THE MISSION is a weekly column spotlighting diversity in comic books, graphic novels, and popular entertainment.

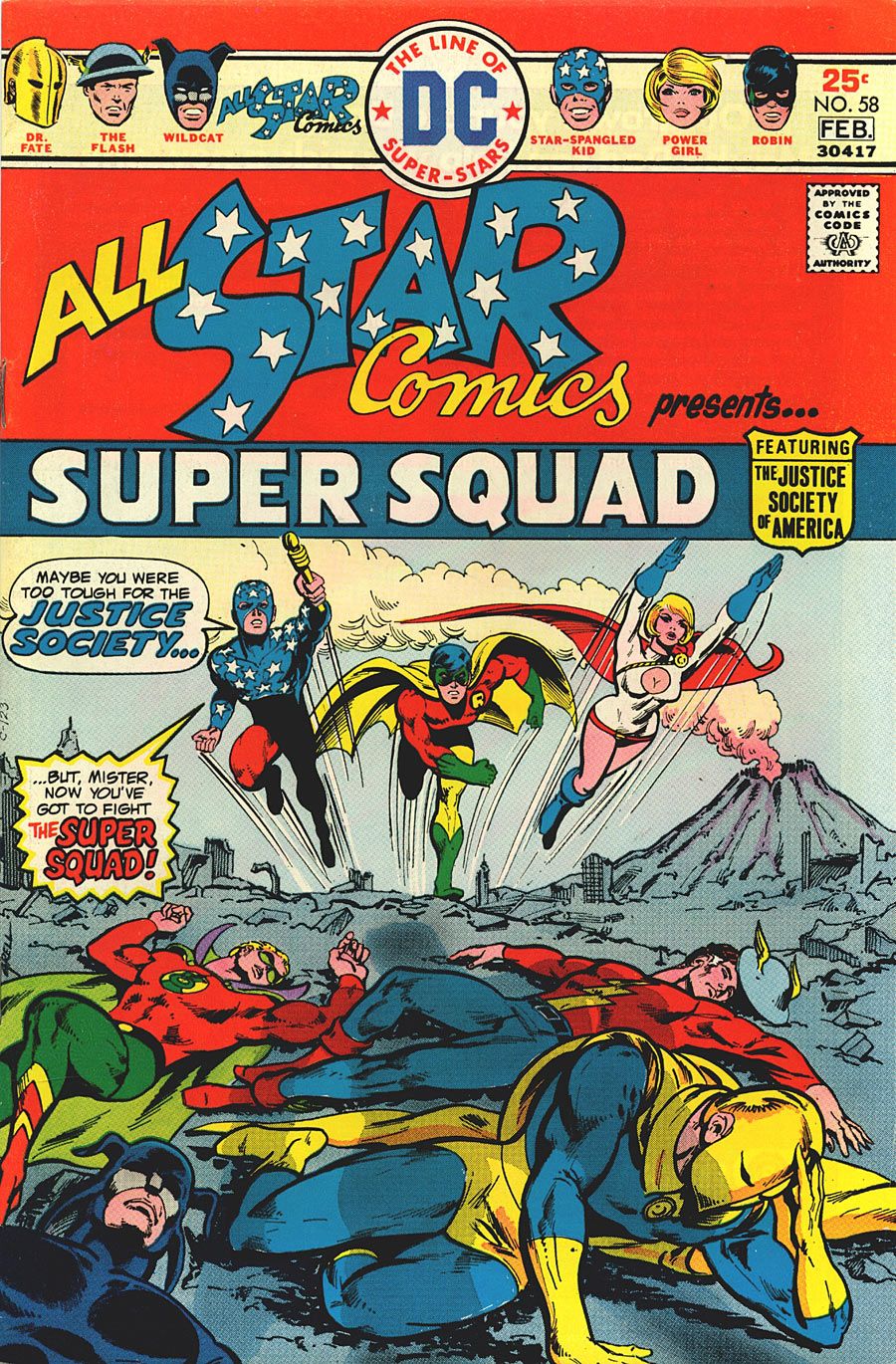

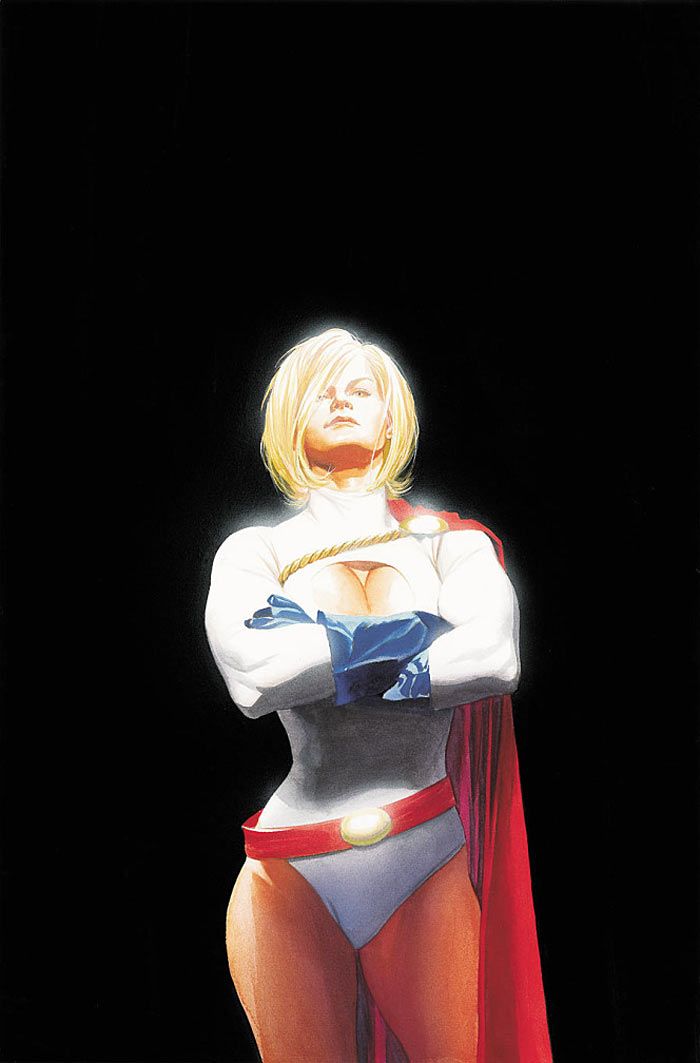

Power Girl, a character introduced in 1976 in "All-Star Comics" #58, is the kind of character that gets a lot of love from the fan community for various reasons.

My first exposure to her was as a boy who was a DC head in the second and third grades. I discovered the X-Men in the fourth grade, and my life was changed forever... but that's another column.

