This week's release of "Sin City: A Dame to Kill For" -- the second film adaptation of the Dark Horse Comics crime noir series -- serves as a reminder that the works of Frank Miller still have a hold on pop culture. During his celebrated and often controversial career, Miller's work on "Daredevil" for Marvel, Batman for DC Comics and his creator-owned projects at various companies have had a profound impact on the comic book industry. His unique and unflinching sense of story and design helped move comics into the next millennium, and marked an age of new maturity for the medium.

In the past decade, Frank Miller has had a significant presence in Hollywood, with his creator-owned works adapted to the big screen, and the work he's done on licensed heroes informing billion-dollar franchises. Miller's modern comics work has been sparse as of late and the books that he has released have been very polarizing, but his legacy as one of the medium's most daring storytellers remains. With the next "Sin City" film now in theaters, here's a look at some of Miller's most memorable works.

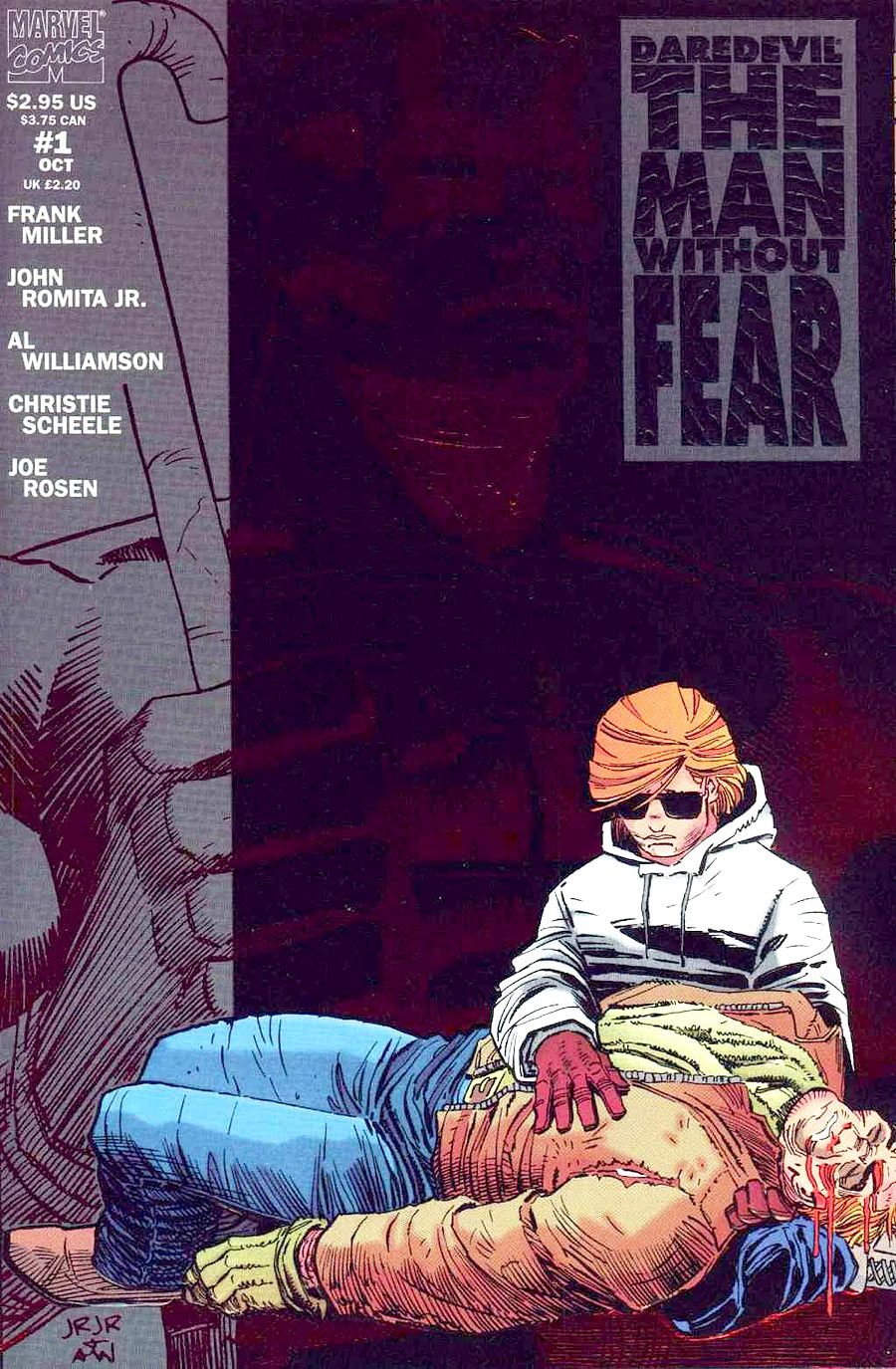

10. "Daredevil: The Man Without Fear" (Marvel Comics, 1993) with John Romita Jr.

