At its core, Dana Simpson's comic strip "Phoebe and Her Unicorn" is exactly what the title promises -- a story about a little girl and her unicorn friend. But for Simpson, it's about much more.

Both Phoebe and Marigold the unicorn are representative of Simpson, albeit in different ways. Marigold is loosely Simpson's ego personified, while Phoebe is a physical representation of the cartoonist, representing who Simpson wanted to be in 1986.

"I always say, we use art to fill in the gaps, to get the things that we are denied by life. That's one of the reasons Phoebe exists," says Simpson, who transitioned from male to female in her twenties. "It's healing for me to have this child representation of myself who gets to be a little girl."

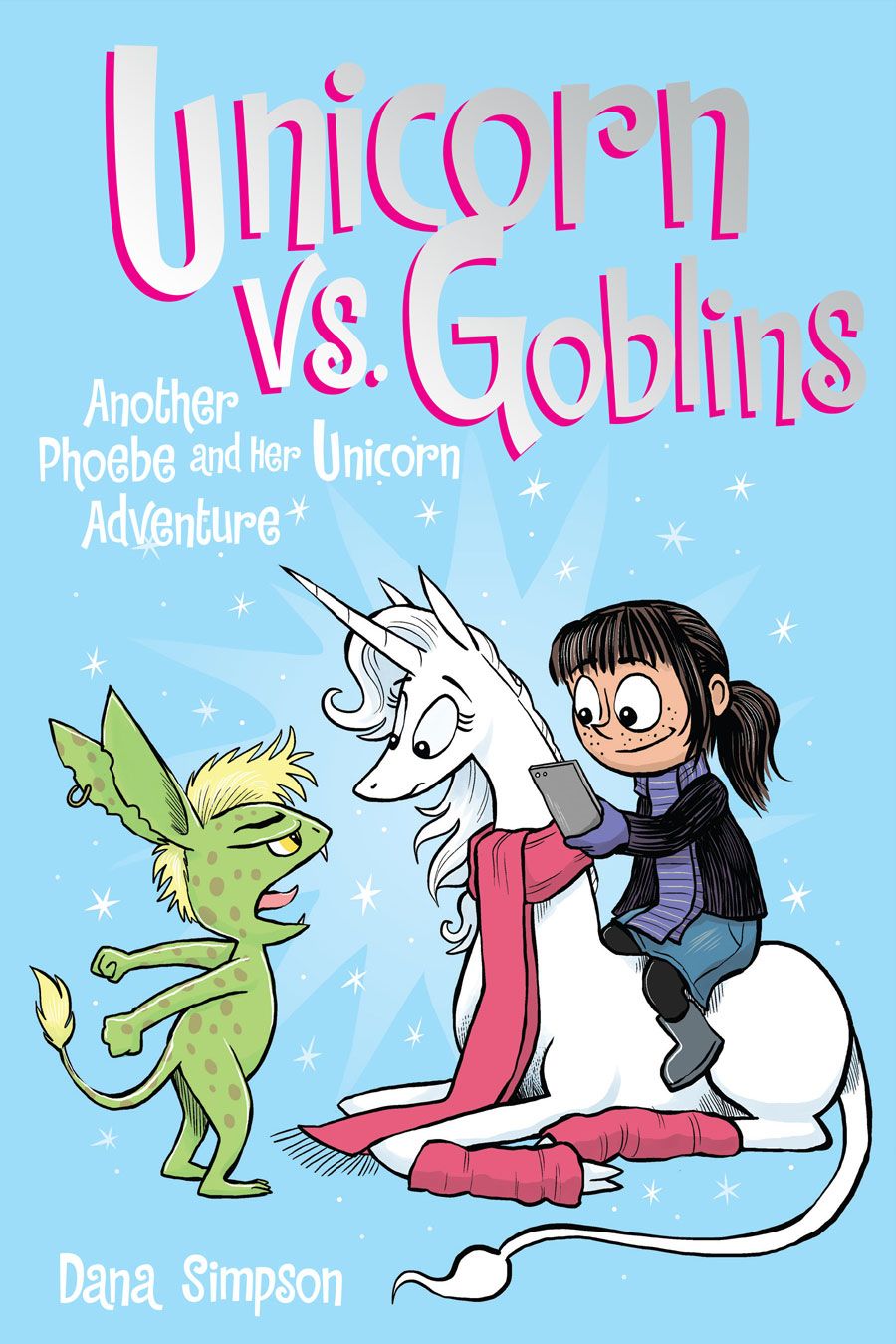

With her latest collection, "Unicorns vs Goblins: Another Phoebe and Her Unicorn Adventure," now on sale, Simpson dives deep in an in-depth conversation with CBR, discussing the relevance of the characters in her daily comic strip, the influence Peter S. Beagle's "The Last Unicorn" had on the creation of Marigold, and the "secret" origin of the strip's popular guest-stars, the goblins.