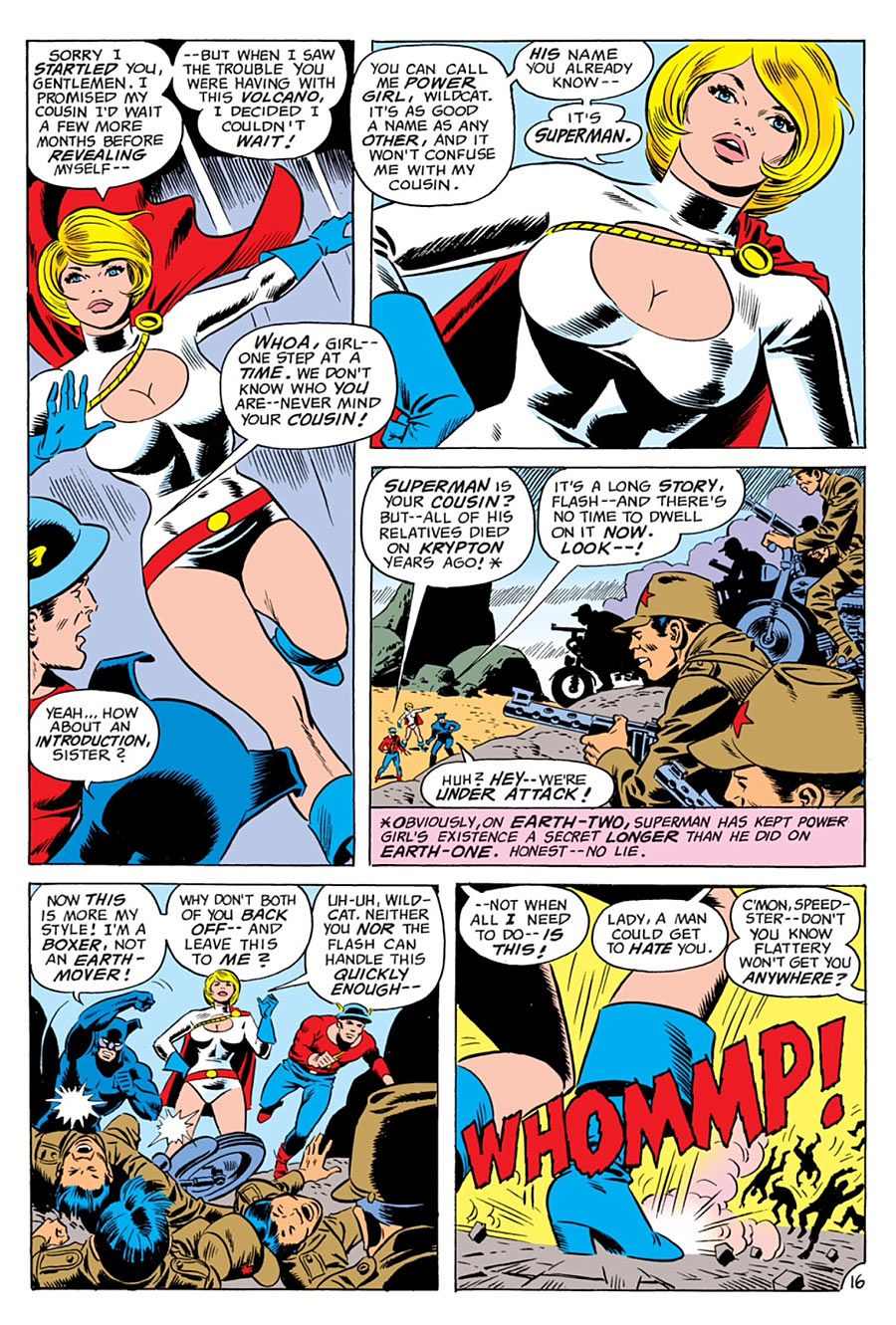

So Power Girl was a DC Comics sensation in the '70s, an alternate Earth cousin of Superman, but unlike Superman she did not have an "S" on her chest.

She had a big hole, and big breasts.

Did that endowed part of her body require ventilation?

Why were her breasts so big?

What did the combination of large breasts and a hole in her costume highlighting them mean, in terms of her character? We knew what Batman's bat meant, and Superman's "S," and Green Lantern's lantern, but Power Girl's hole remained a mystery.

Decades later, I worked for DC Comics as an Editor for the Batman line of comics, and I was fortunate to edit the title "Birds of Prey," a female-led action adventure series full on intrigue and great characterization. The series starred Barbara Gordon, the wheelchair-bound mission controller known as "Oracle," and Dinah Lance, the on-site crime fighter known as "Black Canary."

Chuck Dixon, the founding writer of "Birds of Prey," established that Oracle's first partner was not Black Canary, but was in fact Power Girl. Something terrible happened, and a mysterious event ended their partnership under less-than-friendly terms.

That intrigued the hell out of me.