In his '80s run on "Daredevil," Miller pretty much covered every vital aspect of the street-level hero, including his origins. In 1993, Miller revisited the character's early days in "The Man Without Fear." This series was essentially "Daredevil: Year One" -- a very exciting prospect for the many fans who fell in love with "Batman: Year One" -- and Miller, along with artist John Romita Jr., delivered. While not as historically significant as his "Batman" work, "Man Without Fear" stands as a testament to Miller's storytelling ability and can be considered the last example of "classic" Miller, as, after this series, his last long form work at Marvel, he focused on a more over the top, bombastic style of storytelling.

9. Ronin (DC Comics, 1983) with Lynn Varley

In the pages of "Daredevil," Miller perfected ninjas; in "Ronin," Miller went to the next level as he took all the martial arts tropes he mastered in mainstream comics and utilized them in a stunning, dystopian future. A reading and visual experience like none before it, "Ronin" was inspired by the research Miller did into martial arts films for his work on "Daredevil," and is the first project where the influence of manga was evident in his art style. The tale of a nameless samurai and his archenemies, trapped in a magic sword for eight centuries, "Ronin" follows what happens once they awake in a future only Miller could imagine. The book combines classic martial arts action and archetypes with a bleak sci-fi future in a genre mash-up that was way ahead of its time. In 1983, Miller was between runs on "Daredevil" and "Batman," two characters he would become synonymous with for decades, but "Ronin" was a harbinger of the Miller that would be an independent comics staple after he left the world of mainstream heroes behind. It stands as an experimental piece of comic book history where Miller challenged himself to deliver the book fans had no idea they wanted, a hardboiled, dirty, sci-fi, samurai epic that was part Philip K. Dick and part Akira Kurosawa.

