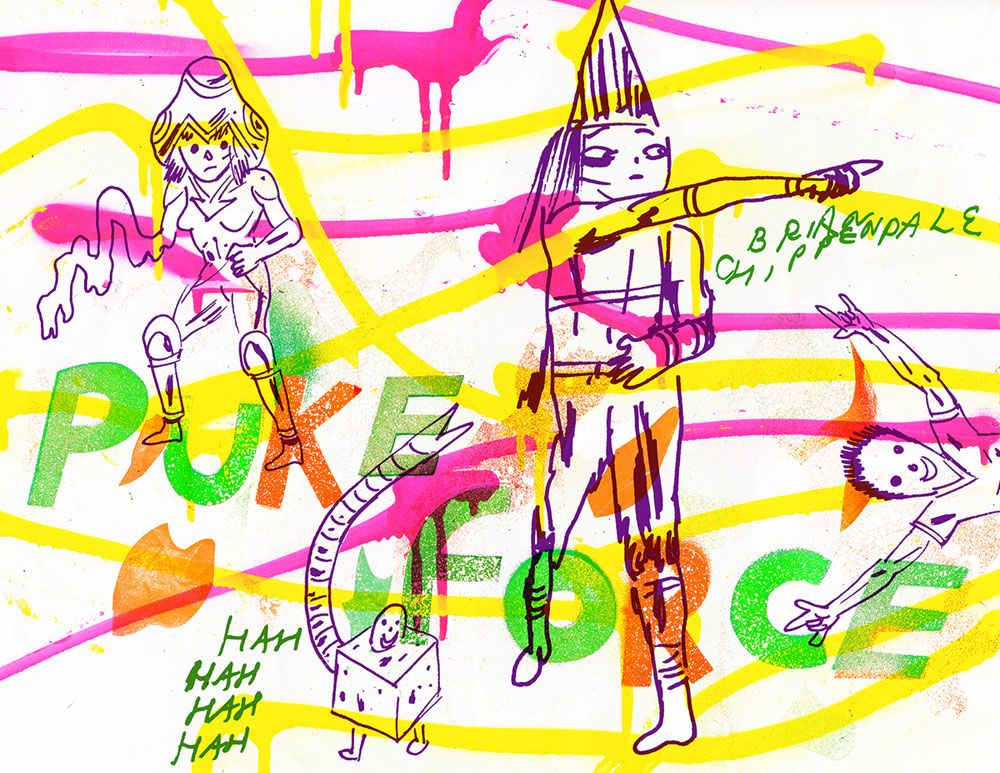

Brian Chippendale has two careers. He's both the drummer and vocalist for the band Lightning Bolt, and he's the creator of a series of graphic novels including "Ninja," "Maggots" and "If n Oof." In both his music and comics, there's a raw immediacy, an approach to his art that continues in his most recent project, "Puke Force."

