend a cursory paragraph, or maybe just a few sentences, mentioning the art. I've certainly seen more than a few reviews that make no mention of the art or artists whatsoever, which is shameful.

To an extent, it's understandable, though absolutely not excusable. The vast majority of reviewers come to comics from a story-first perspective. I don't think it's unfair to say that a significant percentage of reviewers might well harbor dreams of one day writing comics. And there's nothing wrong with that... unless it skews the story/art balance in the review. Ideally, a comic review should be a 50/50 proposition, devoting equal space to discussing story and art.

Story and art are inextricably linked in a comic. One does not work without the other. This is a visual medium; the art is not pretty pictures, it's storytelling. There's just as much "writing" in the artwork as there is in the word balloons. Don't assume the writer is responsible for every story beat, especially visual beats. The writer and artist are co-authors, and the storytelling is a combination of their skills.

Writing about art is intimidating if you're not an artist, or at the very least, well versed in art and storytelling. But it's a job requirement to write about comics. Understand storytelling; do the visuals succeed in telling the story clearly? You should be able to look at the art in a comic, without dialogue, and have a fairly strong sense of what's happening in the story.

You don't have to be an artist to understand art. I can't draw at all, but I love art. I've educated myself in it, not just since I've been a pro, or even since I was simply a reader, but most of my adult life. A sense of comics history helps immensely. If you don't know who Alex Toth is, or why Will Eisner is important, or why Michael Golden is such a huge influence, learn those things.

Art taste is subjective, and an almost endless array of styles is present in contemporary comics. Style is a compilation of myriad choices: shape, form, value, line, rendering, exaggeration, negative space, and more. Is the anatomy consistent within the style, or is it simply poor draftsmanship? Is the perspective accurate or faked? You need not love an artist's style to appreciate its effectiveness in telling the story.

Reviewing comics is the quintessential "jack of all trades, master of none" pursuit. It's not necessary to be able to do any of the jobs on a creative team, but it is necessary to understand each of them.

The writer writes, most often in full-script format. The basic story and words on the page come from the writer (unless, of course, there's been editorial input on a work-for-hire gig, which is a determination you really never know). How that story is told is a combined effort by the writer and art team.

As comics move more and more to digital production, there's less division between the penciler and the inker. Increasingly, the line art is being produced by a single artist. But even so, it behooves a reviewer to understand the roles of both the penciler and inker.

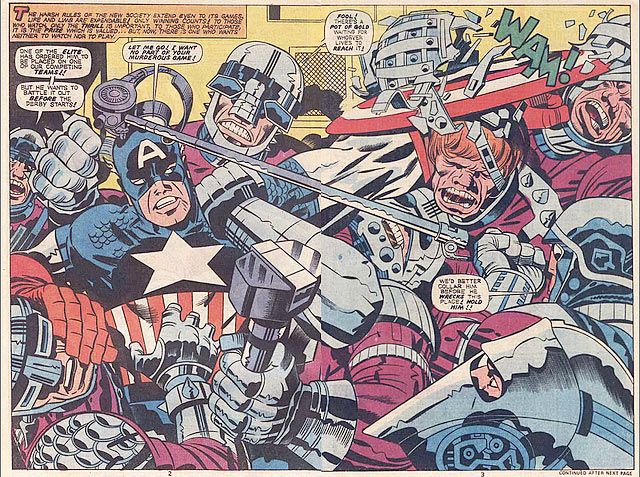

In the pencil stage, the artist is akin to a combined film director and cinematographer, choosing and executing the visuals that best tell the story. The inks refine and complete the black-and-white art, lending line weight, spotted blacks, depth, and texture. (Because it needs to be said: inks have nothing to do with color. I've seen reviews that credit the inker with color choices, I guess somehow assuming "colored inks" were used.)

The colorist's role is far more than simply adding color to black-and-white line art. Color is just as much of a storytelling device as line art, conveying mood and directing the reader's eye. The colorist's role has never been more essential in comics than it is now. A passing familiarity with color theory should be one of the tools in the reviewer's tool box.

The letterer's job is part of the graphic presentation of each page. In addition to basics like balloon placement, balloon shapes, fonts and display lettering/sound effects, the letterer is responsible (in concert with the writer's lettering script) for properly leading the reader's eye around the page. I constantly tell people putting together pages for comic pitches to get professional lettering. An otherwise professional comic can be ruined by amateur lettering, like an otherwise great cake can be ruined by awful icing.

As a creator, I deeply appreciate someone taking the time to review one of my comics. Reviews are useful to creators and publisher as marketing tools. That said, I think as a creator you have to take all reviews -- positive and negative -- with a grain of salt. If you're going to ignore the barbs of negative reviews, you have to ignore the praise of the positive ones. But reviews -- positive and negative -- that are written with a deeper understanding of comics, and the process of creating them, are a boon for everyone.

Ron Marz has been writing comics for two decades, and thinks it's pretty much the best job ever. His current work includes "Witchblade" and the graphic novel series "Ravine" for Top Cow, "The Protectors" for Athleta Comics, his creator-owned title, "Shinku," for Image, and Sunday-style strips "The Mucker" and "Korak" for Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. Follow him on Twitter (@ronmarz) and his website, www.ronmarz.com.