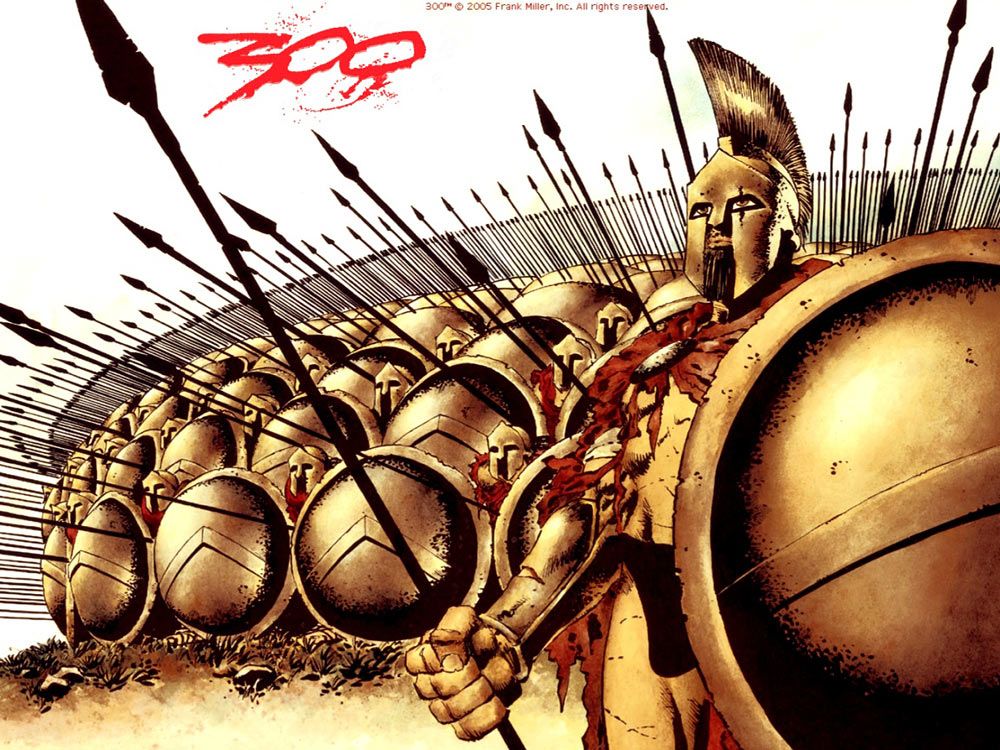

8. "300" (Dark Horse Comics, 1998) with Lynn Varley

Miller did ninjas. He did superheroes. He did more ninjas. He did dystopian futures, and he did noir, but nobody could have expected Miller's follow up to" Sin City." An exaggerated take on the Battle of Thermopylae, "300" was like nothing comic fans had seen before. Part historical fiction, part epic fantasy (dinosaurs and ninjas were not at the actual Battle of Thermopylae, at least as far as we know), part Robert E. Howard-inspired sword and sandal drama and part military fiction, "300" was a character-driven tale with a body count to shocked even the most jaded gore maven. The popular miniseries brought Miller's brand of unflinching storytelling from hardened, modern city streets to the world of ancient Sparta. His King Leonidas was the classic Miller hero, a stoic, squared-jawed man with a sense of decency and a propensity for explosive violence, and Miller rendered that violence in grand fashion as the project featured some of the most strikingly detailed art of Miller's career.