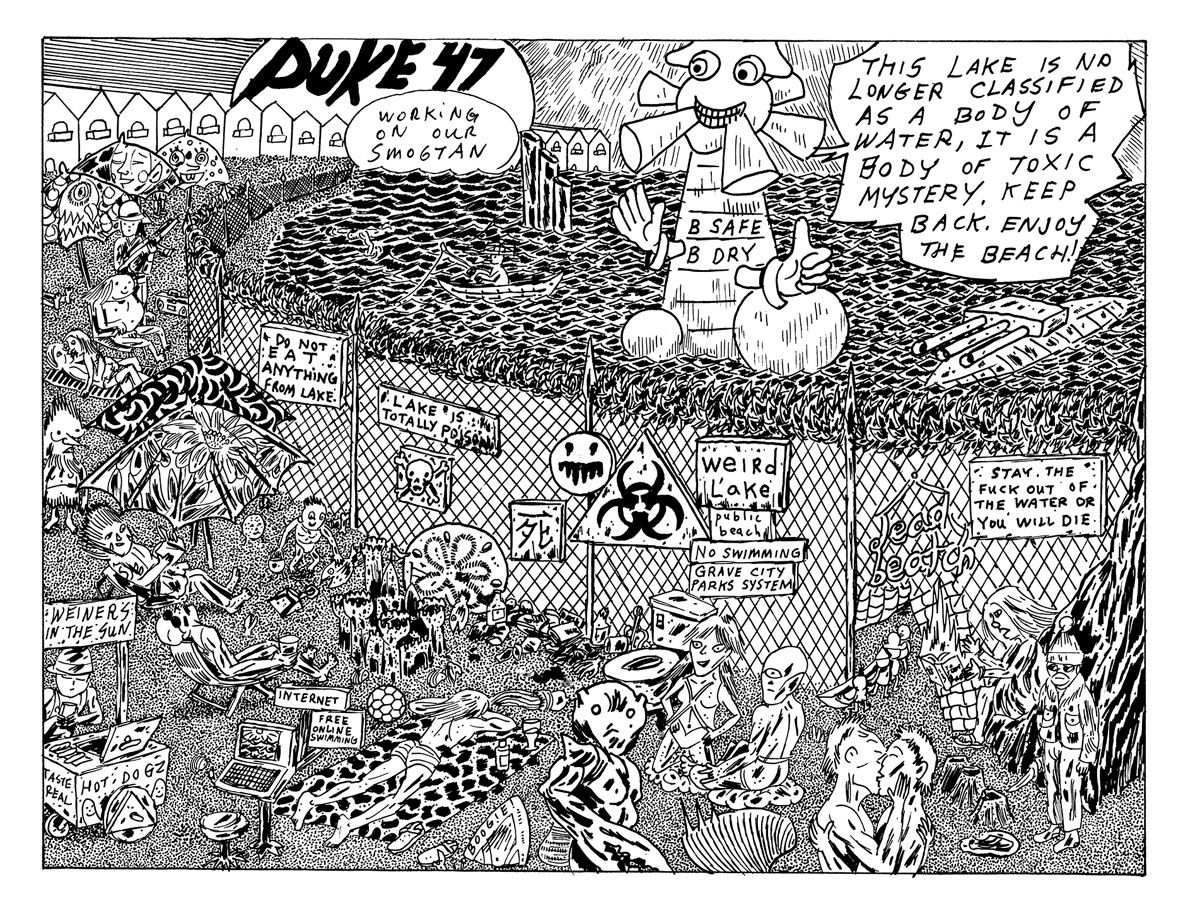

Available now via Drawn & Quarterly, "Puke Force" is political and satirical, weird and a lot of fun. Described by its creator as being "about side roads, about going somewhere, but not actually getting there... getting somewhere else instead," the graphic novel needs to be read in order to be fully understood. And even then, you might still have difficulty summarizing it -- and that's just how Chippendale intended it to be.

CBR News: Where did the idea for "Puke Force" originate?

Brian Chippendale: It's a sequel of sorts to a previous book named "Ninja." "Puke Force" takes place in the same town, with some of the same characters. "Ninja" was a book that collected comics I drew when I was 11, about a ninja, and more "Ninja" comics I drew 18 years later which, for the most part, are not about a ninja; they are about a town and the weirdos who lived there. The name "Puke Force" is the name of the power one of the characters has: A.W. Dude, or All Wrong Dude, has the ability to puke on people and melt them.

I remember the strips that were on the Picturebox website years ago. Did you always know it was this much longer story, or were those originally intended to be a separate shorter piece?

I'm generally pretty certain that when I start something, it will probably expand exponentially. That's really why I do things, to see where and how far they will go.