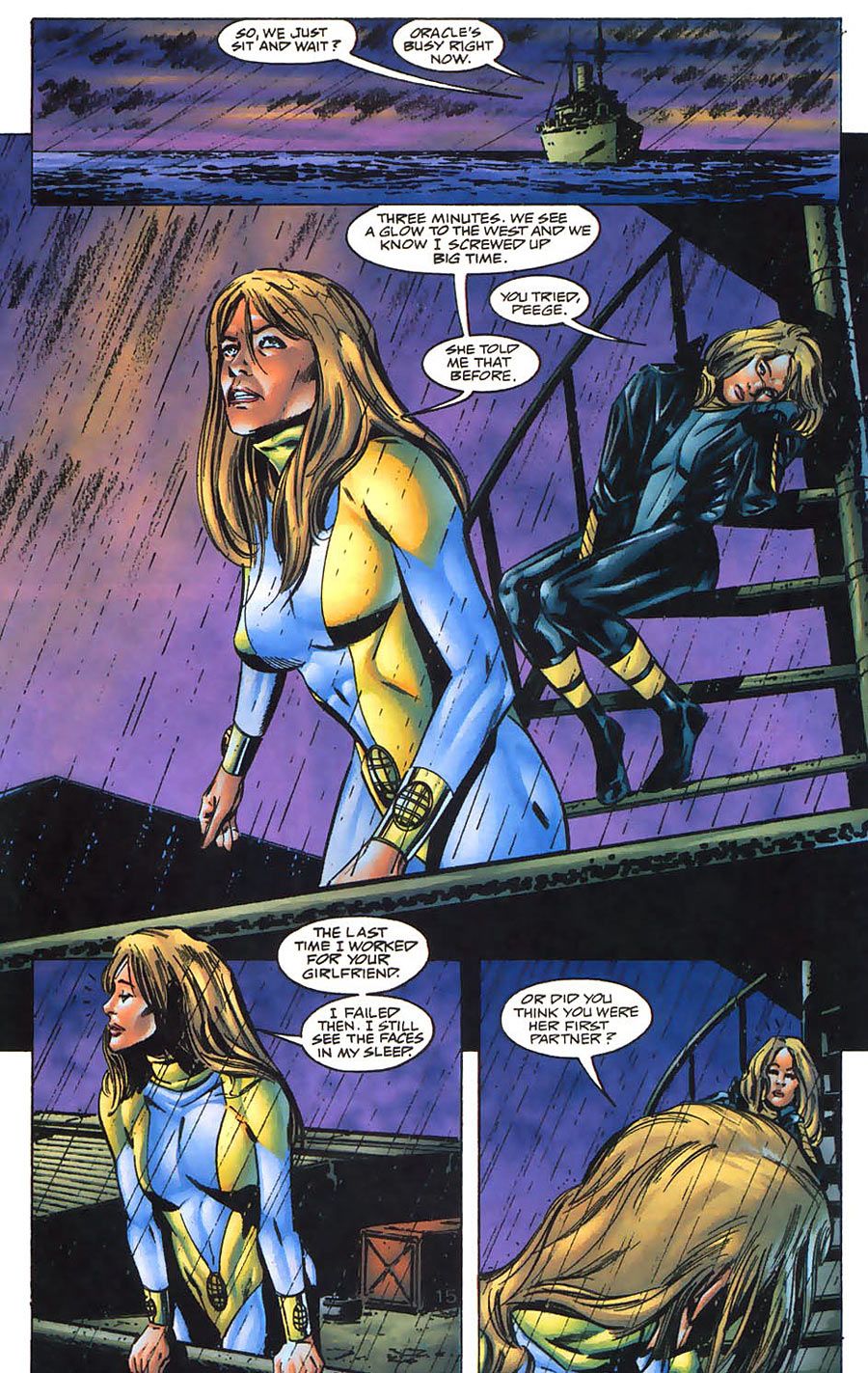

Power Girl made her first appearance in "Birds of Prey" during the series' first year. She was drawn by Patrick Zircher, whom I brought on board to co-illustrate two issues with Greg Land. Patrick provided a nice-looking version of Power Girl, but something wasn't right to me. A nagging in the back of my brain.

A few issues later, due to the revamp of the entire Batman line of books, Butch Guice started the series as the new artist. I was a fan of Butch's work for years, certainly during his "Superman" run, and I felt the maturity and feel of his art was what the series needed to take it to the next level.