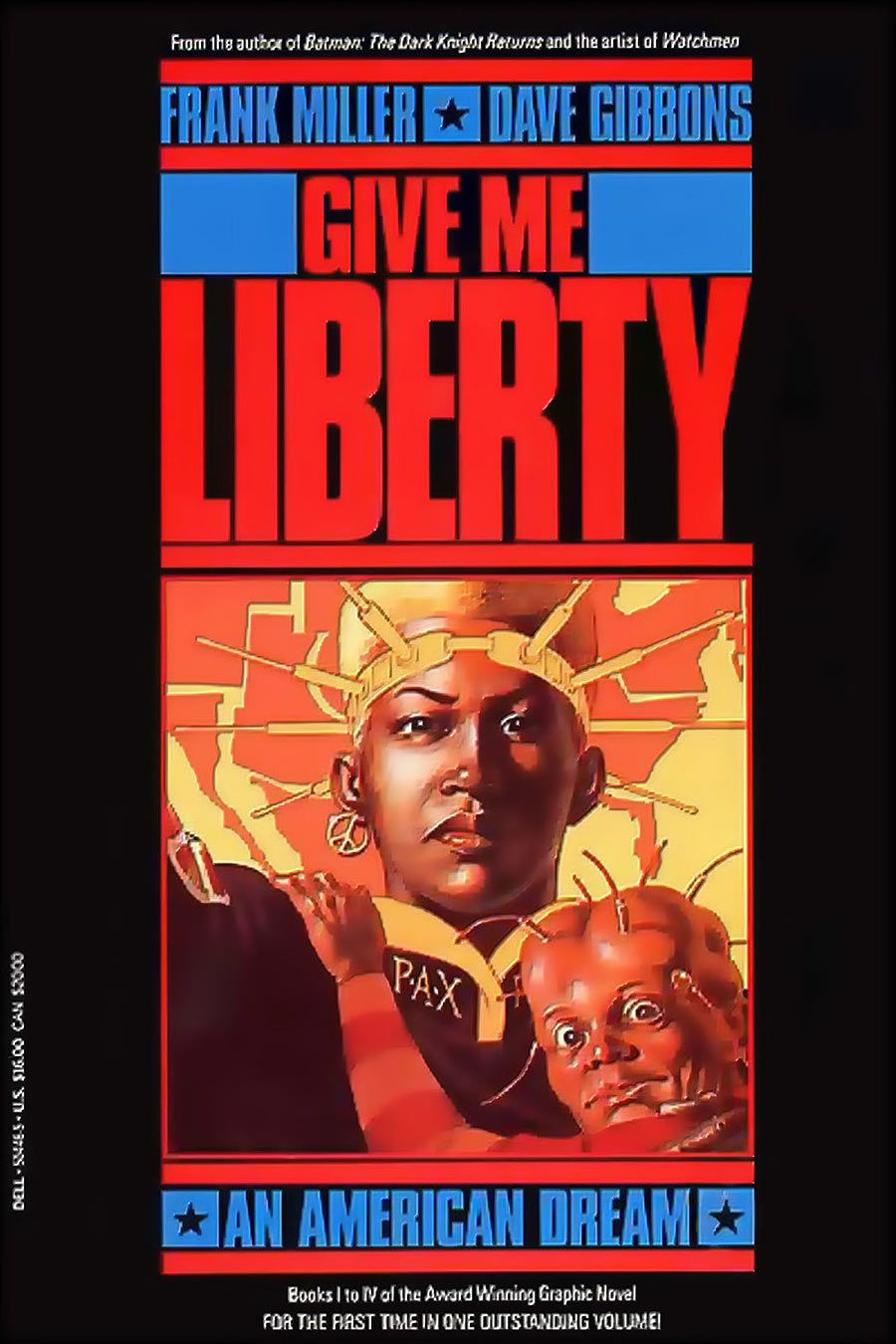

7. "Martha Washington" (Dark Horse, 1994-2007) with Dave Gibbons

In 1994, fandom, still in awe of his work on "Daredevil" and "Batman," waited to see what Frank Miller would do next, but no one could have suspected his next hero would be a protagonist like Martha Washington. Miller had already proven himself to be a master of the crime genre, so when it was announced that Miller and co-creator Dave Gibbons were teaming for a dystopian sci-fi tale starring a young black female protagonist, people were genuinely surprised. Washington's future was a hellish one, and like all good sci-fi, the story forced contemporary readers to look at their own culture and question the validity of modern reality's politics, business, war. Martha was a complex and relatable individual, widely regarded as one of Miller's greatest character creations. Through a series of miniseries, short stories and one-shots, readers followed Washington through her entire tumultuous life, until she received a heroic send-off in 1994's "Martha Washington Dies."

6. "Wolverine" (Marvel Comics, 1982) with Chris Claremont

It's hard to imagine a time when Wolverine did not have a book to call his own, much less five or six, but Frank Miller was the first artist to lend his talents to a Wolverine solo project, setting the standard for all who came after. Of course, it wasn't just Miller's depiction of Wolverine that made this series an artistic triumph; it was also his loving and breathtaking renderings of Japan and Japanese culture. The same way Miller's "Daredevil" and "Batman" narratively carried the characters for decades, Miller's Wolverine, a half-in control, half-feral warrior who carried the weight of his existence heavily on his shoulders, influenced the way in which subsequent artists would approach the character. And like many of Miller's great works, Miller's "Wolverine" was adopted by Hollywood as tone and visual structure of 2013's "The Wolverine" borrowed heavily from writer Chris Claremont and Miller's first solo tale for the character.