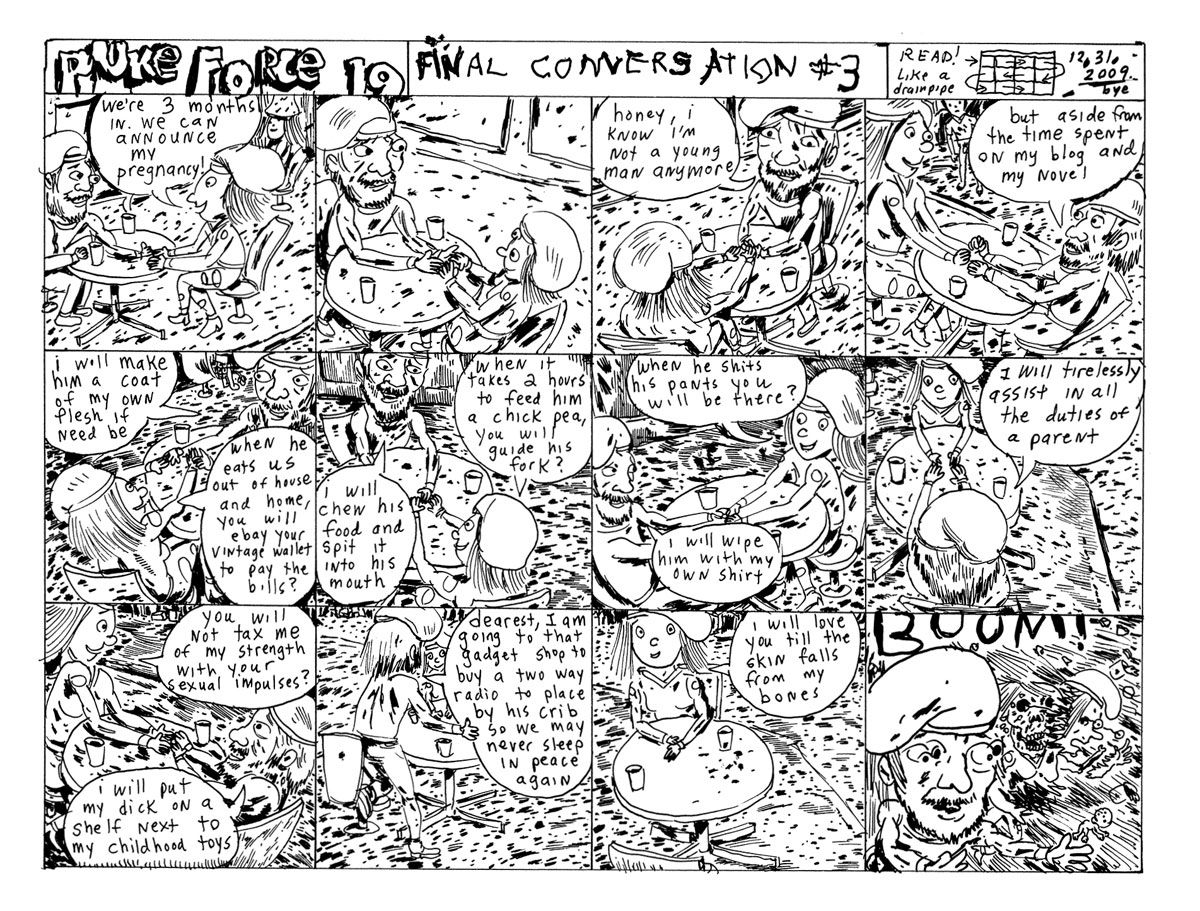

We're supposed to read the strips in an unusual way; why did you decide to design the page in that manner?

I've been doing comics like that for years. Snake-style or "Chutes and Ladders"-style. My older comics are much more about movement, and the panels were more like animation stills. I didn't like the idea of your eye leaving the panel progression at any time to skip down to the beginning of the next row of panels, because it interrupted the flow of motion. That's the impetus: never allow the reader to escape the page.

Were comic strips and weekly comics a big influence on you?

I never really thought of them as an influence. I've read a ridiculous amount of Marvel super hero comics, so I would think that influence would outweigh anything from "Garfield" or "Bloom County." But I read those strips as a kid pretty religiously every Sunday, and the "Puke Force" comics are a continuation of "Ninja," which was the same kind of newspaper strip format. And again, the initial pages for that I drew when I was 11, so the page structure for "Puke Force" goes way back to a time when maybe newspaper comics held a greater power over me than comic books.

I keep trying and failing to describe the book in a condensed way. How do you talk about it?