"Phoebe and Her Unicorn" is the result of you winning Amazon's Comic Strip Superstar in 2009, but for a strip called "Girl."

Dana Simpson: It starred a proto-Phoebe. Like Phoebe, she was a re-imagined child version of me, a little dark-haired girl running around in the woods. I grew up in Gig Harbor Washington where you walked out the back door and you're in the forest. The place is much more heavily developed now, but a lot of it was this idyllic, wild place when I was growing up. The original concept was she hangs out in the forest behind her house all the time, and she's friends with all these talking animals. I won with this 12-strip sample, and I thought that would be the strip -- you won, so just draw a bunch more of these and let's put them in the newspaper. In fact, there was a long development process, and partway through development, the unicorn showed up.

I was struggling to get the concept to work in a way that would please both me and my editors. John Glynn, who's the President of Universal now and he was my editor during development, said, "What you're handing in is better than some stuff that's currently syndicated but in this tight market, we need you to make something transcendent." He used the word transcendent. I was like, "Um, I'm not holding back transcendence." I was obligated under development to write and hand in thirty roughs every month. One day, I wrote one that had a unicorn in it. The girl had acquired the name Phoebe by then -- they told me you couldn't call a strip "Girl" because nobody would ever be able to Google it. I handed in the strip with the unicorn, but I already knew there was something there. It launched online about six months later -- she was the missing piece. I named the unicorn Marigold Heavenly Nostrils, after typing my name into an online unicorn name generator.

As you say, Phoebe is kind of you.

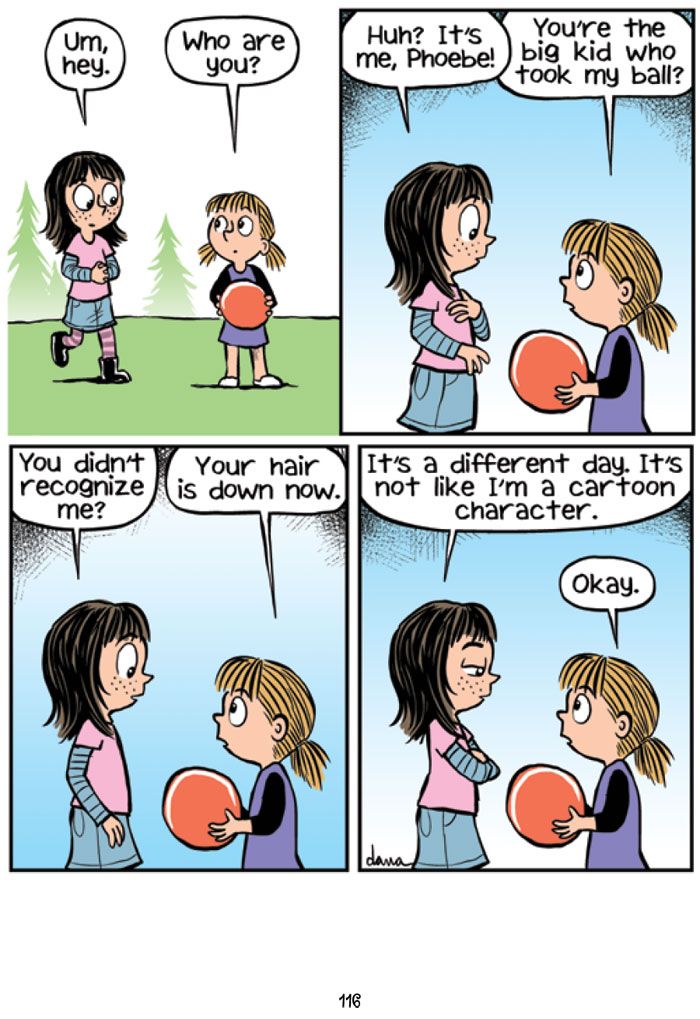

She is -- although Marigold is, too. Inevitably all the characters are sides of you. It was true of Ozy and Millie, and it's true of Phoebe and Marigold, too. It's a conversation going on in my head between two different areas of my personality. My inner child is talking to my -- I don't want to say Marigold is just my ego, but she is sort of unfiltered ego. That's part of her charm. Phoebe is self-consciously drawn to look like me. She has my freckles, she has my natural hair color, she has my round head and big eyes and a bit of my fashion sense. Charlie Brown was very much [Charles] Schulz, I think. I don't think it's uncommon to approach a character that way.