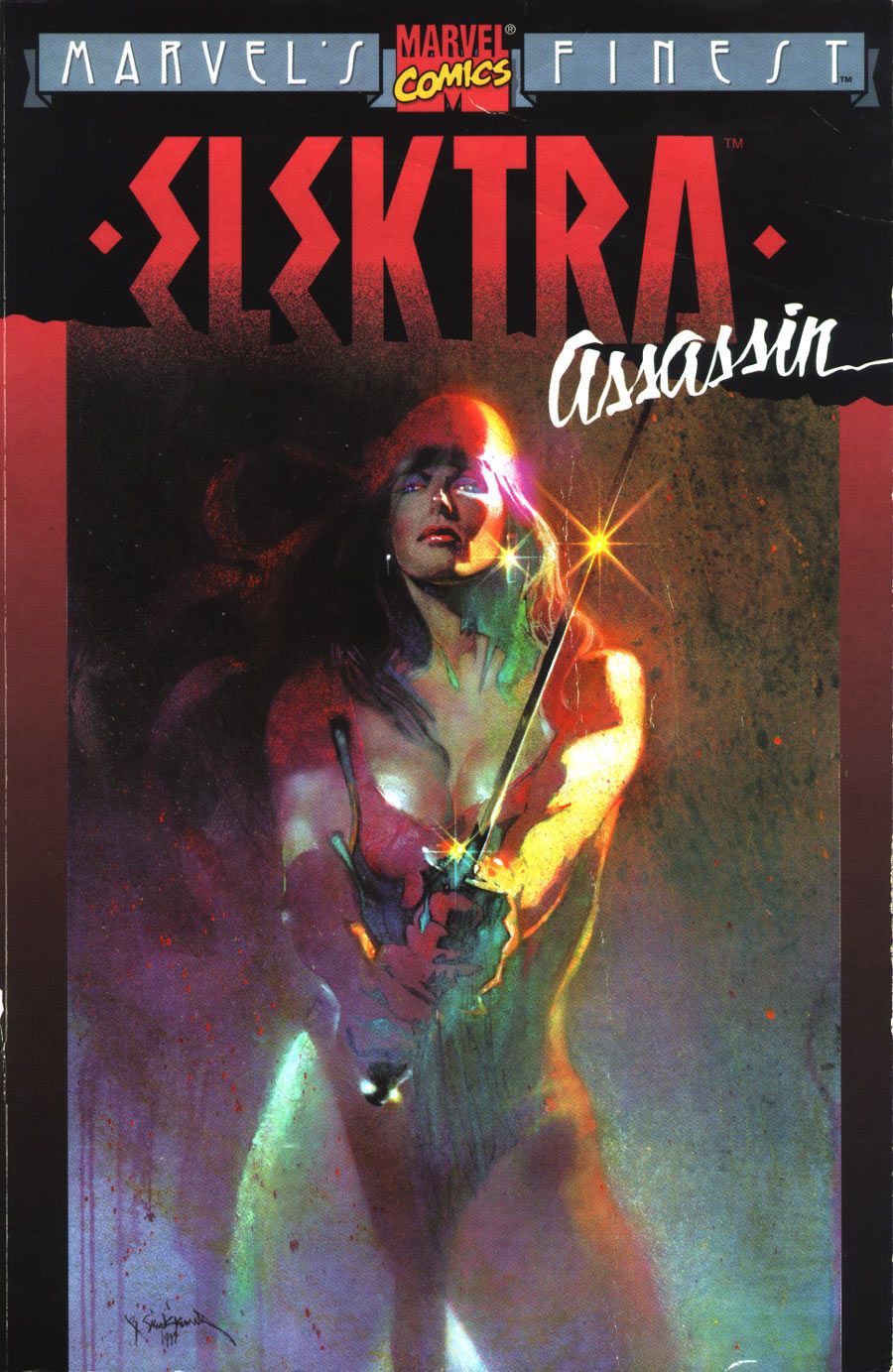

5. "The Death of Elektra" "Elektra Assassin" (Marvel/Epic, 1987) with Bill Sienkiewicz and "Elektra Lives Again" (Marvel/Epic) 1990 with Lynn Varley

Of all his creations, perhaps no character is more closely associated with Miller than Elektra. A femme-fatale assassin he introduced in the pages of "Daredevil," Elektra became such a huge part of Matt Murdock's world that fans were more than shocked when Miller killed the master assassin in the pages of "Daredevil" #181 (1982). The scene of Bullseye impaling Elektra on her one of her own sais was perhaps Miller's defining moment as a creative force unafraid to shatter reader expectations. After the death of Elektra at the hands of Bullseye, a character Miller raised from obscurity to arch-villain status, there was huge fan demand for her return. Miller wanted Elektra's death to stick, so he crafted the highly experimental flashback series (which some claim to be non-canonical) "Elektra: Assassin." Fully painted by Bill Sienkiewicz, the miniseries presented a non-linear tale of Elektra's past. With the assassin herself admitting that many of her memories are false, it's difficult to discern fantasy and reality in this fevered and often chilling tale of violence and pain. Like many of Miller's great works, the hallucinogenic origin story of Miller's signature character was a deconstruction of modern comic trends. Miller followed up the series in 1990 with the "Elektra Lives Again" graphic novel, a true resurrection of the character which he wrote and illustrated. Through these two works, Miller made it clear that though owned by Marvel, Elektra was really his character.