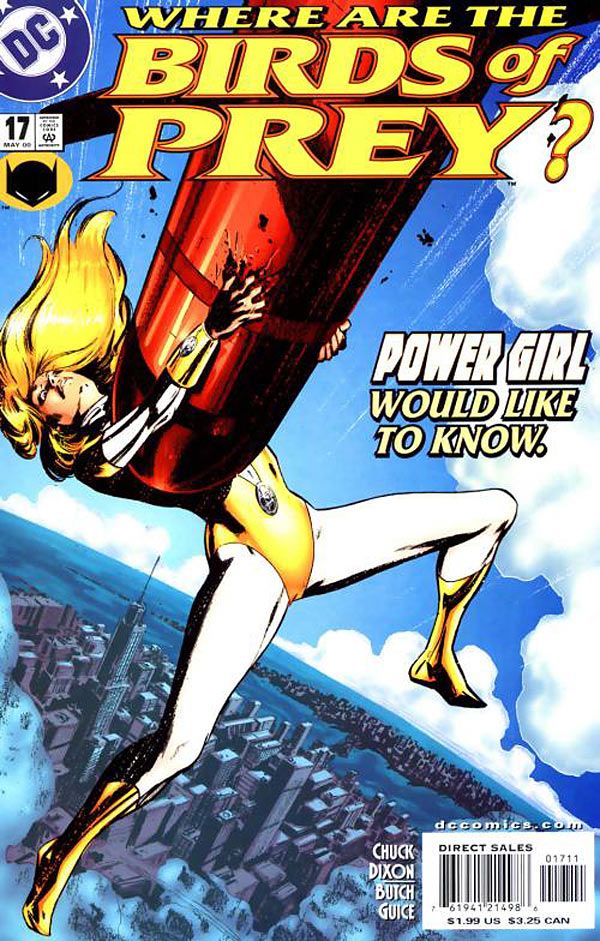

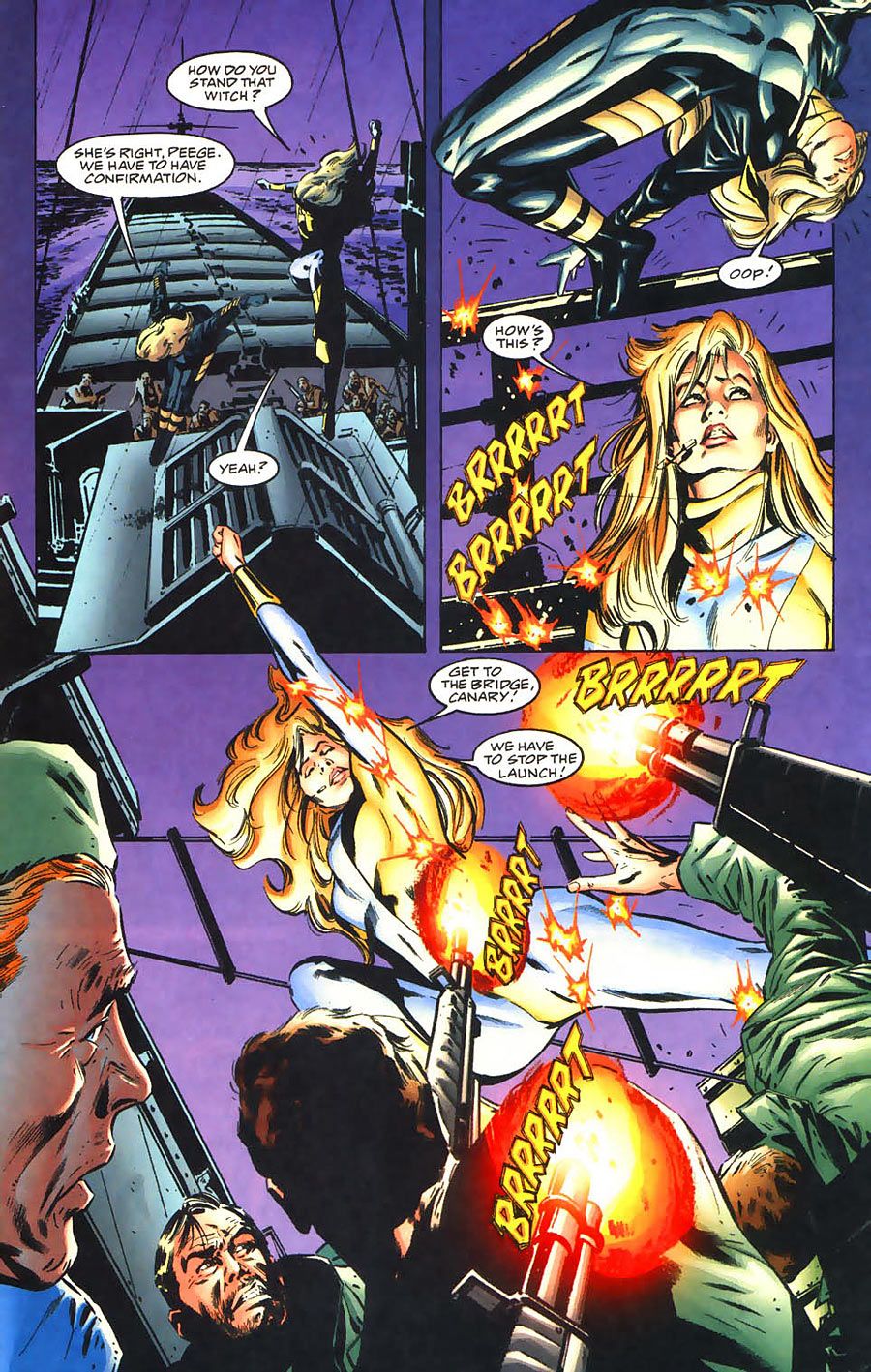

The first storyline of Butch's run involved The Joker's latest plan to engage in mass murder, culminating in the explosion of a nuclear warhead within New York City, and Oracle needed to call Power Girl back in out of the special missions cold to help her and Black Canary deal with the threat.

And it clicked for me. Power Girl did not look right to me in that outfit in this era of "Birds of Prey," which was a more grim title than in its first year.

Additionally, at the time (because this is superhero comics and the DC Universe gets revamped every ten or so years) because of the new continuity