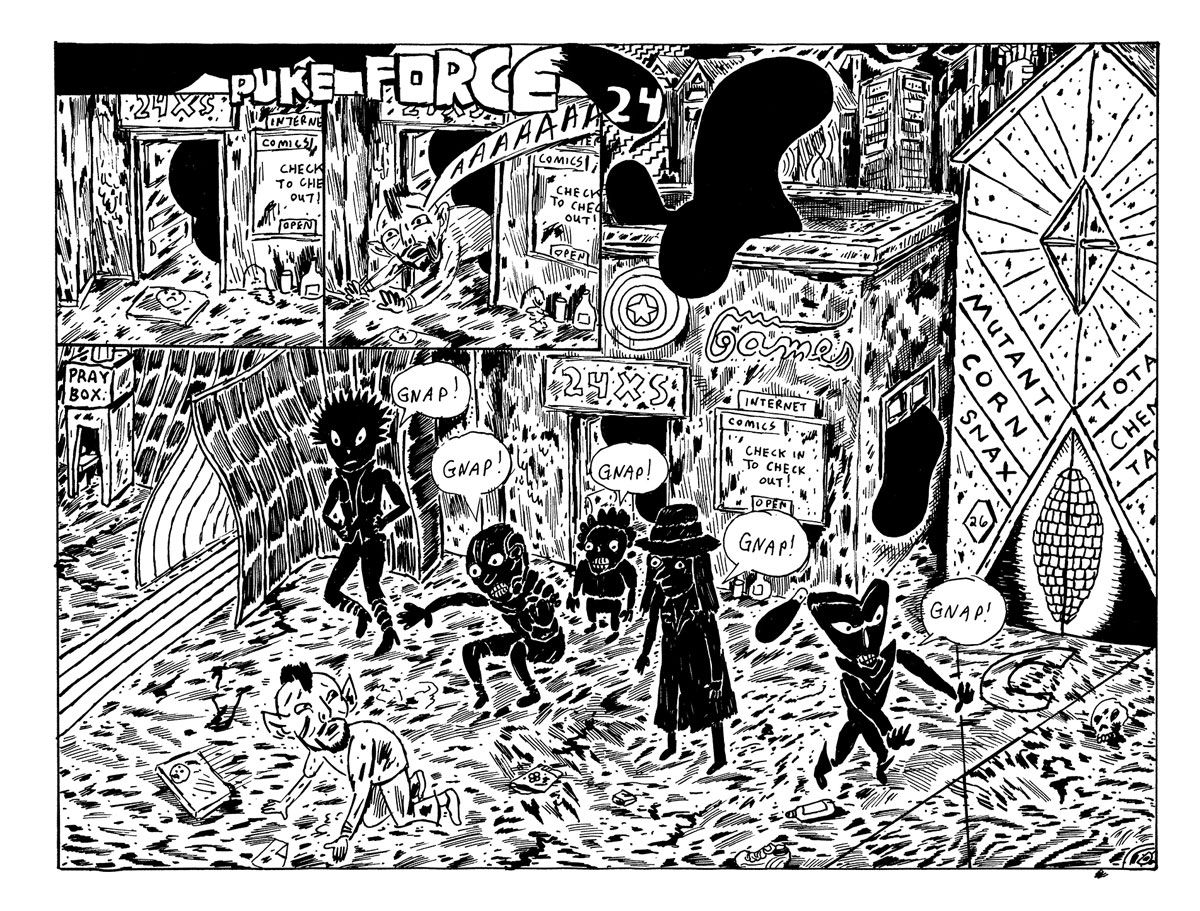

I talk about it for great lengths of time, and I don't really condense it! But you kind of can: it's a slice of life from a town over a short time period that involves a pretty large cast, all of whom are somehow connected and all of whom are encountering something somewhat sinister. A collision of humans and technology is involved, a sort of "data out of control" narrative. Kind of. But it's really about side roads, about going somewhere, but not actually getting there. Getting somewhere else instead.

One aspect that obsessed me -- and I feel like it did you as well -- is that on one level, the story is about a bombing, it's about surveillance. But then you go off on these small tangents, the backstories of these characters and these small moments. You don't want to make a book just about small moments, but you know that they're important.

The book, for me, is really just a following of energy, my personal creative energy. Each story starts maybe as a personal moment, but sometimes they kind of catch fire and more stories pour out of me. I just follow 'til it's interrupted.

The cafe bombing was a part that begged a little more attention. There's also a bar scene that flowed really freely, and then a 10-part story of a kid growing up with fucked up parents and how he reacts to that. There's not a ton of logic as to why certain stories took off and others were just snippets; it really comes down to me being busy and having other occupations that take me away from comics, so I get done what I get done in certain phases. When I return to it 6 months later, I generally have new concerns that I want to explore.

