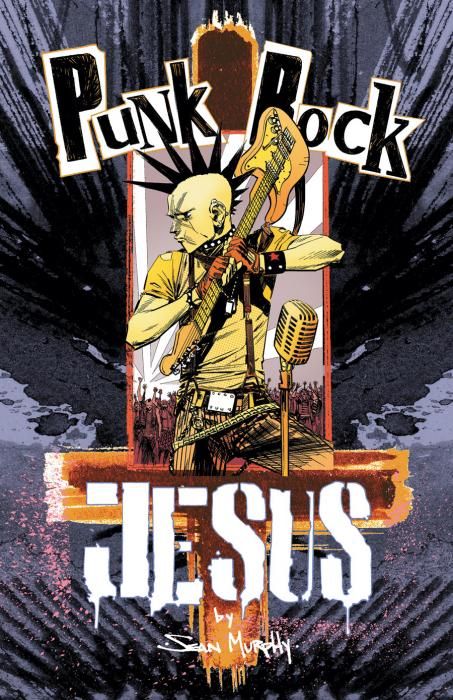

"Punk Rock Jesus" #4 by writer and artist Sean Murphy is right past the halfway point for the 6-issue miniseries, and appropriately, this is the issue where Punk Rock finds Jesus and vice versa. Young Chris, clone of Jesus Christ, grows into a teenager in this issue, and like many teenagers, fictional or real, he experiences a traumatic coming-of-age. Holden Caulfield, Adrian Mole and numerous other disaffected, disenchanted young boys-to-men have nothing on Chris when it comes to facing a true ordeal. Like both his namesake and punk rock, Chris is shaped by rebellion against the established order of his time.

Murphy is an unpredictable storyteller, and it's stunning how much action and rich detail he packs into only thirty-two pages. The heart of the story is Chris. A sweet kid up until this issue, Chris begins to go willfully "out of control" in response to the machinations of his jailer and Big Brother-like manager Rick Slate. Chris changes alarmingly and rapidly in this issue, but his transformation is realistic, especially for a teenager. The iconography and Chris' words on the last page feel inevitable yet still subversive.

Murphy is earnestly, even mercilessly political, "Punk Rock Jesus" is directly critical of organized religion, reality TV, celebrity journalism, the military state and a host of other American sins, but Murphy manages not to be too talky or over-didactic, since he relies on characters, particularly Chris, to make his points. With Chris and Gwen as the victims to absorb all our sins, Murphy counts the cost of the TV-watching public's passive consumption of reality TV's backstage-edited, manufactured lives. It is ironic that Murphy uses punk rock, itself no stranger to spectacle, to counter the hunger for another kind of spectacle.

Thomas the ex-IRA soldier gets a large chunk of "Punk Rock Jesus" #4 to himself. His section of the tale includes a flashback, and Thomas' formative years are strangely even more tragic than Chris' terrible childhood. Murphy's dialogue here is particularly strong. Thomas is a man of few words but the pathos in those words and in all the silence is fierce. Thomas is no saint, but his terrible need to prove himself, his quest for moral clarity, his strength and his desire for atonement are so intense that he often threatens to steal the spotlight from Chris. They are fragile foils of each other, the innocent child of God and the large man with blood on his hands, and their side-by-side development as men makes for a fascinating literary juxtaposition. The contrast of the IRA's methods of rebellion vs. those of punk rock lingers in the background, haunting the reader with questions about independence and different paths out of oppression.

Murphy's fine line, textured backgrounds and liberal shadows define the mood of the series. In "Punk Rock Jesus" #4, Murphy is adept in conveying information through body language and facial expressions, and he also frames Gwen's assault on J2 in such a way that the reader knows details about Rick Slate's actions that characters within the scene can't see. Murphy's outdoes himself in the detail of Chris' room, which is a pictorial syllabus, a Murphy-curated library for the new Jesus: Iggy, Fugazi, The Clash as well as Charles Darwin, Thomas Jefferson, Jared Diamond and Carl Sagan. Perishing of being consumed by others, Chris turns to consuming punk rock, sociological critique and science, which open a way for him before he sets himself free, a mental liberation before the physical one, mind before body.

In "Punk Rock Jesus," Sean Murphy is constructing a big, multifaceted story, a philosophical and political meditation on the uses and abuses of organized religion, touching also on themes of childhood and adolescence, grief, crime and redemption, purity and pollution, freedom and tyranny, conformity and rebellion, spectacle and consumption. Not only does "Punk Rock Jesus" #4 dare to dream, but it succeeds in its ambitions.