Power Girl was no longer related to Superman. She had Atlantean heritage, and came from a lineage of sorcery.

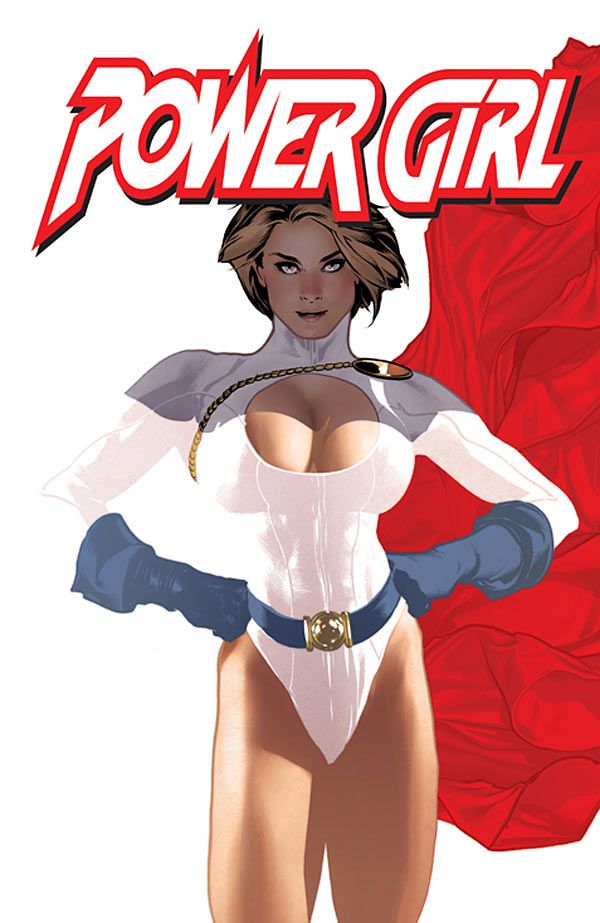

So I started to think of Power Girl from a cultural context. What would an Atlantean woman, a warrior of magic look like? I didn't think she's look like a knockoff Supergirl, that was for sure.

Digging back through my fanboy memory, I remembered that artist Bart Sears had designed a full-body costume for Power Girl while she was a member of the European contingent of The Justice League. It was a white and gold uniform.

That made more sense to me, for this majestic superpowered woman thrust into a techno-thriller world.