I think the twist in my case is that, as a transgender person, I did not get to be a little girl in real life in any literal way. I didn't have a bad childhood, but there was that missing piece. I didn't correct my gender until my twenties. Phoebe is 9, and I was 9 years old in 1986 and it was a really different world. I always say, we use art to fill in the gaps, to get the things that we are denied by life. That's one of the reasons Phoebe exists. It's healing for me to have this child representation of myself who gets to be a little girl -- and ride around on a unicorn.

There are all kinds of approaches to unicorns and how they look in literature and art. How did you figure out how Marigold would look and how she would act?

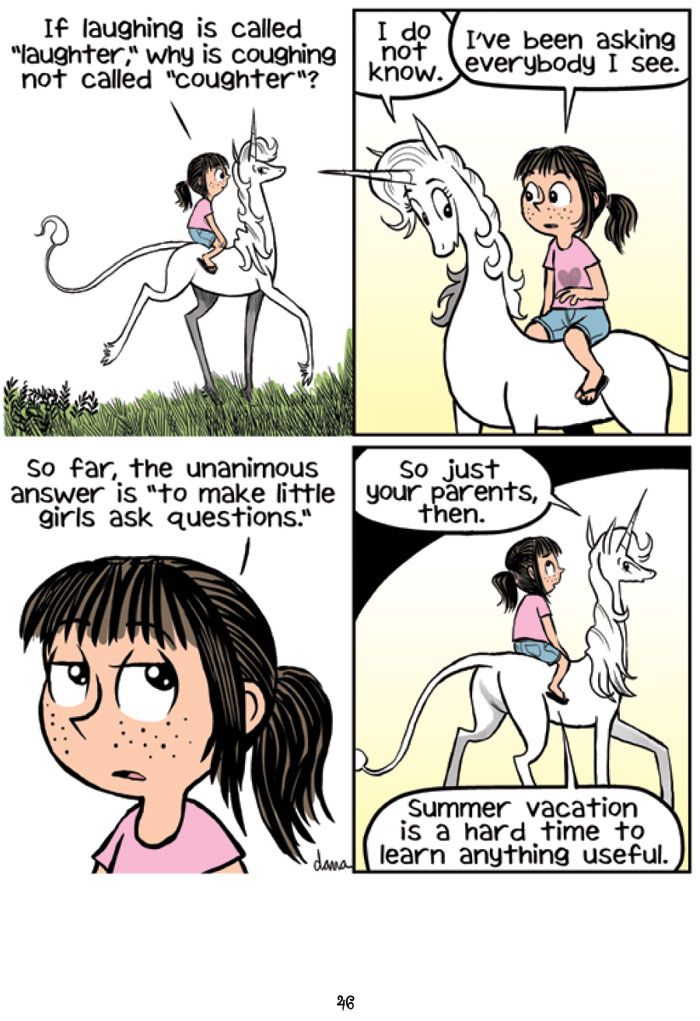

I ended up basing her pretty heavily on the idea of unicorns in the book/movie "The Last Unicorn" by Peter S. Beagle -- who, by the way, wrote the introduction to the first "Phoebe" book. I wanted her to be not just a horse with a horn, but mythical. She has cloven hooves and a lion tail and she's very willowy in her build. Deer-like more than horse-like. The first strip where we meet Marigold, she is staring at her reflection in a pond in the woods and Phoebe liberates her from that by hitting her on the head with a rock, accidentally. Early in the book, Peter describes unicorns as living in wood near reflective pools so that they can gaze at their own reflection because they know that they are the most beautiful and magical creatures in the world. I had a comedic take on that idea. That ended up being the basis for who Marigold is. She's not selfish in that she wants to take anything from anybody else, she just thinks she's amazing. This is common among unicorns in this universe. I would be lying if I said there wasn't also a bit of "My Little Pony" in there, too -- a healthy dose of Rarity and a sprinkling of Princess Celestia.

Lauren Faust writes about how Marigold acts in her introduction to your second book, and how the strip tries to redefine what we think of as feminine.

I love Lauren's introduction. She really went full feminist, which is great because that's what I admire about her work. She didn't use the word "feminist" when she talked about the strip, but that was what she was saying. I thought "My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic" was a remarkable feminist achievement in kids TV. In its original concept, the show was saying that there's no wrong way to be a girl. I deliberately set out to make something with two female personalities at the center of it. The strip wasn't going anywhere until I figured out I wanted to do that. The years that I was doing "Ozy and Millie," I was struggling with my own identity, and when I finally embraced that I'm actually a girl, that changed everything. That strip was a conversation between Millie, who was female, and Ozy, who was an androgynous boy. Nobody read it this way, and it wasn't consciously intended this way, but it was a conversation with myself about who I was and gender was a big part of that.

