For more than twenty years, Nate Powell has been creating comics and graphic novels including "Any Empire," "Swallow Me Whole," and "The Silence of Our Friends." During that time, he's received just about every prize a cartoonist can, including an Eisner Award and two Ignatz Awards. For the past few years, Powell has been collaborating with Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin on "March," an autobiographical memoir recounting Lewis' experiences as a civil rights leader, alongside Martin Luther King, Jr.

The first volume of the trilogy was a bestseller, was honored by the American Library Association, and became the first graphic novel to receive the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award.

Congressman Lewis, Andrew Aydin Revisit the Civil Rights Movement in "March"

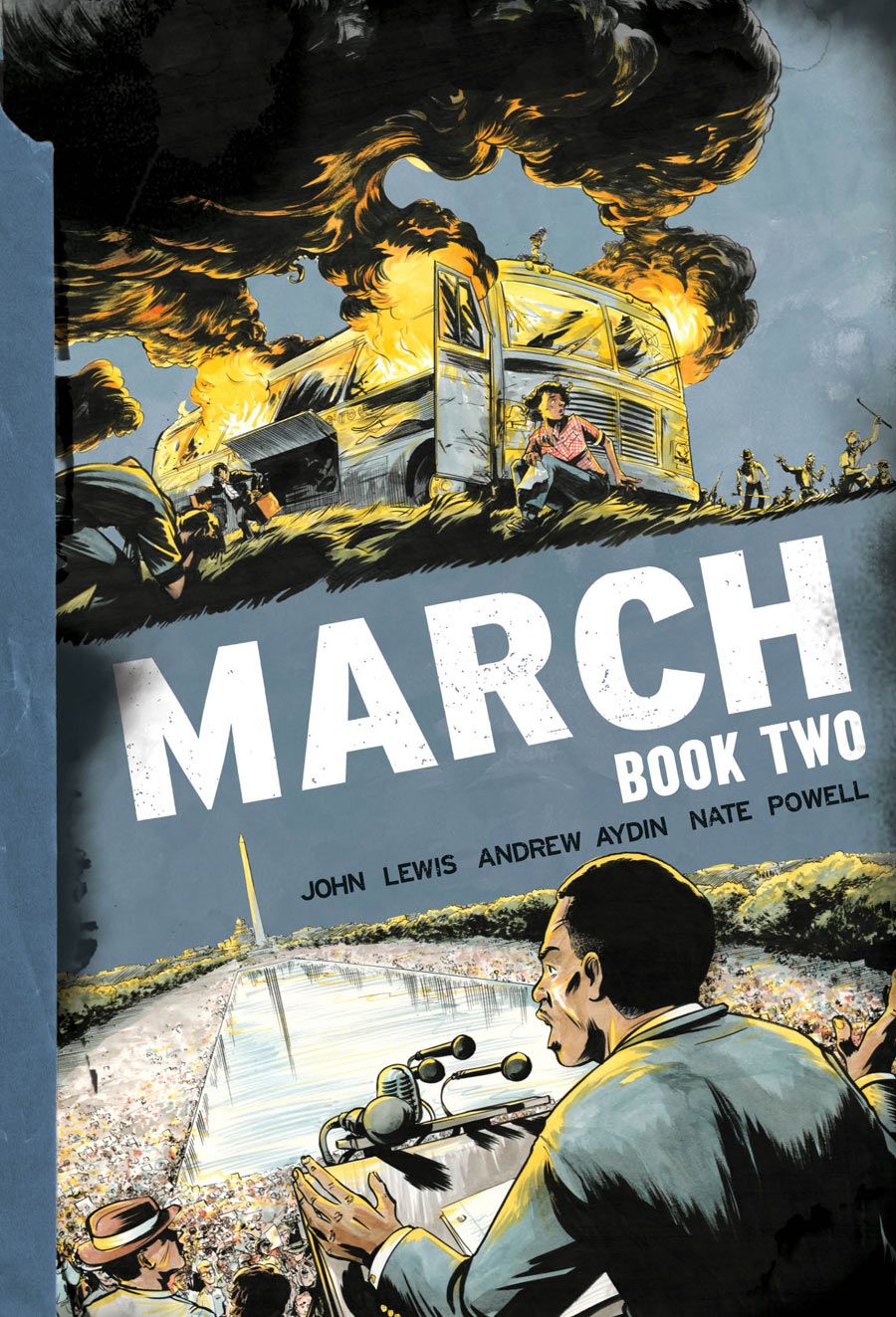

"March: Book Two," which was recently released by Top Shelf, is a much darker book than the first volume. While it depicts one of the high moments of the Movement, the 1963 March on Washington where Dr. King gave his famous "I Have a Dream" speech, it also shows what was happening before and afterwards, making it startlingly clear that while it was a great moment, it did not stop the brutal violence surrounding the movement. White supremacist groups, sometimes aided by law enforcement, fought desegregation and voting rights. There was assassination by sniper, bombing churches on Sunday mornings, and attacks on everyone involved, including children and the elderly. As Powell makes clear in our conversation, the specter of these events and those years are not neatly confined to the past.

CBR News: "March: Book Two" is a very different book from "Book One." I know that the original plan was to create a single volume, and then you guys decided to make it a trilogy. I'm curious about the conversation to turn it into three books and how you approached making them each feel like their own book.

Nate Powell: I'd say a lot of that emerged along the way. We made the decision to break it up into a trilogy at San Diego Comic Con in 2012. The original script that Andrew delivered to me was in many ways the same, but it was divided into six chapters. Once I broke down the script, I was like, "This is going to be at least twice as long as we think it's going to be." Instead of sitting around for five years, or however long it would take while I drew this thing, we were like, "Let's take some of the pressure off and divide it at its natural points."