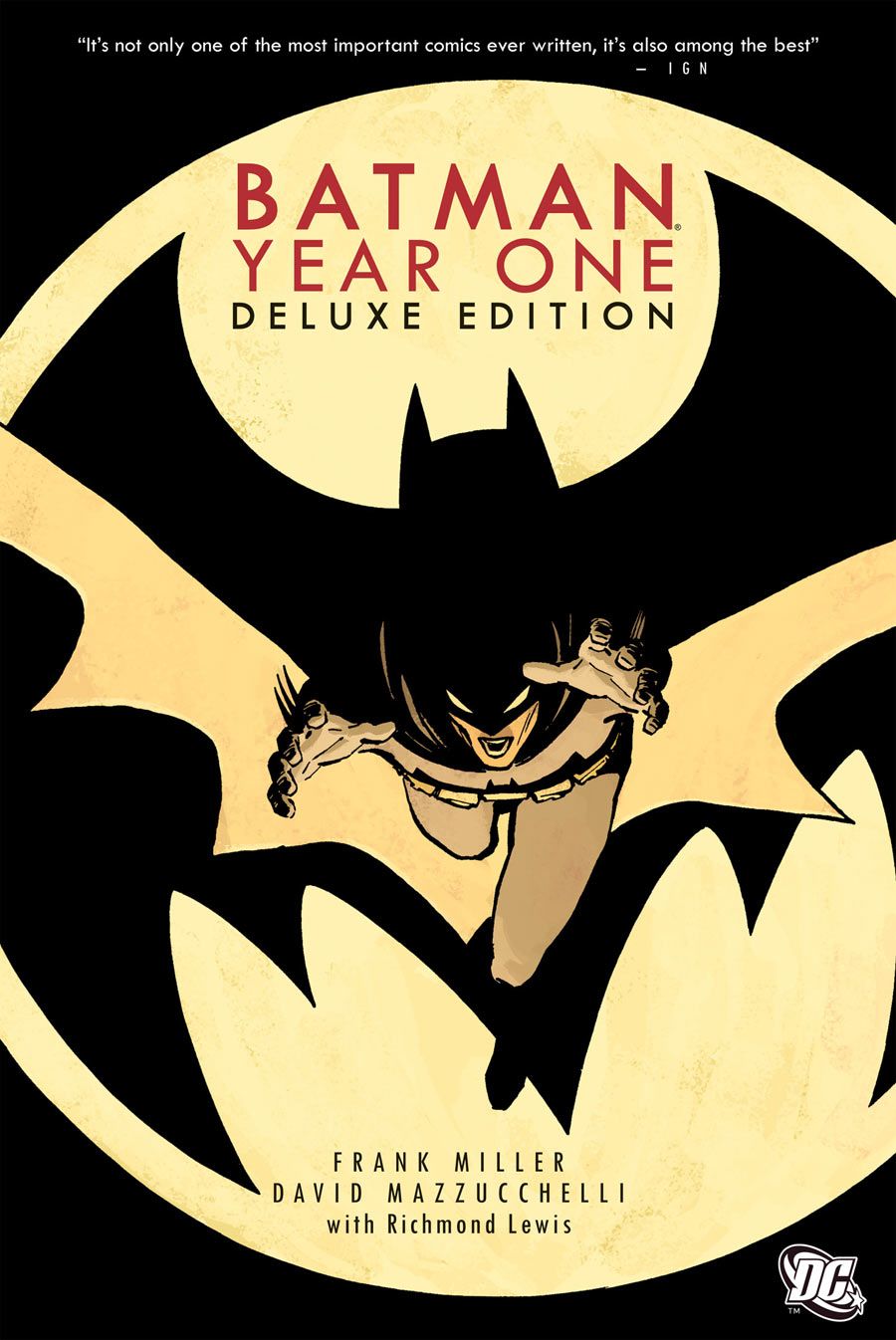

4. "Batman: Year One" (DC Comics, 1987) with David Mazzucchelli

Miller already changed the character forever with "The Dark Knight Returns," but in "Batman: Year One," Miller and his "Daredevil: Born Again" partner David Mazzucchelli got to play with an in-continuity Batman and his cast, retelling the iconic character's origins in the present day. Taking Batman all the way back to his roots, to the days of Bill Finger and Bob Kane, Miller again rediscovered the essence of Batman and Gotham City, giving fans the definitive origin of Bruce Wayne. In 1987, DC was a year removed from "Crisis on Infinite Earths" and its rebooted continuity. The company turned to Miller to work the same magic had a year previously with "Dark Knight Returns," and boy, did he deliver. How definitive was this revamped origin? With a single story arc, Miller defined the post-Crisis Batman and gave DC a version of his origin that would carry the character for decades.

3. "Sin City" (Dark Horse Comics, 1992-1999)

"Sin City" has now been the subject of two feature films, but it all began in the pages of the anthology series "Dark Horse Comics Presents." "Sin City" was one of Miller's first major projects away from Marvel and DC, and it was the first time fans got pure, unfiltered, raw Miller as he presented a noir thriller that refused to pull punches. In addition to redefining Miller once again, "Sin City" helped put Dark Horse on the map as a place to go for brave, genre defying fiction. Many times during the course of "Sin City," Miller had his tongue firmly in his cheek, presenting an over the top violent world where women wear swastikas as bras (a Miller trope first seen in "The Dark Knight Returns") and everyone talks like a Raymond Chandler novel with the volume turned to eleven. It all worked, and two films later, people remain intrigued with the world of "Sin City."