So after receiving permission from the "Aquaman" editor (all things Atlantis connect to Aquaman, after all), I had Butch update Power Girl's costume for the arc. Writer Chuck Dixon utilized the magic-based history to enhance his characterization of her, like good writers do.

Power Girl, in her revamped costume, came back into the DC Universe with a mild vengeance in "Birds of Prey" #16 and #17, and I felt good about it. In this book about female characterization and empowerment, the creative team and I did service to Power Girl.

Well, the Executive Editor of DC Comics at the time didn't think so, and we had a mild debate about it, ending in an impasse. He said my changing of the costume affected licensing. I said I asked permission to change it, and I had no regrets about it.

After I left DC Comics, a slow transformation went into effect over a number of comic books which ended in the return of Power Girl in her original outfit. I'm sure there were a number of fans who were thrilled, but again, I had no regrets.

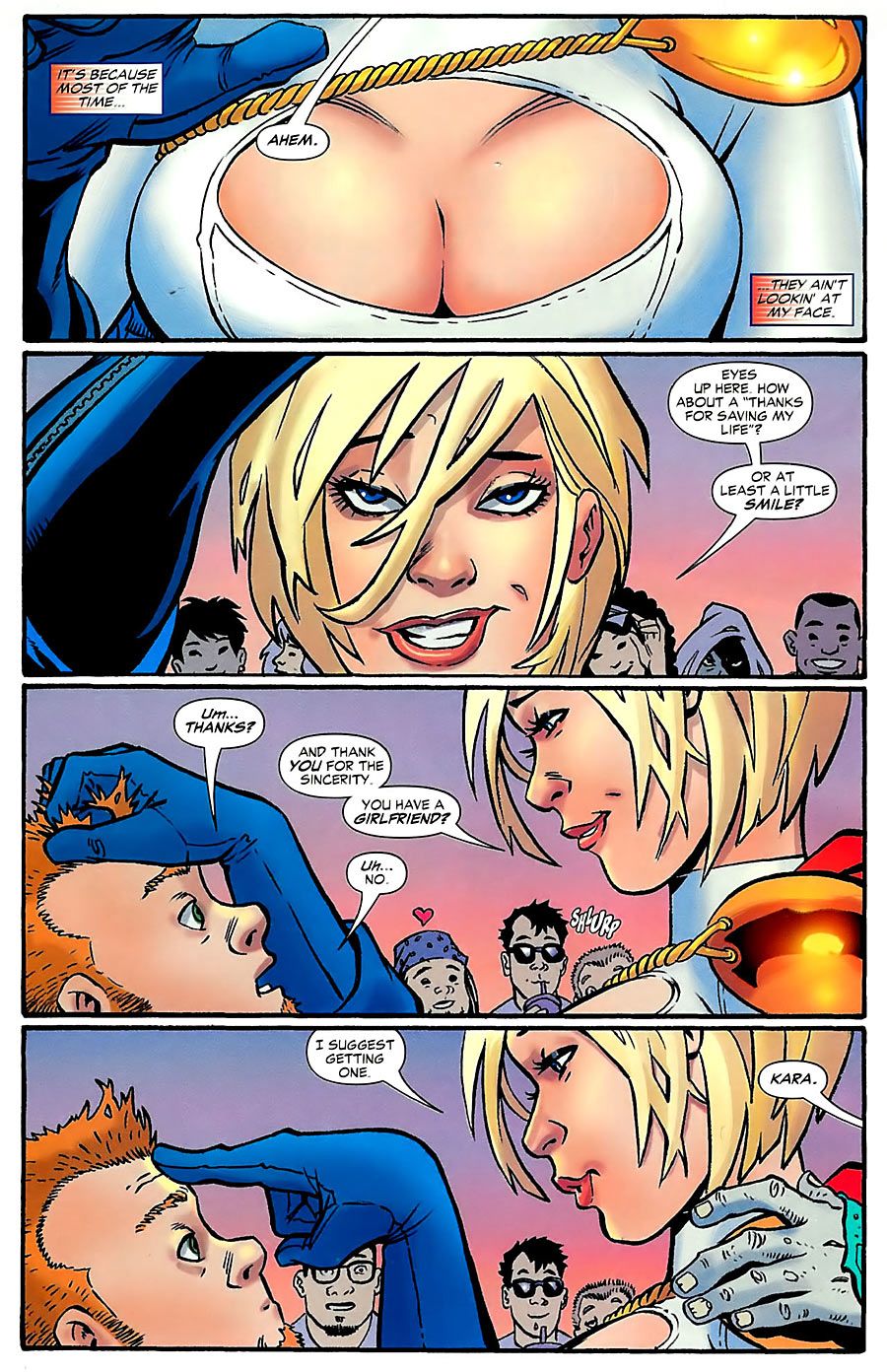

In the years that followed, Power Girl received her own series written by the prolific team of Justin Gray and "Harley Quinn" co-writer Jimmy Palmiotti and illustrated by "Harley Quinn" co-writer and artist Amanda Conner. They injected a sense of fun and light-heartedness into the book, at times using Power Girl's look as a source for comedic examination.

Years later, as the result of the DC Comics' time-bending, continuity-shattering, marketing juggernaut event called the "New 52," Power Girl received another costume revamp. This one was closer in some ways to her original outfit, without the big hole but with something on one of her breasts. Maybe a letter "P," maybe not. Also, it was a full-bodied costume, like she wore back in the day in my "Birds of Prey" run and in "Justice League Europe" before that.

Why did DC do that, I wonder? Remove the hole. Hmmm...

I'd like to think I was ahead of the curve, concerned about the visual portrayal of female characters before the fight for such things started building towards a fever pitch which possibly forced the various "vertical-thinking" parties within DC Comics to give the character a visual upgrade.

It was long overdue.

That said, I look at the iconic nature of Power Girl in the cosplay circles. As far as I've observed, Power Girl may be the most imitated DC Comics female character in back of Wonder Woman and Catwoman, and that's saying a lot.

Women have taken a visual created by a man and taken ownership of it.