Working together on "Book One" -- the three of us, plus Chris Staros and Leigh Walton -- we were able to work out a creative and editorial system of collaboration that's gotten more and more finely tuned. Andrew and Congressman Lewis and I learned a way of working together that grew and changed radically between the beginning and the end of "Book One." By the time we started "Book Two," we really had our creative system down. "Book Two" was a very different process than "Book One" by virtue of the time spent working.

It's easy to describe "Book Two" as a darker book, and it is. I mentioned to Andrew that in the minds of many people, "Book One" was what the Civil Rights Movement was like, when in reality it was much longer, much harder and much bloodier.

Oh, definitely. Andrew has a phrase that he uses when speaking about this that rings so true. We are taught -- and we tend to perpetuate this myth -- that the Civil Rights Movement was nine words long: "Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, I Have a Dream." I think what you're saying really backs up that notion. In terms of John Lewis' personal journey, "Book Two" is certainly a deepening of discovery and involvement. Not just a worldview broadening, but becoming much more personally aware of the counter-escalation to any progress that the Movement made.

"Book Two" is a very violent book. John Lewis and the Movement believed in nonviolence, but their opponents did not. There are bombings, snipers, beating, sicking dogs on children. Early on, I'm sure you had a conversation about how to depict violence and how much to depict.

That's an ongoing conversation. I think each situation presents a series of judgments. The way Congressman Lewis puts it is, "Make it plain." It's interesting coming from a comics background, because we've grown up reading comics with violence intrinsic to comics narratives -- especially growing up as kids of '70s/'80s/'90s mainstream comics. It's interesting because, not just as a creator but as a reader, "March" has really re-sensitized me to the representation of violence. All three of us have determined that the way it has to be done -- whether physical violence or hate speech -- is to show it plainly and unflinchingly. Basically if you present it as close to the human participants as possible -- both the perpetrators and victims -- it will do its own work as far as revealing the horror and the brutality of violence in any form.

Before working on "March," I've explored this relationship with violence in other books of mine, but just growing up as an American comic reader, there's a stylization of violence you're accustomed to. When it came time to do a lot of these scenes that you could term "action scenes," I found that I had to rely less on what I've learned through comics to convey the action, the drama, the horror and the darkness of a scene of violence, because the scene itself carries a completely different weight in the context of "March."