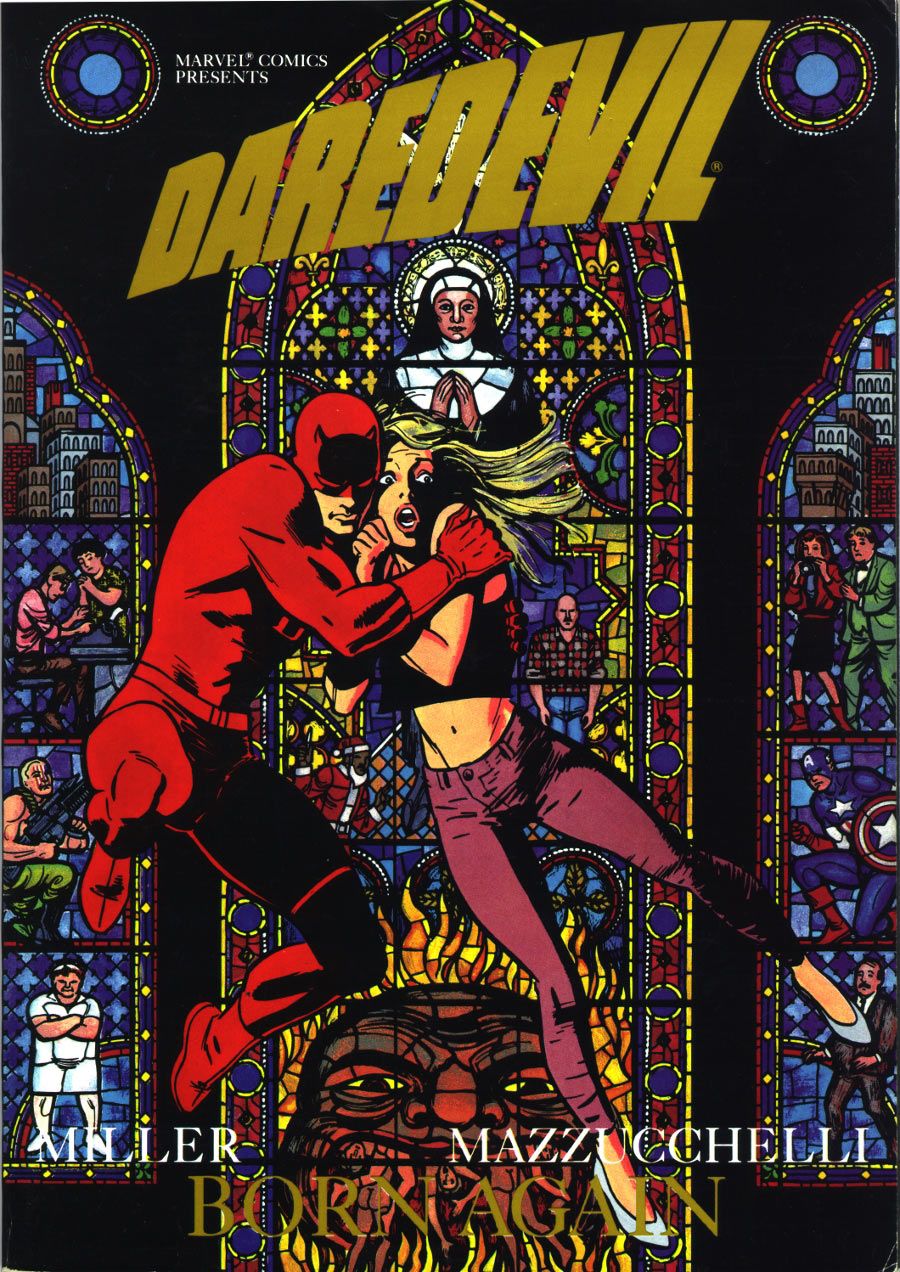

2. "Daredevil: Born Again" (Marvel, 1986) with David Mazzucchelli

It seems there hasn't been a Daredevil story since "Born Again" that hasn't borrowed something from Miller's magnum opus, which shook the character to his very foundations. The story was a figurative descent into Hell as Miller took Matt Murdock beyond the breaking point and back, and when the smoke cleared, Daredevil was a greater hero than ever before.

The whole thing started with the betrayal of one of Daredevil's oldest supporting characters, his true love, Karen Page, whose heroin addiction drove her to sell Murdock's secrets to the Kingpin for the price of a fix. Marvel was built on Stan Lee's idea of the illusion of change, but in "Born Again," Miller brought real change to one of the publisher's core heroes. The book's entire cast found themselves tainted by corruption, the Kingpin was more manipulative and evil than ever before, and no Marvel hero had ever faced a greater crisis of faith than Daredevil throughout the arc. "Born Again" also established Daredevil as one of the few openly religious heroes in the superhero pantheon, making Catholicism a core part of Matt Murdock's character. If all that wasn't enough, Miller also introduced the villain Nuke, a condemnation of Reagan-era America by way of a forgotten and mistreated Vietnam war veteran. Miller and artist David Mazzucchelli's take on the hero's journey, "Born Again" immediately became the standard to which all "Daredevil" stories would forever be held.