And maybe that's the real power of Power Girl. Women from different walks of life and different body types dress up as this woman and go to conventions feeling good, feeling empowered in the way one does when they wear a costume of a hero, feeling understood with their choice and appreciated for it.

Do I think a grown woman with the name "Power Girl" is insulting and idiotic, and does nothing to improve the representation of women in comics?

Yes.

DC Comics may feel the same, because now there's a new Power Girl, and she's a girl... and she's Black, but that's another column, too.

Is the old visual of Power Girl, if I had a daughter or daughters, what I would want them to see as an iconic representation of a female superhero?

No, and there are many more options, anyway.

Power Girl is an interesting study in geek culture.

We may not be able to trace her changes along the changing zeitgeist the way we can with Wonder Woman. Some people may laugh at Power Girl, be offended by her, like her, or want to be her.

But she is deceptively complex in that there are many clashing opinions about her, and all of them may serve to be revelatory about the power fantasies of men and women, where our geek culture was, where it's going, and the miles it has yet to walk.

And as an epilogue, for all of my efforts to portray Power Girl in a way I considered respectful to the character, girls, and women in general, I made the mistake of approving a cover that had her catching a missile chest on... totally missing the underlying symbolism of the image.

This is me, shaking my head at my past self.

Joseph Phillip Illidge has been a public speaker on the subjects of race, comics, and politics at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Digital Book World's forum, Digitize Your Career: Marketing and Editing 2.0, Skidmore College, Purdue University, on the panel "Diversity in Comics: Race, Ethnicity, Gender and Sexual Orientation in American Comic Books," and at the Soho Gallery for Digital Art in New York City.

Joseph is the Head Writer for Verge Entertainment (www.verge.tv), a production company co-founded with Shawn Martinbrough, artist for the graphic novel series "Thief of Thieves" by "The Walking Dead" creator Robert Kirkman, and video game developer Milo Stone. Verge has developed an extensive library of intellectual properties for transmedia development. Live-action and animated television and film, video games, graphic novels, and web-based entertainment.

His latest project is "The Ren," a 200-page graphic novel about the romance between a young musician from the South and a Harlem-born dancer in 1925, set against the backdrop of a crime war and spotlighting the relationship between art and the underworld. "The Ren" will be published by First Second Books, a division of Macmillan.