When you're depicting violence in "March," you do tend to stay close in and really focus on people's faces, even in wider scenes. Not only are you avoiding the stylization of violence we know, but you make it personal.

I aim for that in general. The Montgomery bus station scene, where it's like six or seven pages of fighting. It's easy to let that slip into a different kind of storytelling for violence. One that I do like a lot -- a Frank Miller or Geoff Darrow storytelling method that is further away, that uses more panels, that's more involved with repetition. It's beautiful in a storytelling way, but it serves a very different purpose.

Also, I try to pull the camera around so that occasionally the reader discovers that they are the person pulling the punch. I think the first time on the Freedom Rides, where they get attacked in South Carolina, somebody punches out John Lewis. It's a two-panel sequence of his face and then his face as he's receiving the punch, but the reader themselves is behind the camera delivering the punch. I'm trying to keep it interesting as a cartoonist, but I find, especially when you're reading about this white supremacist violence, it's important to keep the reader as uncomfortable as possible. I want to make the full context behind the violence apparent.

The first book ends on a hopeful, positive note, but it's a much darker story overall, raising the question of just how much progress they've made, ending with the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

I think the script originally had "Book Two" ending with the March on Washington, or perhaps with President Kennedy and the Big Six after the speech, but we were very mindful not to make it to seem like everything was fine. We were originally going to have "Book 3" open with the bombing, but if you're not aware of the history, the March on Washington happened just two and a half weeks before the bombing of the church. While we were writing and pencilling it, we imagined the white supremacists in Birmingham working on their bombing plans concurrent with the March on Washington. It seemed natural to end the book with the bombing itself to make the point that just because of this monumental occurrence, the March on Washington, it doesn't mean that a war of any sort had been won.

One big challenge for you is illustrating the March on Washington, which is one of the most depicted and known events of recent decades, and figuring out how portray Dr. King's speech.

Certainly. There were some really interesting things that we wanted to bring to light that are out there in the public record, or in Congressman Lewis' previous accounts like "Walking with the Wind," but are not illuminated enough. The entire controversy over the March. The last minute compromises over Lewis' speech. The fact that the Big Six didn't lead the march, though they'd planned to.

In terms of the weight carried by King's speech, there were a lot of considerations. We could've spent eighty pages on the march if we wanted to, but we were trying to make sure we were serving the function of the book and its overall focus. Some of those questions were answered for us because of limitations on King's words from the King estate. I can't remember if I made the suggestion or if it was Andrew, but we didn't necessarily need to include a direct excerpt from King's "I Have a Dream" speech. We have lines of that speech embedded in our bloodstream as Americans, and in my opinion, it served the strength of the narrative to stop time entirely during his speech and have a little bit of reflection that would tell the truth about his speech. I was always particularly moved by the fact that the "I have a dream" line itself was ad-libbed. Mahalia Jackson, the singer, was listening and she said, "Tell them about the dream, Martin," and he went for it. It was a dream that she had heard before. It was a mix of serving the function of the narrative of "March" and dealing with the fair-use limitations of King's words.

You depict Mahalia Jackson's line, and then we automatically hear the next line in our heads as you stop time and give the Congressman a chance to reflect and step back.

Certainly. It's also interesting because Congressman Lewis had heard Dr. King speak many, many times; he was, and is, John Lewis' hero. In "Walking with the Wind," he describes Dr. King's speech: "It was not, in my opinion, the best speech he ever gave. I think his speech four years later at the Riverside Church in New York, where he condemned the war in Vietnam and talked about the U.S. as 'the greatest purveyor of violence in the world' was by far the best speech of his life in terms of sheer tone and substance.'" Lewis did, however, say that "I Have a Dream" was "a masterpiece, truly immortal, he spoke his soul and anyone who saw it could feel it." We were trying to do the speech justice, and convey just how much of an impact it had on our society without further enamoring the speech itself with another layer of mythology.

I think that line speaks to Lewis' mindset then and now. He and the SNCC were much more interested in specific policy points, which is what Lewis' speech was concerned about, while King's speech is much more abstract. That speaks to their different roles in the movement.