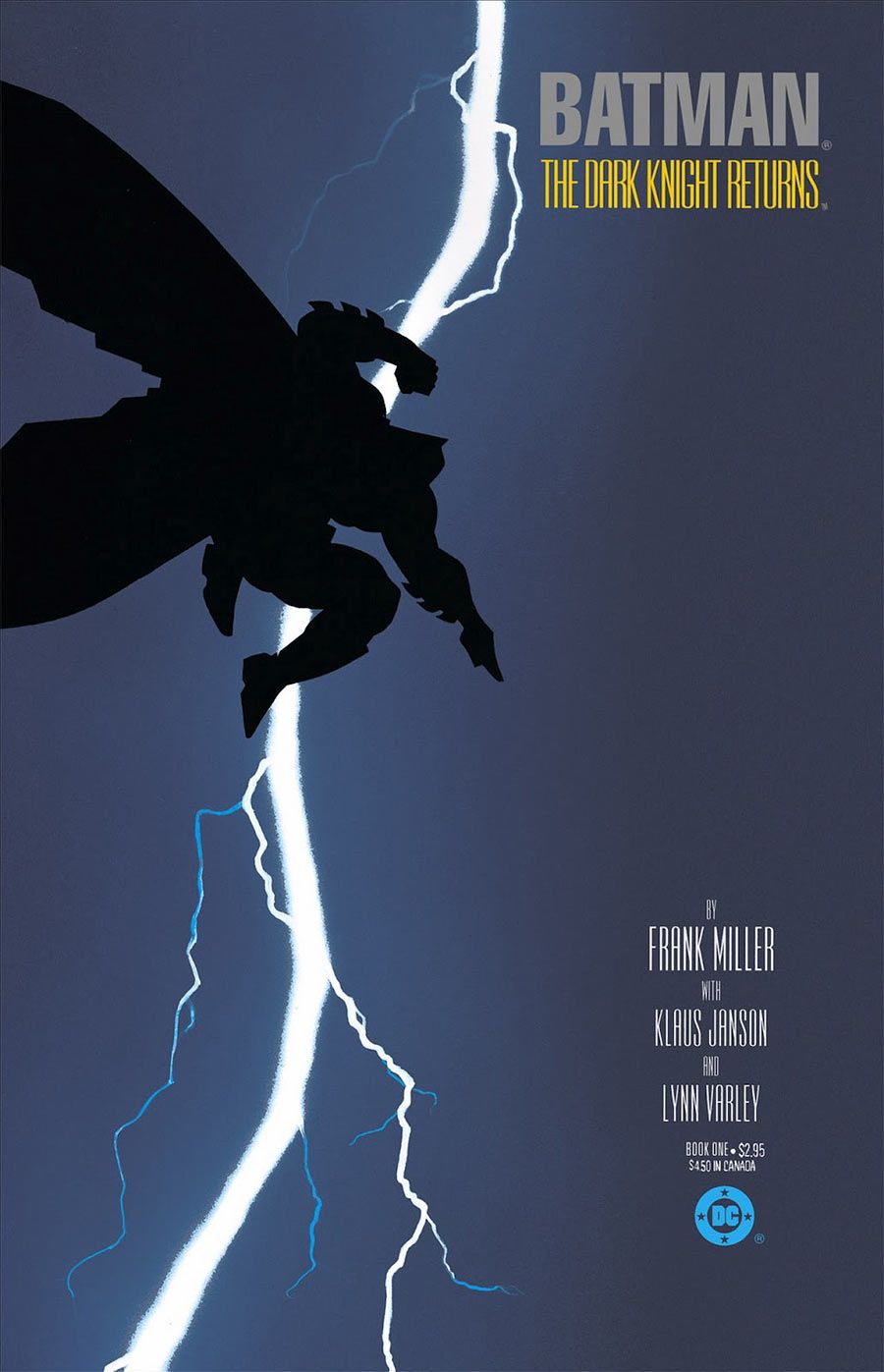

1. "The Dark Knight Returns" (DC Comics, 1986) with Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley

Outside of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' "Watchmen," it's hard to imagine a more influential superhero comic than "The Dark Knight Returns." In the opening pages of this seminal work, Miller introduced unsuspecting comics fans a very bleak future, one without a Batman. What followed was a heroic rebirth for the iconic hero, and one of the greatest genre deconstructions in modern comics. When "The Dark Knight Returns" debuted, the Adam West "Batman" was regularly shown in syndicated reruns and "Super Friends" was still a Saturday morning cartoon staple. Superheroes were viewed by the general public as disposable and childish, and while Denny O'Neil, Neal Adams, Len Wein, Steve Englehart, Marshall Rogers and more had been presenting a very dark, mature take on Batman for years, superheroes and the stories that featured them were still not viewed as a legitimate form of literature nor a viable storytelling medium.

Frank Miller's future-Batman tale was one of a handful of comics that changed all that. With "Dark Knight Returns," Miller, along with inker Klaus Janson and longtime colorist Lynn Varley presented a story that was part modern political satire and part loving tribute to the history of the character. It was fine art and as it turned out, the perfect way to reinvent Batman for the new age of comics, redefining the Joker and Two-Face, and forever altering the relationship of the World's Finest heroes, Batman and Superman. Director Zack Snyder's "Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice" looks like it borrows many visual cues from Miller's work, and it will be interesting to see how much of the conflict between the two heroes in the film also takes on. Many artists and writers have worked on Batman, but Miller is one of the few that can claim he changed one of comic book's greatest icons forever.