I could craft the whole thing in a more simple way, stick to a theme, but why bother, really? "Puke Force" has got to stay fun; that's why I do it, and the consistency of it comes from the drawing and the format, not necessarily its concise plot. It all comes together in its own way. What is a story anyway? What makes a book? It's just some pages stuck between a front and back cover. Obviously, there are certain things you can do to assure yourself a safe, final product, like the rules of a 3-and-a-half minute pop song or whatever. Or you say, "Fuck it, I'm just going to make this, or let this make itself." It's idea bombardment. Each page has a reason to exist, there is a story, sometimes very simple, per page. And there is a narrative arc that weaves in and out at various times. It ends with a bang. It's a book.

How big an influence is TV? There are a lot of shows now that want to tell big stories with a lot of action and violence, but also pause and tell these small stories and side stories that really add to it.

I was a huge "Lost" fan (of course, except Season 6). I think "Lost" affected me on a lot of levels, consciously or not. I don't read a lot of indie comics, so they aren't really an influence unless they're older. People like Gary Panter are there, in the line and the designs, but I was sort of on that track before I really became aware of him. Old school Jack Kirby is buried in the designs, or I hope it is, a little.

But, yeah, the way things unfold, I guess is fairly similar to these current TV dramas. But also older shows like "Moonlighting." (Is there anyone left alive who watched "Moonlighting?") Like a sitcom that seems really light and frivolous, but suddenly a larger, darker, sadder arc appears and ties it up, ruins the show. But I liked it anyway. On one indie level, funny enough, old Drawn & Quarterly comics are probably an influence as well. Old Julie Doucet "Dirty Plottes," or old Chester Brown, when he was more random. Life gets random. I try not to deny it.

When you're creating something with a lot of these contemporary issues, and you can turn on the news before or after and see a lot of this, is making the book cathartic? Or do you even think of it in those terms? Is it just that we all live -- whether we admit it or not -- at the intersection of all these concerns and obsessions?

I don't think it's necessarily cathartic. Maybe I'm spoiled because I play drums in a pretty wild band and those shows are definitely cathartic, so I'm not sure if releasing books can compare. The release of "Puke Force" feels OK because it is political. Certain aspects of politics do change quickly, so you want your satire to come out when it's still relevant. But luckily, or unluckily, divisiveness and paranoia has only been increasing since I started "Puke Force," so I'm still pretty on target.

I think we all do live with all these concerns and obsessions, and as an artist, I take time to dig them out and work with them, make connections. Excavating internal garbage, that's the job. I don't think making these comics necessarily answers any questions I have about issues, or problems I have or society in general, but it's good fuel to scratch the creative itch. I really just like to organize things. I think a lot of artists do. You just have to find the pile of shit you want to organize and go at it. It's selfish. There's also some, "just wait 'til people read this and see the issue this way" urges, but at the end of the day, I am for the most part preaching to the choir, so I have to just take pleasure in the making.

I'm not converting many haters. Haters of comics, or ideas like mine probably can't even figure my damn personal mark-making language out, let alone find the plot. I'm laughing at you, not with you.

Do you keep a sketchbook? Do you draw a lot?

I have piles of drawings. I draw virtually every day, or I try to. Just raw, random sketching. That's where most "Puke Force" ideas come from. Free drawing is key. Trying to push the hand into new territory. Either accompanied by talk radio, music or whatever incidental sound, free drawing is the foundation.

I ask that to get at your process a little. When you started, did you know what the story was, the shape of it, or were you working out the story and how to end it as you worked?

When I started this, I had no idea what it was or would be. Maybe halfway through, a few endings started to formulate, but the path to those endings was still very unclear. And I like that. Surprises can still happen. In the beginning, and even deep into the process, I try to go down whatever path is the most exciting to keep the work moving. If you're stuck on writing, just free draw. If you're stuck on drawing, well, keep drawing. But I don't set the bar very high in the beginning, because I don't want to paralyze myself. Once things are flowing smoothly, I think it's OK to raise the goal post a little higher. It seems to me, many creators' -- or would-be creators' -- biggest problem is getting started. So I make getting started really, really easy. Like, no real goals on Day One. And if I hit a wall, I try to joke my way around it.