Practically and generationally, for sure.

As far as "Book 3," have you figured out how it will work and where the book will end?

Yeah, we have the entire timeline and structure down. "Book 3" is going to end in 1965, around the passage of the Voting Rights Act. There is a lot of content that happens in '66-'68 that is part of "March," and is in the script, but at a certain point last year, we decided that the natural arc of the trilogy ends with the passage of the Voting Rights Act. We're currently hashing out whether the '66-'68 volume will be a fourth book (outside of the trilogy), or if it will serve as a very long epilogue in the omnibus edition. Most likely a fourth book.

The movie "Selma" came out recently, and I've heard and read many people saying -- in the most admiring way -- John Lewis was crazy back then.

[Laughs] Oh, yeah. An unwavering fellow. I finally saw it a couple days ago, and on the whole, I thought it was fantastic. It wrecked me for the rest of the day. It was also really enlightening and encouraging to see a different narrative take on the same events that we're covering. In one way, I've gotten very close to these events and their memory by serving as a tool for John Lewis' memories and experiences. It was also really necessary, I think, to watch the movie and be able to see those events literally outside of his perspective.

There's not really anything to spoil about the book, and even though it's a hard book to read at time, it really is an incredible work.

Thank you. We're all very happy with the way it turned out. As a team, we really clicked through the process of doing it. I don't know that I've ever had a collaboration work so well. It was a very fluid, organic, constantly honing it until the day we sent it off to the printer.

I'm sure that working on something as emotional as this, it's a very draining experience, and having that kind of close collaboration helps a lot.

For sure. A couple times a week, I'll get a reminder while drawing or researching of not just the sacrifices and the risks that so many people have made in this real life story, but also growing up as a white middle class Southerner, born in the seventies, how close I was to that time. Or to be more specific, how little had changed between 1985 and 1963 or '68. The more I research and read, I see how near-tangible the specter of these events, and of the Jim Crow South, was to me growing up in Montgomery, Alabama in the '80s. Just this week, I've been reading this book "Bloody Lowndes," about the Lowndes County Movement and the birth of what would serve as the impetus for the Oakland Black Panther Party. Reading it, I discovered that the secular private elementary school I went to in Montgomery was founded in 1955 as a white-flight response to Brown vs. Board of Education. There was a big lawsuit in the '70s by five African-Americans against it and another private school in town that shed light on their sketchy origins. I'm thirty-six years old now. I was going to that school thirty years after the desegregation order came down from the Supreme Court. Thirty years is a tangible thing, and it's not a long time. I understand what that is in real terms, now. It's haunting.

I don't want to end on such a heavy note, because I know that in addition to "March," there's another book collecting many of your short stories coming out in May.

Yes. I just wrapped up the corrections on that today. I'm really excited. I think that the stories work so well together as a body. In some ways, it's a "Sounds of Your Name Part 2" -- another decade's worth of work. It starts with the "Please Release" stories, in which I completely changed gears. It comes from a place of doing almost completely nonfiction essays then and slowly moving back into the word of weirdo fiction and horror. Around the time I finished "Swallow Me Whole," I started exploring through shorter stories a lot of issues with violence and power and racism in the American South that not only informed "Any Empire," but paved the way for me to be able to tackle "The Silence of Our Friends" and "March."

Right now you're busy preparing for your daughter's arrival, but you're also in the midst of a few other projects as well.

I just finished up a bunch of animated illustrations for a Southern Poverty Law Center documentary called "Selma: The Bridge To The Ballot." I don't think this is announced yet, but Van Jensen and I are working on a series for Dark Horse. We're in the early stages of working that up. Summer 2016 is coming up fast, so I'm getting to run with "March Book 3" because the next month is going to be time to start pencilling that. I need to wait until "Book 3" is done before I can really get back to work on my own graphic novels. I have another book called "Cover," which I've written and re-written, penciled and re-penciled on and off several times in the last few years. It's slowly brewing, and as soon as I get a minute, I'll be very happy to dive back into it.