When I finally settled that question and I ended that strip and had to come up with another strip, I had to find another conversation to have with myself. Phoebe and Marigold are a conversation I'm having with myself in my own head, and when I realized both of those voices had to be female, that was when the strip started working. Now that the gender question is settled, I want to do a strip from this female point of view that I have embraced. I think it reads as feminist as it does, as girl positive as it does, partly because I made that decision. There are guys in the strip, but the main conversation has to be between two female voices. When Lauren wrote about how the strip represents a change in cultural perspective of who girls are, that we can now regard them as people, that is pretty much what I was going for. I didn't set out to make this grand feminist statement, but I think that's how representation is. You have to be able to see things through that character's eyes rather than guessing from the outside what they're going to do. That's why the strip reads the way that it does.

There are many aspects of the strip which read as feminine, but Faust points out how Marigold's vanity is seen and how it plays out.

She said vanity is a negative trait -- often ascribed specifically to women -- and Marigold turns that on its head. In his introduction, Peter S. Beagle called her a monster of ego, but Lauren has a different take. Marigold's ego doesn't come at the expense of anyone else. She doesn't run other people down. She just loves herself -- to a fault. And couldn't we all stand to love ourselves a little more?

Everyone else thinks she's the greatest.

Marigold tries not to fly in the face of public opinion. [Laughs]

You've gotten a lot of attention from the book world. You received a Pacific Northwest Book Award. You also received a Washington State Book Award -- not for comics, but for middle readers.

I almost feel like the strip and the books have different audiences. The audience that reads it as a strip skews older and the gender balance is more 50/50. People who are fans of the books don't necessarily have any concept that it's a strip. I have to explain to people that it's not a graphic novel, it's actually a collection of comic strips, and that surprises them. That audience skews younger, a lot more children. It's the same material, but packaged two different ways, it does reach two different audiences. With some overlap, of course.

Your strips typically feature more character based humor than setup, joke, punchline. Is that just how you think?

That seems to be what I'm good at writing. I'm not as good at abstract comedy as I am at character-based stuff. That's what tends to come out of me when I sit down to write. Every once in a while, I think of something that I think is really funny -- usually a visual, like Marigold roller skating, or Marigold wearing a bathing suit, swim fins and a snorkel. That will become a strip or series of strips because of the funny visual.

You do occasionally make longer story arcs, like the goblins story in the new book.

I'm under the advised restriction right now that stories shouldn't go over a week, and I tend to keep it to that. Since the newspaper launch, I try to keep stuff brief, and [my editor] is always telling me to make stuff even briefer. The storyline in the second book, where they're doing a school play, dragged on for six weeks. I say dragged on, because by the end I was like, I can barely remember what this strip was like before it was about this play. It was a good storyline and it had different parts. It wasn't just one thing for six weeks. I don't think I would want to do that now. I don't think I could do that now.

We're coming up on our one year anniversary in newspapers and still getting into new papers and finding new readers. I don't want to bury them in some long complicated story arc. When a strip starts in a newspaper, they run the introductory week. In the first book, there's the story of how they meet, that's three weeks, but for newspapers it's condensed into one week. My understanding is that newspapers run that week, and then they plunge into whatever I'm doing currently. It will be interesting when those strips start being in books. So far, everything in the books has been from the online run of the strip, and I think the longer storylines work well in book form. Maybe much better than if you ran them in newspapers. I'm interested in how readers will feel about that.

I did want to ask about the goblins and how they look. The cover to the new book really stands out.

They're sort of Muppet-y -- not like Kermit, but the weird Muppets that come out and eat other Muppets. They were actually designed largely by my sister Nicole, who is herself a really good artist. In many ways, I think Nikki is better than me. From a strictly technical standpoint, she grasps stuff intuitively that took me a long time to wrap my head around. I asked her to help me come up with a goblin design, and she nailed it. So credit where credit is due, my sister Nicole Johnson is responsible for how the goblins ended up looking. They're some of the most popular characters in the strip with long term readers, and the closest thing I've written to a catch phrase is "blart," which is what the goblins say. It doesn't have that many applications in day to day life.

You like doing these big, crazy stories every now and again.

I took a cue from "The Simpsons" Halloween episodes. There can be weirdness in the strip, but Halloween is a time to cut loose and have goblins running around kidnapping people. Anything can happen around Halloween.

Unicorns walking among us is just an everyday thing, after all.

Exactly. You only don't notice because of the shield of boringness.